Mixing fiction and reality: the parafictional history of Dora Longo Bahia’s ‘Do Campo a Cidade’ (2010)

by Corey Dzenko • June 2021

‘All historians, whatever else their objectives, are engaged in this process [of institutionalising histories] inasmuch as they contributed, consciously or not, to the creation, dismantling and restructuring of images of the past which belong not only to the world of specialist investigation but to the public sphere of man as a political being’. Eric Hobsbawm1

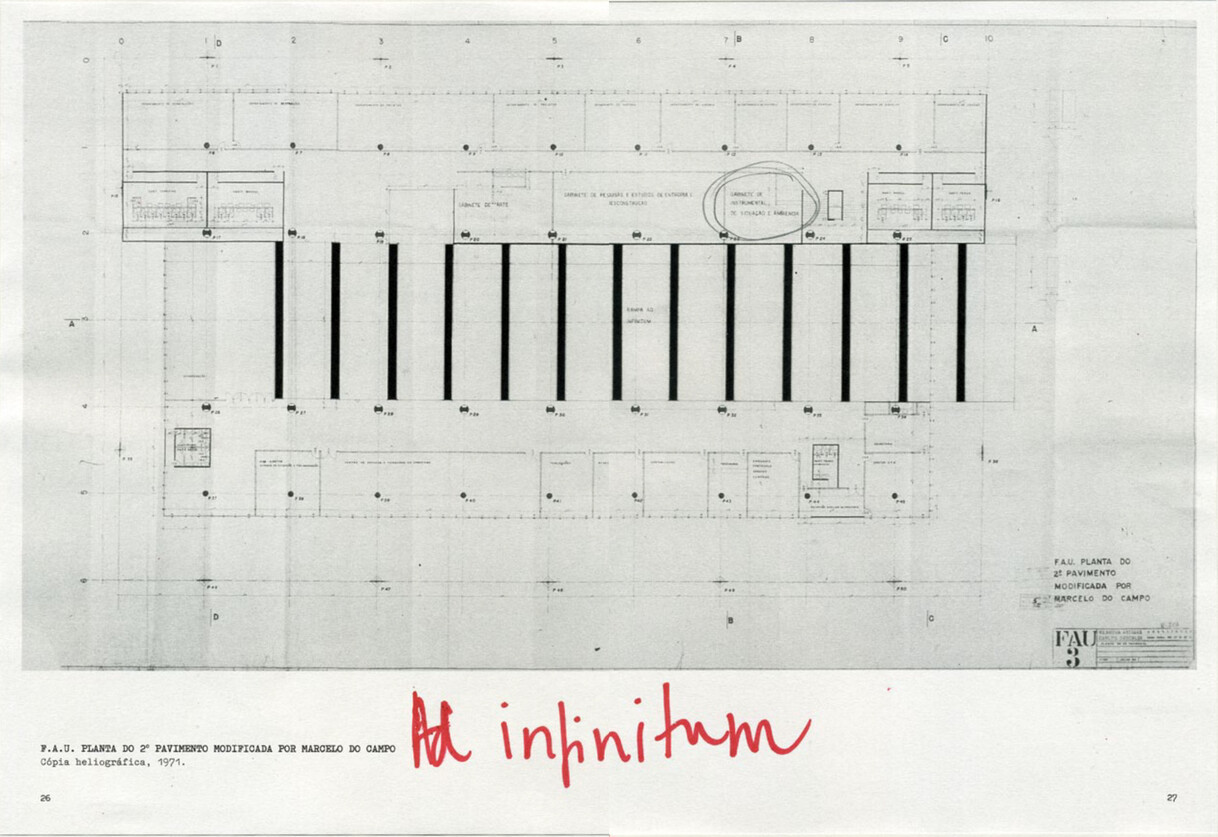

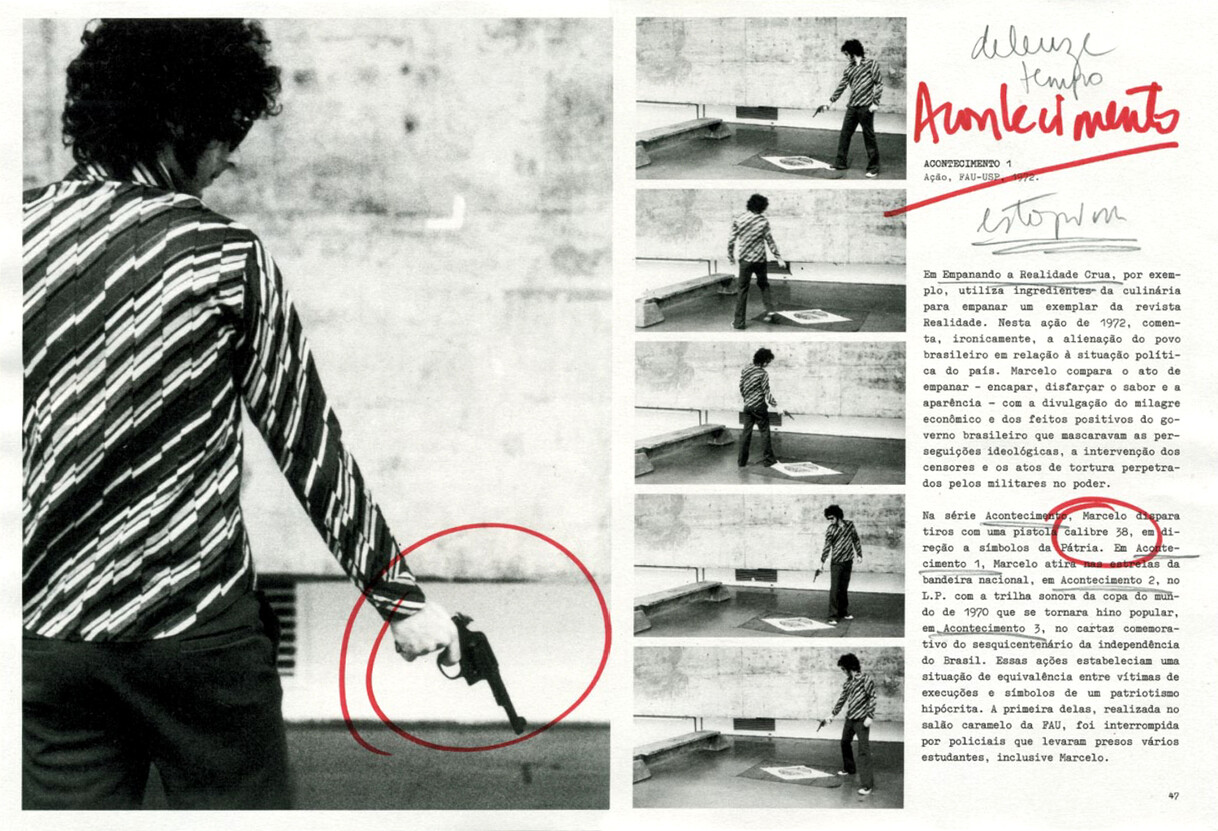

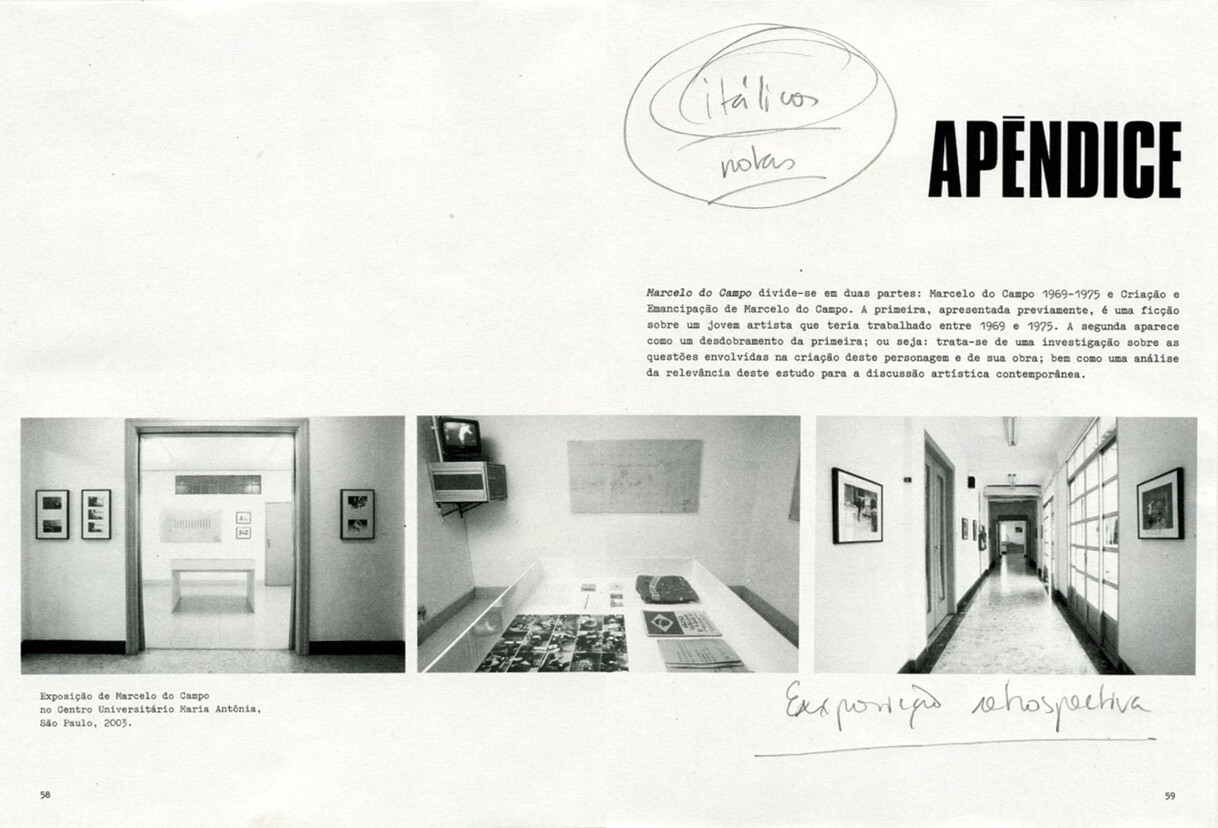

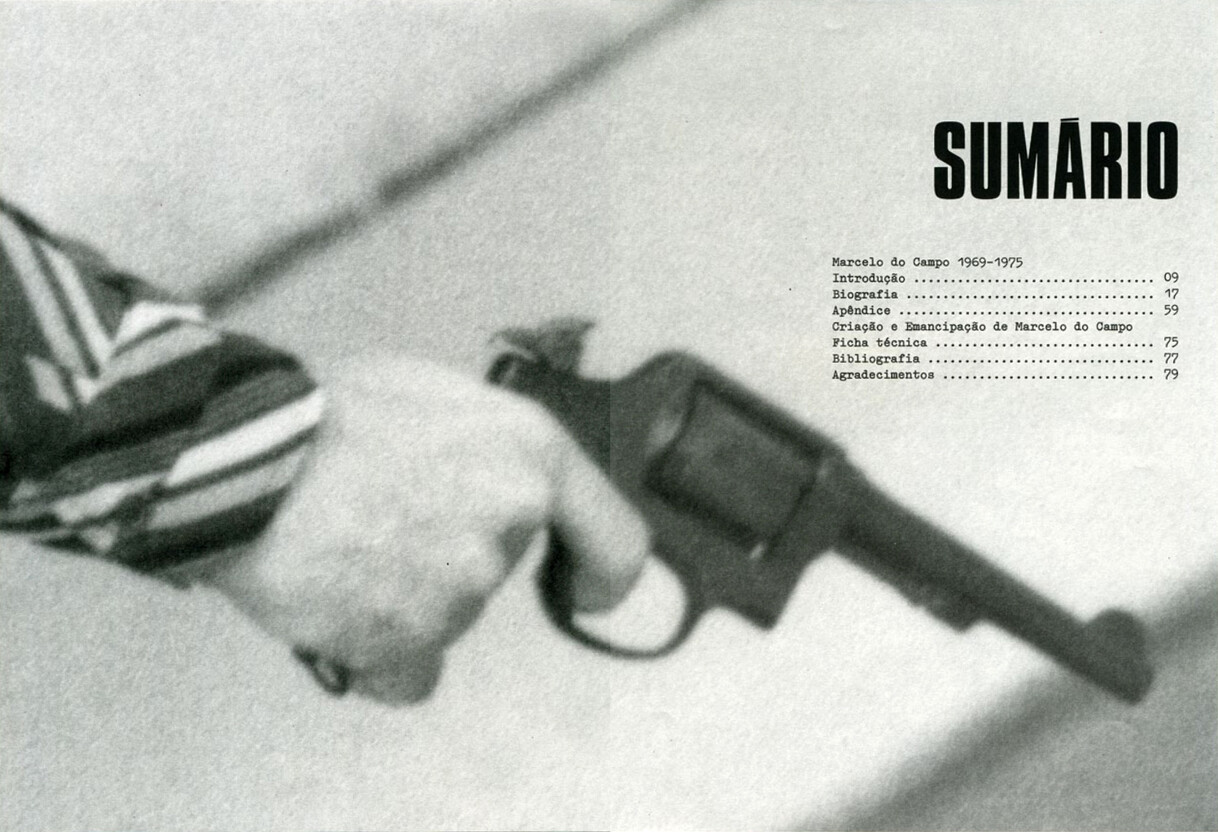

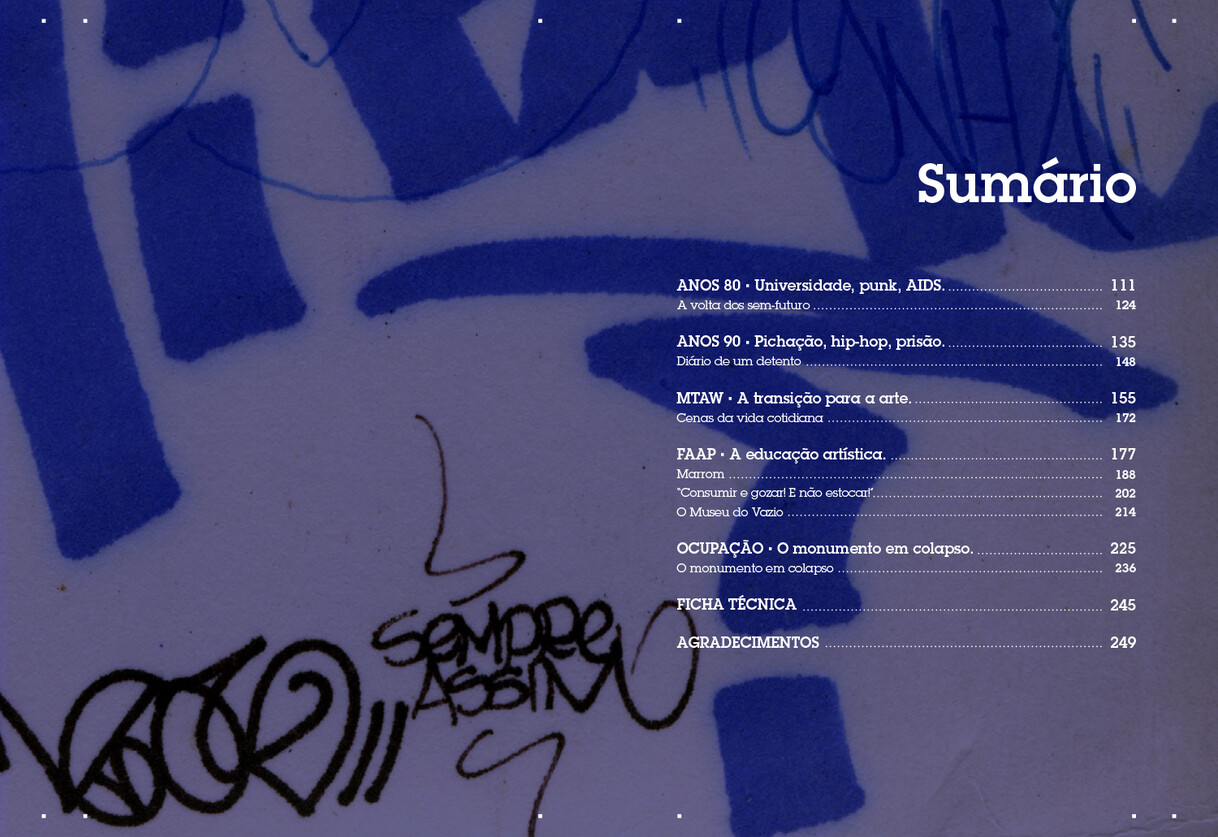

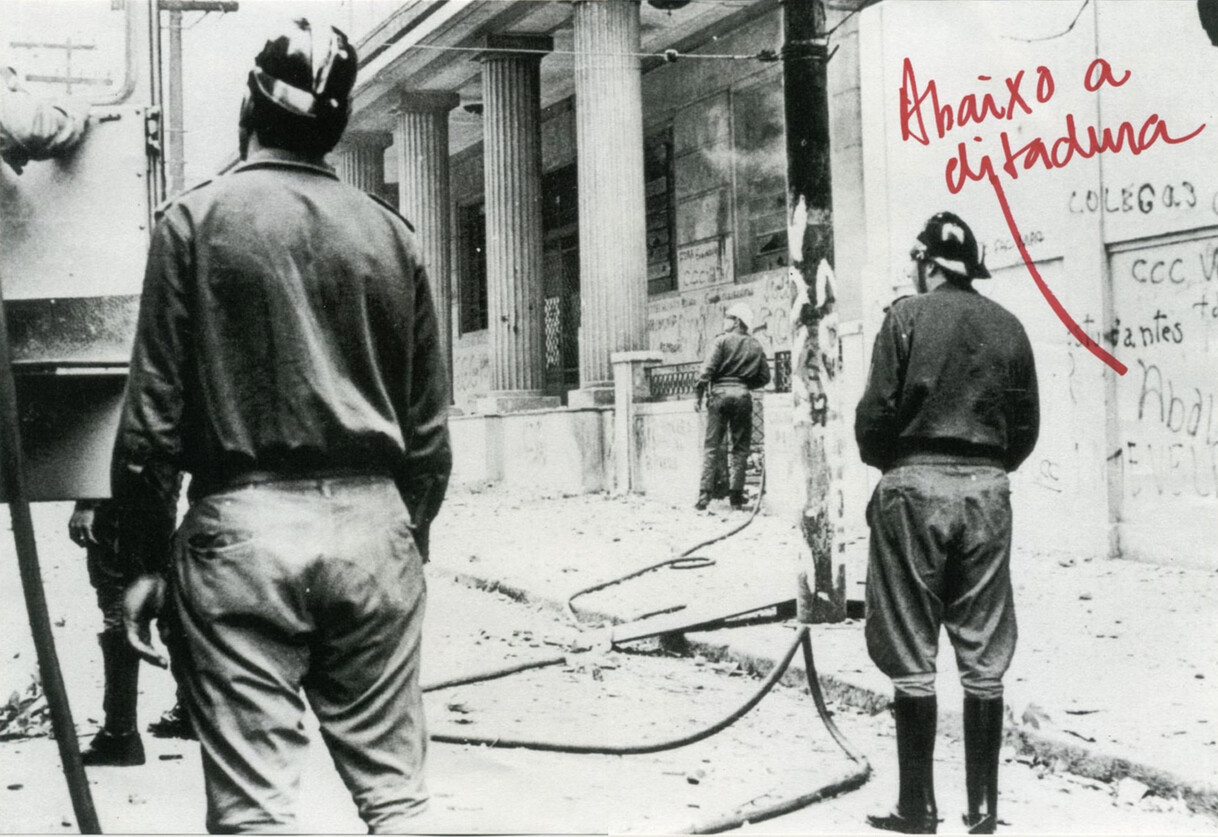

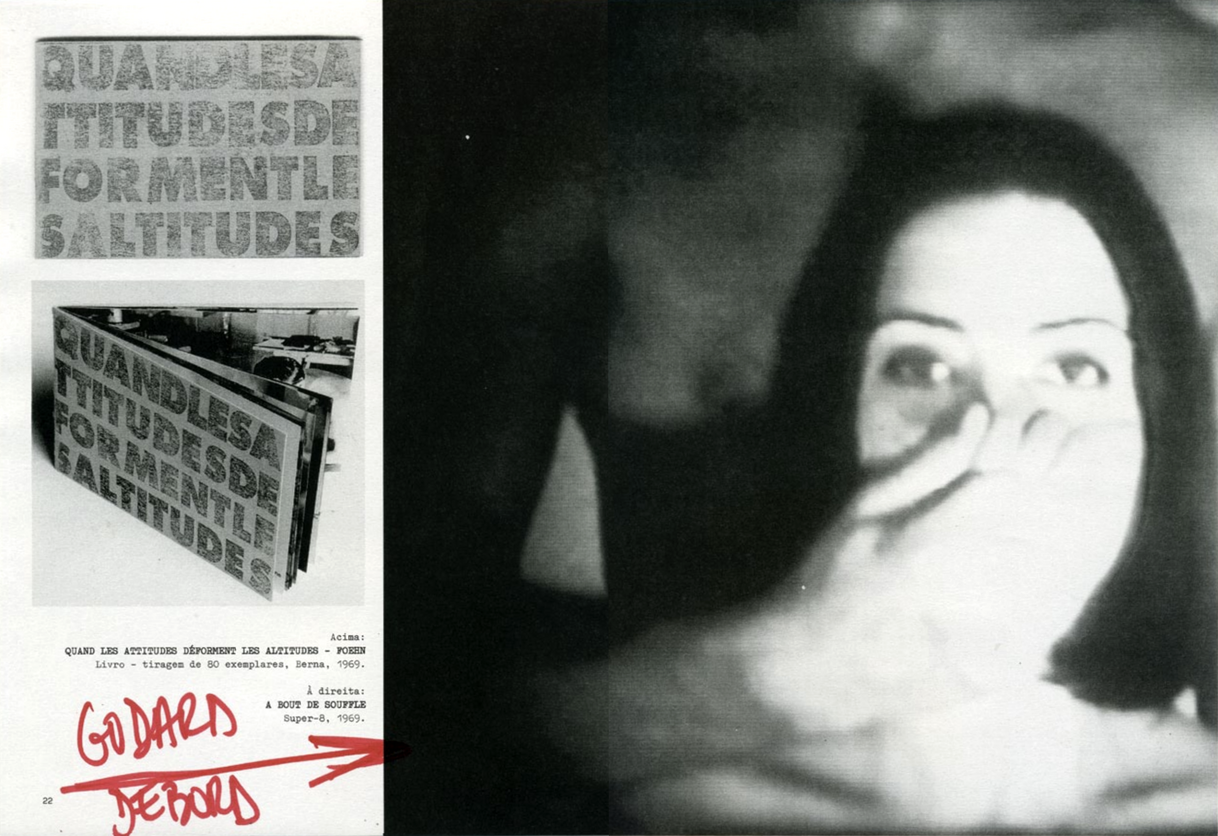

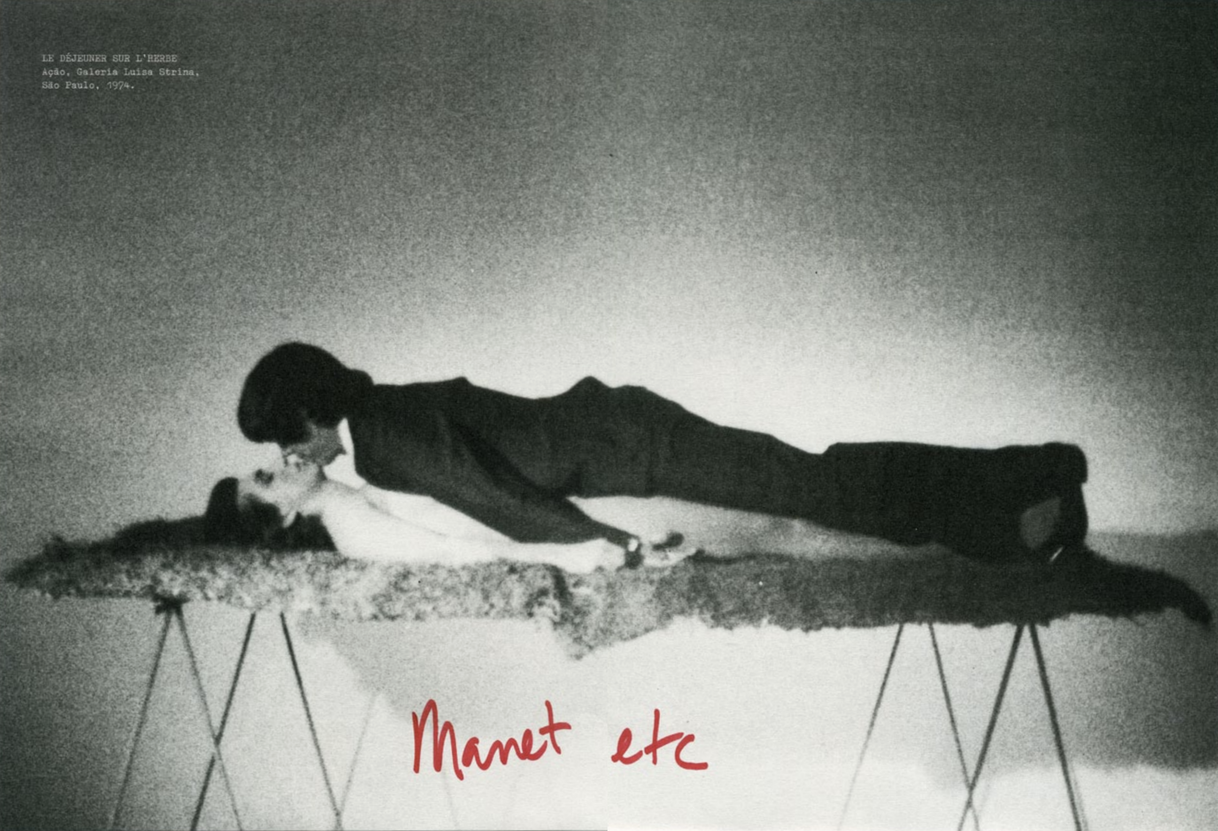

