In 1929 André Breton (1896–1966) wrote that ‘the simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd’.1 Around ninety years later the presidential candidate Donald Trump said something oddly similar: ‘I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot someone and I wouldn’t lose any voters’.2 It is, then, not completely absurd to note the surreal – if not Surrealist – impulses of recent right-wing international politics and the dismantling of reality that accompanies the careful administration of such adjectives as ‘post-truth’. Although the idea of Trump as an avid proponent of Breton’s manifesto may be a stretch too far, the tactics – however distorted – of Surrealism and its various conceptual descendants have found a strange power in the acquisition and maintenance of political capital. A second example can be found in Vladimir Putin’s former right-hand man, Vladislav Yuryevich Surkov, who once told the Atlantic that his ‘portfolio at the Kremlin and in government has included ideology, media, political parties, religion, modernization, innovation, foreign relations, and [...] modern art’.3

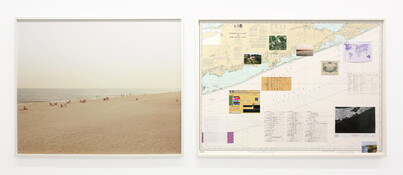

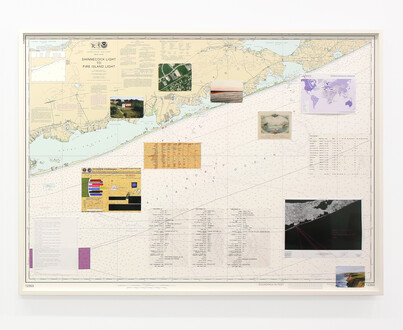

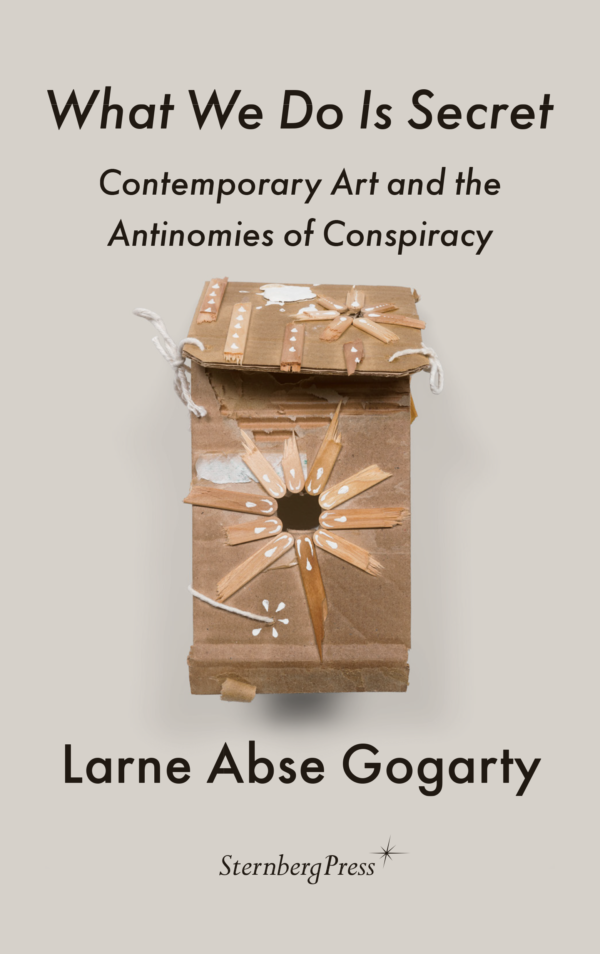

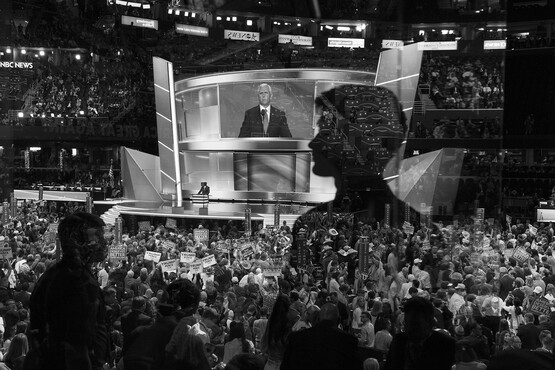

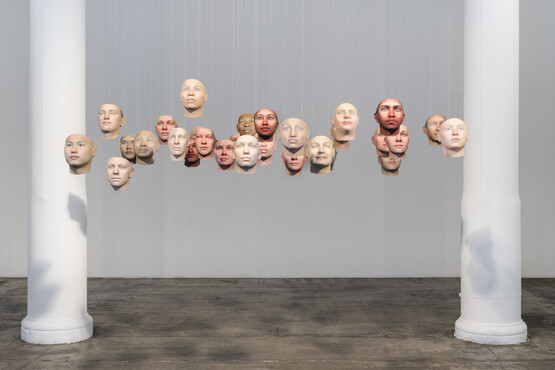

For a long time the worlds of art and populist politics have been complexly imbricated. Such an entanglement, and its possible unthreading, is the focus of Larne Abse Gogarty’s What We Do Is Secret: Contemporary Art and the Antinomies of Conspiracy, a new volume in Sternberg Press’s On the Antipolitical series. The aim of the book is ‘to consider the question of conspiratorial logic in relation to artistic practice’ (p.31).4 Conspiracy is crucial to the strategies of the alt-right and, Gogarty suggests, to the aesthetic practices of certain contemporary artists. She cites a wide range of cultural figures, movements, works of art and miscellanea. She considers the photographs of NSA undersea fibre-optic cables by Trevor Paglen (b.1974) FIG.1 FIG.2, which attempt ‘to make visible the activities of shadowy state agencies including the US National Security Agency and the Central Intelligence Agency’ (p.81) by overlaying the various strata of information that reveal infrastructures used to connect – or surveil – us. Other referenced artists include Sondra Perry (b. 1986) FIG.3, Cady Noland (b.1956) FIG.4 and Babak Radboy (b.1983) and Roe Ethridge (b.1969) FIG.5. Elsewhere, there are sharp-eyed critical responses to the play of text and graphic in memes – another possible Surrealist influence – as well as discussions of Karl Marx and the anonymous imageboard website 4Chan.

