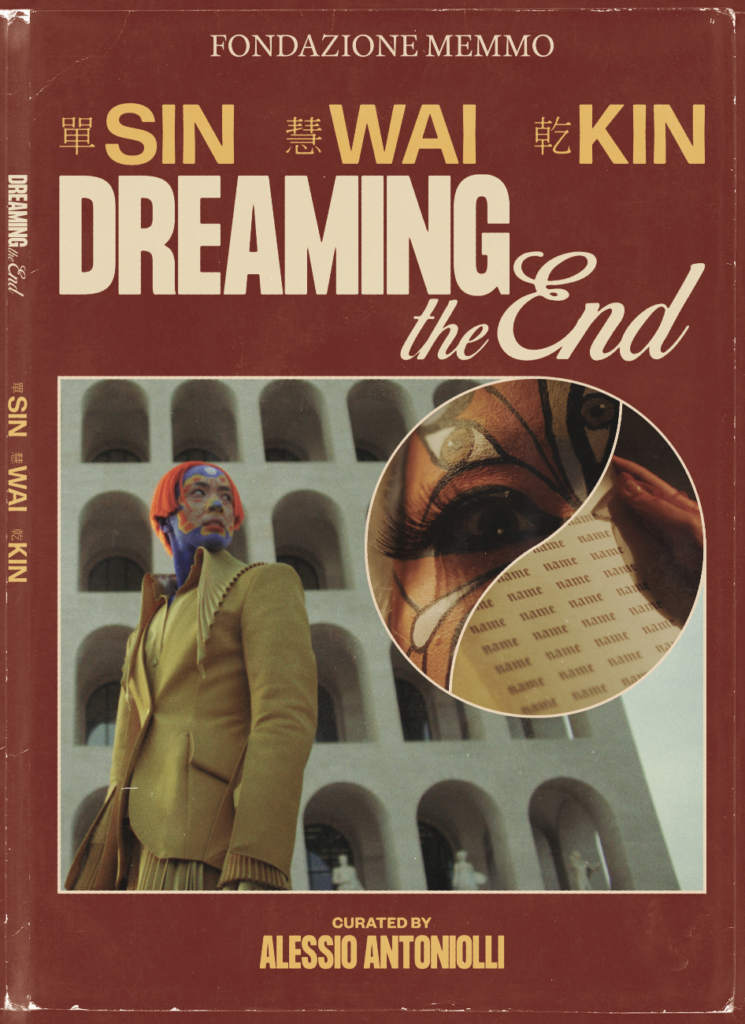

Sin Wai Kin: Dreaming the End

by Theo Gordon

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 19.07.2023

The work of Sin Wai Kin (FKA Victoria Sin; b.1991) employs speculative fiction and modes of drag to (dis)articulate reified categories of identity and their ideological scaffolds across sociocultural infrastructure. Theirs is an art of transfeminist maximalism, using their own body to stage and inhabit different roles across film, digital media and print. Drawing on science fiction and theory, including the work of Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel Delany, Octavia Butler and Donna Harraway, Sin uses fantastical storytelling to counterpoint and unpick the reinscription of normative structures in our world. Their new video work Dreaming the End FIG.1 has a provocative title given its installation in Rome, ‘the eternal city’: a place repeatedly reconstructed and reformed, much like Athens, as one of Western civilisation’s generative foundations, at least since Aeneas supposedly fled the fall of Troy to found the seat of the Roman Empire. Dreaming the End engages precisely with how the repetition of stories and mythology serves to construct the tissue of what we take to be reality, in particular the conception of gender as an intractable, binary system.

Commissioned by Fondazione Memmo and filmed on location in Rome in 2022, Dreaming the End brings Sin’s interests into dialogue with the fabric and history of the city. An imperial, Christian, and later fascist, power, Rome’s cultural prowess has been central to the history of artmaking and the formation of Western art history. It initiated, in Christopher Wood’s words, ‘a cascade of imitable classicisms’ that continue to reverberate through art production and art writing.1 If the queer gaze of Johann Joachim Winckelmann upon Antique sculpture in Rome – to cite one example – inscribed the Classical as an active site of fantasy in the modern discipline of art history, then it is worth noting how that discipline has recently been taken to task for its lack of attention to trans, non-binary and intersex subjectivity and embodiment as lines of political enquiry in the analysis of art and its histories.2 Recently, dedicated issues of Journal of Visual Culture and Texte Zur Kunst, an annotated bibliography in Art Journal and a host of books have underlined that ‘trans’ can no longer remain out of focus in contemporary art and art history, although as Luce deLire notes, ‘it remains to be seen how sustainable these interventions will be’ and whether any material and structural change is to be expected as a result.3

For Sin, ‘storytelling is a human technology of knowledge and truth production’, a practice that positions subjects in ways beyond their immediate control.4 In previous video works, including Today’s Top Stories (2020), The Story Cycle (2022) and The Breaking Story (2022), Sin has explored the authority of the news media and the ways that reality and illusion permeate each other in the realm of storytelling. Thus, Sin’s work engages with postmodern critical practices from the 1980s that attempted to intervene in the political field of televisual representation, updated by the artist to incorporate current incendiary ‘debates’ over trans politics and migration, where phobic reporting has been naturalised in almost every news outlet in the United Kingdom. In Dreaming the End, Sin’s presentation of a speculative trans fantasy in the Roman landscape offers an intervention into the forms of storytelling that buttress art and cultural history, and the inscriptions of identity that emerge from them.

