Shoreline Movements

by Matt Turner

Reviews /

Film and moving image

• 26.02.2021

In Hester Blum’s essay ‘Introduction: oceanic studies’, she argues that the sea ‘provides a new epistemology – a new dimension – for thinking about surfaces, depths, and the extra-terrestrial dimensions of planetary resources and relations’.1 Blum contends that ‘in its geophysical, historical, and imaginative properties’, the sea deserves to play a central role within critical conversations surrounding ‘global movements, relations, and histories’. In 2017 the scholar and critic Erika Balsom undertook a residency with the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, as International Film Curator, which resulted in an exhibition, a screening series and the publication An Oceanic Feeling: Cinema and the Sea. Referencing Blum’s essay, Balsom’s project addressed how these conversations can be found within a wide history of cinematic representations of the sea.

Although the chapters in Balsom’s book include productive subdivisions, the ocean is still a vast territory. It is therefore not surprising to see the exploratory parameters noticeably reduced in her latest sea-related project, Shoreline Movements. Curated in collaboration with Grégory Castéra, the film programme was created for the 12th Taipei Biennial in 2020 and was seen remotely by the present author.2 It is made up of eighteen moving image works that explore the point where sea meets land, evading those attempts to survey the entire depths and surfaces of the ocean. With this selective framework, Balsom and Castéra raise an incisive curatorial question concerning collation and presentation: are broad boundaries useful or is it more valuable to look microcosmically at a specific subject? This question is fitting given that the exhibition’s point of focus – the shoreline – is an ‘unusual kind of boundary’: a line that is porous and mobile but still always a point where two things meet.3 The littoral zone of the shoreline is as complex and multifarious as the ocean – a space of contact and conflict, of arrival and departure, of work and trade. It is an environment and ecosystem in its own right; it is also a space in which issues relating to the land, such as migration, climate change and environmental crisis, become more difficult to ignore, manifesting on the shorelines rather than out at sea.

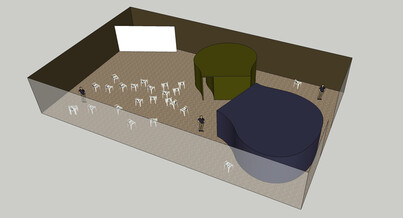

Shoreline Movements is meticulously considered in terms of structuring and selection. The eighteen works are divided into six ‘movements’ of three films, each on view for a period of either two or three weeks. Presented at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum in three separate black box spaces designed by the artist Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, the films within each movement are shown as simultaneous looping installations, intended to ‘come and go like the tides’ FIG.1 FIG.2. The longest movement runs for 166 minutes, and five of the six contain at least one feature-length film. As a curated programme situated in an installation space, the movements themselves exist as something like thresholds: blending the come-and-go rules of engagement in the gallery with the programme format of cinematic presentation.

