Drawing on repair: Kang Seung Lee and Ibanjiha’s transpacific queer of colour critique

by Jung Joon Lee • June 2023. In collaboration with Drawing Room, London • Journal article

Introduction

The spring of 2021 was an especially difficult time for transgender and queer people in South Korea. Two publicly known figures, Kim Kihong (1983–2021) and Byun Hui-su (1998–2021) – who identified as trans non-binary and a trans woman respectively – took their own lives within ten days of one another. This was not an unfamiliar story, which invoked the trauma of socially invisible precedents in the trans and queer communities. They reacted with anger and grief, but social distancing mandates initiated during the COVID-19 pandemic made gatherings near impossible, preventing collective mourning.

This article examines drawings by two Korean artists, Kang Seung Lee (b.1978) based in Los Angeles, and Ibanjiha (AKA SoYoon Kim; b.1981) based in Seoul, dealing explicitly with these deaths and the process of grieving and remembering them. It explores possibilities for repair through their work, which is made against a sociopolitical backdrop of persistent anti-feminist movements, transphobia within radical feminist movements, historical catastrophes concerning members of the queer communities and racialised trauma. The divergent aesthetics in Lee’s and Ibanjiha’s work offers a transpacific, queer of colour critique. In his book Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color Critique, Roderick A. Ferguson defines queer of colour critique as an interrogation of ‘social formations as the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and class, with particular interest in how those formations correspond with and diverge from nationalist ideals and practices’.1 Following Ferguson, this article takes the critique as a heterogenous enterprise and centres transpacific non‑heteronormativity as a way to rethink both the global trajectory of queerness and the trap of identitarian oppositions in tandem.2 It focuses on the ways in which they invite audiences to reconsider latent alliances – whether between artists and their subjects, artists and audiences or artists of divergent aesthetic and epistemological practices – and how they are activated through grieving.3 It also aims to build alliances towards a mode of collaboration and reimagine a futurity that ‘draws on’ repair.

To grieve

Kang Seung Lee makes multimedia works that revisit the works and lives of LGBTQIA+ artists and activists. His drawings are often based on photographs, journal pages and magazine illustrations. In such works Lee extends intimate contact with individuals who lost their lives or their loved ones during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, or have died as a result of transphobic or queerphobic violence. For example, his series Untitled (Tseng Kwong Chi) (2019–20) is based on the photographic series East Meets West (1979–89) by the artist Tseng Kwong Chi (1950–90). Tseng was born in Hong Kong and was educated in France and the United States; he found his community in the Lower East Side neighbourhood of New York, in the 1980s, where he collaborated with such artists as Keith Haring (1958–90) and the choreographer Bill T. Jones (b.1952). Tseng died from AIDS-related illness and his photographs depicting his friends and loved ones are now understood as more than mere documents of the lives of lower Manhattan socialites; they are considered as collaborative projects.

