Lucian Freud’s sketchbooks: drawings from life

by Tanya Bentley • June 2023. In collaboration with Drawing Room, London • Journal article

Lucian Freud (1922–2011) is known today as one of the foremost figurative painters of the twentieth century. However, when Freud was emerging as an artist in the late 1930s and 1940s, his primary preoccupation was drawing. Reflecting on this period, he said: ‘I would have thought I did 200 drawings to every painting in those early days. I very much prided myself on my drawing’.1 In the vast scholarship on Freud, it has often been said that he abruptly stopped drawing in the late 1950s to give space to the developments in his paintings, which were shifting away from linear and tight brushwork to a more expressive and broadly painted style.2 Yet, to describe Freud’s artistic journey in this way overlooks his continued use of sketchbooks, the majority of which are now held in the archive of the National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG). They span his entire career, from his days as a student at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing (1939–41) and his formative travels across Europe in the late 1940s, to the decades of increasing recognition and fame that followed. There are drawings that relate to now well-known paintings and etchings together with studies of his many committed sitters, including his children, his lovers, art world associates and his beloved pets. It is clear from this resource that, alongside his paintings, drawing continued to be an integral mode of expression for Freud, even if it was predominately something he did for himself and not for public exhibition.

The NPG was allocated forty-seven of Freud’s sketchbooks in 2015 through the Arts Council England Acceptance-in-Lieu scheme. The total number of the artist’s sketchbooks is yet to be determined. In addition to these sketchbooks the NPG also received a vast treasure trove of letters from the Freud family, including childhood letters between Lucian and his paternal grandparents, Sigmund and Martha, and his parents Ernst and Lucie. They reveal the family’s story of migration from Germany to the United Kingdom in 1933, triggered by Hitler’s rise to power. There are also over one hundred coloured pencil and crayon drawings, made when Lucian was between just five and eight years old and kept in almost perfect condition by his mother, who always nurtured his creative talents; she brought all these drawings with her to England. As a result of these acquisitions, the NPG owns the largest collection of Freud’s drawings in public hands. It forms an intimate archive of his practice.

In 2017–18 the sketchbooks were catalogued and digitised, allowing the public to browse them at their leisure. In 2021 a generous grant from Getty through its Paper Project allowed the present author and a number of colleagues at the NPG to start the process of resolving some of the sketchbooks’ physical issues and, where possible, date and identify sitters. Most of the funding was allocated to conservation work. This has enabled conservators to stabilise the bindings so that the sketchbooks can be safely put on display. Careful analysis of the drawings by paper conservators has provided rich insights into the different media Freud used and the types of paper he favoured. To allow for further exploration of the sketchbooks and the wider Freud archive, some of the funding from Getty has been used to create a gallery at the NPG dedicated to the Lucian Freud Archive, open from June 2023.

Freud’s sketchbooks were part of the fabric of his studio and were not treated with the cautious respect that museum curators and conservators afford them today. Instead, they carry the traces of a productive artist: they are well-worn, pages are stuck together, the covers are splattered in paint, there are ink and coffee stains, spines have come away from the bindings and in a couple of cases there is evidence of vermin infestation, with indications of teeth marks on the books’ corners. The French painter Françoise Gilot (1921–2023), who is also known for her relationship with Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), once wrote an essay about Picasso’s sketchbooks, which she titled ‘Enigmas for posterity’.3 This description also rings true for Freud’s sketchbooks. Freud did not date them, nor did he use them in any sequential order. He would turn to a page at random or, in some cases, would find a sketchbook from years earlier and start to populate the pages again in a different orientation. Drawings have been torn out, given to friends or sold on. Therefore, it is difficult accurately to chart his creative process in a linear way.

When surveying the sketchbooks, their substantial differences in scale are immediately apparent. One might assume that this variety would correlate in some way to their purpose: the pocket-sized sketchbooks being used by Freud to make quick sketches as he went about his daily life, whereas the larger ones were used in the studio as preparatory tools for finished paintings. However, this is not the case. The smallest sketchbook in the archive, no.9, has a series of intricately drawn portrait heads of sitters who came to his studio, such as Jacquetta Eliot, Countess of St Germans (b.1943). In contrast, one of the largest, sketchbook no.6, travelled with Freud to France in the late 1940s. This volume was originally an English accounts ledger dating from the 1780s; faint writing in iron-gall ink is visible throughout the first half of it. This forms the backdrop to quick sketches of Freud’s view from his balcony at the Hôtel Welcome, in the old port of Villefranche-sur-Mer, in the south of France, where he stayed during the winter of 1948–49 FIG. 1. Freud had found the book in a local market while staying with the textile designer and painter EQ Nicholson (1908–92) at Alderholt Mill, on the Hampshire–Dorset border, during the Second World War.4 He may have chosen to repurpose the ledger because of the shortage of high-quality paper during and after the war.