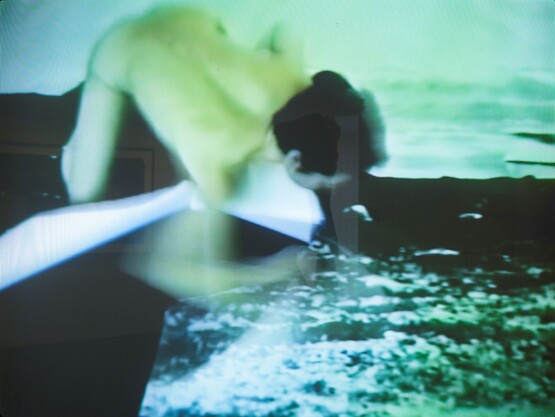

While undertaking research for her MA thesis in Visual Poetics at the School of Communications and Art, University of São Paulo (USP), the Brazilian multimedia artist Dora Longo Bahia (b.1961) claimed to have unearthed archival materials about the biography and practice of an artist named Marcelo do Campo. As Longo Bahia recounted, do Campo was born in São Paulo in 1951 and created art from the late 1960s to 1975. To fulfill her degree requirements, in 2003 Longo Bahia organised an exhibition to display the fragments of do Campo’s projects she had access to: theoretical drawings, in which he disrupted plans of modernist architectural buildings to the point that they would collapse if built according to his modifications FIG. 1; photographs and artefacts from his performances FIG. 2 