Feeling with fingers that see: Simryn Gill’s ‘Naga Doodles’

by Emilia Terracciano • June 2023. In collaboration with Drawing Room, London • Journal article

Paper serpents

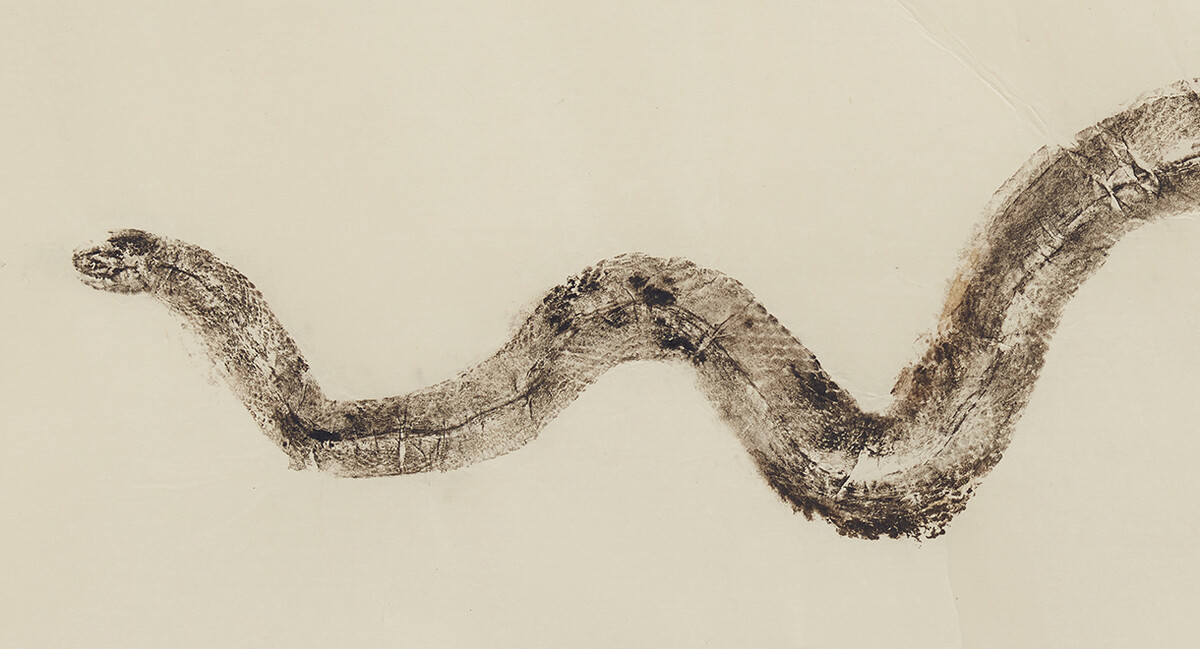

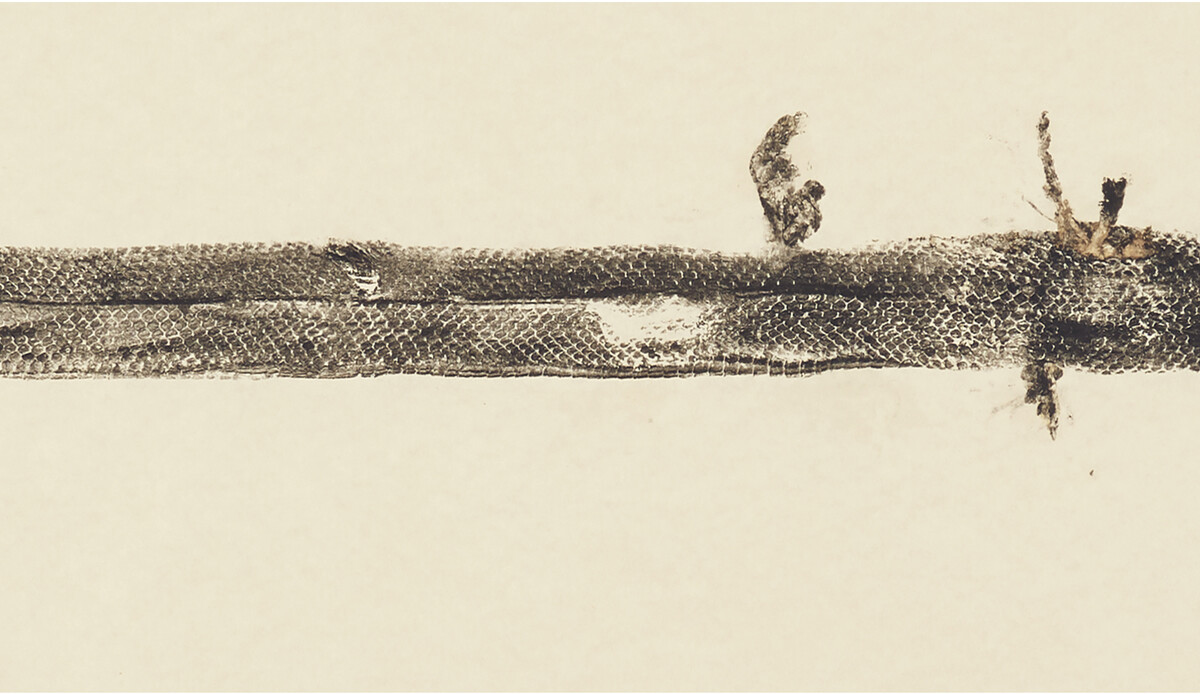

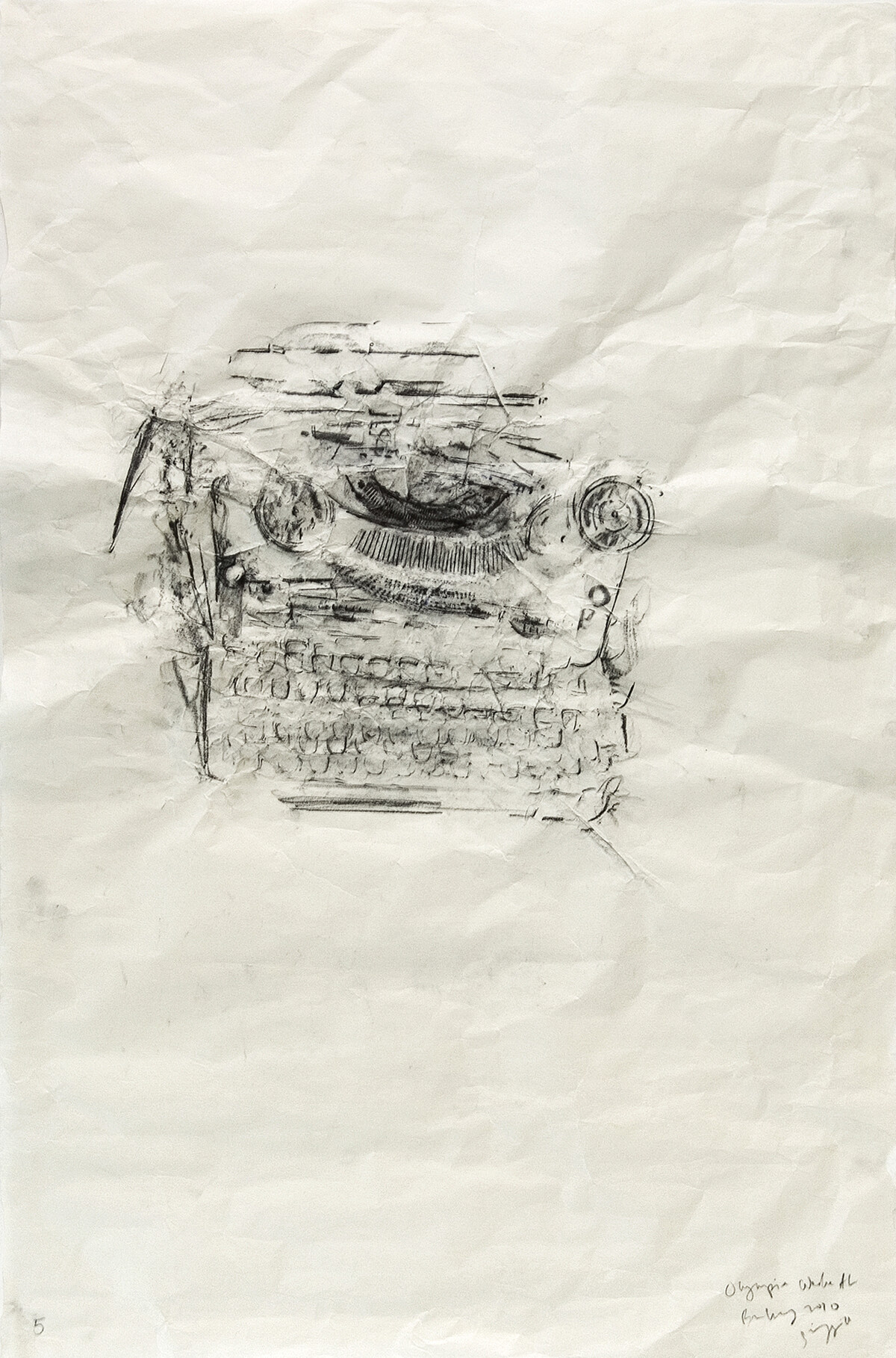

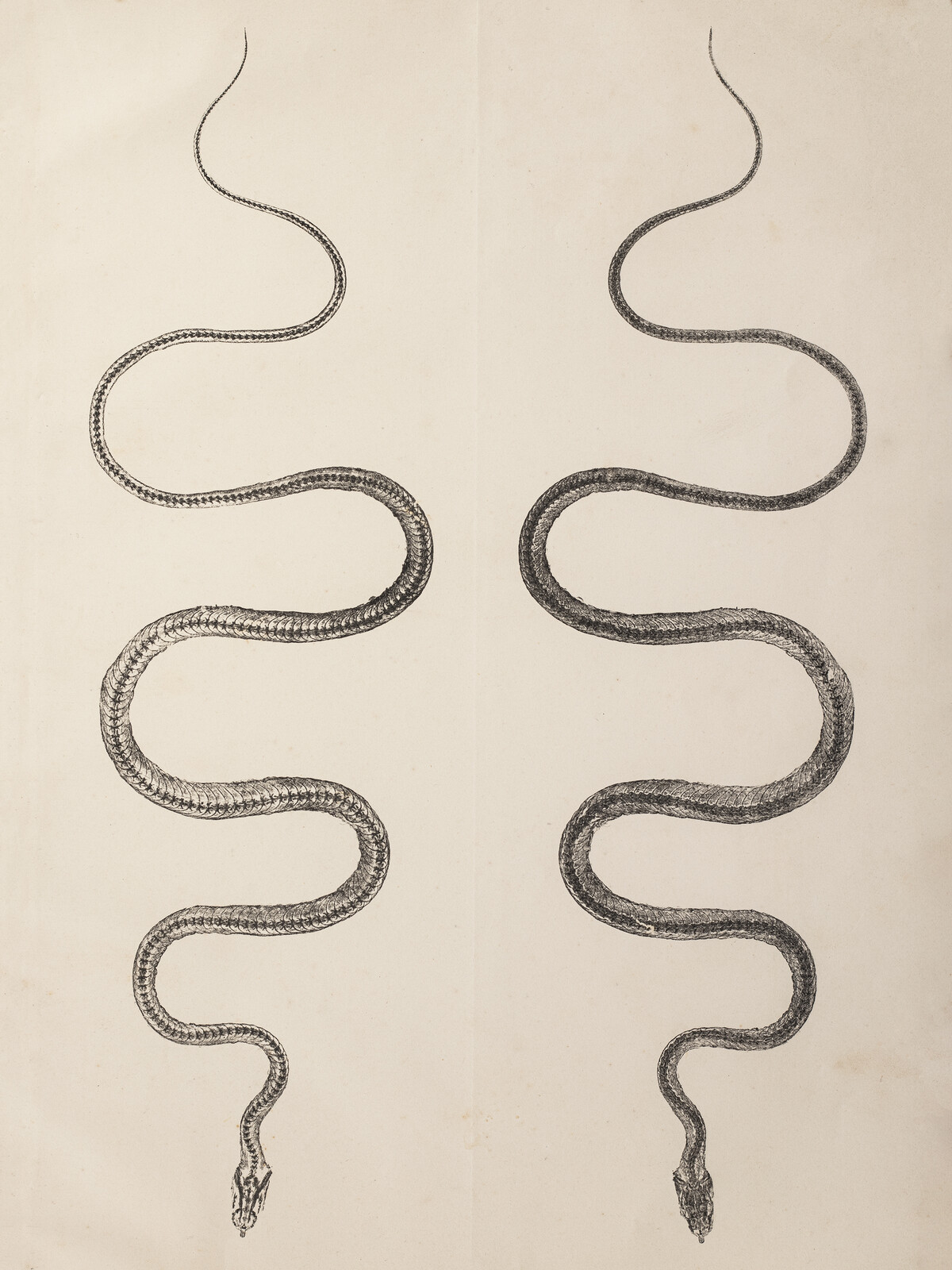

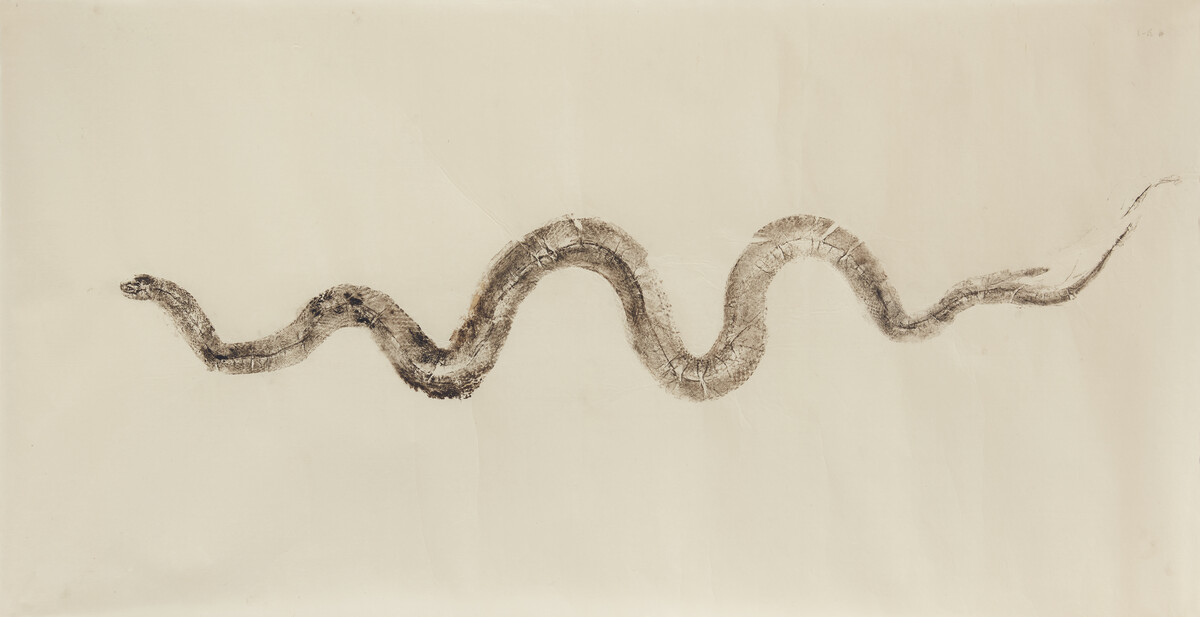

The inked lines curl and sweep across the large sheets of paper; others glide, wriggle and flow upwards FIG. 1. They are gestural and appear to be produced with little exertion: there is no jerk or reflex motion, but instead a continuous progression of graceful curves. Their charge is all the more potent because they seem to have been made spontaneously. Some are thick and some are thin, apparently depending on the amount of ink and water used, type of brush stroke and degree of pressure applied. Indeed, one could be fooled into believing that these are the dexterous doodles of a calligrapher. However, by pausing and looking closely at these marks one learns otherwise. Lurking, or hiding in plain sight, are snakes – or to be more precise, the direct impressions of snake skin transferred by rubbing onto Japanese rice paper FIG. 2 FIG. 3.

Simryn Gill (b.1959) created this series of prints or rubbings in 2017. She called it Naga Doodles: in Malay naga means dragon; Nāga is also the Sanskrit and Pali word for serpent, as well as a semi-divine, part-human part-snake being, specifically, the king cobra that appears in the iconographies of the religions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.1 In the Hindu tradition, they dwell in the underworld, guarding the treasures of the earth; they are also associated with bodies of water and the powers they hold. Although minor deities, Nāgas are powerful beings, thought to possess knowledge of all the sciences. They control the rain and offer protection against fires caused by lightning. In the Buddhist