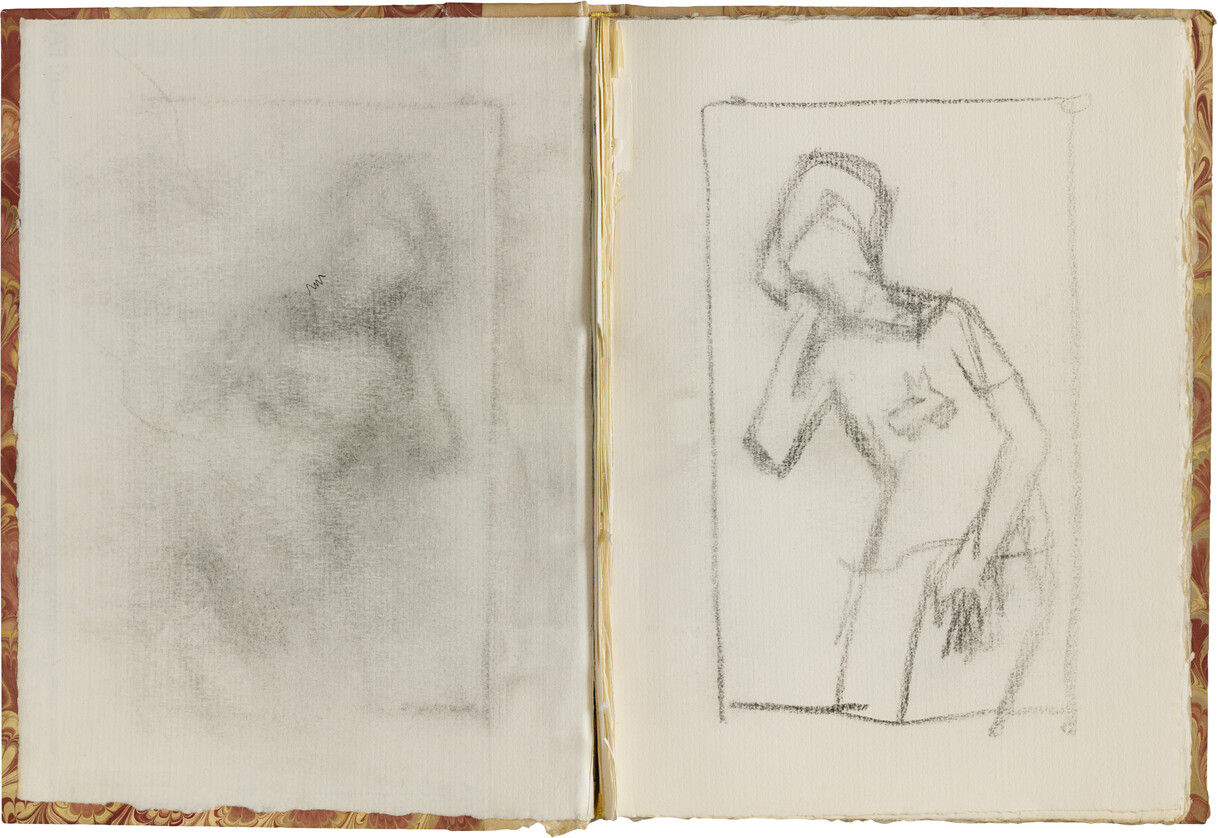

It was rare for Freud to repurpose books for his drawings.5 In most other cases, he purchased sketchbooks from artists’ suppliers, some of which usefully retain the suppliers’ labels. His most frequent and longstanding suppliers were Lechertier Barbe Ltd on Jermyn Street, London, where he bought papers and brushes from the 1950s until the business closed in 1970. After the closure, he continued to buy their papers from Ploton’s, a specialist artists’ suppliers in Highgate, north London, which had acquired the leftover stock.6 Some of Freud’s most elaborate, high-quality sketchbooks, which have distinctive red and sepia-toned block-printed covers, were bought from Legatoria Piazzesi, the longstanding paper shop in Venice.7 These sketchbooks have an ornate Romulus and Remus watermark in the corner of some of the pages.8 There are six examples of these books in the NPG archive.9 In one is a drawing of his daughter Annabel (b.1952), nicknamed ‘Ama’ FIG. 2. A rare example of one of Freud’s watercolour drawings, it was made while he was on holiday in Venice in the early 1960s with Annabel and her older sister, Annie (b.1948). Freud made several of these experimental watercolours, which include self-portraits as well as studies of his daughters, using Annie’s ‘Reeves’ painting box ‘with the greyhound on the lid’.10

