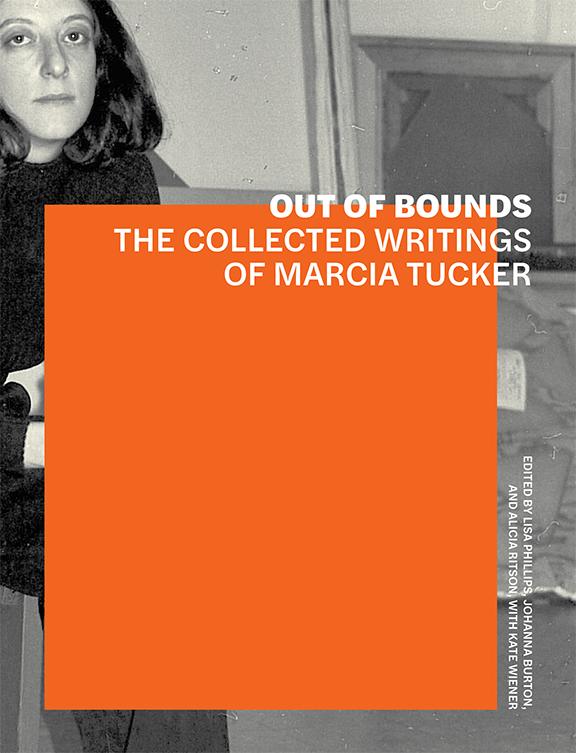

Out of Bounds: The Collected Writings of Marcia Tucker

At the age of thirty-seven the curator Marcia Tucker (1940–2006) took the momentous step of starting her own museum because she wanted ‘to find a place where I could work’ (p.187). The result was the New Museum, New York, which officially opened on 1st January 1977 FIG.1, and the work that followed included a series of such trailblazing exhibitions as ‘Bad’ Painting (1978) FIG.2, Damaged Goods: Desire and the Economy of the Object (1986) FIG.3 and Bad Girls (1994) FIG.4, which made postmodernist art history by helping to frame new notions of artistic value. As well as a gutsy curator and organiser (and stand-up comedian in her spare time), Tucker was a brilliant communicator, witty and inventive, and her lucid explanations of the many developments that took place during her forty-year tenure in the contemporary art world have at last been gathered into a single volume.

‘Visionaries’, the first of three sections in Out of Bounds, is made up of monographic essays on the work Tucker championed, like the ‘pheNAUMANon’ of playful performance corridors that Bruce Nauman built for his solitary, taped performances,1 and Andres Serrano’s dramatic portraits of bodies estranged from both the spaces of ‘high art’ and social norms. Tucker’s career-long commitment to the work of living artists is underscored in the second section, ‘Expanding the Canon’, which rails against art history as a narrative of uninterrupted artistic progress. Her conviction that there can be no single interpretation of a work of art since there is no such thing as a unified audience is stated repeatedly. Time and again the question is asked, ‘By what criteria are we to judge this work?’. Not incidentally, Tucker was fired from her position as curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, for including Richard Tuttle’s 3rd Rope Piece (1974), a short length of cotton clothesline, in a show. Some works, as she said, ‘you just can’t explain in formal terms, and you may just have to fess up and admit that it’s just a piece of rope – thereby putting your life in danger’ (p.244).

One of the book’s main achievements is to establish Tucker’s credentials as an authority on postmodernist art and theory, a designation she would no doubt have baulked at owing to her intense suspicion of so-called expertise: ‘experts are people who are deeply involved in what they already know, and I don’t want to be one of them’ (p.240). She was especially insightful in her assessment of the period’s concerns with issues of representation and its conclusion that there is no such thing as a single reality available for reproduction. Quoting Victor Burgin on the difference between the ‘representation of politics’ and the ‘politics of representation’ – ‘the latter deals with questions of who speaks of and for whom’ (p.121) – Tucker deftly described the debt these debates owed to feminists and their scrutiny of gender at a time when, in the art world at least, the focus shifted from an examination of ‘women artist’s marginalization to the underlying meaning of images themselves’ (p.191).