pantheon, they act as protectors. According to one legend, they led the great Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna to their underground lair, where he rediscovered the lost Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya Mahayana texts.2 Perhaps the best-known legend is that of Mucilinda and the Buddha. During a storm Mucilinda takes the form of a many-headed cobra and out of pity surrounds the meditating Buddha with the coils of his body, forming a protective awning with his hood.3

Gill, who describes herself as a maker and keeper of records, has long engaged with indexical, manual and record-making processes that yield complete renditions of objects or vegetal and animal matter collected or found within her immediate surroundings. Naga Doodles comprises more than ninety rubbings of roadkill snakes scraped by hand from the tarmac within a fifty-mile radius of the artist’s home on the west-coast peninsula of Malaysia. Later, in her studio, Gill inked each carcass and placed a sheet of paper over it, which she then rubbed with an up-and-down or circular repeated movement. She did this without looking and, finally, slowly peeled away the paper. After the process, she buried each body. The result of this calculated, laborious, slimy and somewhat gruesome process is precisely rendered rubbings of flattened, torn membranes, unfurling ribbons of tissue, with occasional blotches of guts, excreta and blood.

Reviled and adored, perceived to be lethal and awe-inspiring, snakes can symbolise both death and the renewal of life, due to their ability to shed their skin. They can be found in the religious beliefs, ceremonies and legends of many living cultures. In the Western tradition, snakes are widely perceived as powerful and malevolent creatures: in the Bible a snake tricked Adam and Eve, causing God to expel the couple from the Garden of Eden. In Asia, mythical snakes abound and often assume the shape of a human as a form