A portrait is always a portrait of power. Where this power lies, however, is a vexed and complicated issue. In her book Ethical Portraits Hatty Nestor explores the contested space – both material and representational – of the portrait when it collides with the brutal realities of the carceral system. Images of the human face are integral to contemporary legal structures: ‘wanted’ photographs and composite sketches are disseminated to capture suspects, mugshots are taken of those who have been arrested, courtroom sketches are made of defendants and, if convicted, these individuals are subject to a regime of highly invasive visibility, despite being removed from visibility in wider society. Nestor’s book examines how power dictates the circulation, and obfuscation, of the faces of those who have come into contact with the American legal system and find themselves enmeshed in the structures the carceral state produces.

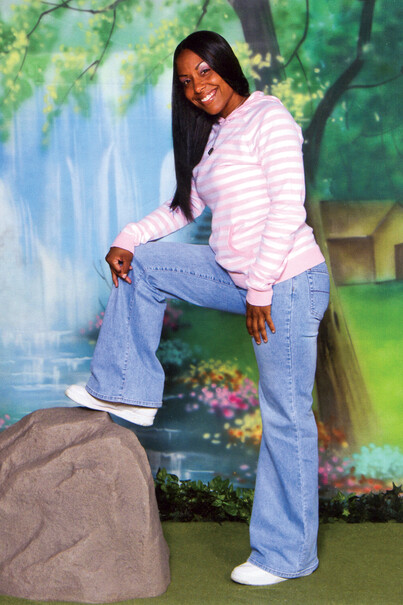

Although Nestor’s book raises a number of troubling questions for readers, it is perhaps most driven by one that she poses in her introduction: ‘who has a right to representation on their own terms, and for whom is this right obscured or denied?’ (pp.14–15). Rather than offering a direct answer to this question, Ethical Portraits recounts the stories behind such denials and obnubilations. The book is divided into seven chapters and includes discussions with the courtroom sketch artist Priscilla Coleman, the activist-artists Andrew Tider and Jeff Greenspan in relation to their project that compares ‘portraits of those held accountable for their crimes with those who aren’t’ (p.50), the artist Alyse Emdur, who has photographed inmates in prison visiting rooms as they pose beside uncanny landscapes FIG.1, and two artists, Alicia Neal and Heather Dewey-Hagborg, who have each produced portraits of the American political dissident and educator Chelsea Manning. The chapter on Dewey-Hagborg is distinct from the the essayistic chapters that precede it in that it follows a question and answer format. Using the work of these artists as a starting point, Nestor explores themes of accountability, agency and power asymmetries in regimes of visual production.

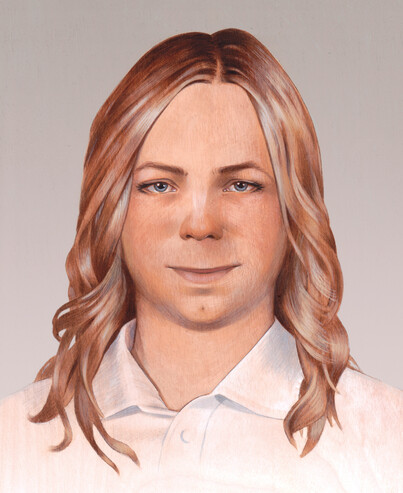

In 2014 Neal was commissioned by the advocacy group The Chelsea Manning Support Network to paint a portrait of Manning for circulation in the media FIG.2. Prior to this, Manning was generally represented by images that consciously misgendered her or were not intended for public circulation. In creating the portrait, Neal’s focus was to give ‘[Manning] the dignity of at least being seen as who she wants to be’ (p.25). As Nestor elaborates, ‘Neal’s portrait is a reminder that Manning’s identity has nothing to do with her imprisonment. It reminds us that we are not solely defined by the institutions and environments we are subjected to and conditioned by’ (p.28). In meeting and discussing the work with Neal, Hestor formulates her most explicit definition of what constitutes an ethical portrait: ‘a depiction of someone which holds political weight, is integral and empathetic, which challenges marginalisation through a visual image’ (p.24). Although readers may have their own addenda to such a definition, it provides a framework for Nestor’s selection and analysis of portraits in this volume.