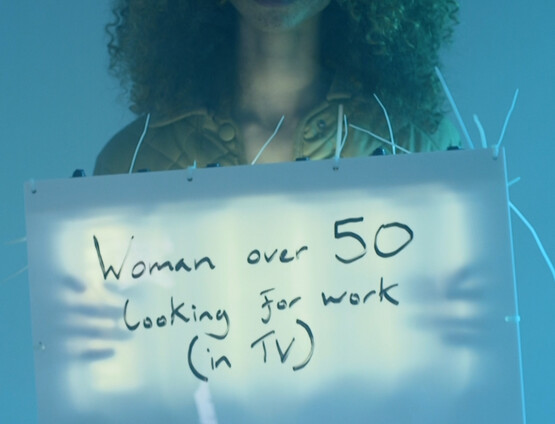

In its entirety, the programme totals nearly fourteen hours. This sustained experience demonstrates how much ground can be covered in a seemingly narrow focal point. The film selection is wide reaching, comprising works made between 1944 and 2020. It is also decidedly international – both in terms of the artists and their chosen subjects – and features various forms of non-fiction filmic practice, from interview-based or observational documentary formats to more essayistic or experimental modes. Whereas some of the works, such as Ben River’s science-fiction inflected Slow Action (2011), look at the shoreline as a fantastical or speculative space, the majority are more grounded, addressing contemporary political realities or traumas of the more distant past. Francisco Rodriguez’s A Moon Made of Iron documents the discovery of three Chinese workers whose bodies were washed up on the Chilean coastline, using disquietingly oblique imagery FIG.3. Looking at legacies of historic exploitation, Patricio Guzmán’s documentary The Pearl Button focuses on victims of the Pinochet regime in Chile, whose bodies were airdropped into the sea FIG.4. Alongside other water-based explorations, Guzmán links these disappearances to another historical act of eradication: how traces of Chile’s indigenous coastal communities have been erased and their stories and traditions are slowly being forgotten.

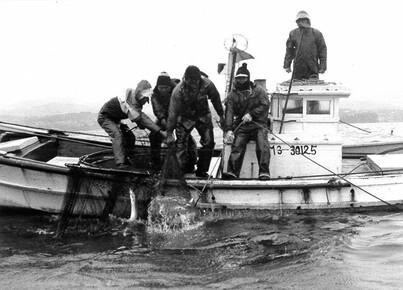

Though many of the works are picturesque depictions of landscape, they are also critical of that which they survey. Noriaki Tsuchimoto’s The Shiranui Sea is the fourth in a series of films the artist made in response to the effects of wastewater leakages from a chemical factory owned by the Chisso Corporation in Minamata, Japan, which caused an outbreak of mercury poisoning. In The Shiranui Sea, Tsuchimoto focuses on the everyday lives of the victims of the incident, recording the stories of those who contend with the ruinous aftermath where they fish and live FIG.5. The film resonates with Hu Tai-Li’s Voices of Orchid Island, which foregrounds the perspective of indigenous communities of an island located forty-four miles off the southeast coast of Taiwan FIG.6. When the island was selected as the site of a nuclear waste storage facility, the islanders resisted. Hu Tai-Li centres their injustice, indirectly revealing how often film-makers speak for the communities they claim to represent, rather than letting their subjects dictate the film’s direction.

Although other films included are more abstract or stylistically experimental, they are equally political in their approach to the shoreline. For instance, Carlos Motta’s discursive landscape study Nefandus explores pre-Hispanic and colonial homoeroticism FIG.7. Using the trajectory of a man travelling in a canoe down the tributaries of Colombia’s Don Diego River, Motta investigates the potential for landscape to hold or reveal embedded histories that have been hidden or are not immediately apparent. Peggy Ahwesh’s The Blackest Sea also uses abstract form to enforce a reconsideration of how the sea and its shores have been represented in the media, reappropriating existing materials to critical ends FIG.8. Repurposing animated footage created by the Taiwanese news network TomoNews, the artist explores how we relate to and consume images of suffering and global strife – especially when such images are defamiliarised through dislocation and distortion. Ahwesh presents a rumination on contemporary crises: migrant boats capsize in the ocean, waste spillages occur off the coastline and dead bodies wash up along the shore FIG.9. Over a period of ten minutes, this film encapsulates many of the subjects that recur throughout the programme, animated through the bodies of disquietingly blank, inexpressive animated avatars.

In her argument for the need to critically contend with the ocean, Blum writes that ‘by shoving off from land- and nation-based perspectives, we might find new critical locations from which to investigate questions of affiliation, citizenship, economic exchange, mobility, rights, and sovereignty’.4 By thinking in littoral terms, Balsom and Castéra chart a new territory entirely, where critical issues relating to the collision of land and sea come into play. Broad, purposefully inclusive curatorial prompts that moving image programmes are often conceived around – ‘landscape’ or ‘labour’, to take two examples – can manifest as staid and imprecise.5 By contrast, this designation of ‘the shoreline’ is novel and impresses through its specificity. As an example of a curatorial proposition that is both usefully limiting and necessarily expansive, it proves a compelling space to explore.