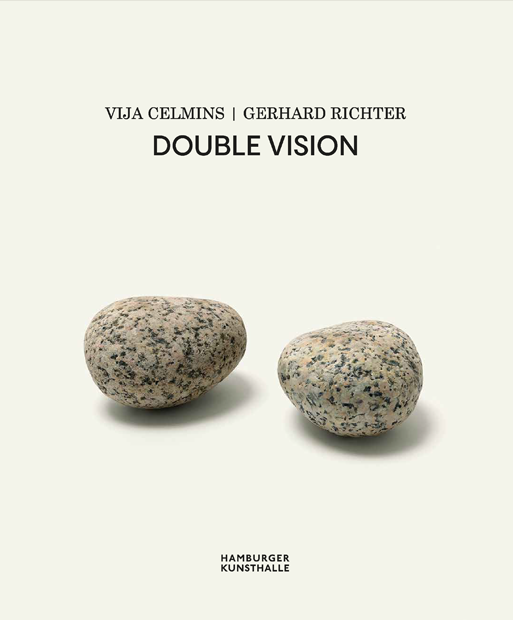

Vija Celmins | Gerhard Richter: Double Vision

by Lisa Stein

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 16.08.2023

The medical term diplopia – derived from the Greek diplous, meaning double, and ops, meaning eye – refers to the experience of perceiving two images of a single object, with one often slightly overlapping or ‘ghosting’ the other. Also known as double vision, the condition can be dizzying, even disorienting, as the brain attempts to merge the two images into one ‘true’ image, facilitating the perception of depth. Moving between works by Vija Celmins (b.1938) and Gerhard Richter (b.1932) is akin to finding oneself suspended between numerous ghost images, none of which is more or less true than the other. The stylistic and thematic overlaps between the sixty largely monochrome paintings, drawings and objects on display at the Hamburger Kunsthalle are remarkable considering that Celmins and Richter worked on separate continents for decades, unaware of each other’s work.1 By foregrounding the genuine affinities between the two artists, the exhibition also reveals subtle differences in the way they explore what constitutes reality and representation, and how the act of seeing can itself be made visible.

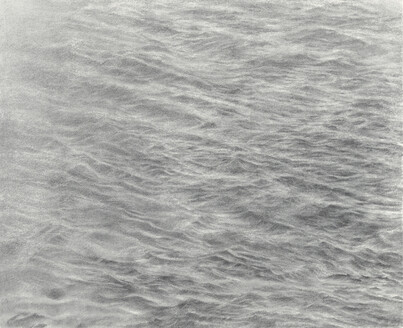

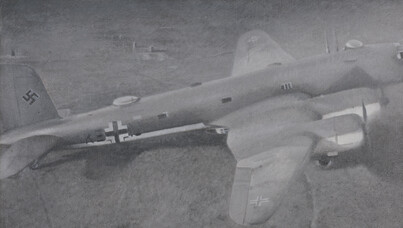

Installed on the second floor of the Kunsthalle’s Gallery of Contemporary Art in eight thematic sections, the exhibition begins with chronologies of each artist’s life and work.2 Born in Riga, Celmins emigrated with her parents and her sister to Germany in 1944, fleeing Russian troops advancing on Latvia, and then to the United States in 1948, ultimately settling in Los Angeles in the early 1960s. Celmins is perhaps best known for her ocean drawings FIG.1, which are based on photographs she took during walks on Venice Pier, not far from her studio. A selection of these meticulous graphite-on-paper works, begun in the late 1960s, as well as a series of six small oil paintings of the subject (1986–87/2012–16) are displayed in section 4, ‘Seascapes’, alongside Richter’s large-scale paintings Seestück (See-See) (Seascape; Sea-Sea) FIG.2 and Seestück (bewölkt) (Seascape; cloudy; 1969). Whereas Celmins’s detailed delineations are seemingly accurate copies of her photographic templates, Richter’s landscape paintings, which are also based on photographs, are often manipulated. For the unsettling black-and-white Seestück (See-See) Richter combined two images of the ocean, one of which he inverted. As the viewer approaches the imposing canvas, what initially appears to be a menacing sky is literally turned on its head. It is in this section, as one’s eyes are lulled by the countless waves rolling through the artist’s seascapes, that one suddenly loses sight of the ocean and becomes aware of perception itself.

