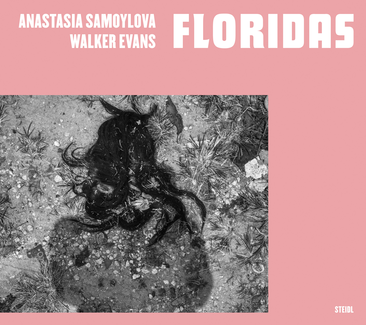

Floridas by Anastasia Samoylova (b.1984) is clothbound in Pepto-Bismol pink, a shade that conjures up visions of the peninsula’s architecture and self-perpetuating mythology.1 Whereas Samoylova’s previous project FloodZone (2019) – compiled in the wake of Hurricanes Irma and Maria – was preoccupied with impending environmental collapse, Floridas fragments this focus into a multiplicity of impressions of the state, fully inhabiting its contradictions. After moving to Miami six years ago, the Russian-born artist immersed herself in the oddities of her new home, embarking upon intensive road trips to understand something of Florida’s collective psyche. Soon after, she encountered lesser-known photographs of the state by Walker Evans (1903–75) taken between the 1940s and 1970s.2 The affinity between these series was translated into a book, with Evans’s views of Florida printed alongside her own. Five of Evans’s faux-naive paintings, made between the 1950s and 1960s, of palm trees and ramshackle buildings are also interspersed here, rendered in neutral tones with the odd shot of colour.

Known for its popularity with tourists and retirees, its rapacious real-estate development and the glamour of cosmopolitan Miami, Florida is also acutely polarised and widely regarded as America’s dysfunctional punchline. Long riven by inequalities emblematic of the nation at large, Florida has grown practised in masking its crumbling social and physical infrastructure with a cheerful gloss of paint and a pageant smile to the outside world, which succeeds to some extent in making believers of its own residents.3 Part of this self-delusion manifests as paralysis in the face of rising sea levels and the hurricanes that plague its coastal communities: the only forward motion appears to be the perpetual expansion of property along the lucrative shoreline, even as the waters encroach.

Samoylova largely avoids making explicit statements in her work, instead allowing her subjects to readily convey the slow horror of denial in the face of collapse. This is observed in the frequent collision between vitality and decay in her photographs: russet oxidation and veridian mould bloom across saturated stucco walls and ship hulls. The threat of death, man-made or otherwise, is close at hand in Gun Shop, Port Orange (2019), which depicts a shop painted an immaculate, Floridian mint-green and adorned with silhouettes of rifles; or the alligator in an empty, candy-coloured pool in Gatorama FIG.1, which is paired with a painting by Evans in similar hues FIG.2. A formally accomplished street scene, Residential Neighborhood with a Chemical Plant, Panama City (2021), trades in the inherently disturbing imagery of domesticity in close proximity to toxic industry.

Samoylova gained early recognition for her Landscape Sublime series (2013): faceted sculptures composed of collaged stock images of landscapes, which she subsequently photographed. In Floridas she presents the refracted typologies of a state, and one with a similarly lurid, brash aesthetic. Whereas Evans engaged with a rueful wink and at a remove – as David Campany notes in the book’s accompanying essay, ‘when Evans addresses the picturesque it is by quite literally photographing a rack of postcards’ (p.170) – Samoylova often appropriates precisely this glossy, commercial aesthetic. The book opens with a commissioned short story by Lauren Groff, which sets the scene of materialist promise before the scales fall away to reveal the cruelty beneath the surface illusion. Groff’s story is titled after Samoylova’s Venus Mirror, Miami FIG.3: a photograph of a mannequin’s torso caught in the vibrant reflection of a shop window, alongside ubiquitous Floridian palm trees. Campany suggests that there is truth to be found in this depiction of surface, that these photographs only appear to be a faithful replication of the image that Florida broadcasts to the world: ‘To accept the look of the place, while knowing that its obviousness is the way to deeper understanding’ (p.178). That, in essence, these images turn Florida’s kaleidoscopic mirror – an aqueous reflection or the gleam of a car’s bonnet – back on itself.

There is, however, a far shrewder form of exposure in Samoylova’s playful, absurdist photographs. For example, her experiments with photographic trompe l’œil, in which she abstracts commercial hoardings and billboards at close range and places them in strange juxtaposition to their urban landscape; or, in the book’s cover image, showing her shadow superimposed on a discarded wig (2017), which functions as both artistic assertion and humble vanitas; or even an uncanny photographic ‘collage’ of a silhouetted pillar, shown alongside the statue of a lion, which, flattened in the harsh sunlight against a typically pink Sarasota wall, appears to have been artificially inserted.

