Early YBA videos and their disobedient prehistory

by Michael Bracewell • Journal article

by Matthew Cheale

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 12.01.2022

In May 1992 Derek Jarman (1942–94), aged fifty, drove to Manchester, where the City Art Gallery bore a huge banner that proclaimed: ‘Queer – Derek Jarman’ FIG.1. Signalling the exhibition of Jarman’s paintings therein, the banner was, as the artist recounted, ‘surely a world first for civic gay pride’.1 In this liberating atmosphere, Jarman began a series of new paintings: frenetic smears, thick impasto, newspaper pasted on canvas and macabre titles. When they were shown a year later in Manchester they made his name as a painter. It is therefore apt that the current Jarman retrospective, which was originally presented at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (IMMA), in 2019, and comprises works produced over four decades, is held at the Manchester Art Gallery. Delayed for a year by the pandemic, it arrives as the AIDS epidemic reaches its fortieth anniversary. The exhibition eschews Jarman’s writing, instead foregrounding his career as a painter whose broad influences frequently seem contradictory – from ancient English landscapes to flat, hard-edged Minimalism.

Jarman made an extraordinary entry into the art world in 1967: he was included in the prestigious Young Contemporaries (now New Contemporaries) exhibition at Tate Gallery, London, for which one of his paintings won the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation Prize for Landscape FIG.2. Then aged twenty-five, he had assessed the London art scene around him precisely – dominated as it was by New Generation Sculpture and American modernism as supported by Clement Greenberg – and shifted his attention towards the flatbed picture plane and everyday motifs championed by Leo Steinberg. At times, his means were simple (a set square stuck to canvas), while at others they were more complex (a pyramid of brightly coloured sponges affixed to canvas, mirrored in a pyramid of painted circles). In this way Jarman reintroduced the readymade into painting – taps, a towel rail, a toothbrush holder – all were rendered not only useless, but also homeless. Like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol a few years later, whose borrowings from everyday life inserted banality into modernist painting, Jarman at this time can be seen as a transitional figure between Pop art and Conceptual art.

For Jarman, precision was as important as the commonplace. He suggested a shift from painting as a pictorial field with ‘eye-tricking imagery: Trompe l’œil water, real taps, classical statues’ to a perfectly balanced composition in which forms are flattened and simplified: ‘There are no longer any figures or objects, and definitely no jokes’.2 A trio of landscapes from 1967–72 FIG.3 is influenced by Giorgio de Chirico, who Jarman quotes in the first of his autobiographical journals, Dancing Ledge. In contrast to De Chirico’s favoured classical quaysides and scenes bathed in shadow or sun, Jarman's canvases are metrically precise compositions in which linear planes shift in compressed geometries; the colours are muted and grubby and lines flicker here and there. Another landscape from 1972 depicts angular rocks, a brown striped beach and a stormy sky with two overlapping pole-like bands of colour. The work is striking in its simplicity – so spare, in fact, that it verges on pure abstraction.

These landscapes hint at Jarman’s travels of the time: a summer in sleepy Seaview on the Isle of Wight, with days spent drawing the chalky cliffs, fossil hunting and driving around the island with his mother, Betts. They also show his influences, from Marcel Duchamp and El Lissitzky to David Hockney, De Chirico and Pop art. In his biography of the artist, Tony Peake describes him, at the end of 1968, riffling through the exhibition catalogue for The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), where many of these artists appeared.3 At the time Jarman supported himself by working on Ballet for Small Spaces FIG.4 and Sir John Gielgud’s Don Giovanni at Sadler’s Wells, crafting sets with geometric shapes, obelisks, cones, squares and circles.