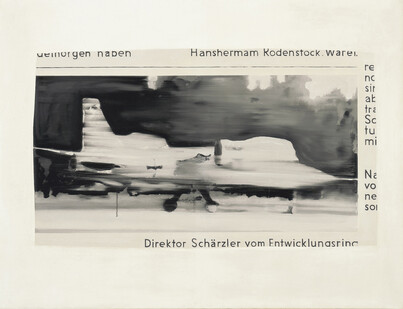

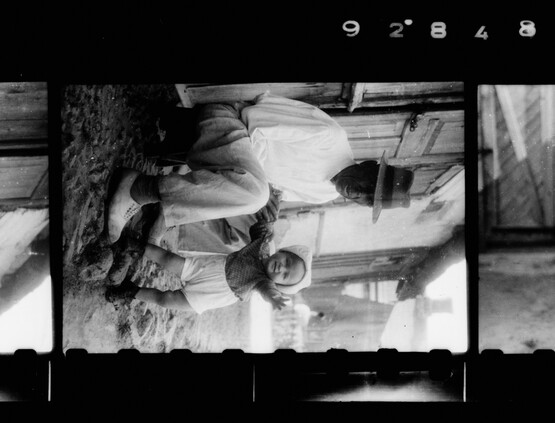

Born in Dresden, Richter escaped East Germany to study art in Düsseldorf in 1961, where he began to use photographs as the basis for his paintings. Like Celmins, Richter was a child of war and the works included in section 2, ‘Disasters’, demonstrate that the artists processed their memories of these traumatic events in almost identical ways. Celmins’s small grisaille oil paintings German Plane FIG.3 and Flying Fortress (1966) are exact copies of found photographs, which the artist collected from flea markets and tore from magazines. Richter’s larger monochrome canvas Schärzler FIG.4 more overtly draws attention to its photographic source material, as he chose to paint part of the newspaper page the image was printed on, including fragments of text. It is worth noting that the year Richter painted Schärzler, Celmins created a similar painting, which unfortunately is not exhibited here: T.V. (1964) depicts a television set, the screen of which shows a burning aeroplane falling from the sky. In their allusion to the image within the image, these works reflect a desire to undercut the illusionism of art, pointing instead to the way we consume images.

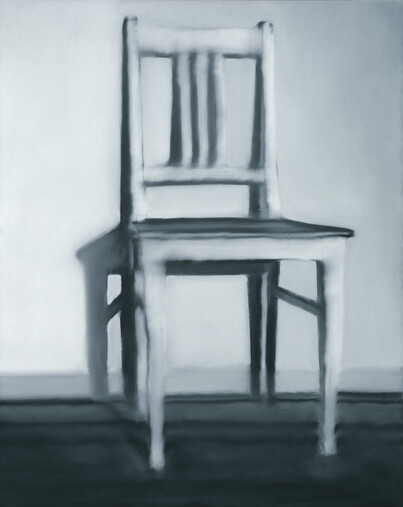

Shortly before Celmins began using photography as an ‘intermediary’, a ‘fundamental means of physically distancing herself from her subject matter’ (p.136), she created decidedly flat still-life paintings of objects in her studio, which were motivated by an impulse to unlearn what she had been taught at art school.3 Inspired by Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964), Celmins created such works as Hot Plate FIG.5 and Lamp #1 (1964) using a painting technique that ‘did not call attention to its own effects’.4 These early works are grouped together with Richter’s monochrome still lifes of kitchen chairs FIG.6 and a curtain in the exhibition’s first section, ‘Everyday Objects’. Just as Celmins’s early paintings signal a burgeoning preoccupation with the physical presence of a work of art, Richter’s use of blurring in his still lifes – he often smeared newspaper photographs with a chemical solution before he painted them – undermines ‘the initial understanding that the paintings are direct portrayals of reality’ (p.71). Contained in a makeshift aged-pine frame, the artist’s small trompe-l’œil painting Vorhang (Curtain; 1965) – a pictorial device with a long history in painting used to heighten the illusion of three-dimensional space – is noteworthy in this regard. The perfectly executed folds of monochrome fabric, which make up about ninety per cent of the canvas, draw the viewer into the painting, only to reveal the crudely finished floor beneath the drapery.

