Early YBA videos and their disobedient prehistory

by Michael Bracewell • May 2019 • Journal article

Disobedience, in the eyes of anyone who has read history, is man’s original virtue. It is through disobedience that progress has been made, through disobedience and through rebellion.1

1987

London. A sunny morning in late spring. Standing as though recently teleported to his present position, which is at the southern end of South Molton Street, is Stevo Pearce: founder of Some Bizzare Records, the intentionally misspelled label of choice for electro-futurists Soft Cell, Cabaret Voltaire and Depeche Mode; also psycho-dramatists The The, the new industrialist collective Test Dept. and their German equivalent, Einstürzende Neubauten.

Stevo looks managerial: somewhat portly, suited, with an air of pinstripe gangster. He appraises his location, where the tireless commerce of the West End gives way to what is then, still, the old-world opulence of Bond Street and Mayfair – the district of art dealers – as though he has indeed arrived from another planet, rather than from a first-floor office barely a mile away, halfway down New Cavendish Street.

The strange atmospherics of punk enabled Stevo to become a maverick and visionary impresario. His roots, his musical and ideological tastes, lie deep within the shadow side of post-punk creativity: febrile intensity and surreal psychology; the art of the seedy, needy, desperate, violent, voyeuristic, drug-guzzling, agonised, sexual, abject and politically angry. It is a mood and ideology defined by Soul Mining, the first album by The The, released in 1983, as much as it is by Soft Cell’s best-selling 1981 debut, Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret, featuring an NED Synclavier for the robot percussion and Cindy Ecstasy on backing vocals.

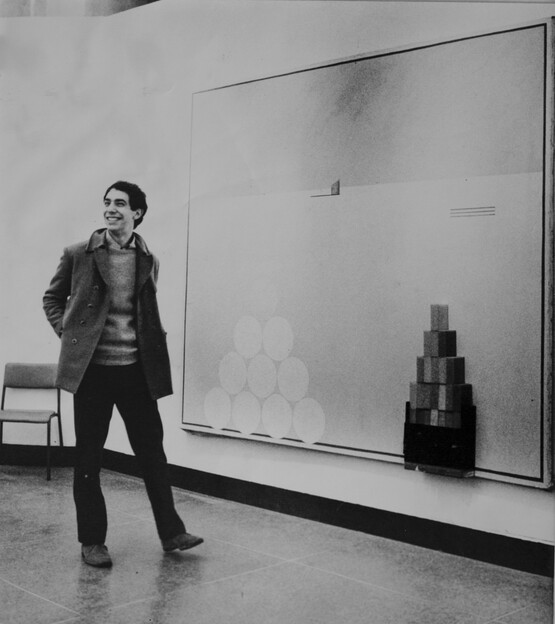

Hit records were made, money was made, and in 1987 Stevo – ahead of the curve – decided to open a gallery for contemporary art: Discreetly Bizzare, in a couple of rooms downstairs from his office. Fire eaters and Thai kick-boxers augmented its grand opening. Stevo, amiably enough, would subsequently pronounce, ‘I’m not a businessman; I’m an art terrorist’.2 Discreetly Bizzare exhibited visual art that mirrored the temper of the record label from which it had developed. Its selection of artists and the nature of the art it showed were inclined towards an outsider sensibility – often violent and grotesque – in sympathy with the vogue for the ‘abject’ and ‘transgressive’ that was prevalent within London’s avant-garde during the second half of the 1980s. Artists that showed there included Andy Dog (whose work appeared on sleeves for The The) FIG. 1; Val Denham (sleeves for Marc Almond and others) and the sculptor Malcolm Poynter.

Tom Baker, writing in The Face magazine, would pronounce:

Perhaps Stevo is set to be the Branson of the Nineties. Having made a reasonable amount of money out of Soft Cell and The The and probably very little money out of Test Dept and Psychic TV, the avant garde cheeky chappie has decided to get in on the art caper. Except that most of the artists who have shown at his gallery [. . .] seem to have at some time or other done record sleeves for one of his acts.3

While Stevo’s brave venture did not, ultimately, survive, it became an obscure but significant historical marker. It was, on the one hand, a premonition of the imminent rise to fashionability and economic power of contemporary visual art; on the other, an acknowledgment of the underground and sub-cultural avant-garde that emerged in the 1980s from punk and post-punk and historically preceded the rise and rise of ‘Young British Art’.

The art being made by this confluence of underground insiders and avant-garde outsiders was largely, if not completely, unfunded (vitally), consecrated to shock, confrontation and iconoclasm. It was apart yet parallel to the ‘art world’ proper, at once separatist and aloof. (It had no dialogue whatsoever, for example, with the then prominent ‘New Image Glasgow’ painters.)4 Rather, their art drew freely upon intellectual history, trash culture, weird science, the occult, ‘expérience limite’, politics, sexuality and queerness to reconfigure reality and demolish common assumptions. It was also profoundly romantic and loosely allied to the angst, activism and alienation of existential nihilism.

In September 1984, for instance, a celebration of the work of Georges Bataille, Violent Silence, was held at the Bloomsbury Theatre, London; it included Soft Cell co-founder Marc Almond (singing songs by Jacques Brel), members of Throbbing Gristle, readings by the writer and translator Paul Buck and a screening of Derek Jarman’s film (in Latin with English subtitles) Sebastiane (1976). Jarman himself was a crucial conduit, linking an old, Uranian gay socialist sensibility to the art school, King’s Road and Shad Thames bohemia of the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, and thence to the agents provocateurs of the post-punk temps modernes.