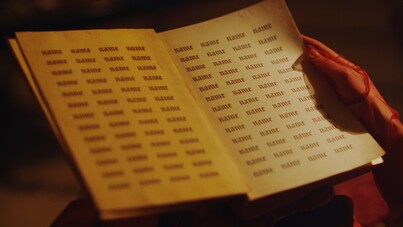

The surreal narrative of Dreaming the End is edited into a loop: there is no beginning or end. A femme named Change, sitting in the opulent interiors of Palazzo Ruspoli, opens an aged, bound book to read the first lines of a story: ‘Once there was a name who lived in name with name’. Change continues to read as the text degenerates into an endless repetition of the word ‘name’ FIG.2. She is subsequently called to a dining room FIG.3, where a masc character FIG.4, the Storyteller, makes conversation only by also repeating the word ‘name’. They each dine on an elaborately sliced apple FIG.5, surrounded by paintings of biblical scenes. Evidently, this is a fallen world, in which patriarchal authority has tipped into comic and painful excess. Eventually Change can take it no longer and challenges the Storyteller to explain whether he is describing reality or telling a story, claiming that ‘every time [he tells] it, it changes a little’. Change leaves the table, striding out of the entrance of Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana – Mussolini’s ‘square colosseum’, an icon of Italian fascist design, which is now home to the headquarters of the designer brand Fendi – before reappearing as a masc character in evening dress, walking through the gardens of the French Academy in Rome at the Villa Medici FIG.6.

Here, Change encounters the Niobids FIG.7, a group of ancient sculptures installed in the villa gardens by Ferdinand de’ Medici in the sixteenth century, later serving as inspiration to Nicolas Poussin, and reinstalled by Balthus when he was director of the French Academy in the 1960s. The Niobids speak to Change in a deliberately ersatz animation, the mouths of the sculptures moving awkwardly to state that ‘when the unreal is taken for the real / then the real becomes unreal’. Change then moves to engage in a dialogue with a sculpture of Janus, the double-headed god of beginnings, endings and transition, about the ways that bodies and stories inform and shape each other. This encounter provokes another moment of metamorphosis: Change spasms and doubles over before standing up as a new femme character FIG.8, wearing an architectural dress inspired by the designs of Cinzia Ruggeri and surrounded by fallen apples. She starts to speak, reflecting on the dialectic between the words she chooses and her own body: ‘I am perceiving myself shaping the words, but I am also perceiving the words shaping me as I speak them’. She begins to walk up the garden stairs, before the film cuts to the Storyteller walking up the steps of the square colosseum. He walks into the sumptuous interiors of the palace, where he reflects on the power of naming: ‘I can’t name the whole out of which things divide, since all names serve to distinguish’. He continues: ‘let me tell you a story’ and Change once again opens the old book.

As this brief summary of Dreaming the End indicates, Sin’s work is elliptical and fantastic, pushing at the plasticity of language and gender that is belied by the disciplinary constraints of patriarchal authority and rigid binaries. Each of Sin’s characters inhabit multiple personae and genders that variously contest and enter into dialogue with the history around them in Rome, particularly the plastic art of sculpture. Sin thus enacts a disidentification in which icons of classicism provoke not conservative replication, but metamorphosis and the possibility of new and different stories. Sin enables a transfeminist politics to emerge; their work is an invitation for the viewer to suspend the reinforced truisms of daily life by entering a speculative realm, before returning to look at life afresh.

The materiality of the installation extends this dynamic by reverberating the formation of identity through multiple forms of print. Sin includes a series of offset lithography film posters, designed to mimic advertisements for Italian post-war neorealist cinema, presented in alternate colourways of yellow, ultramarine and deep crimson. In place of an exhibition catalogue, they present Dreaming the End as a fotoromanzo, a narrative photobook of stills and captions that was a popular cultural form in post-war Italy. A second space houses the four hairpieces FIG.9 worn by Sin in Dreaming the End, which are accompanied by eight face wipes FIG.10 imprinted with the makeup of the different characters, each mounted individually in plexiglass. Using Sin’s face as a matrix, the prints mark an intimate moment of contact, bringing the characters into being through residue.

Sin has reflected that it was through the embodiment and disembodiment of genders in various forms of drag – in particular their erstwhile, now-retired character Victoria Sin, known for a hyper-exaggerated 1950s feminine aesthetic – that they realised they were not a woman.5 Their drag practice opened up a space of trans possibility. Judith Butler’s caution that gender is not a voluntary system – particularly not one of consumption – is rightfully oft-repeated.6 Even so, Sin’s practice does offer the idea that speculative identifications, through dress and drag, can open onto new ways of inhabiting the world. Moreover, the refraction of Sin’s characters in print shows trans embodiment moving across different surfaces, refusing to be confined to one representation or mode of display: appearing between the vibrant colours of video and the makeup wipe.7 Farah Thompson has recently argued that ‘the nurturing of trans art must embrace difference and resist calcification’, and defy the seductions of briefly becoming ‘a lucky pick under neoliberalism’.8 Sin’s focus on crafting speculative narratives aims to unpick those extant in ‘history, religion, science, the news’, and their reinforcement through arts of reproduction, nowhere more powerfully than in the cultural pull of Rome.9 In playful dialogue with the city, Dreaming the End offers multiple images and spaces for different identifications, pointing towards the taking up of new narratives, embodiments and art histories.

.png)