In terms of critical influence, Fredric Jameson is the most persistent spectre here: his development of ‘Postmodernism’, as well as his more particular concept of ‘cognitive mapping’, recur as necessary touchstones and are, for the most part, built on persuasively through the various aesthetics of contemporary artistic practice.5 In addition to the conceptual, Abse Gogarty’s style and syntax can also betray a distracting Jamesonian density: pith is not a priority. The reader is, for large portions of prose, adrift in a sea of ‘isms’. The structure of the book reveals much in this regard. It is split into four chapters, which bear such titles as ‘History against Origins: On the Politics of Post-internet Aesthetics’ and ‘Inert Universalism and the Info-optimism of Legibly Political Art’, and sub-sections including ‘Flat-unmediated-aspirational-nihilism’ (p.48).

The latter is the author’s terminology for aesthetic practice that dangerously attempts ‘a totalizing and blended sense of the world’ (pp.48–49), one that finds its distilled expression in the work of Timur Si-Qin (b.1984). She references in particular his installation A Reflected Landscape (2016), in which a flat-screen monitor is situated in a landscape made of plaster, sand and artificial and living plants, strewn with graffiti and rubbish, including empty Coke bottles. The work is branded by the artist’s ‘NEW PEACE’ logo, which he has stamped across various aspects of his work since 2016. The danger, in Abse Gogarty’s view, is that this merely reflects the landscape of a politics that has also dispensed with proper meaning in public discourse and debate, and is otherwise powered not by people but by corporate demagogues. In Si-Qin’s semi-fake mini-world, just as in our current polity, one thing continually defines, and undefines, another: semantics are trashed and juxtaposition becomes incidental in a brand of slick, frictionless surface. Its wry meaninglessness becomes its only point; its conceptual depth is a trompe l’œil.

Abse Gogarty deftly notes how this sense of the world has wormed its way into post-internet political culture: in the shrugging deference to ‘irony’ that structures the rhetorical content of such forums as 4Chan. But there is an attendant stylistic concern: is Abse Gogarty’s complex language justified by the intricacies of the post-internet problem, or does it simply perform the same kind of conspiratorial obfuscation that it attempts to explore? Take this sentence, for example:

This is not, incidentally, the end of post-internet aesthetics that leaned heavily on the ontological turn and accelerationism as its guiding philosophy, and it has the possibility of coherence with the alt-right in the same way that accelerationism has right and left strains, as well as how aspects of new materialism, and the ontological turn, often share a post-human vitalism and de-historicizing impulse with transhumanism and neo-reactionary thought (p.49).