The visual deceptions continue in section 7, ‘Back to the Tools’. Four more small trompe-l’œil paintings by Richter, each resembling a sheet of paper curling upwards as though it were being removed from a notepad FIG.7, are displayed next to Celmins’s Blackboard Tableau #14 (2011–15), a writing tablet in a wooden frame alongside a faithful copy, cast in resin, onto which the artist has laboriously transferred every scratch and trace of chalk. Although Richter’s paintings and Celmins’s sculptures appear to have the same objective, the differences between the two artists become most apparent in this section of the exhibition. Whereas Richter’s works are often firmly rooted in, and arguably limited by, the pictorial genres they reference, Celmins’s sculptures – such as the ‘constellation’ of stones that she collected in the desert with their cast bronze painted doubles, To Fix the Image in Memory (1977–82) or her oversized pink eraser FIG.8 – are as much about the act of remembering and making as they are about close looking. It was in the context of her ocean drawings that Celmins used the term ‘redescribing’ for the first time, perhaps anticipating the experience of the viewer, who, moving around her stone sculptures and closing in on her elaborate drawings would, by tracing the artist’s numerous marks, partake in a redescribing of the surface.5

Perhaps the most striking overlap among the many examples in this well-executed exhibition are two sculptures resembling rolling ball puzzles. Such dexterity games became popular in the late nineteenth century and often contained images of popular figures or historic events, including wartime scenes. The circular plane of Celmins’s WWII Puzzle Toy (1965), which is encased in a clear plastic dome, depicts a crashing, burning warplane, a jarring combination that speaks to her experience of war as a child. Although the black-and-white photograph of a gloomy staircase in the background of Richter’s rectangular Kugelobjekt I (Spheric Object I; 1970) is less controversial, the lack of holes into which the metal balls can roll conveys an equally bleak idea about childhood and the ultimate futility of playing. Displayed in close proximity, where ‘Everyday Objects’ leads into ‘Disasters’, these works stand out in the artist’s respective bodies of work, further amplifying the affinity between the two.

The past five to ten years has seen an increase in exhibitions that pair artists, with some combinations more coherent than others. Brigitte Kölle, the Kunsthalle’s Head of the Collection of Contemporary Art, deserves praise for bringing together Celmins, who in Germany is still little known, and Richter, whose established œuvre can be assessed in a new light, and presenting them as ‘equals’ (p.24) – although, notably, given Richter’s notoriety, Celmins was initially sceptical about her involvement in the exhibition. Both artists, each in their own way, exploit the permeable boundary between the natural and cultural components of vision, creating work that requires slow looking. As a result of the proliferation of images being shared on a daily basis and the limited time we have to process them, this way of looking is gradually being unlearned. Our increasingly superficial engagement with images only benefits those who share misleading, manipulated or false information online. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, dramatic images and videos, many of which were taken at a different time and place or had been digitally altered, were shared widely on social media. A number of ‘photographs’ generated with AI have recently been circulated in the belief that they were real, with one such image even winning a prestigious photography award.6 By making us question if we can trust our own vision, Celmins’s and Richter’s works remind us to be vigilant when looking at the innumerable images that shape our world today.

Exhibition details

Footnotes

- Confirmed by the exhibition curator, Brigitte Kölle, in email correspondence with the present author, 9th August 2023. footnote 1

- These are also reproduced in the bilingual (German and English) catalogue. footnote 2

- Catalogue: Vija Celmins | Gerhard Richter: Double Vision. Edited by Brigitte Kölle. 256 pp. incl. numerous col. + b. & w. ills. (Verlag Walther König, Cologne, 2023), £34. ISBN 978–3–7533–0403–8. footnote 3

- R. Ferguson: ‘The image found me: Vija Celmins in Los Angeles’, in G. Garrels, ed.: exh. cat. Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory, San Francisco (Museum of Modern Art), Toronto (Art Gallery of Ontario) and New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2018–20, pp.56–63, at p.60. footnote 4

- ‘One decision was that I was going to go back to a more abstract kind of work […] that kind of double reality, where there’s an image, but the image is here in another form, and […] when you look at the work, you have that double thing you should have all the time, when you’re looking at the making […] a kind of redescribing of the surface, and the image is interwoven with that surface’. Vija Celmins, quoted in G. Garrels: ‘Vija Celmins: to fix the image in memory’, in idem, op. cit. (note 3), pp.12–23, at p.13. footnote 5

- Boris Eldagsen’s The Electrician (2022) won the Creative category of the 2023 Sony World Photography Award. He later refused the award on the basis that his entry had been generated with AI. See J. Grierson: ‘Photographer admits prize-winning image was AI generated’, The Guardian (17th April 2023), available at www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/apr/17/photographer-admits-prize-winning-image-was-ai-generated, accessed 14th August 2023. footnote 6