These ideas are given full range in her catalogue essay ‘Attack of the giant ninja mutant Barbies’ (1994), on the ‘Bad Girls’ of art: women artists such as Carrie Mae Weems and Camille Billops, who used language in their art to ‘curse, rant, and rave’ (p.126) about feminist issues. The essay includes an account of Tucker’s formative membership of that tribe of women who ‘called themselves feminists in the late 1960s and early 1970s – mostly young, white, middle-class, formally educated, and heterosexual’ (p.122), and their commitment to consciousness-raising sessions that helped make issues of inequality personal. The fact that, as Tucker acknowledged, the women tended to speak and listen only to women of the same race and class was without doubt a serious setback for the realisation of the movement’s ambitions, but the conceptual linking of ‘subjectivity, voice, and agency’ (p.126) that these groups achieved, and their subsequent influence on contemporary art discourse, ‘talk about talking’ (p.126), bears repeating.

Nevertheless, concerns about monoglottal feminism are not easily dismissed and in ‘From muse to museum’, a lecture first performed in 1990, Tucker cast her critical eye on those second-wave feminist groups which, with their practical focus on transforming the home and the workplace, ‘were all practice, no theory’. ‘We didn’t’, Tucker confided, ‘ask why the women’s movement was a white, heterosexual, upper-middle-class one, or how issues of race and sexual preference intersected with those of gender’ (p.188).2 As time went on, however, the situation seemed to slip into reverse and the balance between theory and practice tipped in favour of the former so that, according to Tucker, the majority of feminist efforts were now ‘taking place in the arena of criticism and theory’ (p.193) alone.

These histories and debates seem especially relevant at a time when language has never felt more important or dangerous, and are why Tucker’s voice, as someone unafraid to ‘kvetch’ about the state of the (art) world when necessary (and it is always necessary), is worth listening to. Rather than confine herself to the realm of discourse, however vital and far-reaching, Tucker was an enthusiastic advocate of putting theory to work. Today’s recursive arguments about the cultural power and significance of the professional art world are still often made by those content to mull over ‘what belongs where in the lexicon of art forms’ and formulate ‘endless categorical imperatives for different types of work’ (p.156). Against this inherently conservative project stands Tucker’s unshakeable belief in contemporary art’s ability to engage meaningfully with the most pressing social and political issues of the day; a belief matched by her commitment to agitating for real institutional change inside the art world itself.

Tucker’s institutional agenda is given body in ‘Institutional Change’, the book’s third and final section, in which most of the texts are previously unpublished scripts for lectures and ‘fundraising luncheons’. It is here that Tucker’s voice is at its most compelling and distinctive, generous and funny (in contrast to the editors’ rather po-faced descriptions of Tucker’s commitment to ‘engaging diverse publics’ (p.5), a phrase by now heavy with connotations of corporate speak). For although there is plenty of talk ‘about the ideal museum, about a museum of the future – one that is internally structured to eliminate racism, sexism, age discrimination, salary inequities, and unreasonable competition’ (p.177), these words are paired with descriptions of Tucker’s practical attempts to initiate a ‘collaborative, self-critical, and “transparent” organizational model’ that is, of necessity, always in the process of (re)defining itself (some of Tucker’s earliest ambitions for the New Museum included working towards equal pay, rotating jobs, and a transparent budget).3 There’s no expectation that slippery art discourse can do all the work.

In ‘Women in museums’, a lecture given to the American Association of Museums in 1972, Tucker addressed head on the discrimination women were facing in her sector and issued some specific recommendations about what to do about it. ‘Let’s start with hiring practices’ (p.176) was her sage advice and, once again, it is not difficult to make the link between these words, spoken several decades ago, and what’s taking place (or isn’t taking place) inside museums today. Since lockdown began a fissure has emerged, or rather been reinforced, between those on permanent contracts and able to work from home, and workers who service the sector’s buildings and audiences who are much more likely to be precariously employed. The government’s decision to abandon those on Freelance PAYE contracts has been especially devastating for the cultural sector and will surely exacerbate the home counties homogeneity of today’s art world in the long run.4

In ‘The ten most pressing issues in the art world today, and some uncommon solutions’, an unpublished lecture from 1987, Tucker posed the question of ‘What is power in the art world, and who has it?’. Her answer that power is, simply, ‘the status quo’ (p.181), resonates uncomfortably with our current moment when arts institutions behave as if equal representation can be achieved through programming initiatives alone, and rely on unpaid volunteer roles to ‘enrich’ and ‘diversify’ their cultures. As Tucker demanded, ‘Let’s start with hiring practices’ (p.176). Using the right words at the right time matters more than ever. But personal testimony, mea culpa, is not enough. Diverse content is not enough. What we need is arts leaders like Tucker who recognise that the paradigm of equality, ‘can’t just be a matter of programming but has to be somehow inscribed in the heart of an organization’ (p.198). Otherwise the status quo will remain exactly where it is.