FIG. 3; and clips from his Super-8 films. In a 2006 monograph on the artist based on her MA thesis, Longo Bahia published images from do Campo’s projects along with essays that she had written, underscoring that do Campo used art to critique social structures and cultural institutions of his time and place.2

In 2010, for her doctoral dissertation in the same Visual Poetics programme, Longo Bahia chronicled a more recent Paulistano artist, Marcelo Cidade, who was born in 1979 and made art until 2007. In an unpublished catalogue devoted to the artist and submitted as part of her PhD, Longo Bahia explained that Cidade challenged numerous institutions, using graffiti, social interventions and performance as his media of choice. For instance, frustrated by his university’s monitoring of students, he attacked ‘the alleged vigilance of the establishment, parodying its protected space, full of authoritarian and groundless rules’ by bringing bricks into a classroom over the course of months.3 One weekend he used these bricks to install a wall behind a doorway, escaping out of the window on Sunday. Students and faculty found his barricade when they returned the next day, while Cidade joined them in anonymity to watch their reactions FIG. 4. Longo Bahia collected these two artists’ histories into her almost three-hundred-page long dissertation, ‘Do Campo a Cidade’ – a reference to the two Marcelos that also translates as ‘from the countryside to city’. By presenting the two artists together, Longo Bahia’s dissertation invites an extended comparative analysis as she situates them among the histories of art and Brazil, along with transnational events.