Some examples

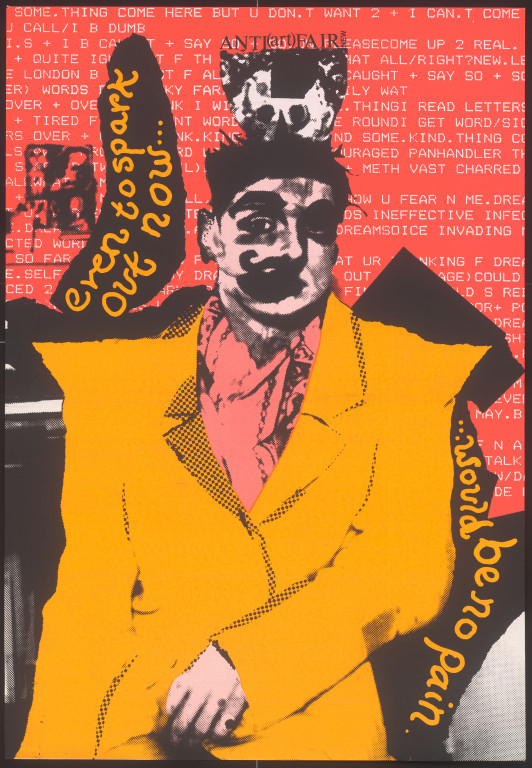

A book, Queens (1984) by a certain ‘Pickles’, a social anthropology of contemporary gay London (and as such a vividly Zola-esque portrait of the city) in various interconnecting literary forms; The Michael Clark Company at Riverside Studios, Hammersmith, blending classical ballet with glam rock and punk Dada FIG. 2; ‘Little Ghost’, a synth-pop track by Max, with videos by John Maybury and Akiko Hada; the ‘Anti-art’ group show organised by the art and rare-book dealer David Dawson in a disused Camden Town warehouse in 1986, with Day-Glo poster by Maybury and the artist Trojan, stating ‘Even to spark out now would be no pain’ FIG. 3.

The I.C.A. bookshop and Compendium Books in Camden High Street as literary descendants of the counter-culture: ideological embassies of imported critical theory, such as the journal Semiotext(e), and Latin American, postmodern-theoretical, psychoanalytical, Beat, Queer, ‘experimental’ punk-confrontational fiction; high priestess Kathy Acker, then resident in Hammersmith. The Fall. Peter Saville’s designs for Factory records FIG. 4; art in various media by Stephen Willats: Cha Cha Cha (1982; a book) and The Doppelganger (1984; a pair of prints); John Stezaker and Marc Camille Chaimowicz, then still isolated pulsars on the art world radar; ZG magazine – a publication for artists, writers and theorists to whom the ‘art world’ of the time seemed isolated and largely irrelevant; all night screenings at the Scala in Kings Cross and the Ritzy, Brixton; La Main Morte (1985) by Kenny Morris (ex-Siouxsie and The Banshees); Leigh Bowery as living sculpture at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery in October 1988; Neo Naturist messiness as protest art; yet more Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV; ‘Neoist’ projects (various) by polemicist-intellectual-troublemaker Stewart Home; the Mzui project at Waterloo Gallery in 1981 by Dome (Bruce Gilbert and Graham Lewis from Wire) with Russell Mills; Helen Chadwick’s sculpture in the medium of putrefaction, Carcass (1986); art-theorist-anarchist-duo Art in Ruins; Brian Eno as non-musician-artist-technician.