Here, ‘isms’ threaten to become convenient bywords for what are complex and often self-contradictory movements involving a great many minds. Postmodernism contains multitudes and it is easy to allow the word itself to numb any kind of nuanced, tentative or otherwise doubtful response to the things that happen under its long shadow. Moreover, are hyper-hyphenations such as ‘flat-unmediated-aspirational nihilism’ helpful, or are they another kind of flattening and ill-defined surface – another Reflected Landscape?

Abse Gogarty offers two possible answers to this dilemma. The first is a lurking sensation that these verbal rabbit holes are intentional, that they constitute a kind of performatively paranoid reading. This is not, on this reviewer’s part, too conspiratorial: she quotes Danny Hayward’s desire to write ‘in the spirit of the work itself’ (p.33) and goes on to say that she seeks ‘out ways of writing alongside the artworks and ideas under discussion here through assuming a proximity with their operation’ (p.34). It is a risky move – one that relies on a generous reader. The second possible answer is simpler but more convincing: that Abse Gogarty’s passionate interest in the work is readily felt. This is most evident in her moving invocation of the late poet Sean Bonney; her detailed discussions of what she calls ‘legibly political art’ (p.76) and the sublime-as-information-overload; her more personally inflected coda; and her treatment of Noland’s chain-link fences.

Abse Gogarty sets out to move beyond readings of Noland’s work as ‘a generalized statement about the extremes of US celebrity and commodity culture [...] and towards addressing her work in relation to longer histories of property, knowledge, violence, and conspiracy’ (p.101). For example, she writes about 12’ 6” Chainlink Fence (1992) in reference to the growing prison industrial complex in the United States. In this system, individuals become capital and Abse Gogarty demonstrates clearly the ways in which this horror is expressed in Noland’s chain-link installations, which evoke both the primacy of private property and a deep-seated fear of others. Moreover, given the partially transparent nature of fences, author and artist remind us that the inner workings of these systems are not that difficult to see and that the conspiratorial and the evident are sometimes – perplexingly – one and the same.

Indeed, people like Trump and Surkov wear their heartlessness on their sleeve. Their conspiracy is conducted out in the open: nothing matters, and that fact can be weaponised. Abse Gogarty provides a detailed map of such tactics and the violence they can do. By extension, she demonstrates how contemporary art can become either dangerously bound up with the depthless sheen of populism – as in the work of Si-Qin – or, conversely, uncover the painful consequences of Western liberalism through a recycling of the materials that symbolise its callousness, as in the work of Noland. What We Do Is Secret makes clear there is much to be done if works of art are to truly resist the allure of political systems in which truth has become unfashionable. However, Abse Gogarty has made a valuable contribution and – despite an onslaught of ‘isms’ – this is a meaningful book in a world in which meaninglessness is often the smoking gun.

Footnotes

- A. Breton: ‘Second Manifesto of Surrealism’ [1930], in Manifestoes of Surrealism, transl. R. Seaver and H.R. Lane, Ann Arbor 2007, pp.117–87, at p.125. footnote 1

- Donald Trump: ‘I could shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose any voters’, The Guardian (24th January 2016), available at www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jan/24/donald-trump-says-he-could-shoot-somebody-and-still-not-lose-voters, accessed 27th September 2023. footnote 2

- P. Pomerantsev: ‘The hidden author of Putinism: how Vladislav Surkov invented the new Russia’, The Atlantic (7th November 2014), available at www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/11/hidden-author-putinism-russia-vladislav-surkov/382489/, accessed 27th September 2023. footnote 3

- See also L. Abse Gogarty: ‘The art right’, Art Monthly 405 (April 2017), available at www.artmonthly.co.uk/magazine/site/article/the-art-right-by-larne-abse-gogarty-april-2017, accessed 27th September 2023. footnote 4

- See F. Jameson: Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, London 1991, esp. p.53. footnote 5