of disguise.4 In Southern India, up until the early twentieth century, the act of harming a snake caused much fear and whoever happened to kill one had to lie in a running stream of water in daylight for several weeks. The body of the snake was then buried in a trench, similar to that of an elder.5 Moreover, in some communities killing a cobra was considered a sin; the deceased snake was burnt in the same way as the bodies of humans, and the murderer was considered polluted for three days.6

Nineteenth-century Europeans concerned with studying the mythologies surrounding this reptile were primarily fascinated by the snake’s furtive movements. Its seemingly mysterious motion prompted a multitude of scholarly investigations and theories.7 Snakes puzzled explorers, naturalists, scholars and art historians, who found their locomotion counterintuitive – it dislocated human thinking.8 ‘We understand being bird, being ant, being lizard: but to be serpent, to have no legs or arms, to move by wriggling, coiling up in spirals, slithering on your belly, that’s something extraordinary! How can one be a serpent! Just thinking about it puts the imagination to torture’, wrote the French philosopher Paul Souriau in L’Esthétique du Mouvement.9 The serpent’s smooth and graceful crawling also arrested Aby Warburg’s imagination: he described the body of the snake as a ‘moving line’,10 one that hovers on the threshold between submission to anonymous, even magical forces, and the release of ‘individualised freedom’.11

Gill is far more prosaic about snakes. She has explained that ‘More or less flattened, they presented themselves to me as “printable”. When I see them on the roads now, they seem to me like found drawings, absent-minded doodles’.12 In her pragmatic, even casual manner, Gill shares her impression of these animals as found, man-made marks. Cleared of the labour of killing the creatures, she limits herself to notice and scrape up the mess.