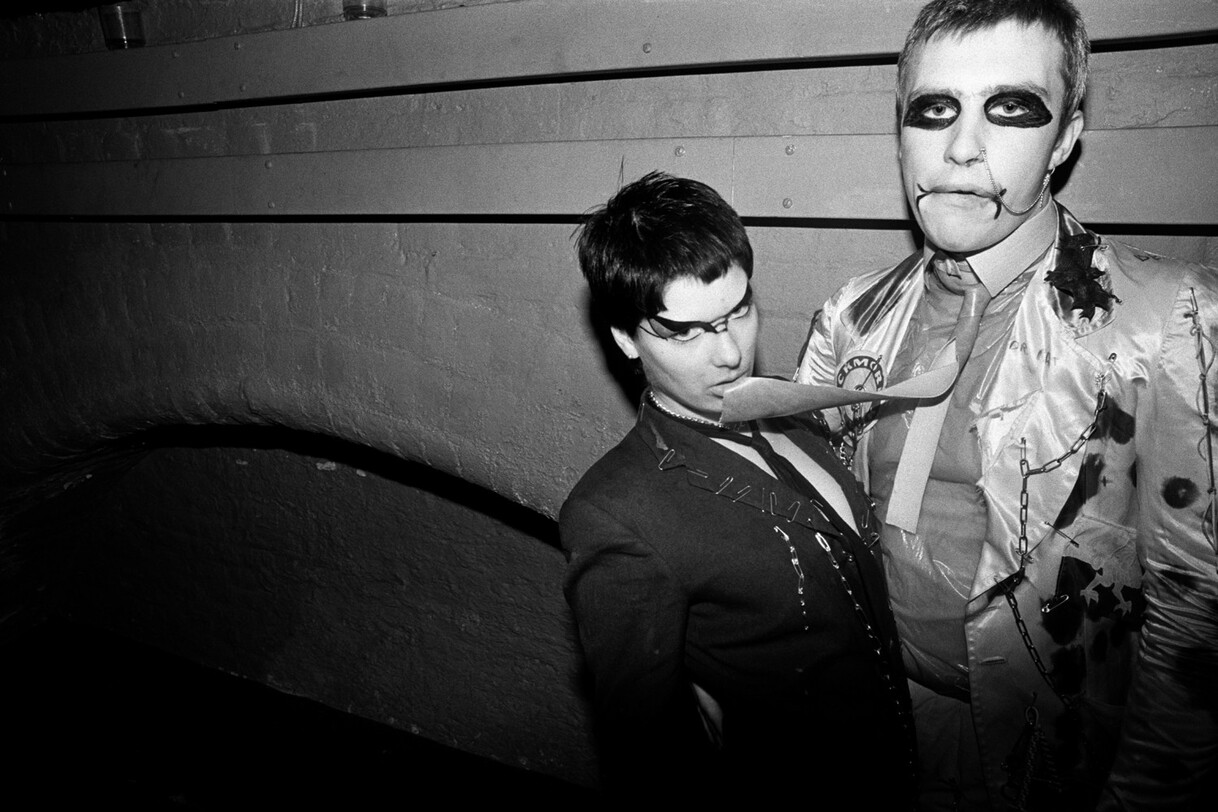

And Gilbert and George, now seeming like sleepless suited seers, psycho-surfing the vastness of the metropolis, the city toxic-fluorescent or monochrome, peopled by cute inscrutable male youths, sick moons and monstrous flowers, the whole depicted in dazzling clashes of bright poisonous colour; the arrival at Riverside Studios of a portentous lead sculpture, The High Priestess by forty-four-year-old Anselm Kiefer (1985–89; Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo), the work greeted as an emissary of German industrialism/trauma art; anarchist-interventionist film-makers The Grey Organisation (also collaborators with the indefatigable Psychic TV) in an organised overnight attack on 21st May 1985, splashing grey paint over the windows of what they called the ‘boring and lifeless’ galleries of Cork Street; Victor Burgin’s The Office at Night photowork pictures – more sci-fi greyness, yet redolent of Edward Hopper’s urban nocturnes; exhibitions in London by Bruce Nauman and Joseph Beuys; London punks FIG. 5 photographed c.1976–77 by Olivier Richon and Karen Knorr FIG. 6; and finally, right on cue, Warhol’s stark fright-wig final self-portraits, rolling the credits for the Death Disco.

And so on, all of these and more; post-structuralism’s equivalent to the list of guests who came to Gatsby’s party, combining to create a short-lived post-punk-art-as-sub-cultural-lifestyle art world, which seemed at the time more an evolved form of the pop and rock music sensibility.

Meanwhile, in the contemporary art world proper, its new imperial phase, the BritLondon explosion is close at hand but not quite arrived. Or even expected. Baker’s assessment of rumours of a visual arts renaissance (suffixing his unimpressed review of Discreetly Bizzare in The Face) was telling in this regard: ‘There is in fact supposed to be a gallery renaissance at the moment’, he reported, ‘But I don’t see how a load of revamped antique shops in Portobello selling polite paintings and gimmicky sculptures to first-time home buyers constitutes a renaissance’.5

In its engagement with contemporary art – however bizarre – Stevo’s venture formalised an aspect of post-punk sub-culture’s fragmentation into many different forms with many different affiliations, from the political – the notion of a Thatcherism-provoked English civil war – to post-punk as a postmodern reclamation of Dada or the Ballets Russes. In any case, its spaces provided an open venue for sharp-toothed status-blurring enquiries into art, music and everything in between; an underground precursor to the world of the YBAs, as penniless and outcast as its nimble successor was showered with fame and patrician gold.

1993

Their backs to the bottle-stacked bar, in a pub somewhere, are two clowns, one taller than the other. They are dressed in full traditional regalia – face paint, false nose, crazy hair, baggy trousers, bowler hat, outsized painted mouths like black bananas – but they smoke and drink like a pair of old caretakers FIG. 7. They look seedy. It is perhaps the middle of the afternoon. These clowns might be off duty, discussing life, workmates down-the-pub; hard-nosed bastard descendants of Archie Rice.

They look like imposters. It is hard to know where the gag begins and ends, in conceptual terms; but the gag (the honking bicycle horn, the drink, the fags, the behavioural embellishments of the scene) is nihilistic and drawn out: a set of sickening yet compelling narratives, conversationally recounted by the two extravagantly attired clowns: horror stories told as though from the mouths of adolescents.

As Oscar Wilde noted, ‘Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth’.6 These clowns, with their painted smiles and Batman villain demeanours, recount to one another absurd, quotidian stories of unimaginable violence, gorging on the bizarre, stomach-turning gore. The charnel house; blood and guts; the scene of the accident. They try to out-do one another, as though to see who might sicken first, or who remains unperturbed, coolly implacable and ready for more.

One clown seems evil, the other fate’s stooge – something out of Samuel Beckett, indeed (‘to find a form to accommodate the mess – that is the task of the artist now’);7 such are these two jokers – Angus Fairhurst and Damien Hirst, young artists who migrated to London from Kent and Leeds respectively, the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of the darkened underpass; and this funny, stupid, nasty conversation, this collision of circus clowning and horror death stories, is their art: A couple of cannibals eating a clown (I should Coco).

Why are they doing this? And why do they seem so present, clear, assured, their every word and gesture incisive, memorable, strange – so delighting in their unpleasantness – so defined?

The Wildean ‘disobedience’ that enabled artistic and psychological progress included that form of patricide which does away with the immediately preceding authority and order. It does this with all the callous brutality of youth, laughing as it topples the statues, desecrates hitherto sacred beliefs and mocks as hopelessly outdated, absurd and irrelevant all that does not aid the invention and triumph of its new order. And there is truth in the cruelty of such disobedience – the same truth that makes Fairhurst’s and Hirst’s outrageous update of Nauman’s clowns, Beckett’s stranded outcasts and comic-book villains so pulverising and compelling in its plain daft laddishness. Their film consolidates and advances a century-long history of artistic ‘disobedience’, from the flippant, dandified and insolent brilliance of Wilde, to the street urchin sneer and hit-and-run speed of the Sex Pistols.

1846

Karl Kraus described the nineteenth century fin-de-siècle, the end of the old civilisation of Europe, as ‘the last days of the end of the world’ – a poetic phrase that sounds as suited to science fiction as to the fading light of a last imperial summer.8 What to do, during the last days of the end of the world? We might learn from Søren Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, written pseudonymously as Johannes Climacus in 1846:

It is now about four years ago that I got the notion of wanting to try my luck as an author. I remember it quite clearly; it was on a Sunday, yes, that’s it, a Sunday afternoon. I was seated as usual, out-of-doors at the café in the Frederiksberg Garden [. . .] I had been a student for half a score of years. Although never lazy, all my activity nevertheless was like a glittering inactivity, a kind of occupation for which I still have a great partiality, and for which perhaps I even have a little genius.9

The term ‘glittering inactivity’ is arresting. A paradox: evocative yet precise, signifying an ironic conflation of grand gesture and fatuousness, fine-mindedness and uncurious, easeful indolence – the existential boredom of the privileged, even talented, ‘superfluous man’ of Russian fiction.