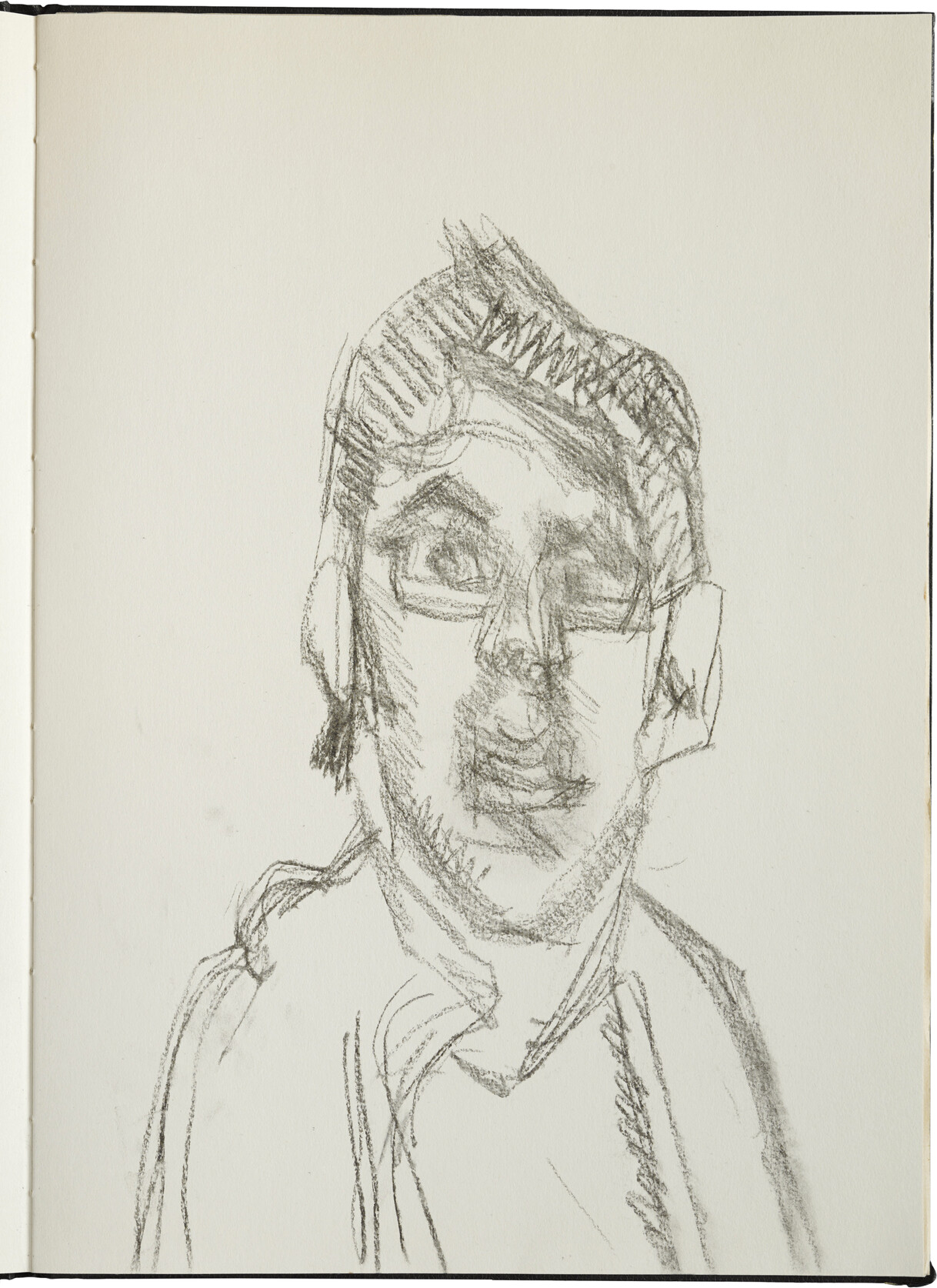

Freud used a variety of media in his sketchbooks, from graphite pencil, pen and ink to crayon, charcoal and watercolour. With support from Getty’s Paper Project grant, the paper conservation team at the NPG have been working to identify the media through visual analysis of the drawings and, where necessary, close examination under magnification. This has changed some assumptions. For example, many of the drawings that were initially catalogued as graphite pencil have now been recognised as being in crayon, which has a more smooth and consistent quality and is generally richer and denser in tone. Freud used crayon for many of his more detailed and finished drawings, such as one likely to be of the then sixteen-year-old Garech Browne (1939–2018) FIG. 3, who sat for Freud at Luggala, his family’s estate in County Wicklow, Ireland. Luggala was renowned for the hospitality of Garech’s mother, Oonagh Guinness (1910–95), whose illustrious guests included ‘Dublin intelligentsia, literati, painters, actors, scholars, hangers-on, toffs, punters, poets, social hang-gliders’.11 Freud would visit the Gothic Revival house and extensive grounds regularly with his second wife, the Anglo-Irish writer Lady Caroline Blackwood (1931–96), who was also Garech’s cousin. Despite Freud not making any attempt to outline the sitter’s face, Garech emerges from the paper through the artist’s meticulous observation of his plump lips and downcast, melancholic eyes. The fine detail and tight composition seem to have been translated into a finished painting, Head of a Boy (1956), one of Freud’s early masterpieces.12 Browne would become an important Irish arts patron, championing Celtic music and accommodating such musicians as the Beatles and Mick Jagger at Luggala, which he inherited. Of all the many creative people Browne met at Luggala, he reflected that ‘the person from whom [he] learnt most was Lucian Freud’.13

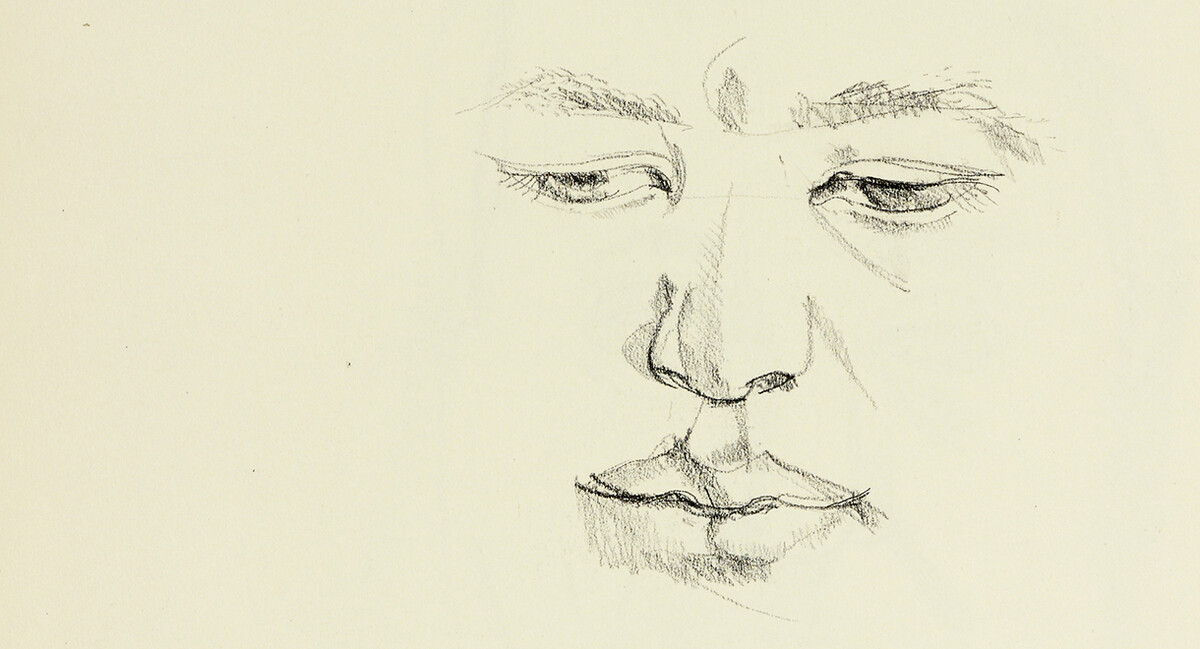

By analysing Freud’s choice of media, one also gets a sense of his experiments with mark making. It was often through drawing that Freud experimented and pushed the boundaries of his art. Decades after the Browne drawing, in around 1990, when Freud was an experienced and widely acclaimed artist, he made a drawing of his close friend and frequent model Susanna Chancellor. She appears aloof with her hair partially concealing her face FIG. 4. The drawing is heavily worked and is quite unlike any other in the sketchbooks, which is perhaps a result of the combination of media used. These included charcoal to outline the head and chalk and pastel to mould the face further, creating an almost three-dimensional effect. There is also evidence of stumping, a method of deliberately smudging the lines, perhaps with his finger or stump. Often in Freud’s portrait drawings, the heads float in space and there is an economy of line, a precision, but here he is heavy-handed, his marks vigorous and loose, covering almost every inch of the page. Susanna was a face Freud knew well. There are etchings, pastels and paintings of her from the same period: this drawing could be understood as a hybrid work, encompassing the embodied knowledge learnt from these portraits in a variety of media.