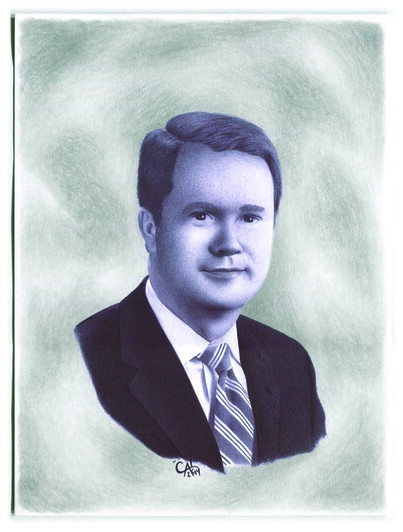

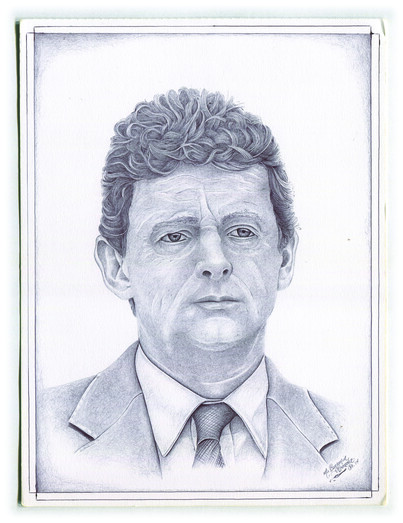

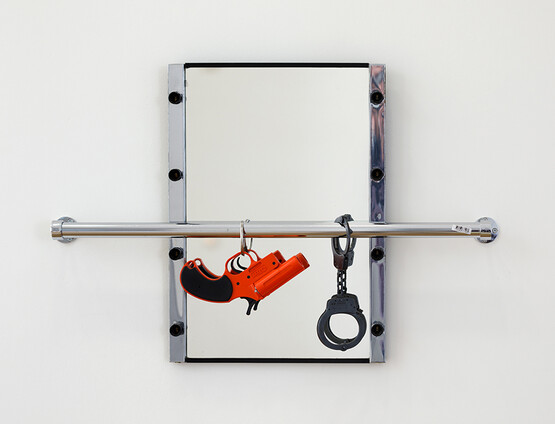

Much more complex is Tider's and Greenspan’s Captured Project, which the artists describe as ‘people in prison drawing people who should be’ (p.50). They work with inmates in prison art programmes, providing them with portraits of CEOs implicated in grand labour and environmental abuses that, despite their extremity and scale, remain largely legal. The resulting works, which represent some of the most intriguing included in Nestor’s book, are portraits of portraits. The malefactors depicted include C. Douglas McMillon of Walmart, who Charles Lytle depicts with a kind of vacant bonhomie FIG.3, and BP’s hapless Tony Hayward, infamous as the CEO who oversaw the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Benjamin Gonzalez Sr depicts Hayward with an eerie gorgon-like stare FIG.4. The artists convey some of the studied blandness of corporate portraiture, but also the personal vacancy that unifies these images – a reflection of business personas they inhabit, which, in turn, eventually come to inhabit them. Nestor acknowledges that Tider and Greenspan’s project is not without controversy, noting that the artist inmates are ‘only rendered visible through portraits of those who are free’ (p.58). She considers the work a starting point rather than a successful advancement of ethical portraiture. Although inmates are returned a modicum of agency, and the injustices of the ‘justice’ system are inscribed in the works, Nestor remains ‘unsure’ of how much the project ‘recounts the lived position of the artists involved’ (p.60).

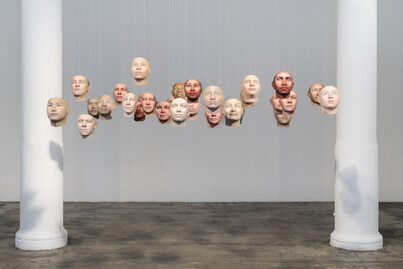

The visual works included in Ethical Portraits span considerable formal and conceptual territory. In addition to the images from The Captured Project, there is a black-and-white reproduction of Neal’s Manning portrait, as well as a number of Coleman’s courtroom sketches. Coleman’s works are intriguingly lurid, not least an image from 2013 featuring the late singer Amy Winehouse in court ‘extending her leg and hitching up her dress, in order to demonstrate to the court her slight frame as evidence of her innocence’ (p.33) FIG.5. However, innocence is not the first word that comes to mind when looking at Coleman’s rendering of the event. The images from Emdur’s Prison Landscapes series FIG.6 are eerie and strangely melancholic, heightening the contrast between the grim institutionalism of prison spaces and the jaunty, almost kitsch backdrops in their visiting rooms. Dewey-Hagborg’s Probably Chelsea FIG.7, thirty 3D printed renderings of Manning’s face created using DNA analysis, also makes for uneasy viewing. Displayed hanging from individual wires, these disembodied ‘possible portraits’ of a prisoner jailed for alleged crimes against the state evoke the dark history of institutionalised beheading.

Traditionally, aesthetic theory has been concerned with formal matters, and the discipline of ethics has often undervalued lived experience in relation to abstract principles. As such, Nestor’s book is a provocative, interdisciplinary intervention. However, considering it addresses such urgent matters, the publication is shockingly compact, at just over ninety pages long. For many readers, particularly those from an arts background, who are approaching the subject of the prison-industrial complex for the first time, this may work in their favour. Nestor certainly does not claim it to be an encyclopaedic treatment of the topic and, of course, there is no book long enough to chronicle the cumulative horrors of incarceration in a country where crime and punishment are fodder for media spectacle – as evidenced, for example, by the ride-along exploitation reality show Cops, which boasted as many seasons as The Simpsons before its cancellation after the murder of George Floyd. However, although Nestor’s svelte chapters are informative, the book ends rather abruptly. Instead of a summative concluding chapter, Nestor’s interview with Dewey-Hagborg gives way to notes and acknowledgements. Ethical Portraits opens the door to some of the most profound structural and aesthetic questions of the moment; one hopes if Nestor returns to the subject she will be given a chance to open that door even wider.