Climacus, however, proposes to redress his own ‘glittering inactivity’ (in the face of advancing age) with a mission as poised as it is perverse: noting his lack of achievements, Climacus first ponders ‘the precious and much heralded men’ who are the spiritual benefactors of the age and who ‘know how to benefit mankind by making life easier and easier’. From this consideration comes his revelation, in the form of a double paradox:

Here my soliloquy was interrupted, for my cigar was smoked out and a new one had to be lit. So I smoked again, and then suddenly this thought flashed through my mind: ‘You must do something, but inasmuch as with your limited capacities it will be impossible to make anything easier than it has become, you must, with the same humanitarian enthusiasm as the others, undertake to make something harder’. This notion pleased me immensely [. . .] Out of love for mankind, and out of despair at my embarrassing situation, seeing that I had accomplished nothing and was unable to make anything easier than it had already been made, and moved by a genuine interest in those who make everything easy, I conceived it as my task to create difficulties everywhere.

There is beauty in the simplicity of this mission. And perhaps, as a statement from the Aesthetic self – in the last days of the end of the world (which, oddly, are always with us) – Climacus’s revelation stands as an intriguing definition of the artist’s calling: 'I conceived it as my task to create difficulties everywhere'.

Climacus’s vow can be seen as a corrective to a destructive or stultifying surfeit of ease. The ‘creator of difficulties’ as a metaphor for the artist, whose task is to constantly renew the acts of looking and seeing, and to introduce disobedience – to make a raid on predictability, deploy the odd, the shocking and the unexpected, disrupt perceptual complacencies and translate, through art, personal truth into universal truth.

The artistic qualities ascribed to the Victorian fin-de-siècle – a febrile, morbid decadence, heavy with dream-laden symbolism, sexual insinuation and overwrought aesthetic extravagance – describe an opulent world approaching either implosion or catastrophe. The deaths of Wilde and John Ruskin in 1900 – the former disgraced, the latter mentally ill – mark the end of an epoch and a line of aesthetic enquiry. London, New York and the great European capitals then entered the ‘last days of the end of the world’ denoted by Kraus and described in the early, war-shadowed writings of T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

1976

There is a reflection of this history, in London especially, in the ‘fin-de-millennium’ years of the twentieth century, between the late 1970s and mid 1990s. By 1976 one version of modernity (the pre-digital version, in fact) appears exhausted: socially, financially, culturally and even materially. The old post-war modernity has become the landscape of punk: a derelict shot at the future, of failing Brutalism, dark subways, rotting bedsits and corrugated iron fencing, from Hammersmith to Covent Garden.

The punk movement in 1976–77 had described the experience of living in a modern world that felt like a derelict future. Punk became a catalyst of the militant and contrary creativity independent of and oppositional to the institutions of the art world. When punk’s first manifestation came quickly to an end, its short-lived blaze of violence was replaced between 1978 and 1981 by an atmosphere of requiem, elegy, anxiety and existential enquiry.

Coinciding with the election of Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister in 1979, economics and politics entered a volatile state of flux. New technology began to enable new financial markets. In London, business ethos and luxury consumerism began to flourish. Within the sub-cultural avant-garde that had developed from punk, the oppositional and confrontational tendency devolved from the ‘art world’ proper to explore aggressively politicised artistic positions. As demonstrated by the prevailing ethos at Some Bizzare Records, these resembled simultaneously updates of nineteenth-century decadence – neurosis, the abject and transgression – and the iconoclasm of Dada, as revived by Stevo, The Grey Organisation, Psychic TV and others as ‘art terrorism’. Such ‘creation of difficulties’, as ever, was a reflexive corrective to what its perpetrators regarded as social, cultural and artistic stagnation.

In April 1986 Amstrad electronics purchased from Sinclair Research the worldwide rights to sell and manufacture their computer products – the success of which would lead to the launch of Amstrad’s market-leading PC1512 computer and be a starting whistle for the digital age. This rise to pre-eminence of computers would coincide with the popular use of the term ‘postmodernism’ as cultural shorthand to describe a new experience of society and culture. Appropriation, collage, irony, historicism, intention and authorship became open to experimental and audacious uses. During this same period – the mid-1980s – the institutions and establishment of British contemporary art had remained either aloof, unaware or remote from the potent mood of change that had shaped and inspired sub-cultural creativity. This discrepancy was due to differing experiences and expectations of purpose, context, discourse, perception and speed.

By the early 1990s, a small group of young British artists realised their need to make a break from the past and reinvent, for themselves, the meaning and purpose of art. Their method would be one of clever disobedience. Rejecting dominant academic and critical theoretical approaches, they made early works on film and video that were primal, personal, aphoristic and existential. These works were made on little or no budget, before the artists achieved fame. They are also, vitally, the products of a London that no longer exists – they were made in the strange, fin-de-siècle half-light, part dawn of a new epoch (the digital) and part dusk of the last days of the end of the old world.

With Wildean ambition, these films were like calling cards for the artists who made them. Several are based around a personal experience of music. Others involve abject comedy routines. They remind the viewer that absurd or surreal comedy is the nearest thing that the British have ever possessed to a national avant-garde, from the Sitwells onwards. A line in ‘God Save the Queen’ by The Sex Pistols expresses this: ‘God save your mad parade’. At the same time, all have echoes of Beckett: ‘You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on’.10

Each are radical declarations of identity, image, creativity, autonomy and newness, at a time when Britain was undergoing fundamental technological, political, social and economic changes, the consequences of which are still being played out. Reprising Matthew Arnold, the viewer’s aim in these works remains ‘to see the object as in itself it really is’.11 But how? By experiencing the presence of each individual work of art, its gravitational field; to feel what each does, as itself, beyond cleverness, unencumbered by projections of context and meaning; free from history’s tightening grip to be nothing but itself.