In reality, both artists were invented by Longo Bahia as fictional heteronyms, using the term as defined by the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935): ‘an imaginary author with characteristics and tendencies remarkably different from those of its creator’.4 She fabricated both Marcelos, their works of art and the archival documentation she ‘recovered’ concerning the two artists who share a first name. According to the historian Eric Hobsbawm, ‘the history which became part of the fund of knowledge or the ideology of nation, state or movement is not what has actually been preserved in popular memory, but what has been selected, written, pictured, popularized and institutionalized by those who function it is to do so’.5 As a doctoral candidate Longo Bahia had the institutional authority to write a history by curating and publishing her findings. As an artist she took the latitude to work more creatively with the historical materials she ‘found’.

Longo Bahia’s dissertation functions as an art object within her larger œuvre as well as a textual document. As a ‘book-object’ or ‘text-image’, it ‘eliminate[s] the gap between practice and theory, between the making of art and its academic investigation. In this way, it aims to meet the demands of the Visual Poetics field that favours both theoretical and experimental researches about the artistic process’.6 Longo Bahia matched the visual styles of her two catalogues to their specific historical contexts, lending them an air of accuracy. Black-and-white photographs and film stills identify do Campo as a more historical artist FIG. 5 than Cidade, whose use of graffiti and brightly coloured graphics situate him in more recent decades FIG. 6. Together the Marcelos offer opportunities to examine Longo Bahia’s various stated interests that include questions of authorship; relationships between documentation and art; the way the ‘art world’ subsumes forms of art that initially challenge it; and broader global economic inequalities.

The history of art that Longo Bahia recounts is not conversant with non-European forms, as her citations rely on the specificity of elite cultural institutions within and beyond Brazil. The present article begins to untangle fact and fiction, showcasing the critical value of Longo Bahia’s narrative. By working both historically and contemporarily toward the believable ‘parafiction’ she created, Longo Bahia offers a performative project that allows viewers to experience history – specifically art history – as an intertwining of agents and institutions amid relationally constructed power dynamics.7 These dynamics include, but are not limited to, those of gender and of Brazil in relation to the European art world. Thus, Longo Bahia’s readers, or viewers, must navigate many facts and fictions, participating in her constructed narration of history. For if they miss the fact that the biographies are fictional, then Longo Bahia’s history may become just another record of male artists from the past. Given that she has convincingly presented her fictions within factual historical contexts, it takes more than a cursory glance for viewers to notice the deception. However, if they engage with Longo Bahia’s strategic intent, they arrive at a radical decolonial and anti-patriarchal history, one which dismantles many prevalent and ongoing narratives of art history that continue uncritically to prioritise male, European and European-American artists.8

Fictionalising critical histories

Longo Bahia’s decision to fabricate a male trajectory for do Campo’s history was an attempt to challenge the frequent interpretation of art made by women artists as inherently ‘feminine’ and part of ‘an abstract women’s universe’.9 As one of many examples, she cites the way the New York City-based art critic Barry Schwabsky described the work of the Brazilian painter Beatriz Milhazes as ‘a traditionally feminine form of piety’ and the artist as fascinated by ‘feminine ornaments – laces, embroidery, flounces and ribbons’. To show how critics and historians similarly tend to overidentify artists of colour in terms of race, Longo Bahia cites the book Artoday (1995), which categorises the New York City-based African American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat in the section ‘Racial Minorities’, but considers the white artists Julian Schnabel, Eric Fischl, Kenny Scharf and David Salle as the more generalised ‘New Art in New York’.10 When Longo Bahia eventually reveals her deceit, she draws attention to her role as historian. But her audience must navigate Marcelo’s fictions if they want to clear a path that begins to expose the facts of Dora herself. At the same time she disrupts any tendency to read her work solely as a feminist or institutional critique. As this article will expand upon, Longo Bahia appropriated many works of art by numerous artists who each worked from their own subject position, along with their relationship to the art world and other institutions of power. Taken as a whole, Longo Bahia brought all of this material together. But her authorship gives way, in part, to the perspectives of the other artists included. Assigning the impact of Longo Bahia's Marcelos to a singular critique limits the project's possibilities. Such complexity is apparent with do Campo’s catalogue and even more so once Longo Bahia added Cidade to her narrative and analysis.

Longo Bahia included Cidade to form a parallax between the two men.11 She situated do Campo’s practice amid the military dictatorship in Brazil, bookending his artmaking with the protests of the late 1960s and the global recession of 1975. She located Cidade’s history a few decades later. He grew up in the punk scene of the 1980s, participated in 1990s hip hop and graffiti and worked during the aftermath of the 2001 attacks on New York City’s World Trade Center. Consequently, the Marcelos are shown to be determined by the ‘cultural and political revolutions of 1968 and 09/11’ respectively.12 Furthermore, as she suggested in the prologue to her project, economic analysis permeates Longo Bahia’s dissertation, such that do Campo serves as ‘the naive artist, who in the mid-twentieth century believed he was able to subvert the art/market relationship and to act aside of it, evidencing the inter-relationship between art and political action’.13 After the emergence of the simulacrum – the term Jean Baudrillard uses to theorise that human existence has become a simulation of reality as symbols and signs have replaced reality and meaning – ‘Cidade is the unsatisfied artist who tries to subvert the friendly relationship between art and the power represented by the market in a society that is imprisoned in an eternal present that continuously consumes itself’.14 Thus the two Marcelos undertake their artistic interventions, both situated within the cultural upheavals and the economic systems of their times. But just enough time separates the two men to mean that they work within different theoretical models in relation to power, reality, the market and the changes that may – or may not – be possible for them to bring about.

To bring the Marcelos into being Longo Bahia interwove fact and fiction. In 2009 the art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty defined this method of artmaking as parafiction, a term that finds a parallel in paramedics. Such medical professionals are ‘like’, but not, medical doctors; similarly, parafiction is related to, but not quite, fiction. Lambert-Beatty wrote, ‘parafictional strategies are orientated less towards the disappearance of the real than towards the pragmatics of trust. Simply put, with various degrees of success, for various durations, and for various purposes, these fictions are experienced as fact’.15 Lambert-Beatty continues, ‘Parafictions in general are performative, where that is understood to mean that they effect or produce something rather than describe or denote it’.16 She lists a number of artists working in this way, including the Yes Men, Walid Raad and Eva and Franco Mattes. To this list, we can add Longo Bahia.