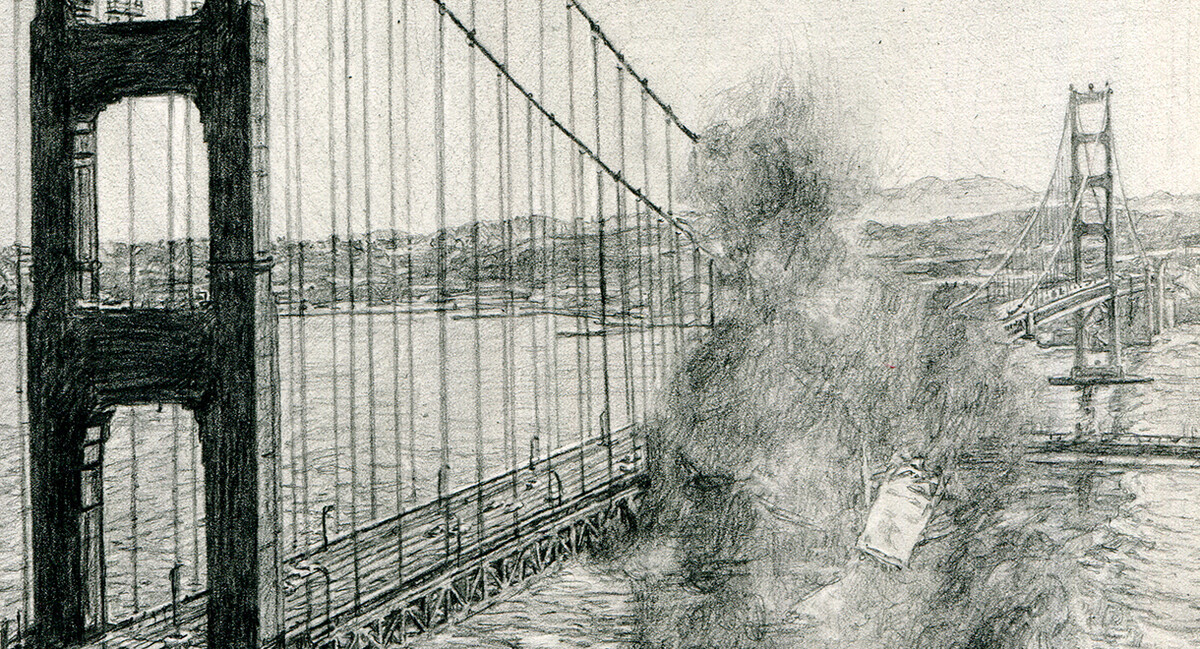

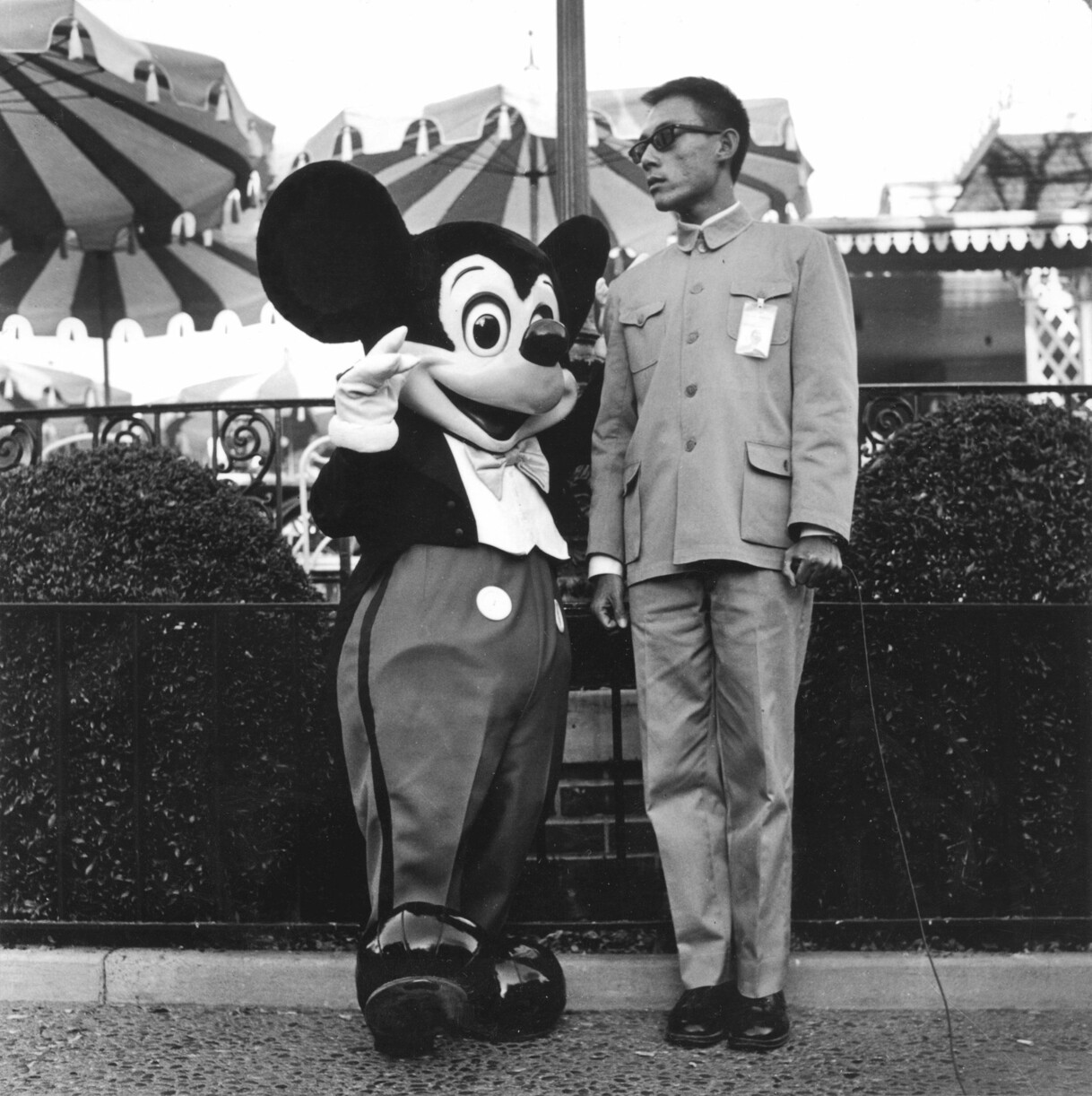

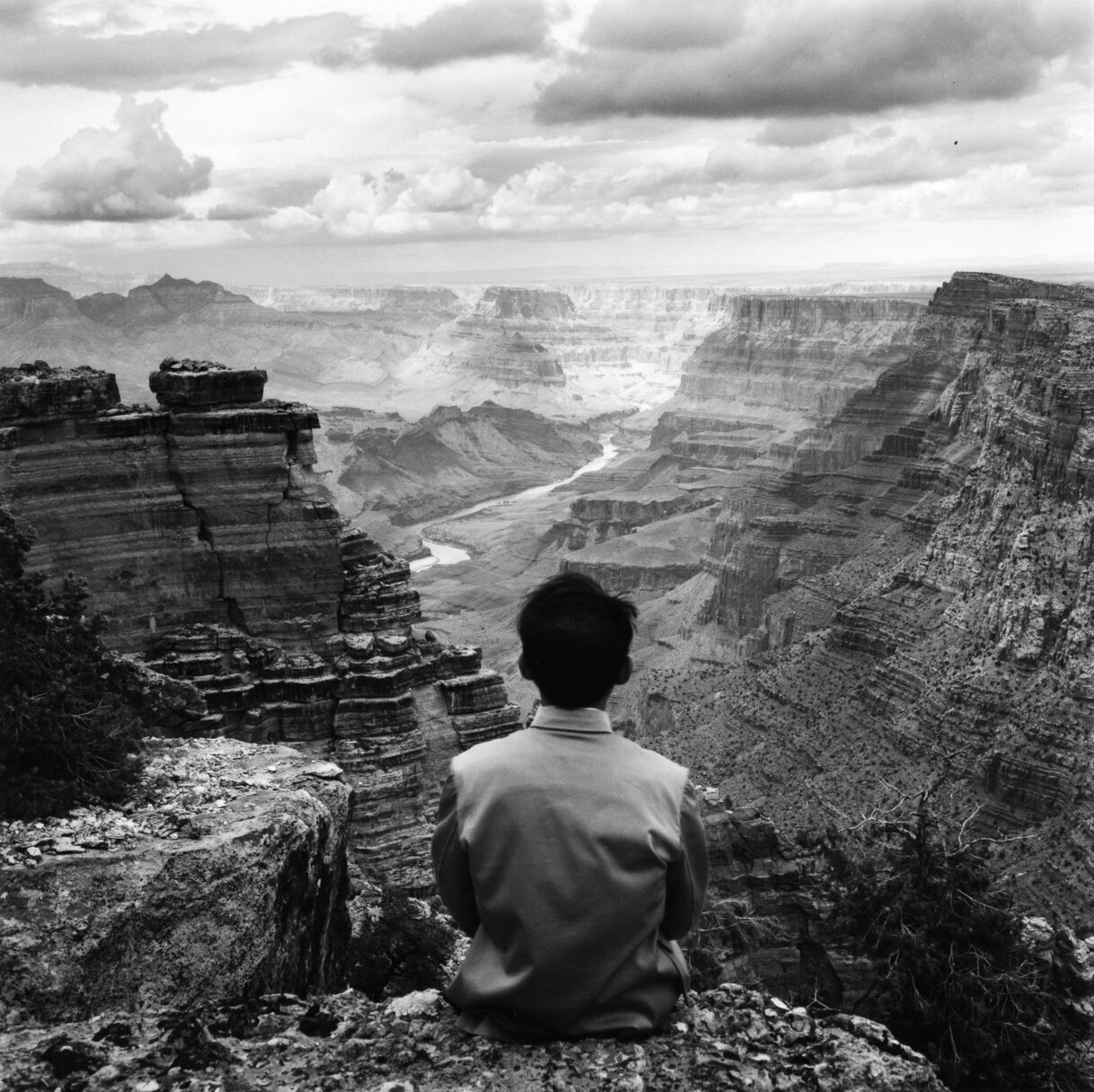

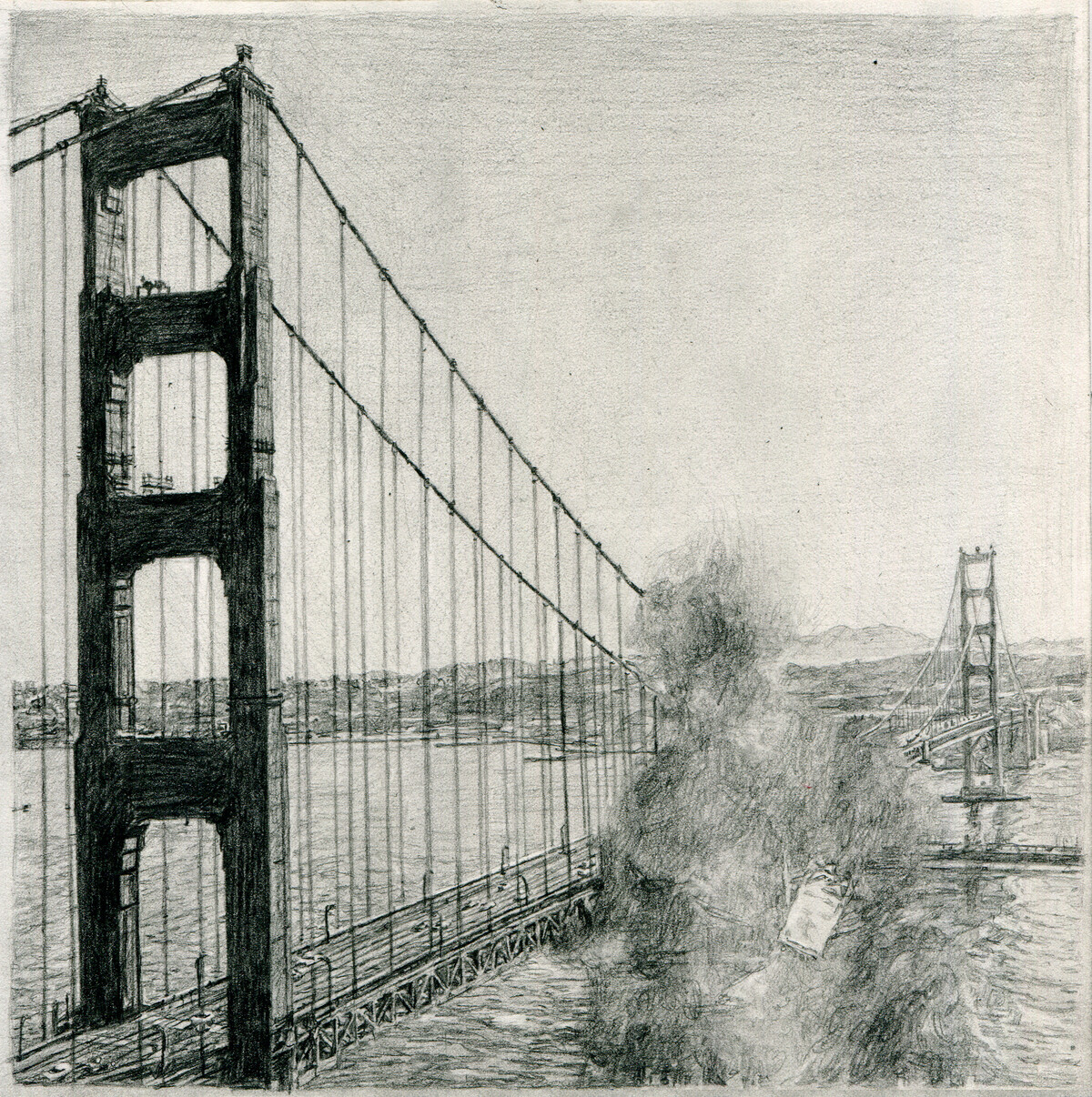

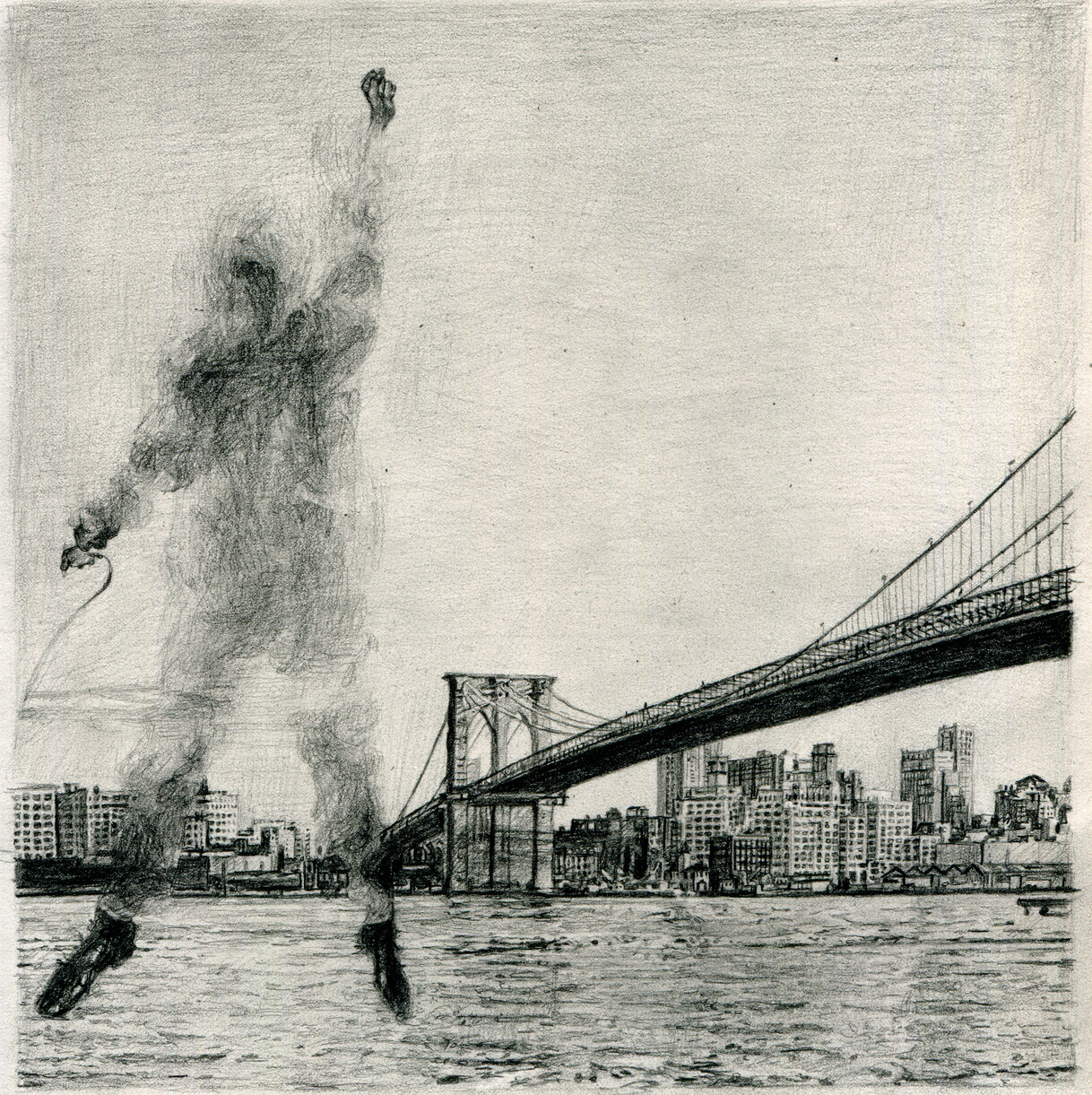

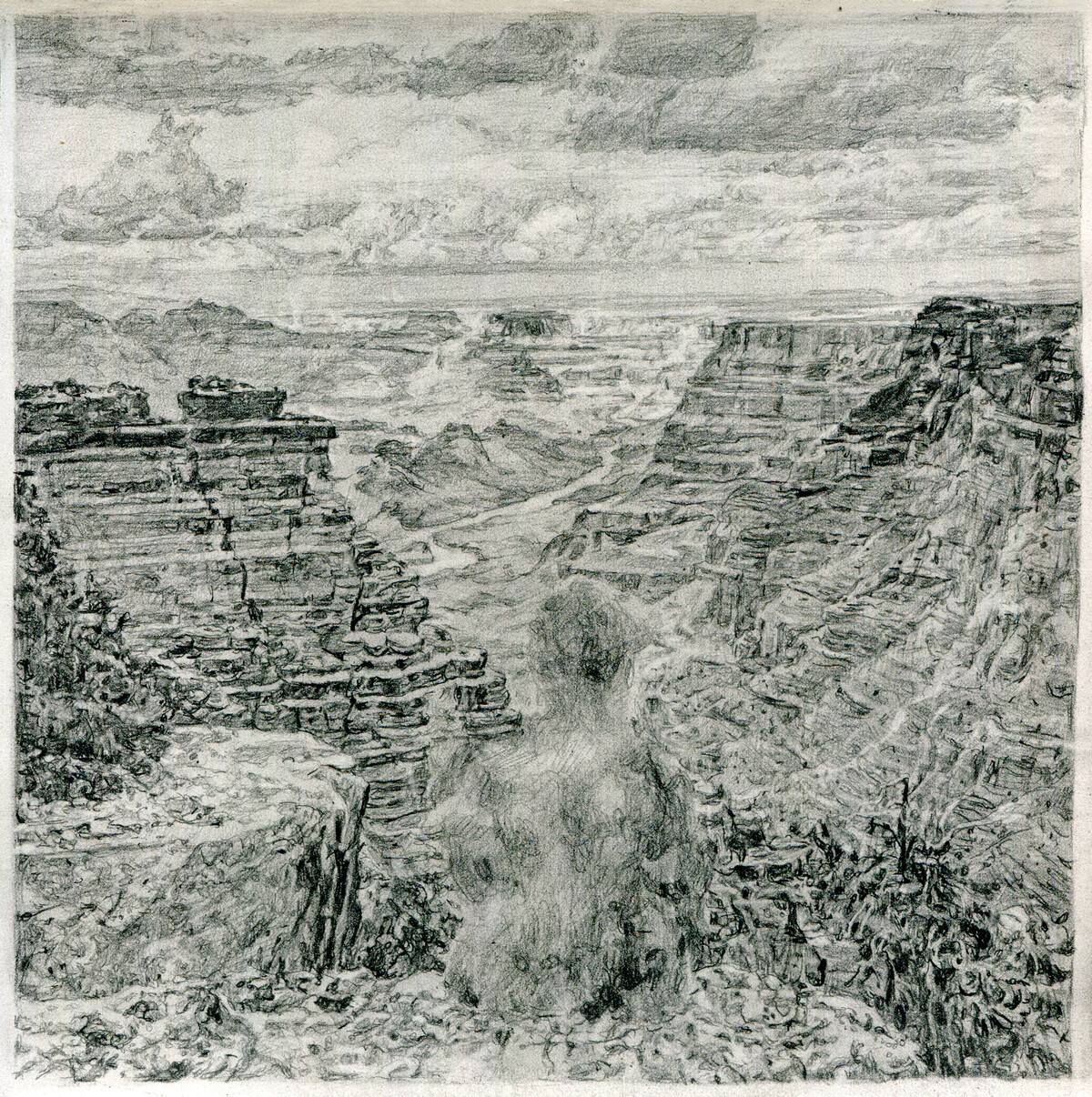

East Meets West comprises over one hundred photographic self-portraits, in each of which Tseng performs an imagined identity that has been projected onto him by non-Asians. He wears a plain grey Zongshan suit, or what a Western audience might know as a ‘Mao suit’, which he purchased in a thrift store in Montreal. Tseng noted that