1993–95

The melancholy of an English seaside town FIG. 8: a shot at happiness, long fallen wide; a boxed jigsaw gradually fading in the window of a closed sweetshop. The sand-gold sunshine, the sky that turns a deeper shade of blue as the day moves slowly to dusk, a quickening breeze and the exhilarations – real, imagined or recalled – of evening. Why do these seaside towns, as though sedated with sunsets, seem to suggest endings? The end of day, the end of summer, the end of youth, the end of living? The last light lingers like a low minor chord.

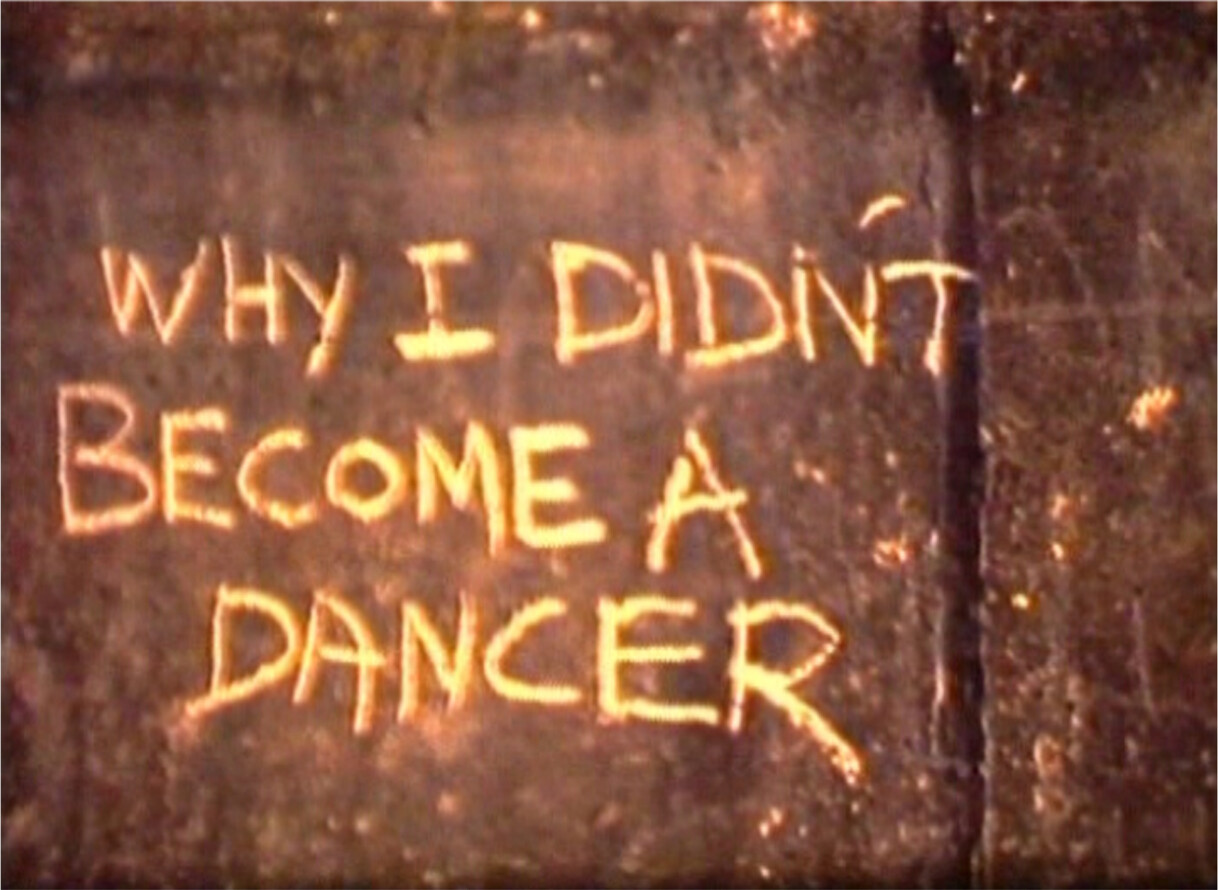

And here in the watery colours of a picture postcard, like a home video from the past, are concrete-coloured cliffs, the tide blackened under the lip of a sea wall. Chalked in comic-strip capital letters, a title – ‘Why I didn’t become a dancer’ FIG. 9 – and the name of this film’s author and its date, ‘Tracey Emin, 1995’.12The scene changes; the image begins momentarily to judder and shake; it seems that whoever is holding the camera is running, out of breath. We see the shuddering image of a featureless building that appears to date from the 1950s – a secondary school.

What sounds like a young or teenaged woman’s voice (we presume it must be Emin's) begins to speak over further homemade footage of this seaside town, which we soon learn is Margate – a long-established, then coarsened and fading holiday resort on the Kent coast. Her tone becomes a significant aspect of the film: the Thames Estuary twang, despondent, resigned, briefly warm – ‘the summer was amazing’ – then accusatory, resentful. It is the tone of dashed hope, abjection and finally of triumph. Over shots of the town – cafes, pubs, clubs, amusement arcades, lawns, seagulls, novelties – Emin tells an autobiographical tale of early adolescence, beginning with how she dropped out of school at the age of thirteen.

She relates how she discovered first the town itself; then casual sex with many different, mostly older men, and then dancing – through which she fantasised (in 1978, the summer of the disco craze) that she might escape the confines of Margate to discover success and fulfilment in London. She dances at a local competition – ‘the big one’, she says – which might deliver this triumph; but as she dances, a group of men (most of whom, she comments, she had had sex with at some time or other) begin to clap loudly and chant ‘slag’. Distressed, she is no longer able to hear the music; disorientated and traumatised, she runs off the dance floor, down to the beach and in a moment of epiphany realises that she has just outgrown the small-town world which has hitherto been her universe and the arena of her rites of passage.