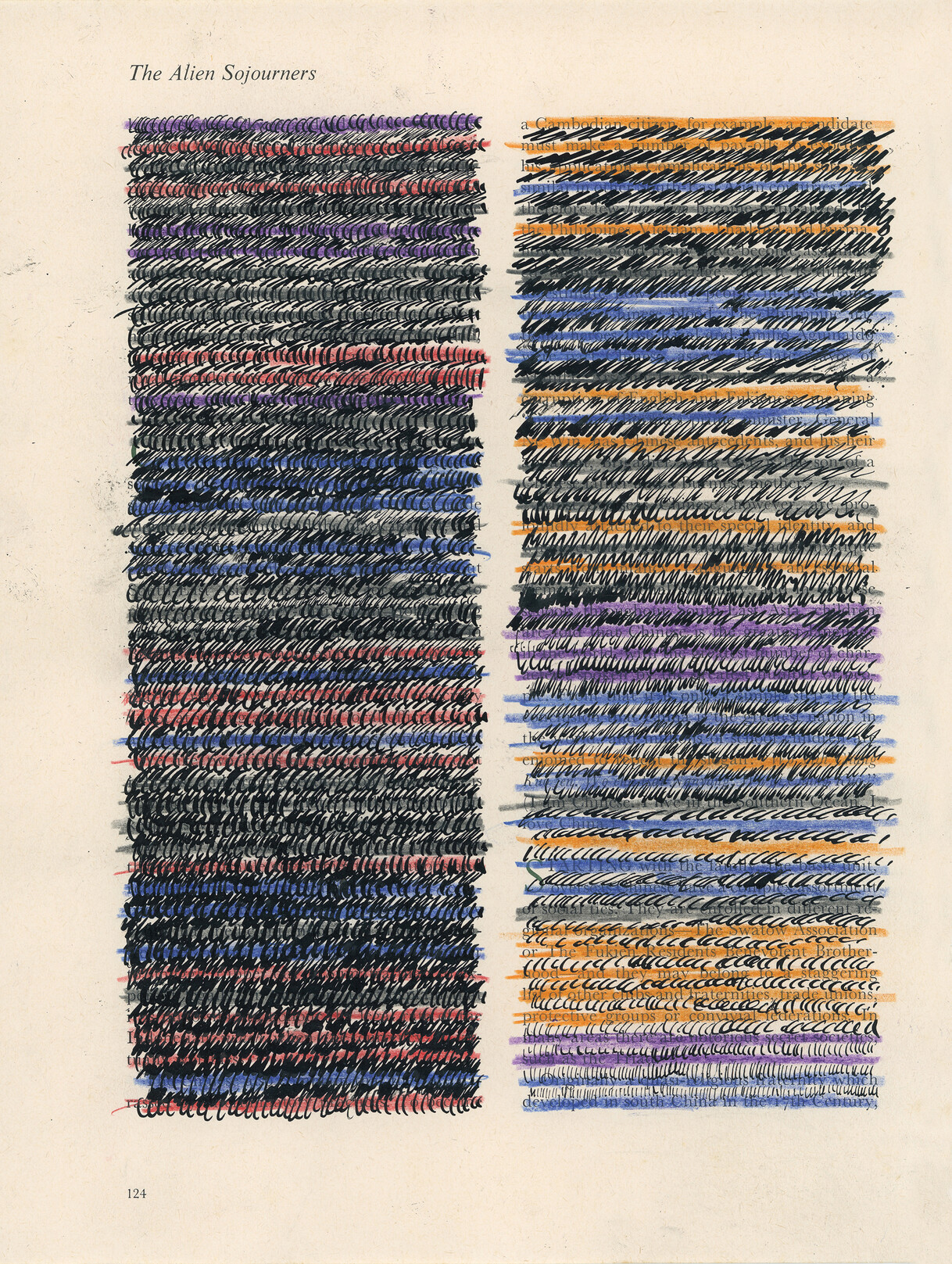

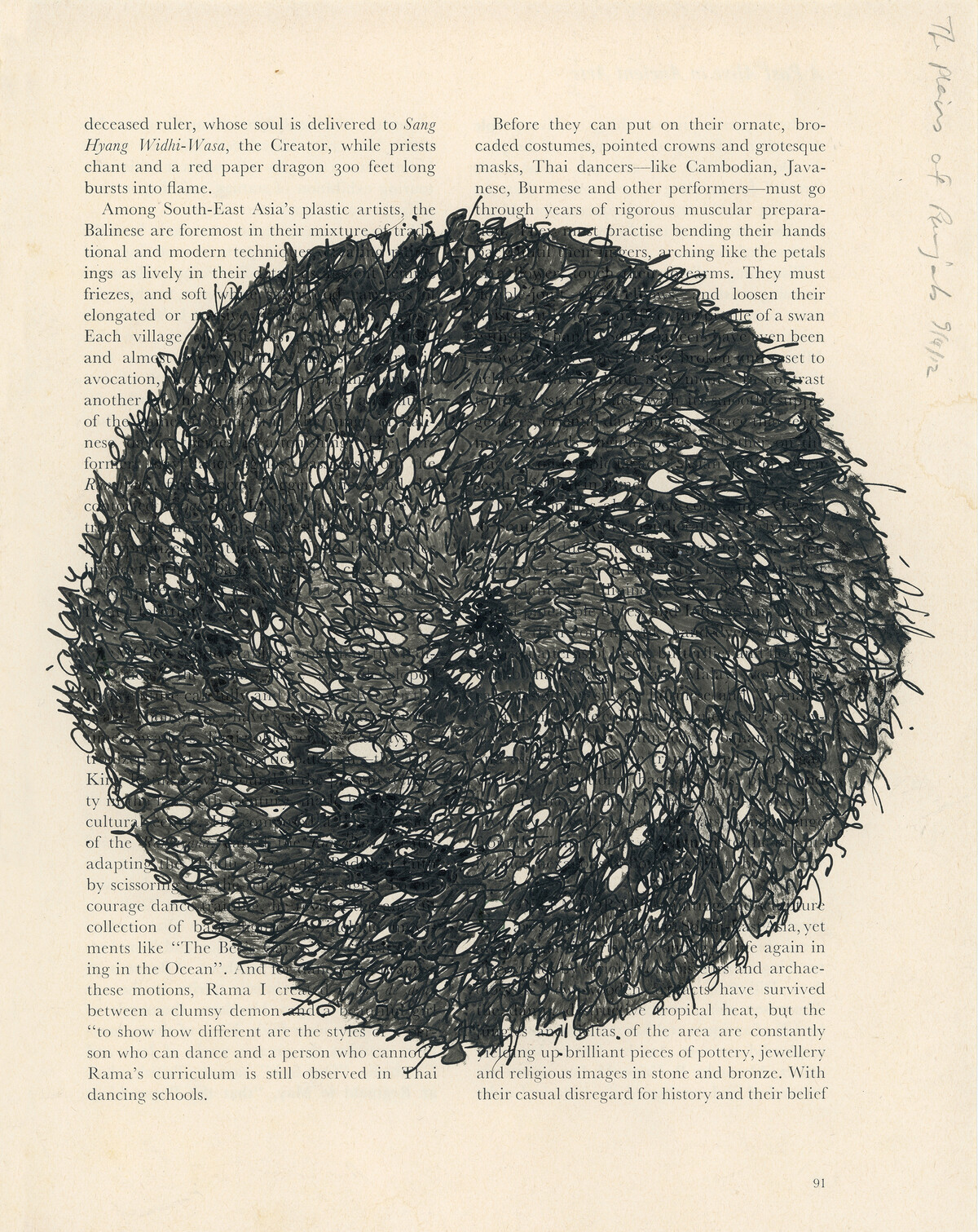

As a maker of books, and a bookish artist, Gill is more than familiar with paper; she is also a prolific collagist and a consummate doodler. Worming her way through pages, she creates graphic permutations that often take on a life of their own FIG. 4. Her forms of pictorial truancy serve a variety of purposes that one can only guess at: for example, relief from laborious tasks, creative idling, play and escapism or some kind of comment or attack on the printed text, and by extension, its authority FIG. 5.13 This article will assess Gill’s rubbings as a form of doodling, one that is repetitive to the point of being mechanical. Both ‘rubbing’ and ‘doodling’ engage the practice of drawing at its most basic and simplest level, producing images at the threshold of the medium. This regression, or degree zero, of drawing leads us back to the most elementary kinds of marks. Indeed, both doodling and rubbing defy the mastery and skills of mind over matter that has historically characterised the traditional practice of drawing. They rely on a deliberate suspension, absenting or removal of agency in favour of a kinaesthetic, gestural and haptic way of learning. This ostensibly childish way of making may resurrect a lost mode of spontaneity, leading one back to a vanishing past. These ‘images of a lost innocence’ are made even more poignant because of a forced and fantastic childhood.14

A crucial difference between rubbing and doodling is that in the case of the former, the elimination of vision, by placing paper over the object, yields images that, although spontaneous, are decisively not invented. Hence, the technique or craft of rubbing taps into a broader range of art-historical issues dealing with the conventions of representing ‘nature’ and the epistemic challenges posed by taxonomy. The ambiguous, even opaque status of Gill’s images offers an opportunity to revisit debates surrounding the making of ‘objective’ images, alerting one to the ongoing tension between manual and mechanical ways of sensing and knowing. Ultimately, Gill forces one to see with one’s fingers, divining and making visceral sense of the world through touch, without the aid of sight.