Freud famously said that ‘everything is autobiographical and everything is a portrait’.14 When one pores over the pages of his sketchbooks, one experiences the intimacy and immediacy of looking into the private world of the artist. The architectural historian Mark Dorrian has described the challenges of defining what a sketchbook is: ‘when we talk about the sketchbook what do we mean? Its complexity is reflected in the difficulty we experience [...] in straightforwardly attaching a name to it, for there are times it might seem to be equally a notebook, a journal, a diary, a travelogue, an aide-memoire, or even a scrapbook’.15 Indeed, in Freud’s sketchbooks, alongside the many hundreds of drawings, are reminders, draft letters and betting notes. In these ancillary materials we gain an unparalleled look into the daily routines and thoughts of the artist.

At times, Freud reveals his private and uncensored reflections on art, written down without concern for critical response. He remained staunchly committed to the human figure despite the emergence of abstraction, Minimalism and Conceptual art in the post-war period. In sketchbook no.6, dating to the late 1940s and 1950s, he reflected: ‘Abstract by its exclusion of Human or representatinal [sic] Object can never move the senses but can still at best have an ecsetic [sic] appeal only’.16 For Freud, it was the human figure above all that could create sensations. In the sketchbooks, there are examples of text and image working together. For example, in sketchbook no.8, beneath a drawing of himself with a lamp, he wrote: ‘Turn heads into naked people / bodies bodies whole complete / living naked women avoid / facial expression make bodies / expressive of feeling’.17 He wrote this when he had just begun making his ‘naked’, fleshy portraits in the early 1960s. Freud was uninterested in idealised and inanimate depictions of his subjects; he wanted to expose their true selves as ‘a physical and emotional presence’, as he described it, creating a portrait and not simply a likeness.18 Freud had a predilection for interweaving text and image even in childhood; this was first exemplified in illustrated letters to his family and in his early career in the form of commissioned book illustrations.19 The sketchbooks provided an ideal format to continue this method of communication and expression.