Slipping into the present tense, Emin sardonically and vehemently dedicates the closing minutes of the film to some of the young men (whom she addresses directly, by their Christian names) who had mocked and insulted her at the dance competition. The film then cuts to Emin dancing happily and energetically to a disco track in an empty white studio FIG. 10. She is wearing (in the dance party street style of the 1990s) a loose shirt, cut-off denim shorts and laced-up workmen’s boots.

‘Seediness’, wrote Graham Greene in 1935, ‘has a very deep appeal [. . .] it seems to satisfy, temporarily, the sense of nostalgia for something lost’.13 English seaside towns, which have become the very Versailles of seediness, might satiate even the keenest sense of nostalgia with a sense of something lost. Time, place and atmosphere are entwined in Emin’s autobiographical narrative: the seaside town joining with her legion of abusive former lovers to endorse a personal loss of her own; a loss of innocence, perhaps.

These losses in turn become the forge in which her independence and ambition, as proposed at least by the closing minutes of the film, were shaped and sharpened. The Super 8 tale of underage sex, humiliation and escape is presented raw, at once knowing and heroic; perhaps even a little disingenuous in its public catharsis: the parading of the personal, sordid-sentimental, suffering and victimhood, predictive of times to come.

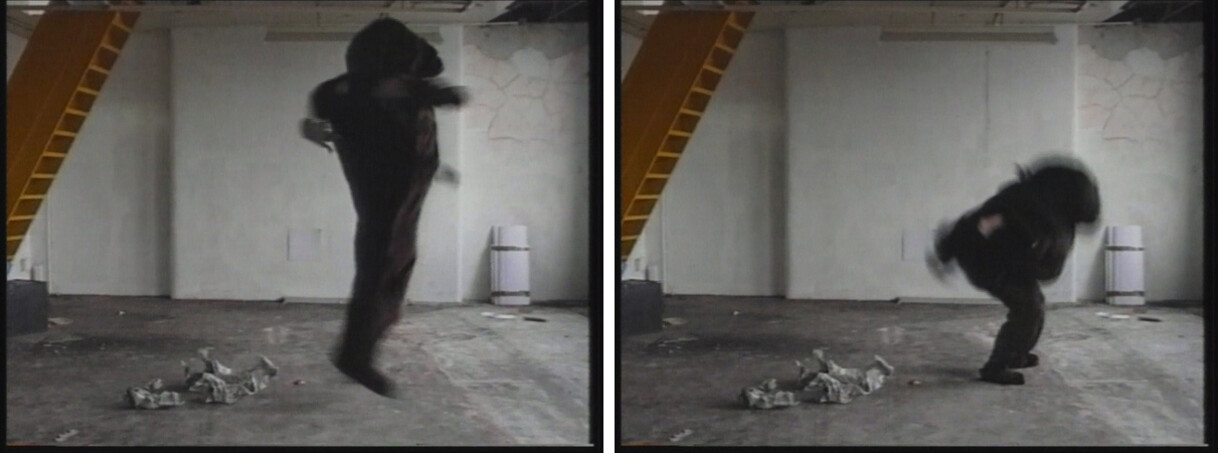

A colour video made the same year by Angus Fairhurst, Cheap and Ill-Fitting Gorilla Suit, depicts the artist in an empty shabby and utilitarian room FIG. 11. Less seedy than vacated. The plasterwork is cracking to the right of the chimney breast; what one presumes is the profile of a flight of wooden steps can be seen rising sharply on the left. The concrete floor looks gritty and dirty. There seems to be daylight coming from an unseen window on the right, but the light is mean, flat. Everything about the space and its atmosphere seems transient, dim, grimy, industrial, impersonal.

We see a figure (we assume Fairhurst himself) dressed in the ‘cheap and ill-fitting gorilla suit’ of the title. For a few seconds, the gorilla-suited figure stands in semi-profile. The picture quality is murky, the sound echoing and indistinct. As with Emin’s film, the ‘amateur’ quality of the film becomes a significant feature of its visual language. After a few seconds, the gorilla-suited figure starts to jump energetically up and down, flailing his arms.

As he does so, the rustling and rasping sound of the newspaper padding with which the suit is stuffed becomes louder. He continues to jump, rhythmically but frantically, occasionally off-balance. The suit begins to disintegrate at the seams, and the newspaper padding – loosely crushed sheets – spews out of the suit and on to the floor. As they fall, the man continues to jump, now on top of these balls of newspaper. At one point he stumbles off camera, and a woman’s voice – indistinct – seems to tell him to move back into the centre of the space. He does so, continuing to jump and flail, and as the suit falls apart, he appears to slough it like a skin and is revealed naked underneath. Once the last remnants of the suit have fallen away, he walks out of shot to the viewer’s left, his body thin and white.

These pre-fame but myth-building DIY short films by the later-labelled Young British Artists have an air of existential rituals, actions in the medium of self-debasement, purification ceremonies in dingy non-spaces in east or south London: a means of beginning.

Gary Hume’s short film Me as King Cnut comprises a static shot of the artist, wearing a shapeless diamond-patterned pullover, a pair of jeans and a gold cardboard crown from the Burger King fast-food chain. He is seated in an old bath that stands in what look like an old light-industrial yard. The bath is being continuously filled with water from a hose threaded through one of the empty tap sockets: a comic, garden-centre-like squirt of water; and thus the bath is constantly overflowing.

The drab urban-suburban setting, the landscape of cheap studio space, informs the work – let’s do the show right here; a venerable tradition, now bringing to mind an older London. A male voice (more assisting friend than director) asks off camera: ‘What’s the story again?’ as a small boy walks into shot with a packet of cigarettes, one of which the crowned artist takes and lights. As he does so, and as the overflowing old bath continues to splash onto the cemented yard, he begins to tell the legend of King Cnut, whose attempt to hold back the tide can be seen as both an allegory of wisdom (demonstrating to his court that even a king has no power over nature) and an allegory of foolish pride. With the crown pushed down low over his forehead, his thick brown hair escaping out from underneath, Hume’s visage is almost medieval. Or that of a workman gone mad. It is difficult not to consider that ‘Cnut’ is an anagram of ‘cunt’ – lowest slang, smelling of lager lout; and yet this sits at odds with the rather elegant (albeit comically so) conceit of the piece. The cardboard crown, alone, seems a device passed on – from Hugo Ball or Ubu Roi, perhaps – transformative.