people reacted to him with greater respect and formality when he wore it, perhaps assuming that he was a Chinese dignitary. His appearance, signifying his Otherness for certain Americans, nevertheless, uprooted him from the land where he made his home. He exploited and explored this racist assumption in order to convey a sense of unbelonging and melancholia, depicting himself wearing the suit at various landmarks, such as the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco FIG. 1, Lincoln’s Memorial in Washington and Disneyland California, holding a shutter clicker in his hand FIG. 2. The series extended to such European landmarks as the Eiffel Tower, Paris, and Tower Bridge, London FIG. 3, and later North American National Parks FIG. 4. In aligning himself with iconic American scenes as a conspicuous foreigner, Tseng conjures both the futility of and yearning for belonging, even as that desire complicates his relationship with the past and present of the settler colonial state.4

Lee’s drawings of Tseng’s photographs involve a process of ‘unmaking’ Tseng’s body. In Untitled (Tseng Kwong Chi, San Francisco, California 1979) FIG. 5, in contrast to the crisp delineation of the photograph, Tseng’s figure has become an unrecognisable haze, except for the shape of the ID card on his chest. Although Tseng has apparently evaporated, his fake identification badge – which he made for the ‘dignitary’ character of the suit – hangs on like the impenitent force of an identitarian urge that othered Tseng. In fact, erasure is critical in Lee’s series: while the ID card remains conspicuous, the photograph that would represent his visage has also been erased. The recognisable hatchings and cross-hatchings of graphite contrast strikingly with the more realistic rendering of the bridge and the landscape in the background. The erasure, or abstraction, of Tseng’s figure turns his presence into an apparition; he becomes a spectre that haunts American identity politics, which buttresses the country’s colonial legacy through the racialisation and meritocratisation of belonging and unbelonging. In this way, the process of erasing Tseng’s figure opens a dialogue with and about the original work, commemorating Tseng’s metaphorisation of his disappearance in and against the American landscape. Moreover, Lee’s homage to Tseng is an acknowledgment of the intergenerational trauma of the AIDS epidemic. As Gemma Anderson-Tempini has remarked, his drawing process ‘challenges the impulse to attach, name and possess and to fade the present into the past prematurely’.5 Rather than recall Tseng’s work as a document of the past, Lee’s drawings re-activate the relationship between memory and embodied experience.6 In this way, Lee grieves the deaths and history of queer Asians in the United States, in particular that of Tseng, who died almost thirty years before this series was created.