Rather than writing a history, through parafiction Longo Bahia produces the experience of history for her viewers. To help make her project seem trustworthy she used visual languages related to the two men’s historical contexts. Her 2003 exhibition about do Campo employed the traditional museological practice of displaying documents in glass vitrines and hanging additional materials on the walls. She also developed an artist website to bring her first heteronym to a larger audience.17 In addition, the USP’s online repository ‘Teses e Dissertações’ (Theses and Dissertations), stores Longo Bahia’s dissertation like it would any other. All of these decisions present the histories of the Marcelos in formats expected of historical studies, providing additional institutional weight and making them more believable.

In the final form of her project, Longo Bahia does not shy away from the fact that her relatively believable histories are based on fiction. In the acknowledgments at the end of do Campo’s 2006 catalogue, she reveals that her MA degree thesis committee convinced her to openly admit she had invented the historical artist. Her 2006 catalogue includes an essay explicitly titled ‘The creation and emancipation of Marcelo do Campo’, and she laced material from this essay throughout her PhD dissertation in 2010. She also added various handwritten notations to do Campo’s catalogue that she included in her dissertation FIG. 7.

The technical credits in both of her catalogues list the makers of the works she curated into the artists’ portfolios and when. For example, Longo Bahia made and appears in some of do Campo’s films, which in reality date from 2000 to 2001, not the late 1960s and early 1970s as suggested by their captions. The technical credits for Cidade’s projects similarly list many contributors, including multiple entries for ‘Marcelo Cidade’. But why does a fictional artist deserve credit for actual works of art? Longo Bahia explained:

Marcelo Cidade is a fiction but his name and part of his work was appropriated from ‘a real artist’ who was my student in the Fine Arts School–FAAP [Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado . . .] I stole his name and part of his life and work. Both Marcelos Cidade were born in the same year and in the same city but their stories differ a lot. All the works attributed to Marcelo Cidade (the fictitious one) are appropriated from my students at FAAP, some from the real Cidade, some from his fellow students.18

In the acknowledgments of her MA thesis, Longo Bahia thanked ‘all of those who, like myself, mix fiction and reality and believe in lies, making them come true’.19 And yet, in a seemingly purposeful contradiction, the very last page of her dissertation ends, ‘This is a fiction. Any resemblance with places, facts and known people are just coincidence’.20

Historicising critical fictions

Although Longo Bahia’s project contains many fictions, presenting them as varying degrees of fact as a parafiction encourages an examination of larger practices of history. For instance, a common marker in telling the histories of artists from Latin America is that they often connect their artmaking to Europe. Historically this included studying in the academy, which promoted ideals modelled after European institutions, studying with a European artist who visited their region or with a local artist who had trained in Europe. Histories of artists from Latin America frequently highlight their European training as a way to seemingly legitimise their work. Such practices are rooted in the tradition of the Grand Tour, but often continue today.

In ‘Do Campo a Cidade’ Longo Bahia alludes to the exchanges between Latin America and Europe in a number of ways. Specific references to Brazil occur throughout the history of the Marcelos: the aforementioned criticism about the painter Beatriz Milhazes; do Campo’s time spent studying under the modernist architect João Batista Vilanova Artigas at USP; Cidade’s affiliation with a crew of pichadores, or taggers, in São Paulo; and passing remarks about the artists Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark. Allusions to artists and architects from Europe and the United States are more explicit in Longo Bahia’s use of titles and appropriation of works of art. She refers to many more Europeans than Brazilians in the artworks discussed in her catalogues, including Marcel Duchamp, Jean-Luc Godard, Edouard Manet, Robert Smithson, Le Corbusier, Andy Warhol and Basquiat. By plagiarising titles of canonical artworks and reworking their content, Longo Bahia takes credit for others’ work while offering a comment on the reliance on European narratives and histories, overall, subverting the European, male authorship of many such pieces.

Longo Bahia also weaves connections between Brazil and Europe into the Marcelos’ biographies. For example, before enrolling at USP, do Campo produced art collaboratively in Switzerland. His father was a journalist and moved abroad, providing the initial impetus for the artist to move to Europe. While in Switzerland he lived with other artists, founded the artist collective Front Ordinaire pour une Esthétique Helvétique Neutre (FOEHN), and began to examine power dynamics in his own art. After a short while, do Campo returned to Brazil and enrolled at USP.

Longo Bahia placed Cidade’s youth within the punk subculture of the 1980s, which was to heavily influence his later artistic output. His parents participated in the punk scene of São Paulo, however, Longo Bahia is careful not to homogenise the transnational genre. Longo Bahia herself was, and still is, a bassist in many post-punk and noise bands, including Disk-Putas, Verafisher, Maradonna, Sujos de Dora, Blá Blá Blá and Cão. As both a historian of and an active participant in punk she explained, ‘for the English scene, punk was a criticism of the capitalist world, the consumerist society, as it represented the cultural boredom and the social decay of the industrial suburbs. For us here in the “third world”, without any great cultural and financial resources, it was the endorsement for the projection of the poor and rough present’.21 Furthermore, it was difficult for the suburban youth of São Paulo’s punk scene ‘to accept the tropicalist myth of the optimistic nation. They did not coexist with Brazil’s national beauty, they did not have a traditional folklore to be proud of, and they did not fit in with the regionalist demands of other Brazilian cities. They took the metro or the bus to go to the record stores to trade stickers at the centre of a gloomy and graceless city’.22 Longo Bahia’s comparison between the history of punk in England and Brazil recognises the particularity of historical contexts when striving to understand forms – such as punk – that reach beyond regional or national bounds as worldwide phenomenon. Thus, Cidade's biography as told by Longo Bahia reminds her readers of this as well.

Citing the French avant-garde

In 2012, after Longo Bahia’s graduation, Yiftah Peled – another student in the same graduate programme as Longo Bahia – published an article about Visual Poetics methodologies with examples from USP and the University of Rio de Janeiro. One method he discussed is the blurring of fact and fiction, using Longo Bahia’s creation of do Campo as a model for such practice. Peled recalled Longo Bahia’s understanding of every work of art as ‘a state of suspension between reality and its representation’, and described her narrative about do Campo as ‘a chink of representation of scientific text that is allowed by the area of Visual Poetics. The foundation of a supposed scientific truth is manipulated’.23 More broadly, for Peled, Visual Poetics allows ‘for a performative platform, a structured context for research and an expectation for creative superation of formerly established rules’.24 Peled positioned the Dadaist Marcel Duchamp as a precedent for contemporary Visual Poetics because ‘the insertion of ready-mades is contextually and discursive[ly sic]-based, which is important for the art production that followed and for its relationship towards performatives’.25 Like Peled, Lambert-Beatty described parafiction as performative and identified Duchamp as a possible precedent, writing, ‘Of course, Marcel Duchamp lurks behind all of these examples, and whether or how this recent work reimagines his legacy is an open question’.26 Yet Peled does not mention Lambert-Beatty’s article, and because Lambert-Beatty does not address practices outside of Europe and the United States, she does not incorporate Visual Poetics from Brazil into her examination of parafiction. Longo Bahia’s project helps us connect them, as artists often work across national and hemispheric bounds, and because her iconoclasm plays with many historical references with great freedom to conceptual and performative ends.