Rubbing it in

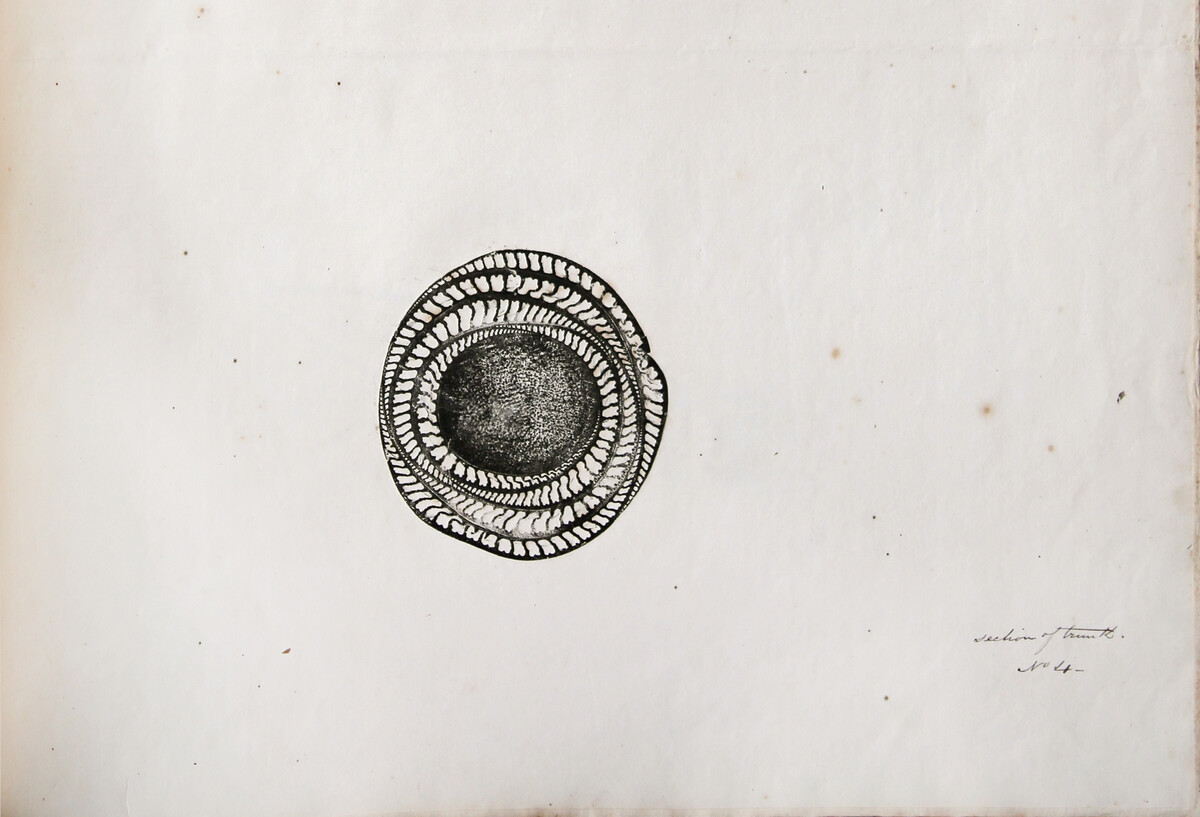

Rubbings are one of the most basic forms of drawing. They also happen to be one of the most ancient and widespread techniques used in printmaking. Since their inception, rubbings have been prized for their immediacy and efficiency, simplicity and accessibility of skill: minimal labour, artistic literacy and accuracy. Traditionally, they are produced by gently pressing paper onto a carved or relief surface so that it covers or conforms to the underlining features. The paper is then blackened so that areas in relief become dark, while the indented ones remain white, resulting in an accurate and full-scale facsimile of the surface. In the past, rubbings were regarded as truthful records of the labour of others. Some of the earliest examples of rubbings, dating to the second century AD, are to be found in eastern Asia, specifically in China, where the practice was used to disseminate Confucian texts.15 Such texts were carved on monumental stones, and by imprinting them on the cheaper, more portable medium of paper, they could be shared widely. Much later, during the Edo period in Japan, fishermen engaged in the recreational practice known as gyotaku, meaning ‘fish rubbing’ or ‘fish impression’, inking the catch of the day and pressing it onto paper to record the size of fish.16 The result of this process is an accurate copy that displays the specific textures of each animal specimen.

Over the past two decades, Gill has produced different kinds of rubbings involving diverse materials and techniques. These material records are always linked through action to a specific place and time, be it private or public. Moreover, they eschew vision altogether, placing emphasis instead on touch or the hand; as Gill puts it: ‘using the hands as the eyes in touching and caressing the objects, and this without flattening them on the paper in a two-dimensional manner’.17 In the process of creating rubbings, textures and patterns appear through the interplay of pressure and resistance, soft graphite and hard ground: the tactile becomes a visual manifestation. The initial challenge for Gill was to retain the three-dimensional properties of the objects on a two-dimensional surface. She placed a sheet of paper directly on top of the object and then rubbed it with graphite. Her first recorded rubbing, created in 1987, involved a complex, hard, three-dimensional kitchen utensil: an egg-beater. The result of this process is a creased impression that has a gestural, abstract, even improvisational quality. The familiar tool becomes unfamiliar: a tentacular creature that is funny, yet also alien and potentially menacing.

Whereas Untitled (eggbeater) (1987) gestures towards the home, and the drudgery or tedium of domestic labour, Gill’s later graphite rubbings series relate to movement in familiar spaces and spotting hidden or unseen things. In 1997 she made Sydney Maps, rubbings of cracks in pavement stones in the streets of the city she had moved to. Perhaps her most well-known series is Caress FIG. 6 – rubbings of vintage typewriters once located in the famed ‘typewriters’ lane’, a stone’s throw away from the Small Causes Court in Mumbai.18 For Gill ‘these outdated writing tools in the land of IT and high-tech development behold certain marvel’.19 Produced without the aid of sight, the rubbings are records of the tools used by typists to write ‘affidavits, pleading to the courts for sentence reduction, mournful applications over property disputes or more prosaic filling in of administrative and bureaucratic forms, or letters for mothers and lovers’.20 They are sensual and visual renditions of the ‘fingering of the typewriter in transferring the relief to paper’.21