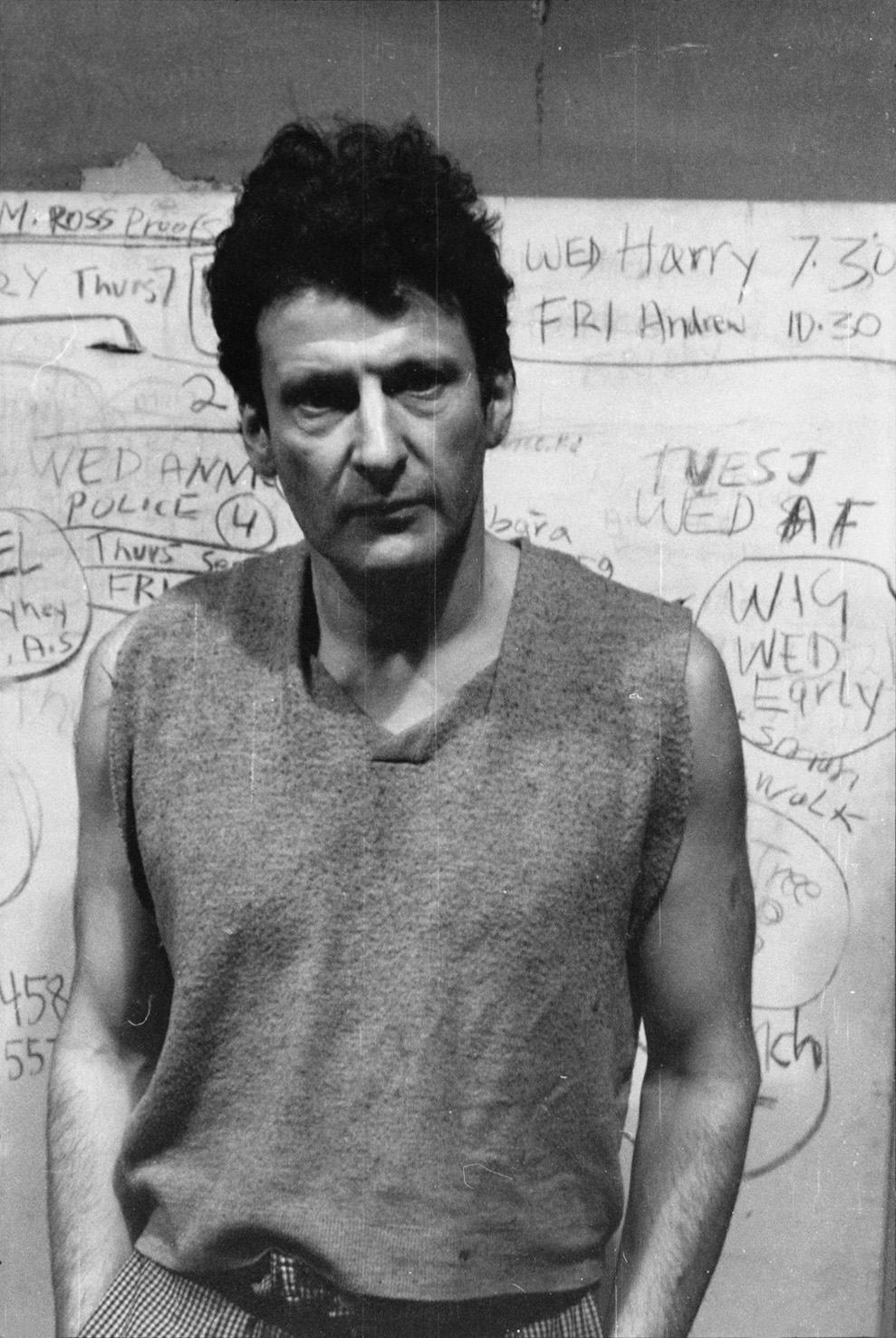

The sketchbooks also reveal his side passions. There are many pages of racehorse betting notes.20 Freud found gambling exhilarating and was subsequently banned from certain betting and racing circles after huge financial losses. Sometimes he simply used his charcoal and sketchbooks that were close at hand to jot down reminders of appointments. An example is in sketchbook no.27, where he wrote ‘BONO / TUES / 12.40’, presumably referring to a lunch date with the singer Bono, whom he was known to have met in Clarke’s in Kensington, one of his favourite restaurants in later life. Similarly, ‘RIA 6.30 / WEDNES’ was a reminder about an evening sitting with the art handler Ria Kirby, who sat for Freud in 2006–07 for a large oil painting, Ria, Naked Portrait, in which she is depicted lying on a bed with her blonde curls pressed against a pillow. These notes resemble Freud’s studio walls, which were similarly covered, as recorded in a series of photographs taken by Harry Diamond FIG. 5.