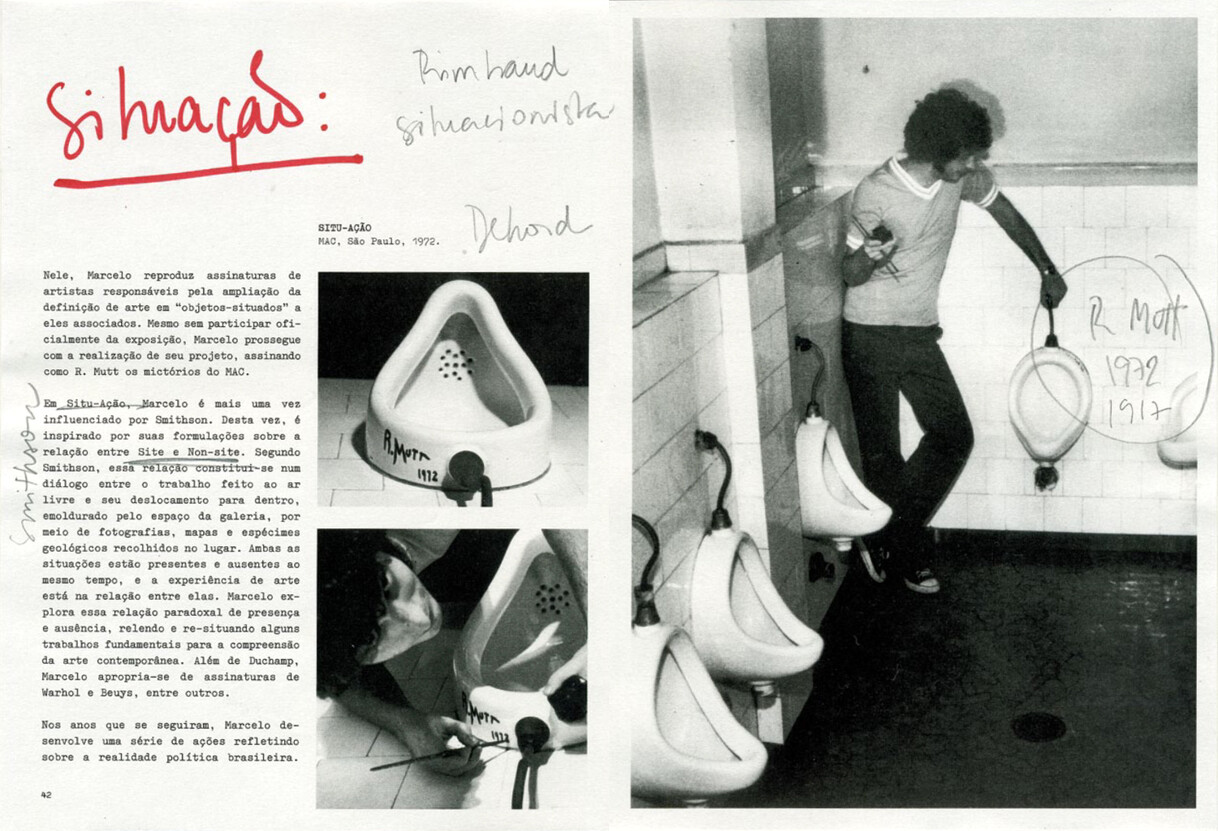

Whereas Longo Bahia’s methodology, which grounded her Visual Poetics programme, is a nod to Duchamp, her histories of the Marcelos also contain explicit references to the Dadaist. To start, the use of ‘do Campo’ as a last name echoes Duchamp’s surname. Then there is also the time when do Campo updated the iconic readymade Fountain (1917). In Longo Bahia’s history, do Campo proposed a project for the actual 1972 exhibition Jovem Arte Contemporânea (Young Contemporary Art) at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo. Although not selected to exhibit, photographs in Longo Bahia’s catalogue show that do Campo intervened in the institution anyway. He signed the museum’s urinals with the signature seen on Duchamp’s historical readymade, ‘R. Mutt’, but also inscribed the urinals with his own date, 1972 FIG. 8. This causes the piece to exist simultaneously in multiple temporalities: the past era of Duchamp, the later twentieth century of do Campo and the twenty-first century of Longo Bahia’s project. In addition, it also crosses another type of boundary often found in art historical studies, that of geographies. Duchamp had moved from France to New York City. There he helped found the Society of Independent Artists in 1916, the group who would later refuse to display Fountain. At the time, commentators remarked that artists in the United States should celebrate what the nation was good at, rather than maintaining an inferiority complex with regard to the European continent.27 Do Campo then reworked the piece in São Paulo, connecting it to the ‘third world’ city and establishing consideration of a possible power dynamic between France, the United States and Brazil.

