Vija Celmins | Gerhard Richter: Double Vision

16.08.2023 • Reviews / Exhibition

While delivering an art history lecture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the protagonist of Teju Cole’s (b.1975) novel Tremor (2023) suddenly breaks off. ‘I am sorry. I’m so sorry’, they say, ‘for about thirty seconds just now I lost vision in one of my eyes’. After a few more moments of apologetic speech, slipping in and out of the academic register, they continue: ‘The vision is coming back and I think it’s best if I press on’.1 Partial sight loss has become somewhat of a motif for Cole, recurring across his novels, photobooks and essays. In 2012 he wrote about his own experience of this phenomenon after he fell asleep while reading Virginia Woolf’s diaries: ‘When I woke up, there was a grey veil right across the visual field of my left eye’.2 As he had been reading of Woolf’s descent into depression, dazzled by the ‘glare of her words’, he wondered, ‘was I like those highly suggestible people who, out of sympathy with something written, drift into an area of darkness?’.3

In the same essay Cole quotes a passage from his novel Open City (2011), in which Julius, a young psychiatrist, ponders the blind spot at the back of the human eye ‘where the million or so ganglia of the optic nerve exit the eye. It is precisely there where too many of the neurons associated with vision are clustered, that the vision goes dead’.4 Julius then proceeds to describe psychiatry as ‘a blind spot so broad that it had taken over most of the eye. What we knew […] was so much less than what remained in darkness’.5 Indeed, the book’s epigraph, ‘Death is a perfection of the eye’, signals from the outset that vision, darkness and ‘darkness visible’, are Cole’s chief modes. Like closing one eye when looking through a camera viewfinder, Cole hopes to find focus in partial sightedness, while acknowledging that much is left out-of-frame. He establishes this theory of ‘faulty’ and yet promising vision in order to scrutinise the systems – or ‘frames’ – by which the West imposes its cultural hegemonies. Cole attempts to shift or distort such frames to bring about a new, more productive, ethical contact between selves and others, histories and presents, presents and futures. These lines of enquiry were integral to Cole’s first photobook, Blind Spot (2017), and are developed further in Pharmakon (2024), in which he continues his investigation into forms of vision, the ethics of framing and the productive tension between text and image.

Unlike Blind Spot, in which each photograph is accompanied by an individual text, Pharmakon intersperses twelve short stories throughout the book. It includes over one hundred images, all of which are devoid of people. The first look up past telegraph poles and the angles of buildings into a clear blue sky FIG.1, and the final photographs are of meditative evening skies – lush, calm, uninterrupted twilights deepening into purple. In between, however, Cole’s viewfinder never rises above the horizon. Most often, the photographs look down at the ground: the base of a classical column, with a takeaway food box jammed in between it and a wall FIG.2; a severed bird wing lying on the pavement FIG.3; corners of seawalls and coastal paths bisecting the view down onto the ocean. In most cases, the photographs display what has become Cole’s signature aesthetic: a soft, milky, pastel palette in a uniform exterior light, and a glancing, over-the-shoulder look at everyday detail. Careful composition is placed in tension with an apparently snapshot mood. The consistent light and absence of geographically defining context put the viewer in any place, and perhaps also any time.

In his debut novel, Every Day is for the Thief (2007) Cole’s narrator watches a carpenter making coffins in Lagos. ‘A tall man in a sky-blue cap rhythmically moves his arms back and forth […] he has one eye closed as he works’.6 Here, half-blindness becomes an image of focus and authenticity, and the ‘sky-blue cap’ one of purity. The narrator contrasts these qualities with the urge to ‘take the little camera out of my pocket and capture the scene. But I am afraid […] that I will bind to film what is intended only for the memory, what is meant only for a sidelong glance followed by forgetting’.7 The photographs in Pharmakon – in their ground-orientated modesty and everywhere-and-nowhere spatial quality – attempt this ‘sidelong glance’ in practice. Cole’s approach recalls Duke Ellington’s advice to television audiences in 1958 when demonstrating his finger snapping technique: ‘one never snaps one’s fingers on the beat, it’s considered aggressive. You don’t push it, you just let it fall’.8 Similarly, Cole allows his view to ‘fall’ onto signifiers of human culture beyond or beside the monumental. To look too directly or too long would be an aggressive, even colonial, act.