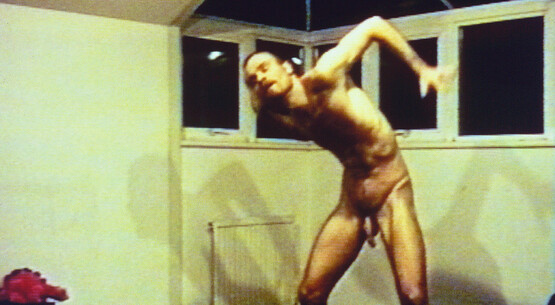

In 1982 Jarman travelled to Florence, and it was here that he hit his stride as a figurative painter. ‘Caravaggio deeply affected these paintings’, Jarman noted later that year, referring to his so-called ‘black paintings’ for the Edward Totah Gallery, London, many of which are on display in this retrospective, each a different peregrination of the figure.4 The reclining man in Irresistible Grace (1982) appears as the emblematic dead Christ of the pietà, most notably recalling Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ (1603–04; Vatican Museums). Jarman had been incorporating religious and sexual iconography, the male nude and physical marble fragments into his work since 1975, but following his travels in Italy, he also introduced gold leaf into the surfaces of his paintings. A year later, other more contemporary references abound: The Archer (1983), for example, is based on a 1950s homoerotic photograph from Physique Pictorial magazine.

The first rooms of the exhibition show something of Jarman’s early work, with his theatre designs clustered halfway through. It is not until the final rooms that we encounter Jarman’s deep engagement with protest. In 1986 Jarman spoke of his HIV diagnosis as causing him to feel ‘pushed into yet another corner’.5 This suggests a desire for activism – political as well as artistic – that goes beyond temperament and the heated ideologies of the period. And Jarman did intensify his subjects along with his gestures; the title of a large painting, Infection FIG.5, is violently inscribed into its surface. This intimate testimony and evidence may well align with other public disclosures, including ‘outing’, by film-makers, actors and other artists around this time. ‘My paintings are social realism’, Jarman wrote, ‘they show the collision between the unreality of the popular press and the state of mind of someone with AIDS’.6 In 1992, along with inscribed words, Jarman introduced tabloid headlines into his work in order to push against this division between personal and public narratives: ‘I painted these pictures fast and loose [. . .] through the popular press’ (p.216). As with the introduction of readymades to painting, we can credit this strategy to Rauschenberg who assimilated print media into his works. Adding paint to newspaper, as demonstrated in Morphine FIG.6, may seem like a simple action, but it too is more complicated than it looks: ‘My friends were lost, they died in these headlines’.7 In Morphine, Jarman takes aim at the tabloid war on homosexuality, incorporating front pages of the Star, which are dominated by the word ‘FILTH’ in reference to a ‘rent boy’ storyline in Eastenders. Similarly, his inscribed marks in Infection expose the by-lines beneath the thick impasto. For Jarman, then, the newspaper operates as both evidence of procedure and traces of evidence.

The curators of the exhibition under review claim that Jarman’s ‘art was barely divisible from his life’ (p.143), and his painting is boundless in autobiographical allusions: primarily referencing his illness, medication and pain, as well as his time spent at Prospect Cottage, Dungeness. Jarman once admitted ‘the artist must abrogate his mystery’ and described painting as a form of self-defence.8 Hockney, Jarman wrote, ‘had a sure grasp of publicity’ and, like Warhol, turned the artist into ‘an absolute icon’, a trope that Jarman reinforced in his own example as queer ‘saint’ and AIDS activist.9 How then to explain his influence on the practice of painting beyond his activism? Dotted with used condoms, pills and religious iconography, his late assemblages are more morbid than marching in spirit. Sometimes his work evokes the coffin as well as the crucifix, as in I.N.R.I FIG.7. On the other hand, Jarman treated his painting with melancholic humour. A note from 1992 reads: ‘I painted these pictures with no hope and wild laughter’.10 Two of his largest paintings, titled Death and Dizzy Bitch (both 1993), are hung adjacently in the last room. With the frenetic smears of concentric circles that mark the former like a shooting target, à la Johns or the frantic slashes across the bright red expanse of the latter, these paintings convey the gravity of the frail, disoriented body. Even when Jarman smeared ‘Queer’ across the shape of a heart, the radicality of the gesture did appear to be recouped. That is the power of Jarman’s painting: he was able to signify absence and loss while producing marks that seem more alive than dead. He imbued painting with the radicality that could only be ascribed to protest.