A background in architectural photography ties Samoylova and Evans together – specifically, their mutual understanding of how the architectural landscape can be read as culture, and how its reception is mediated by the camera. As Campany writes, ‘Like Samoylova, [Evans] was fascinated with the camera’s way of describing built form, turning what is photographed into a strong if not always obvious sign of itself. Photographs can permit architecture to be read as an oblique portrait of a society’ (p.175). From the Neo-classical pillars of suburban houses to a gargantuan statue in Pegasus and Dragon, Hallandale (2020) – a monumental, kitsch mascot for a horse-racing track – Graeco-Roman imagery proliferates throughout. Samoylova draws parallels between Miami and Venice. With both cities slowly being subsumed by the sea, and through the Italianate architectural elements and brightly coloured façades popular across Florida, she is left with the impression that ‘the cities are being patched up as they’re falling apart’.4

One of the unexpected pleasures of the book, in which all captions are relegated to the back, is that the photographer’s hand is not always apparent in these images. Many of Samoylova’s black-and-white photographs inhabit the same Floridian Gothic as Evans’s, replete with antebellum architecture and trailing Spanish moss. Most surprising is a colour image of a grounded boat FIG.4, taken by Evans in the 1960s; its dramatic chiaroscuro and careful composition lends it a sombre elegance at odds with many of the other photographs in the book. Evans had arranged for rolls of unused colour photographs to be given to the Rybovich family, owners of the pictured boat works, for safekeeping, prompting Samoylova to revisit Evans’s tribute to the family business in 2021 FIG.5.

Samoylova’s Floridian landscapes are largely unpopulated. She is wary of documenting immediate catastrophe and resists a photojournalistic impulse. And yet, it would be disingenuous to omit the undeniable: a simple black-and-white photograph shows a man wading through water, captioned Resident of Miami during Flooding (2020). It is rarer still to see a photograph in the series taken at quick shutter speed, such as Marjory Stoneman Douglas House, Miami (2020), which is pictured across a verdant lawn with drops from a sprinkler frozen in the sunlit foreground; Douglas, who died in 1998, was a conservationist renowned for her efforts to preserve the Everglades.

If it was ever her intention to distil or fix some idea of Florida in her mind, one imagines that Samoylova quickly came to the realisation that the best she could hope for was to observe the many shifting facets of the mirage. Florida may be a bellwether or microcosm of the state of the nation but, historically and geographically, it is unique. Its idiosyncrasies and disparities register starkly for the artist, and it is her stance as a relative outsider, perhaps, that enables her to dig at a slightly deeper truth. She absorbs the lessons of Evans’s unconventional documentary style, keeping a sense of perspective while surrendering to Florida’s ultimate unknowability. She conveys the fabric of the peninsula as a tangle of incongruities, a decaying façade about to collapse in on itself, foundations corroded by the waters’ incursion.

Footnotes

- David Campany delves into associations with the colour in his accompanying essay to Floridas: ‘When pink occurs organically (skies, flowers, exotic birds) it is a sign of vitality. By contrast, the man-made pinks of buildings, décor, and commodities revel in artifice. They are sugary, often camp, and in danger of trying too hard. Pink can feel depthless, as thin as an image, which goes some way to explaining why it is so photogenic’, p.174. footnote 1

- Evans first photographed Florida for Karl Bickel’s book The Mangrove Coast: The Story of the West Coast of Florida (1941). The resulting free-standing sequence of images echoes his renowned work from earlier in the same year, Let us now Praise Famous Men (with a text by James Agee), in which Evans’s photographs only obliquely illustrate the text, characteristic of his unconventional approach. footnote 2

- As noted by Campany, Miami’s famed, pastel-hued Art Deco buildings were once the uniform white of the modernist International Style, only to be brightly painted later in the twentieth century to counter the image of the city as a cocaine-fuelled gangster’s paradise, p.174. footnote 3

- Anastasia Samoylova, quoted from J. Goldman Kay: ‘Florida Gothic’, The Bitter Southerner (9th August 2022), available at bittersoutherner.com/feature/2022/florida-gothic, accessed 5th June 2023. Campany also explores the American perception of Neo-classical architecture as being synonymous with ‘institutional credibility’ (witnessed in the nation’s civic buildings and grand Palladian homes, particularly famous in the plantations of the South), later coming to be ‘identified as much with formulaic McMansions and shopping malls, which Samoylova inherits as a Florida norm’, p.175. footnote 4