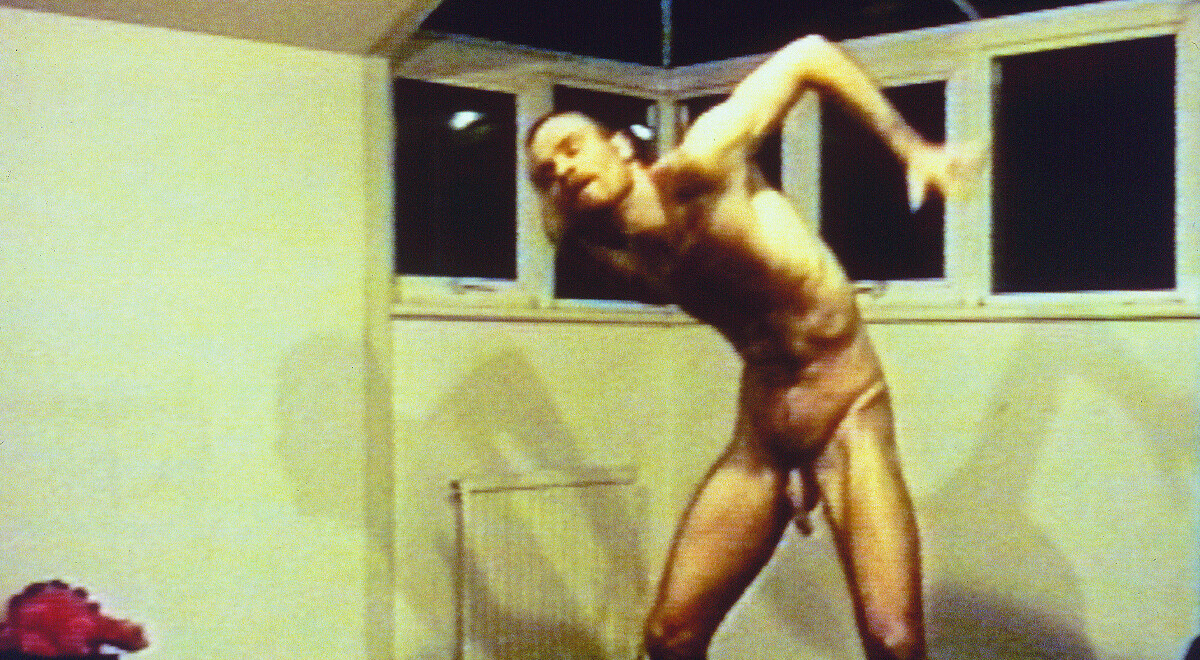

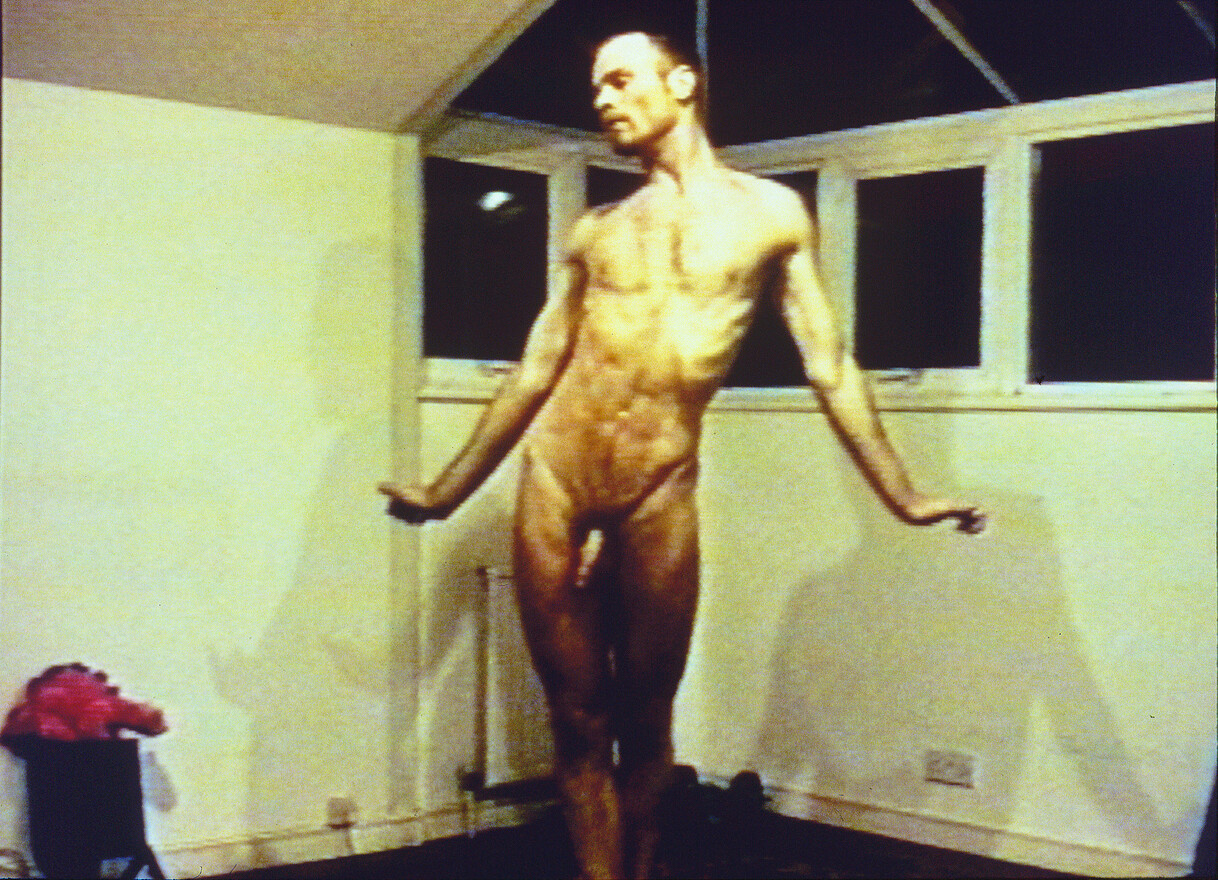

Sam Taylor-Johnson’s ten-minute video Brontosaurus (1994) is, by contrast, warmly lit with golden light. The timbre of the film, however, is just as coarse and technically rudimentary as those by Emin, Fairhurst and Hume FIG. 12. The space looks domestic, makeshift – the corner of a top-floor room in a new-build block of flats, with a line of windows at waist height and a section of glass roof. A bright pink toy dinosaur stands on what looks like a small black speaker; there is a dumb-bell in one corner.