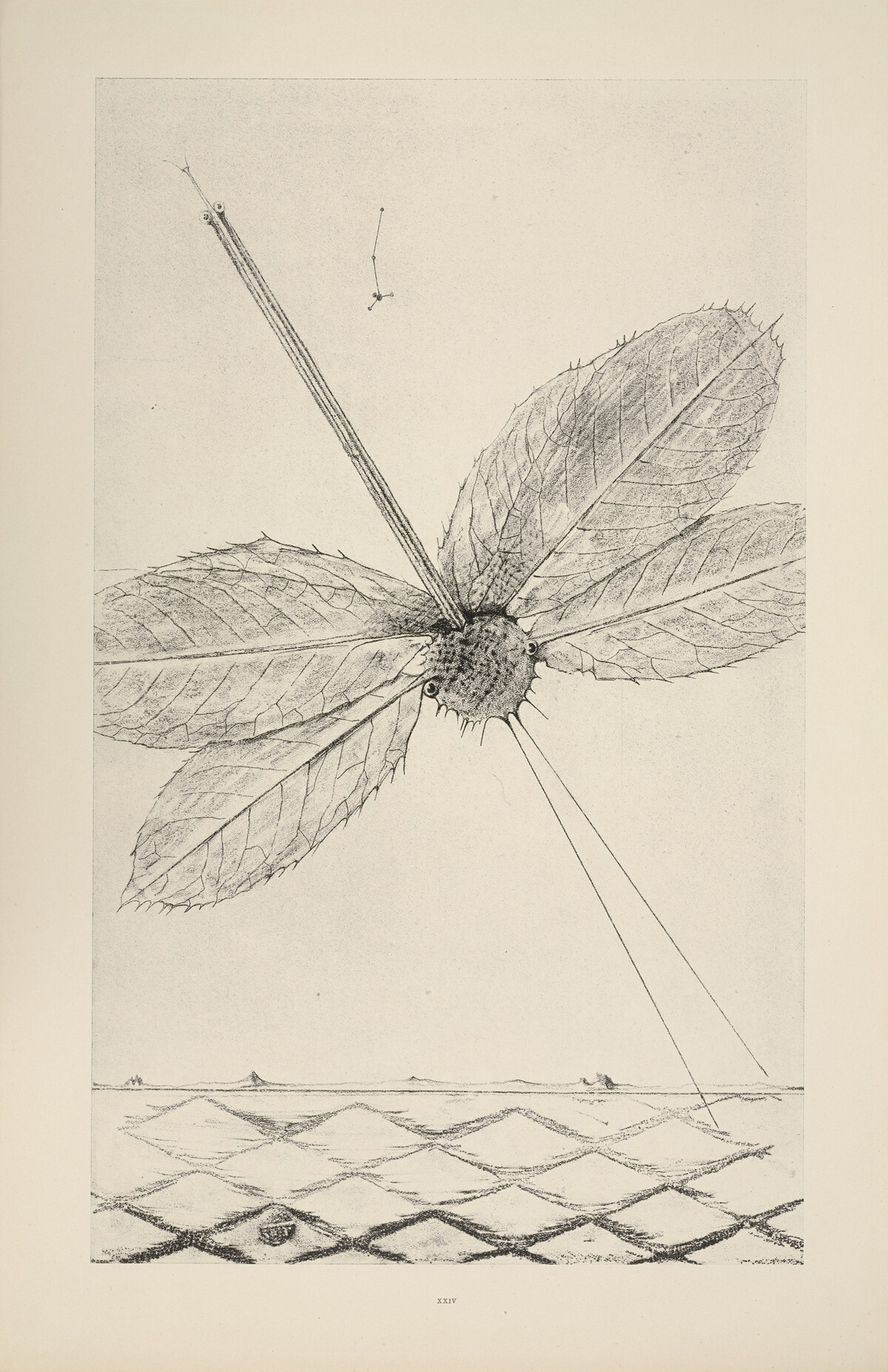

It is in relation to this latter body of works that writers have invoked the legacies of Surrealism to describe Gill’s rubbings.22 The typewriter is also an instrument associated with the Surrealist movement, specifically with automatic writing, which ostensibly provided a direct route to the unconscious.23 ‘Automatic’ is a word that also emerges in relation to the technique of rubbing, or frottage (from the French word frotter, meaning to rub), a process developed by Max Ernst (1891–1976) in which he constructed composite images from layers of rubbings. Ernst’s frottages published in Histoire Naturelle FIG. 7 were a deliberate form of technical atavism, one that could advance a hallucinatory interpretation of the ‘real’ that had little concern for the ‘objective’.24 Frottage embodied the new Surrealist call for automatism in visual art, ‘a step away from the vestigial “technique” required by oil painting or the precise assemblage required by collage’.25 In this reading, frottage incarnated the Surrealists’ outright rejection of ‘outmoded attitudes in art and pedagogy’.26 Above all, it was an anti-authoritarian gesture: through a process of graphic alchemy it turned base matter, such as floorboards, leaves or twine, into patterned composites. Such ‘automatic’ images were revelatory.27 In this respect, as noted by Elizabeth Legge, there is nothing ‘natural’ about Ernst’s Histoire Naturelle.28

Gill’s rejection of the primacy of the eye in favour of touch resonates with the Surrealist call for more ‘primitive’, infantile and spontaneous experiences. Yet her rubbings are altogether different: they are what they are. As such, it is useful to note that Gill has recently taken up the descriptor ‘nature print’ to describe her actions, making a conscious effort to withdraw her work from authoritative readings of the past.29 Grabbing, touching or feeling one’s way through might be the way, as Giuseppe Penone (b.1947) has written in relation to his own rubbings (albeit in an altogether different context), ‘to approach things without any cultural convention [...] an attempt to search for some basic values and notions not part of society’s patrimony. The imprint is an automatic, animal, primordial image that does not pose the problem of cultural knowledge’.30

Drawn from nature

Gill’s investment in rubbing vegetal and animal matter – and her use of the terminology of ‘nature printing’ – references a specific lineage of this technique, one that is bound up with debates about the conventions for representing nature ‘objectively’. Such debates occurred in the context of global colonial frictions and the creation of a visual glossary of empire from the mid-seventeenth century. The sense of vision was considered the best method for investigating nature, with images furnishing the most efficient way of transferring knowledge about an ‘exotic’ place. In Europe, rubbings, or nature prints (sometimes the two terms were used interchangeably) were recognised as the earliest precursor to the technology of photography. The process developed as early as the seventeenth century and became increasingly integral to the study of previously unknown flora and fauna FIG. 8, albeit predominantly of the former FIG. 9.31 It involved covering a specimen with a thin, even layer of ink, placing it inside a large, folded sheet of paper and, finally, pressing it to produce two mirrored images of the specimen. At times finding themselves without artists to reproduce their findings, botanists tasked with the collection, preservation and transportation of ‘nature’ across distances became ‘desperate to preserve the likeness of plants and deeply worried about the fate of their herbaria’.32 Printing directly from specimens was a cost-efficient and easy way to document their discoveries; in addition, the results had greater visual and textural impact.

By the eighteenth century, European botanists considered direct printing to be the ideal medium to explore plant venation, as the technique allowed for even the most minute details of leaves to be reproduced. This appetite for accurate scientific images catalysed technological innovations and developments in nature printing over the next one hundred years. Yet the idea that rubbing was a technique designed to achieve ‘truth-to-nature’ was not always accepted by naturalists, some of whom believed that a faithful image was ‘emphatically not one that depicted exactly what was seen’.33 In time, the process of rubbing became an obsolete mode in visualising information in favour of a ‘reasoned image’ – that is, a drawing in the more traditional sense of the term.34

However, a handful of British botanists did consider nature printing to be an improvement on old methods of conveying graphic information about botanical specimens, inasmuch as it represented not only form with absolute accuracy, but also surface, veins and other detailed elements of superficial structure. Henry Bradbury (1831–60), a foremost practitioner of nature printing, highlighted in his account the properties of this technique in relation to the study of ferns. Bradbury singled out the sense of touch, rather than sight, in identifying particular British fern specimens. To back up this reading with evidence, Bradbury provided an interesting anecdote: he recounted the story of the little-known botanist John Gough of Kendal, who, having ‘become totally blind from small-pox when two years old, [...] so cultivated his other senses as to recognise by touch, smell or taste, almost every plant within twenty miles of his native place’.35 For Gough, as for Bradbury, nature printing supplied to the eye the same class of ‘positive impressions’ as those conveyed through haptic learning.