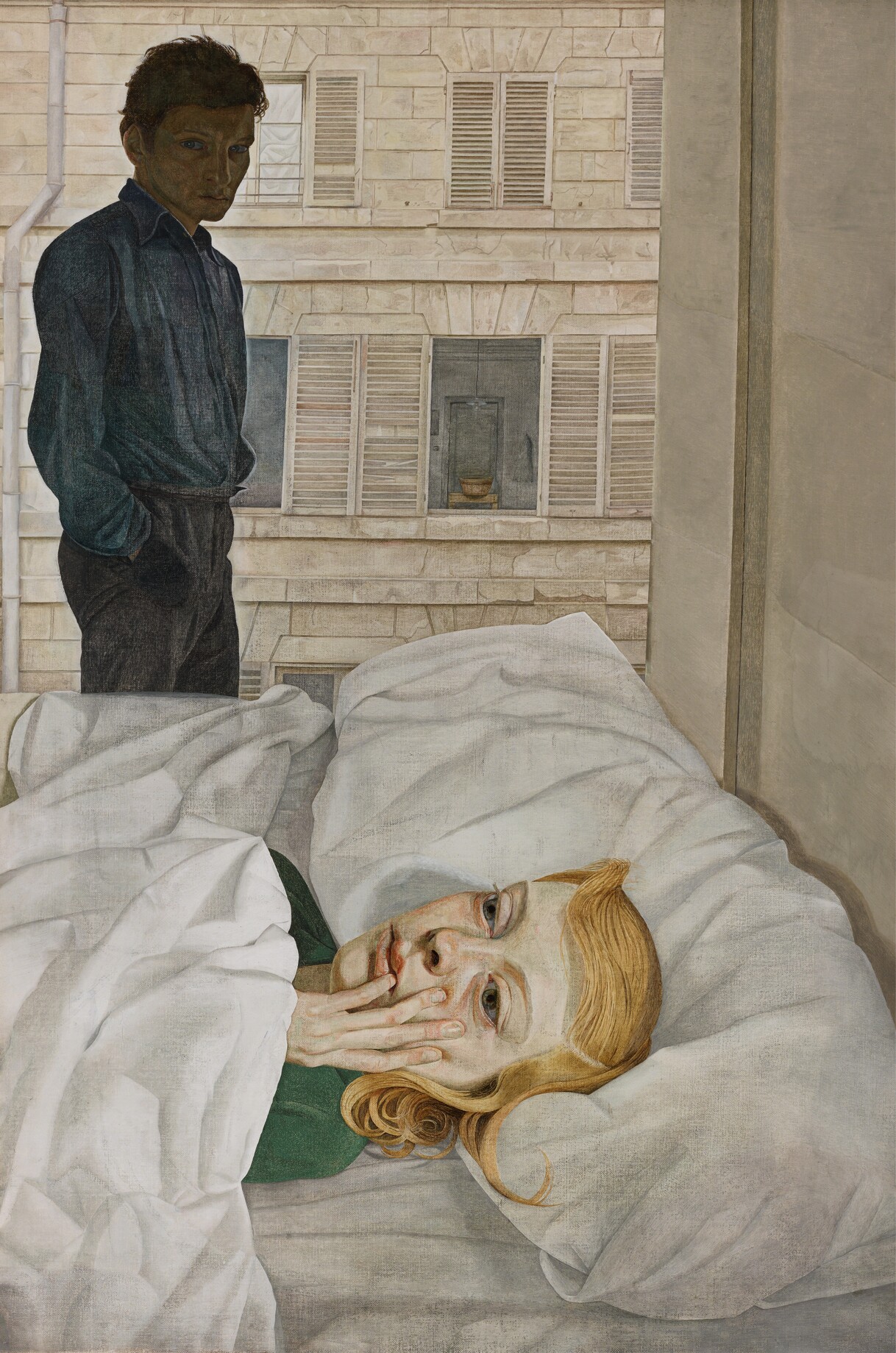

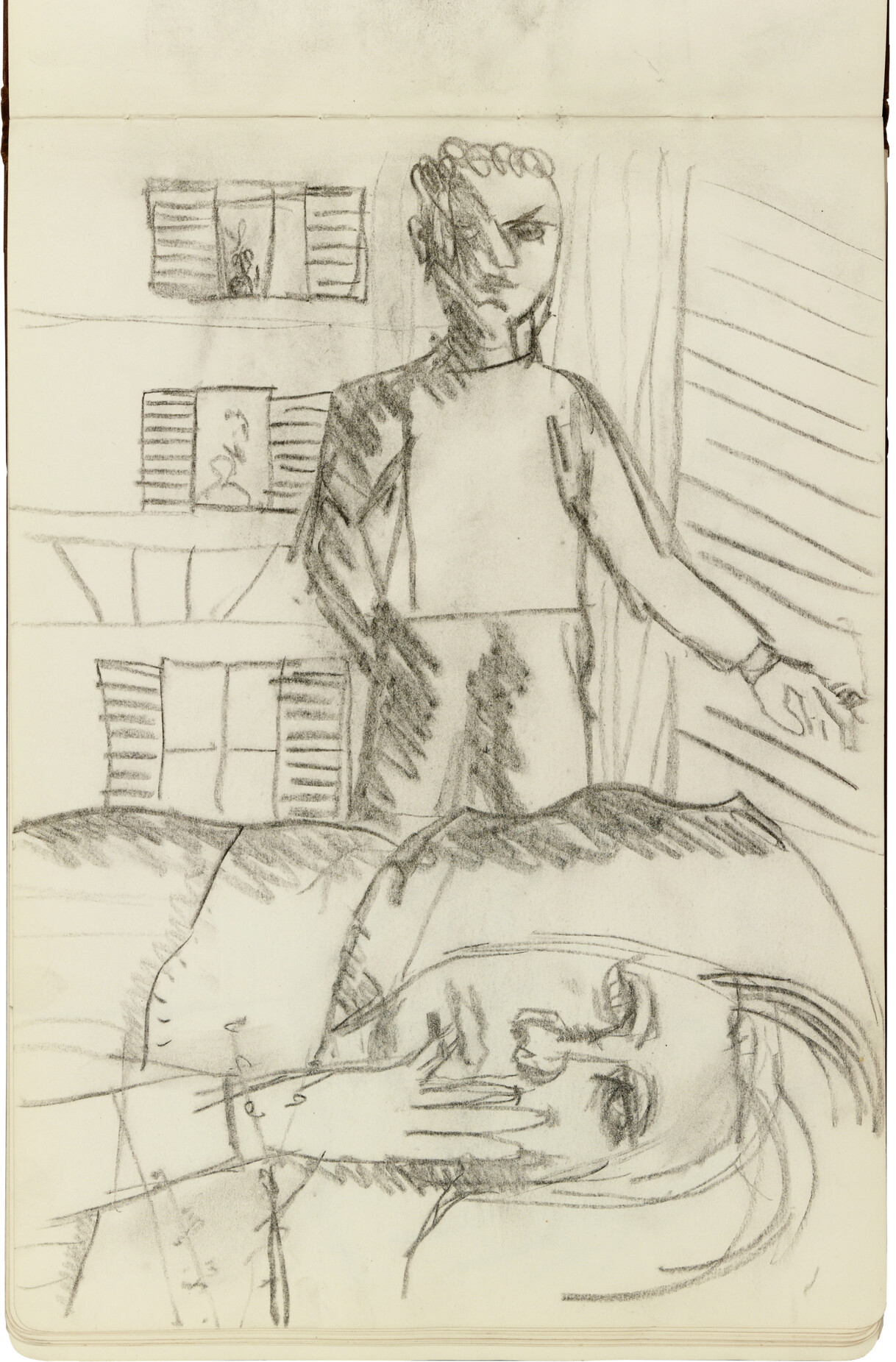

Perhaps most compelling are the drawings that relate to Freud’s now well-known paintings. There are preliminary drawings for his widely exhibited Hotel Bedroom FIG. 6: a portrait of Freud with Blackwood in the Hôtel La Louisiane, Paris. He worked on the painting in the run-up to the 27th Venice Biennale, where he represented Britain, alongside Francis Bacon (1909–92) and Ben Nicholson (1894–1982). The couple had married in Chelsea Town Hall in December 1953; a page in one of the sketchbooks records their aspirational guest list, which included Bacon, Man Ray (1890–1976), Cecil Beaton (1904–80), Graham Sutherland (1903–80) and the art patron Marie-Laure de Noailles.21 However, when this portrait was made, in the following year, their marriage was already breaking down. Freud evokes their growing estrangement in the painting: positioned separated from one another, Freud is a shadowy figure standing in profile while Caroline lies in bed looking anxious and forlorn, biting her nail. Freud recalled: ‘She was so disorientated in every way. I was terribly restless and Caroline was terribly nervous [...] The picture was at a difficult time. She wasn’t amorous, not very well’.22 In Caroline’s recollections, she put her look of distress down to the temperature of the room: ‘the room was so small that Lucian broke the window [...] That’s why I look so miserable and cold’.23 There are at least two studies in the sketchbooks that relate to the painting: one that is very close to the final composition and another FIG. 7 in which he is experimenting with the view in the background and his position in the portrait. Freud faces forward and both his and Caroline’s gaze meet that of the viewer, who, as a result, is invited into the image and made to feel complicit in their unhappiness.

There are also drawings that relate to one of Freud’s most complex and large works, Large Interior W11 (After Watteau) (1981–83), a painting that took two patient years to complete. It takes its inspiration from Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Pierrot Content (1712; Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid). Watteau’s jovial and idyllic garden party setting was reimagined in the cold, rough setting of Freud’s studio. The five figures that appear in Watteau’s fictional scene have been replaced with people from Freud’s inner circle: seated together are his lover Celia Paul (b.1959), his daughter the fashion designer Bella Freud (b.1961), Kai Boyt, who stands in for Pierrot, and his mother Suzy Boyt (b.1939), a former lover of Freud. The child lying on the floor was meant to be Freud’s granddaughter May, daughter of Annie. However, she was unavailable and was replaced with a reluctant child named Star, who according to Freud was ‘borrowed and bored’.24 Freud described the painting as a ‘family portrait’, revealing the way he conceived of his unconventional brood.25