But the space seems confined – too confined, at any rate, for the naked, athletic, lightly bearded young man who dances within it in slow motion. His head is shaved down to stubble; his body is muscular and sinewy FIG. 13. The soundtrack to his slowed-down dance is a richly romantic, plangent piece of classical music: the strings seem to both pierce the heart and tug at it, melancholic and full of grandeur. The dancing man always faces in the same direction throughout; filmed diagonally from the side, he gyrates his pelvis, raises and lifts his arms and head, absorbed in the music. The hint of gravitas is either enhanced or undermined by his exposed, flailing genitals; letting it all hang out. The viewer intuits that the young man is hearing different music to the soundtrack we can hear. His eyes close or look upwards as though in ecstatic trance. The film goes to black at the point the (audible, classical) soundtrack ends, the young man thus vanishing in mid-dance, even as a few seconds earlier he has struck near-pirouette-like attitudes.

Another home video and another banal location: this time a glass-roofed shopping mall. A sunny working day, to judge from the other pedestrians, shoppers and squares of bright sunlight on the precinct floor. The shopping arcade – a branch of the electrical goods store Currys is visible on the right-hand-side of the scene – might date from the 1980s; there are hints of postmodern vernacular in the fanlight hemisphere of glass at the far end, the crypto-Parisian white globe lamps, the probably synthetic greenery.

Here, in Gillian Wearing’s work Dancing In Peckham (1994) FIG. 14 a young woman, dressed in flared trousers and a densely patterned, short-sleeved shirt worn over a white T-shirt is energetically dancing – apparently in silence. She goes for it, coming up with all kinds of moves. Her dancing is loose-limbed, absorbed; at times floatingly psychedelic, at others more lithe and sexual, occasionally almost twisting, sometimes miming a sleeping gesture, then rocking out, then just jigging about. Like the young man in Brontosaurus, like Emin not becoming a dancer, she appears deeply involved in her own private soundtrack, ecstatically in the hold of her music. As she dances, her shoulder-length black hair flails in the square of sunshine, and nobody passing by seems to take much notice.

All made between 1993 and 1995, these six film and video works by Young British Artists appear to have more than their moving-image medium – a technology made recently affordable by mass production for the domestic market – in common. The three films by women (Emin, Taylor-Johnson, Wearing) take dancing as their central motif (and who’s to say that Fairhurst isn’t dancing in his cheap and ill-fitting gorilla suit?) and in each the dancing is used to explore identity and alienation. In Brontosaurus and Dancing in Peckham the viewer does not hear the dancer’s music; both depict a discrepancy between appearance and reality, between inner and outer worlds. In Why I Never Became a Dancer, the artist relates how she was driven off the dance floor by the chants of young men – abuse to which she later responds by dancing in the safer space of her London studio, joyously free of them, forever, existentially released.

As declarations of a new generational order – a postmodern renaissance – these works are determinedly primal and vernacular. Rooted in modern urban experience and redolent of adolescent or young adult partying, they are basic: a house-share youthful experience of London; affiliated to music culture and a love of music that for artists who had grown up during the legendary years of pop and rock music’s artistic and social power would be every bit as influential, if not more so, as the history of art. And they declare themselves in a manner requiring no particular skill and no budget, at once ancient and modern: by dancing and clowning around.

Hirst, Fairhurst and Hume thus propose a kind of slapstick absurdist, Anglicised ‘Ubu Roi’ mode of farceur. Their worlds recall those of surreal British comedy: a postmodern update of the Goons, Monty Python, Spike Milligan, Gurney Slade or the Bonzo Dog Dooh-Dah Band – the urban or suburban common man, embroiled in Dada, offset and heightened by drab, mundane surroundings.

These comic performances appear intimate with anxiety and unease, frustration and breakdown. Above all, these film and video works seem to convey the desire and the need to break out, break away and declare a new freedom; jumping and flailing and moving with physical violence, forcing a Year Zero, wiping the slate clean of all that went before while wearing the mask of Comedy. In their different ways, each of these young artists use masks – of inarticulacy, incompetence or insolence – and farce as an alibi for their existential strategies of ‘becoming’.

In the lineage of punk, these films celebrate frustration – histrionics, sex and humiliation, including ‘taking the piss’ or self-ridicule – by making use of friends, cheap technology and public or industrial spaces. And in their different ways these films articulate artistic and emotional claustrophobia. As with first-wave punk, frustration is converted into disobedience, audacity, contrariness, insolence and the absurdism of the mad parade; into energy and raw, edgy pronouncement, with an incisiveness that feels as freshly minted as a pristine machine part. There is wit too, and constant reference to irony – all in keeping with the creation of difficulties as artistic strategy.

A Cheap and Ill-Fitting Gorilla Suit seems the most deeply felt – raw, troubled, stark. But all six, having youth on their imperial side – newly capable of moving faster than the rest of us, than any other form – appeared to have brought a quality of inestimable importance to the making of art: minds wholly in tune with their times.

The films discussed in this article will be presented in the exhibition NEW ORDER at Sprüth Magers, London (23rd July–14th September 2019), which also includes work made between 1976 and 1995 by Peter Saville, Richard Hamilton, Karen Knorr and Olivier Richon.