In the dark: feeling with fingers that see

The sense of touch has often been demonised, even banished, from the realm of ‘the visual’, considered to be a more ‘primitive’ form of sensing. As many scholars have pointed out, touch is fundamentally about space and presence, of ‘being present to the other’, or what Michael Taussig has called an ‘optical tactility’.36 During an online conversation hosted by Drawing Room, London, in 2022, Gill remarked that ‘you see much more clearly when you can’t see with your eyes’.37 Rubbing or printing directly from a specimen without the aid of sight is about ‘seeing with your fingers’, she continued.38 Switching from the mental and visual to the manual becomes a form of ‘sublimated fidgeting’ to enhance concentration on a task that is intellectually demanding.39 Gill’s comment recalls a line penned by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in which he associated the act of learning with the sense of vision, but above all with that of touch: ‘Seeing with a vision that feels, feeling with fingers that see’.40 In the daytime, the poet is guided by the luminous words and works of the ancient Classical philosophers, historians and playwrights: he devours their books, memorises stanzas and draws mental images. But at night, and in the presence of his beloved, the old masters are of little use and learning becomes a thoroughly tactile, feverish, intoxicating, even insomniac affair: the breasts and hips of his lover guide his hands, putting the eye to sleep. He gropes in the dark for an erotic impression that is patchy, anything but linear, complete or satisfying. Goethe’s words in relation to the powers of haptic learning and sensing resonate with Gill’s observations about the ignorance or inattentiveness that daylight vision can cause. Henri Focillon proposes a similar reading about the importance of the sense of touch in his text ‘In praise of hands’ (1934). He writes:

Knowledge of the world demands a kind of tactile flair. Sight slips over the surface of the universe. The hand knows that an object has physical bulk, that it is smooth or rough [...] The hand’s action defines the cavity of space and the fullness of the objects that occupy it. Surface, volume, density and weight are not optical.41

The enhanced sense of touch is key to tactile knowledge and can occur in a state of sleeplessness or pronounced and induced vigilance: insomnia. Jonathan Crary returned to Emmanuel Levinas when writing about this state: ‘insomnia corresponds to the necessity of vigilance, to a refusal to overlook the horror [...] it is the disquiet of the effort to avoid inattention [...] But its disquiet is also the frustrating inefficacy of an ethic of watchfulness’.42 Prolonged fits of absent-mindedness or insomnia are contiguous with forms of dispossession and social ruin. In this state of total depersonalisation, bumping into something or rubbing a surface in the dark can be a way to regain awareness.

This type of making is emphasised by Gill, who perceives vision to be not only unnecessary, but a genuine obstruction to her process. The blindness of insight that comes from the act of creating a rubbing captures the most ancient –and also the least visible – intimate traces of an object. The philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman extended this idea to compare rubbings to a form of sculpture; it is, in fact, the sculptural process par excellence, one that reveals ‘gestures’ themselves as fossils.43 Initially quoting Penone – ‘to create a sculpture is a vegetal gesture’ – Didi-Huberman continued, ‘it’s the trace, it’s the process, the power of adherence, the fossil of the completed gesture, immobile action, a waiting [une attente], a point of life and death’.44 Through touch, rubbings release a latent image as either ‘brief time periods (the passage of animals) or long time periods (geological formations) that have become hardened and compressed like charcoal [...] an imprint of time’.45

A final snake thread

How does one make sense of Gill’s Naga Doodles FIG. 10? It is difficult to treat such creations as straightforward doodles. Largely an adult preoccupation, doodling has been described as a ‘nomadic form of drawing’ and is typically associated with a state of distraction, produced to escape the tedium of a meeting or a phone call.46 It is often instigated by a need to withdraw oneself from time and space: a way to address the unconscious. And for artists, at least since the 1920s, doodling has been perceived as an activity that evades the professional, skill-related demands and constraints placed upon them.47

The Naga Doodles series draws attention to the act of seeing or, rather, not seeing, in two main ways: firstly, in terms of process as the making of each direct impression takes place without the aid of sight; and secondly, in how Gill confronts the viewer with the unseen and overlooked, the destroyed and forgotten. Of these ‘flattened’ snakes, Gill has noted that they were not initially her own discovery, but instead pointed out to her by a driver, who was knowledgeable about the local fauna. Of these crime scenes, she explained that:

Many of these roads if not most run through plantations. The variety and ecology of snakes has been deeply affected by the plantations, some gaining favour, and others being decimated, their habitats and sustenance gone. Most of the snakes I picked up are males. They need to find new territory upon maturing hence the dangerous road and highway crossings.48

The back-and-forth movement in Gill’s rubbings, between abstract forms that evoke a mythical beyond and the concrete, material reality of these torn bodies, reveals a paradox in our understanding of these works. The act of repetition in the process of producing an image indicates a deliberate elimination of spontaneity; intuition, as it turns out, is a false basis of creation. Yet, repetition can also be productive through its numbing routine, engendering the emptying out of the active mind to induce a state of reflective meditation. This shift suggests a dialectic between the deep absorption of a contemplative subject that might lead to the creation of these intimate and precisely rendered images and a collective, anonymous, creative potential, closer to the almost rigid process of mechanical printing. The senseless violence inflicted upon these once-mythical creatures exists along the same continuum as the violence done to the images. Furthermore, it relates to the taboo of killing an animal, a death that is not for the purpose of sacrifice. Gill’s very process undoes boundaries: to be in contact with the slimy is to ‘risk being dissolved in sliminess’, as Jean-Paul Sartre puts it.49 Quoting Sartre, Malcolm Bull adds ‘slime sticks to the fingers, so in the act of appropriating the slimy, the slimy possesses me, eliding the distinction between self and non-self’.50

In this series Gill tackles the intangible, pointing at things and creatures that ought to remain hidden, untouched and best left undisturbed. Rubbing these animal doodles offers Gill the most direct way to examine the unchecked violence of the ordinary, the banality of carnage. One might then be tempted to read these images as cyphers of past, present and future extinctions. Such cyphers compel Gill to sustain enough curiosity to notice the ‘strange and wonderful’ as well as the ‘terrible and terrifying’ – even the apocalyptic – that is the revelation of things hidden.51 Her ethnographic attentiveness is channelled through touch: pressure points, intimacy, slimy and sticky attachments. At once abstract and concrete, visceral and visual, Gill the augur and haruspex picks up densities, textures and colours as she impresses and moves her hands over bodies and dramas in the dark. The bleeding guts and entrails of a once awe-inspiring mythical creature, the cold-blooded king of beasts, might very well be the best place to start seeing with one’s fingers.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank her mother, Shelagh Burns, who introduced her to the principles of Mayahayana Buddhism, the sage Nagarjuna and Mucilinda, the kind snake. She would also like to thank Crofton Black and the two anonymous peer reviewers for their incisive comments and suggestions. Simryn’s patience, wisdom and wit undergird this essay; mistakes belong to the author.