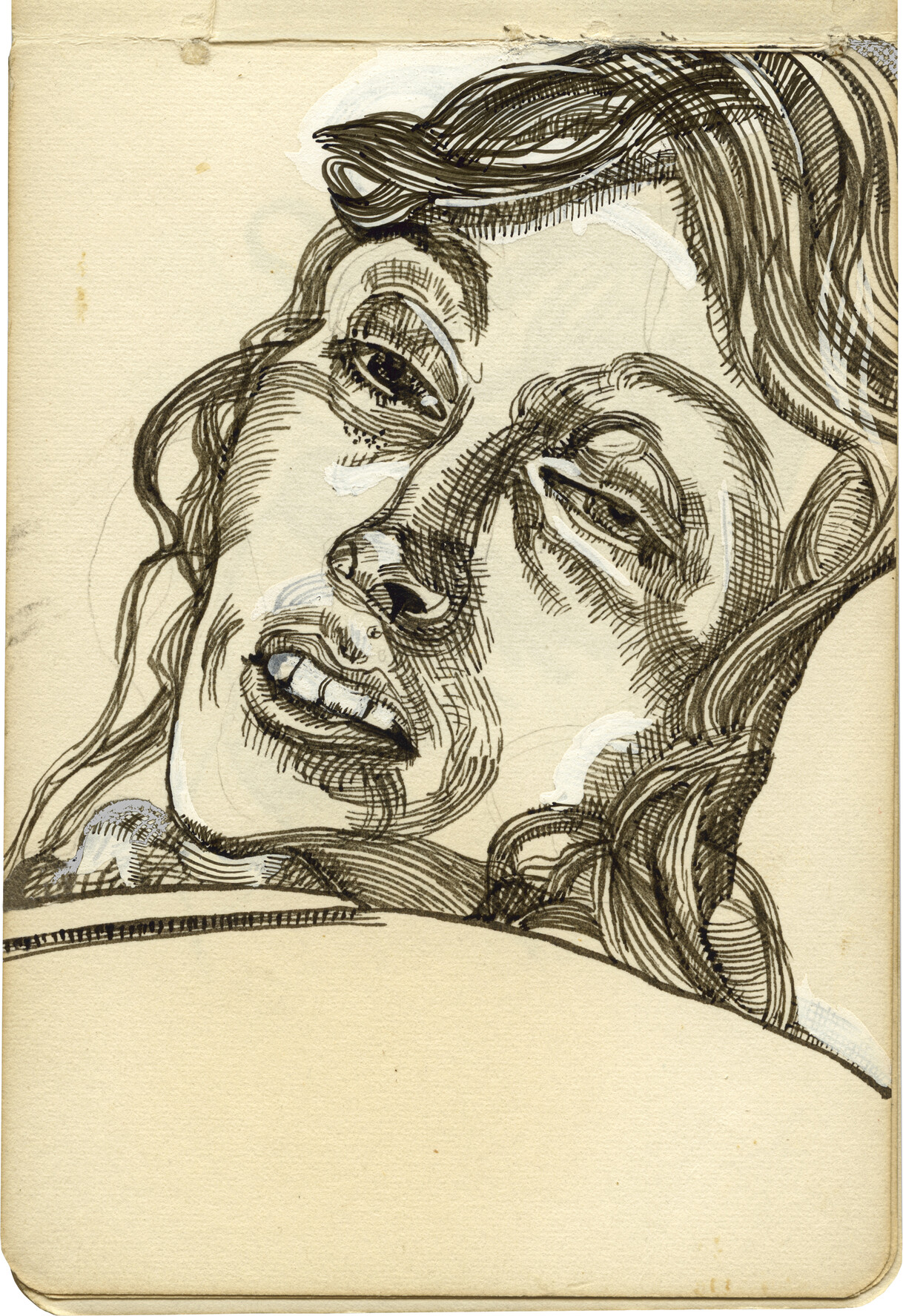

Freud told his biographer William Feaver that the painting took a while to set up and stage and that he had ‘been making drawings with the idea of doing a group painting, which [he had] never done’.26 There are several preparatory drawings in the sketchbooks that show Freud working out the composition, together with sketches completed after the painting.27 Freud is known to have made after-sketches, or ‘afterthoughts’, of some of his finished paintings; perhaps when the process had been so exacting and the result so compelling that he was not quite ready to part from it completely. A close study of Kai and Suzy matches the final composition of the painting almost exactly, even in the way the strands of hair fall across Suzy’s face FIG. 8.28 It is a detailed homage to the painting, the careful cross-hatching in ink accurately replicating the brushstrokes.

Having experimented with etching in the 1940s, Freud did not return to printmaking until 1982. The printmaker Marc Balakjian (1938–2017) of Studio Prints, London, with whom he worked closely from 1986, described how the technique Freud used – hard ground, line etching – ‘solely uses drawing’.29 Freud would place the etching plate on the easel and do a rough drawing in soft pastel onto the prepared copper plate to place the subject, in the same way he would begin a painting by drawing in charcoal on the canvas. Then, he began the drawing in earnest with his etching needle. As Freud noted to Feaver: ‘I want to familiarise myself with my materials to such an extent that, having them to hand, I can use them [...] I think that these things are terribly private; I know that going from one medium to another, from drawing to painting, say, does refresh’.30

It has been acknowledged that there was a close relationship between Freud’s etchings and his paintings.31 Often, he made an etching of a sitter who he was already familiar with from painting them. However, little if any attention has been given to the connections between Freud’s drawings in his sketchbooks and his etchings. There are several drawings that relate directly to finished etchings, including The Conversation (1998) and Bella in her Pluto T-Shirt (1995; Tate). There are also drawings of such sitters as Bruce Bernard (1985), Lord Goodman (1987) and Susanna Chancellor (1996), which closely resemble the etchings he was making at the time.