The title Pharmakon is a Greek word meaning medicine, poison or scapegoat, and from which the English word ‘pharmacy’ originates. Cole seems, therefore, to capitalise on the idea that art can be seen, by turns, as curative, whether through escapism or social commentary; as ineffectual; or even as a poisonously non-utilitarian indulgence. A number of photographs include abject, toxic-seeming elements, for example a pool of liquid in a battered doorway, with a green leaf dying in its puddle FIG.4. On the following spreads are a series of close-ups of black water pipes, damaged but functional, bearing the remains of flyers – vessels of both information and waste.

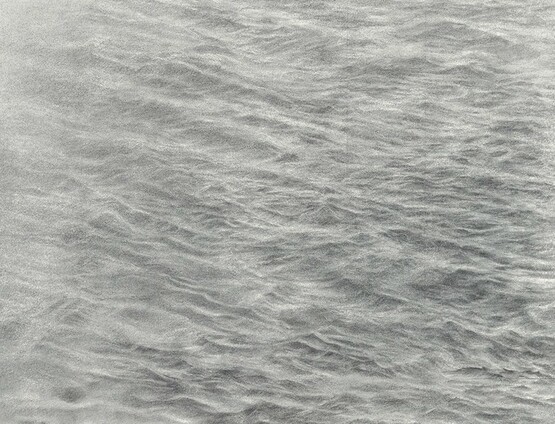

Cole’s title also gestures towards Jacques Derrida’s essay ‘Plato’s pharmacy’ (1968), in which the art of writing or ‘composition’ is described as a pharmakon in all three senses of the word – a means of producing meaning by keeping contradictory meanings in tension with one another. For Derrida, and often for Cole, writing is ‘constituted by differences and by differences from differences, it is by nature absolutely heterogeneous and is constantly composing with the forces that tend to annihilate it’.9 Derrida also wrote that ‘A text is not a text unless it hides from the first corner, from the first glance, the law of its composition and the rules of its game’.10 Cole’s photographs are exactly this: a glance that reveals deeper significance. For example, a block of concrete reaches out of the foreground into a grey-blue sea, flanked by a spit of pebbled land FIG.5. On first impression, the photograph appears decorative and vaguely contemplative, not unlike an ambient album cover or an ambitious holiday snap. Then, one notices the careful way that the concrete bisects the frame – an angular invasion of the ocean’s dappled surface. The natural meeting between shore and sea contrasts with the monolithic, artificial structure. It shows two different relationships with the ocean’s rhythms: snapping on the beat versus swing time.

Although the short texts throughout the book stand apart from the photographs, they nonetheless interact with and inflect them. ‘Now the grass opens its mouths. Now the colours deepen’ reads the end of ‘Portage’, and the palette in the following photographs does indeed deepen.11 The final story, ‘Circle’, presents something of a mission statement: ‘You cannot write about the circle from inside the circle’ it begins, before slightly correcting itself, ‘No, he thinks, that’s not quite right: you could write about the circle from inside the circle. It would have to be possible, and perhaps necessary’. This references Derrida’s idea that literature moves between modes, signalling Cole’s own concern with what is, and is not, included within his frames.

On a 2017 episode of the photography podcast Magic Hour, Cole noted the difference between criticism and art, between ‘what it is to inform someone and what it is to move them’.12 In his photobooks, Cole is certainly trying to move rather than inform, and perhaps this is best achieved in the written elements. It is tempting to describe Pharmakon as lightweight because of its adherence to the strictly ‘artistic’ mode, rather than doing what Cole does best: shifting slyly between the registers of critic and artist. When in Tremor the lecturer’s failing eyesight interrupts his speech, it serves to focus the reader’s attention, calling it back to a thesis that had begun to wander and had become bogged down in academic language. With this renewed concentration, one feels the argument all the more strongly, when faced with the proof that, beyond all reasonable doubt, Western museums should return exhibits stolen during murderous colonial campaigns. Tellingly, this is the most successful point of Tremor itself, stepping over the novel’s fault lines of incompletely fleshed-out characters, mishandled narrative arcs and unbuilt worlds.

Similarly, nothing in Pharmakon displays this level of formal skill and artistry, nor incisive cultural politics. However, Cole’s thesis stands, as does his art, on the argument that one must look through one’s limited lenses – and work within one’s limited frames – to approach some glancing contact with others amid troubled light. As he writes in ‘The Turbine’, the story that falls in the centre of the book, ‘Sometimes when I open my eyes in the dark, I feel that there is something I have forgotten […] Now, possibly, I am coming closer to it’.