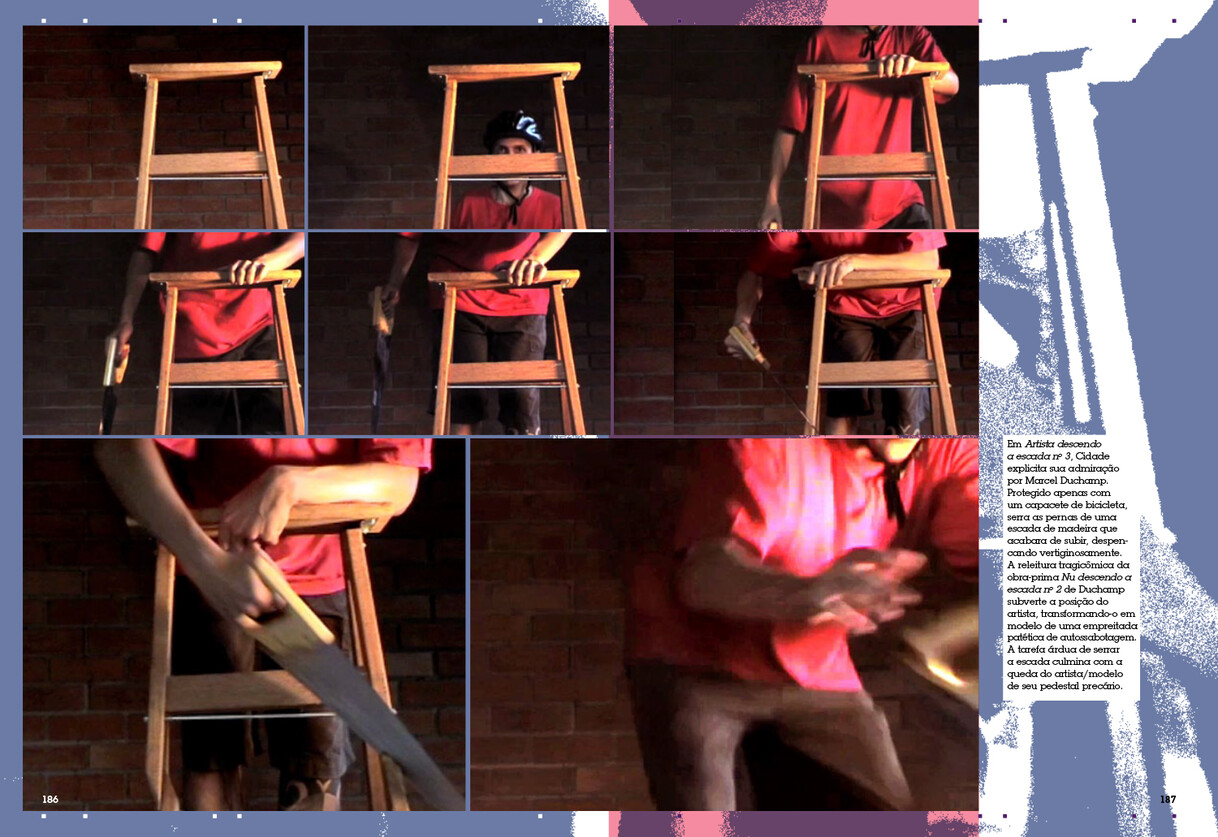

Similarly, Cidade’s undated performance Artista descendo a escada n° 3 (Artist descending a staircase n° 3) appropriates the motion in Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912; Philadelphia Museum of Art). Rather than merely copy the downward movement of Duchamp’s painting, Cidade attempted to ascend a ladder FIG. 9. However, in an act of self-sabotage he sawed the legs off the ladder while climbing it. In Longo Bahia’s narrative, this destructive act caused him to fall from the celebrated heroic position of the artist. As a result, the piece challenges the motif of the genius or hero artist and is a moment of critical intervention into patriarchal tellings of art history.

In addition to bringing Duchamp to mind, do Campo’s first film, A bout de Souffle (Breathless), references Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 film of the same title. In do Campo’s version a man grasps the nose and mouth of a woman FIG. 10. He takes her breath away, yet she maintains power; every time she shakes her head, he lets her go.28 Do Campo’s last known work is the performance Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the grass), which is modelled on Manet’s painting (1863; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) FIG. 11. For this performance, do Campo walked through a gallery to a supine woman on a table covered in grass. The seemingly more powerful – clothed and male – do Campo tried to lie on top of the nude woman FIG. 12. In a ridiculous, unexpected act, he licked her like a domestic pet.29 Through her description, Longo Bahia discursively constructs his act as a subversion of stereotypical gendered power; the supine woman becomes the pet’s master or owner as he feebly attempts to retain his balance on the uneven surface of her body.30

It is telling that not only does Longo Bahia cite the likes of Duchamp, Godard and Manet as influences on do Campo and Cidade, but she has their names and their art make direct references to them. These three male artists worked outside of the institutional norms of their times. By allying the art of the fictional Marcelos and, thus, her own, with the once controversial but now canonical Duchamp, Godard and Manet, Longo Bahia theoretically interjects both Marcelos, as well as herself, and their various challenges to convention into the often-limited canon, subverting and expanding it against the relentless colonial and patriarchal gatekeeping of the Western art world.

The ongoing performativity of history

Although Longo Bahia has admitted her role in creating her fictional Marcelos, her histories continue to unfold. For example, she granted the present author permission to reproduce pages from her dissertation for another publication,31 but she requested, ‘Please do send me copies of the article as we are all very curious (me and [the] Marcelos) about it’.32 The performativity of Longo Bahia’s parafiction continues.

Do Campo resurfaced more recently. Longo Bahia’s 2006 catalogue and 2010 dissertation claim that no one had heard about do Campo’s whereabouts since 1975 when he retreated to the Brazilian coastal town of Florianópolis to surf and keep bees. However, in his analysis of Visual Poetics, Peled referenced a 2011 exhibition held at the Contemporão Espaço de Performance. The postcard announcement for the exhibition includes a picture of the beach along with yellow hexagons suggestive of beehives. According to the exhibition’s text panel, the whereabouts of do Campo was discovered, and, ‘it is important to know that the artist changed his name and became known as Marcelinho Campeche. Despite his time devoted to surfing and to bees, Marcelinho continued to produce artistically and many of his works were made in collaboration with other local artists and performers’.33 Marcelinho is a diminutive of Marcelo that can be used as an endearment, whereas Campeche refers to a beach and island in the area. The fictional artist has transformed, roughly, from Marcelo of the fields to little Marcelo of the beach. The artists Campeche supposedly collaborated with are listed on the exhibition’s postcard and include Peled, who curated the project.34 In this case, Longo Bahia did not help to organise the exhibition and never even saw it. Thus, do Campo continued to live his life, but as Campeche and without Longo Bahia.

For Cidade, Longo Bahia appropriated the name of one of her students, who has continued to make art and, according to Longo Bahia, was very supportive of his teacher’s invented history.35 His continued artistic output differs from that of the fictional Cidade FIG. 13. As Longo Bahia explained, after various disciplinary actions by the university, her heteronym became homeless to wander the ‘urban jungle’. In debt to his surname and city, he felt his ‘mission’ was to ‘spread the true sense of art’; he believed he could do so only outside of the academic confines of art school.36 Similar to do Campo’s story, Longo Bahia does not provide her audience with a definitive end to Cidade's; there has been no news about him since he moved to the streets.

Because of this, confusion can arise between the fictional Marcelo Cidade and the real-life Marcelo Cidade. Around the same time that Tate Modern was acquiring one of the latter’s artworks,37 an announcement appeared of a lecture by Cidade to be held at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) in April 2014. Neither SFAI’s event listing nor Tate’s collection file make mention of Longo Bahia, so it can be understood that this is Longo Bahia’s student, not her heteronym. Such ongoing references, the availability of the fictional do Campo’s website and the online presence of the actual Cidade mean that while Longo Bahia may have completed her graduate studies, the histories of the artists she addressed for her degrees continue. Additional details from the artists’s entwined histories may yet surface, to be untangled by viewers and researchers.

Longo Bahia consciously moulded history as an artistic medium to create the performative parafiction of ‘Do Campo a Cidade’. She guides her audience through a reflexive analysis of history, one which occurs only as a result of her mixing of fiction into reality. Her project counters Eurocentric histories without denying the interactions that take place between artists in Latin America and Europe. In our contemporary moment of study, many scholars are re-examining the discipline of art history in terms of its institutional biases. Longo Bahia’s transnational parafiction thoughtfully enacts these more recent critical approaches while she, as an iconoclast, works from a confidence that does not deny the contributions of many of art’s ‘great’ European fathers, but also does not allow them to remain sacrosanct in their positions in art history.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dora Longo Bahia for her thought-provoking art and conversations; Theresa Avila and Gay Falk for their feedback on drafts of this essay; Karen Sniquer and Jefferson Filgueiras for translating portions of Longo Bahia’s dissertation; and this journal’s reviewers for their support and helpful suggestions. This article is dedicated to the memory of David Craven, who introduced me to Longo Bahia’s art and encouraged me to write about it.