Notably, Balakjian remarked that on two occasions Freud made substantial changes to his etching plates. In Bella in her Pluto T-Shirt, his daughter is shown sitting in a chair, her head resting on a clenched fist and her other hand on her thigh. She wears a t-shirt emblazoned with the logo of her fashion brand: a simple drawing by Freud of his pet whippet, Pluto. Freud asked Balakjian to erase the head on the etching plate twice so that he could redraw it completely. There are several drawings in the sketchbooks that demonstrate Freud testing out different possibilities, perhaps before committing himself again to the etching plate. In one quick sketch, Bella is gazing down as was the case in the first unsatisfactory state of the etching, the panting dog motif still front and centre on the t-shirt. In another, he maps out the pose, but leaves the head faceless FIG. 9, resembling the erased head of the plate, still undecided as to his next move, until finally in the finished state he allows Bella’s gaze to meet the viewer.

For the most part, the sketchbooks reinforce what we already know about Freud: he was an intense observer of people. They are full of tender moments, including mothers feeding their newborn babies and Pluto curled up asleep among his studio rags. They are evidence of the many hours of scrutiny of his subjects – revealed not through the layering of paint onto canvas, but from the numerous pages dedicated to a single sitter. We know from first-hand accounts that sitting for him was a demanding and lengthy process. A series of drawings of Jacquetta Eliot, with whom Freud had an intense affair in the 1970s, is particularly striking. They are drawn in pen and ink in a very small sketchbook, of which the cover has come off, so it was presumably well-used. In one, he has used an opaque white medium FIG. 10 – possibly gouache or correction fluid – to highlight and correct areas of the drawing.32 As with most of the portraits in Freud’s sketchbooks, he draws only the sitter’s head. Here, Jacquetta looks tired, her eyes half open. At one point she sat for Freud four nights a week in his studio. She later recalled: ‘dead tired from looking after the children all day, not having a proper nanny. Why was I doing it? [...] It was difficult fitting the sittings in, terrible stress and strain. It did make me somebody basically I’m not’.33

Research for the Getty Paper Project has uncovered previously unidentified sitters in the sketchbooks, including three drawings of Frank Paul (b.1984), Freud’s youngest son with Celia Paul.34 They date from the time of the sittings between 2006 and 2008 for Freud’s only painted portrait of Frank. For Freud’s children, in his later life, sitting for him in his studio was often the only way to spend time with him. Although Frank was used to sitting for his mother, he had to quickly adapt to the unspoken language of sitting for his father:

He would step away from the easel to tell me to tilt my head a little bit in one direction. Sometimes [...] I would realise what he was up to and tilt my head in what I hoped was the right direction before he asked me, and if I had managed to tilt my head in the right direction, he would say with a mischievous smile and narrowed eyes that he was very impressed, but if I guessed incorrectly and tilted my head even further in the wrong direction then he’d give a slightly pained wince.35

Frank only discovered that the painting of him had been completed when it was exhibited at the Freud Museum, London, during the centenary celebrations of Freud’s birth in 2022.36 He thought that the portrait had been abandoned when sittings abruptly stopped after he turned up late to a session as a result of transport delays from Cambridge, where he was studying. Frank now views this episode with slight remorse: ‘I was sitting for him when I was a student at university. I think if it would have happened more recently, I would have been more organised’.37

The charcoal drawings of Frank in the sketchbook are rough and quick and yet expertly capture his hesitant, wide-eyed look, growing sideburns and hunched posture. He is depicted talking, unaware of his father’s gaze, unlike in the painting, in which his eyes are downcast, reading, as he recalled, The Day of the Locust (1939) by Nathanael West – ‘[Freud] was impressed’ – and then a large biography of Gladstone.38 Reflecting on the drawings further, the first time that he had ever encountered them, Frank remarked:

It feels very loose and my eyes are really turned towards him in a way they definitely weren’t when I was sitting for him for the painting [...] I don’t feel like if I had been actually conscious of being still then I could have been able to maintain eye contact for long enough for it to make a satisfactory drawing.39

In one drawing, there are areas that come into increasing focus and Frank’s glasses, nose and mouth are drawn from two different positions, laid on top of each other, replicating his movements FIG. 11. In Frank’s recollections of his sittings, there is a sense of a son eager to please, conscious of his actions and of being looked at by a world-renowned portrait painter. However, in these quick observational drawings Freud captured a moment of unselfconsciousness that most truly reflected his sitter, which was his ambition for all of his portraits.

Freud once approached the political cartoonist Nicholas Garland, whom he admired, when he was drawing in the private member’s club Annabel’s and asked him how he could ‘possibly draw in public like that? He [Freud] couldn’t do it to save his life’.40 For vast parts of his career, as the sketchbooks reveal, drawing was for him an intensely private activity. It served many purposes: it allowed him to experiment, to familiarise himself with his sitters and to express his inner thoughts. He was a remarkably gifted draughtsman throughout his career, and not only in the early part of it. Freud’s sketchbooks may have been kept in his studio until he died, but now, preserved in the NPG’s archive, they provide an intimate and illuminating record of his life and drawing practice.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Getty, whose generous support as part of the Paper Project has made further research into Lucian Freud’s sketchbooks possible. This research together with the display of materials from the Lucian Freud Archive at the NPG has been a collaborative project, with the archivists Carys Lewis and Claire Jackson, the paper conservators Rosie Macdonald and Tanya Millard and the Senior Curators, Rosie Broadley and Sarah Howgate.

-2.jpg?ixlib=rb-0.3.5&ixid=eyJhcHBfaWQiOjEyMDd9&s=3566466d76117e29ffb4160a639748fb&auto=format&fit=crop&w=1502&q=80)

.jpg?ixlib=rb-0.3.5&ixid=eyJhcHBfaWQiOjEyMDd9&s=3566466d76117e29ffb4160a639748fb&auto=format&fit=crop&w=1502&q=80)

.jpg?ixlib=rb-0.3.5&ixid=eyJhcHBfaWQiOjEyMDd9&s=3566466d76117e29ffb4160a639748fb&auto=format&fit=crop&w=1502&q=80)

-2.jpg?ixlib=rb-0.3.5&ixid=eyJhcHBfaWQiOjEyMDd9&s=3566466d76117e29ffb4160a639748fb&auto=format&fit=crop&w=1502&q=80)