Lee’s grieving has travelled across the Pacific. In Lee’s major solo exhibition Briefly Gorgeous (Chamsi ch’allanhan) held at Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, in 2021, the artist included a graphite-on-paper drawing of the aforementioned Byun Hui-su and Kim Kihong FIG. 6.7 A music teacher turned activist and later a politician, Kim Kihong died by suicide in February 2021. They began their activist work when the school they taught at on the South Korean island of Jeju terminated their position due to their ‘feminine manner and appearance’.8 As a member of the Green Party, Kim tried to gain a seat in the National Congress as piryetaep’yo (proportional representation) in the 2018 regional and 2020 general elections. In 2020 however, they dropped their candidacy, and issued a public apology relating to backlash about the online comments they made against women a decade earlier. Kim ended their life five days after a Seoul mayoral candidate argued on television for ‘the right to not see queer parades in the city’.9

While serving mandatory military service, Byun, who is depicted on the left in Lee’s drawing, underwent gender confirmation surgery. Despite having consulted with her superiors beforehand, she was forcefully discharged upon returning to the service. Although the National Human Rights Commission of Korea recommended her reinstatement as a servicewoman, the military court dismissed the case. Byun filed a legal suit against the military; she ended her life in March 2021, a month before she was due to appear in court. Despite the work of South Korean LGBTQIA+ communities and support groups, she was exposed to a flood of transphobic reactions and threats, both online and offline. Her death was considered by the public to be, in part, a result of the impossibility of her battle with the military. Indeed, while the Regional Court of Daejeon posthumously ruled Byun’s discharge unlawful, legally rescinding the discharge in October 2021, the military refused to acknowledge that Byun died in the line of duty.

Lee’s drawing is based on photographs: Byun, in three-quarter view and wearing her military uniform, gazes upwards to the right, whereas Kim looks directly at the viewer with a large smile on their face. The floral patterns on Kim’s dress and the camouflage pattern on Byun’s uniform are closely detailed. This is a key characteristic of chŏngmilhwa, a genre known for its hyperrealistic rendering of the subject-matter. The different positions of the two figures purposefully demonstrate the juxtaposition of the source photographs, which is further emphasised by the cropping of Kim’s shoulder, abutting Byun. In addition to accentuating the disparate nature of the source material, the treatment in the drawing highlights Lee’s direct approach to commemorating their deaths. Moreover, the immediacy of the representation – both in temporality and proximity – also point to queerphobia and transphobia as constant threats to the lives of LGBTQIA+ people in South Korea.

Although the emphatic presence of realistic detail in the double portrait is superficially antithetical to the erasure in Untitled (Tseng Kwong Chi), they both rely on a coherent conceptual and technical methodology. Of course, whereas Lee’s act of erasing Tseng is a direct response to East Meets West FIG. 7, the photographs Lee used as reference points for Byun and Kim were taken by others, for other purposes. Tseng delves into the conspicuousness of the invisible Other in the American landscape, which Lee engages with in his treatment of the photograph through drawing FIG. 8. By contrast, in representing Byun and Kim, such a methodology of erasure would only induce more pain, and thereby run the risk of turning both subjects into the spectres of homophobia and transphobia. Lee leaves the drawing of their portraits crisp and clear, still knowable and rememberable.

And yet, for the Seoul-based artist Ibanjiha, encountering Lee’s drawing in 2021 was not an easy experience. Ibanjiha was not ready to commemorate the deaths of Byun and Kim in a space dedicated to art, while still mourning their losses.10 However, Ibanjiha acknowledges that the ways in which the viewer is challenged by the temporality and proximity of Lee’s representation is an important aspect of grieving queer deaths together.11 In particular, ‘different ways of grieving and remembering should be allowed to co-exist’ precisely because the regime of memory dominated by heteropatriarchy legitimises certain ways of remembering and not others.12 Lee’s work draws attention to how one mourns queer deaths in public and how this blurs the seeming dichotomy between grieving and memorialising, and thus their epistemic hierarchies – in this case through the mimetic representation of the deceased in the public space of an art gallery.13

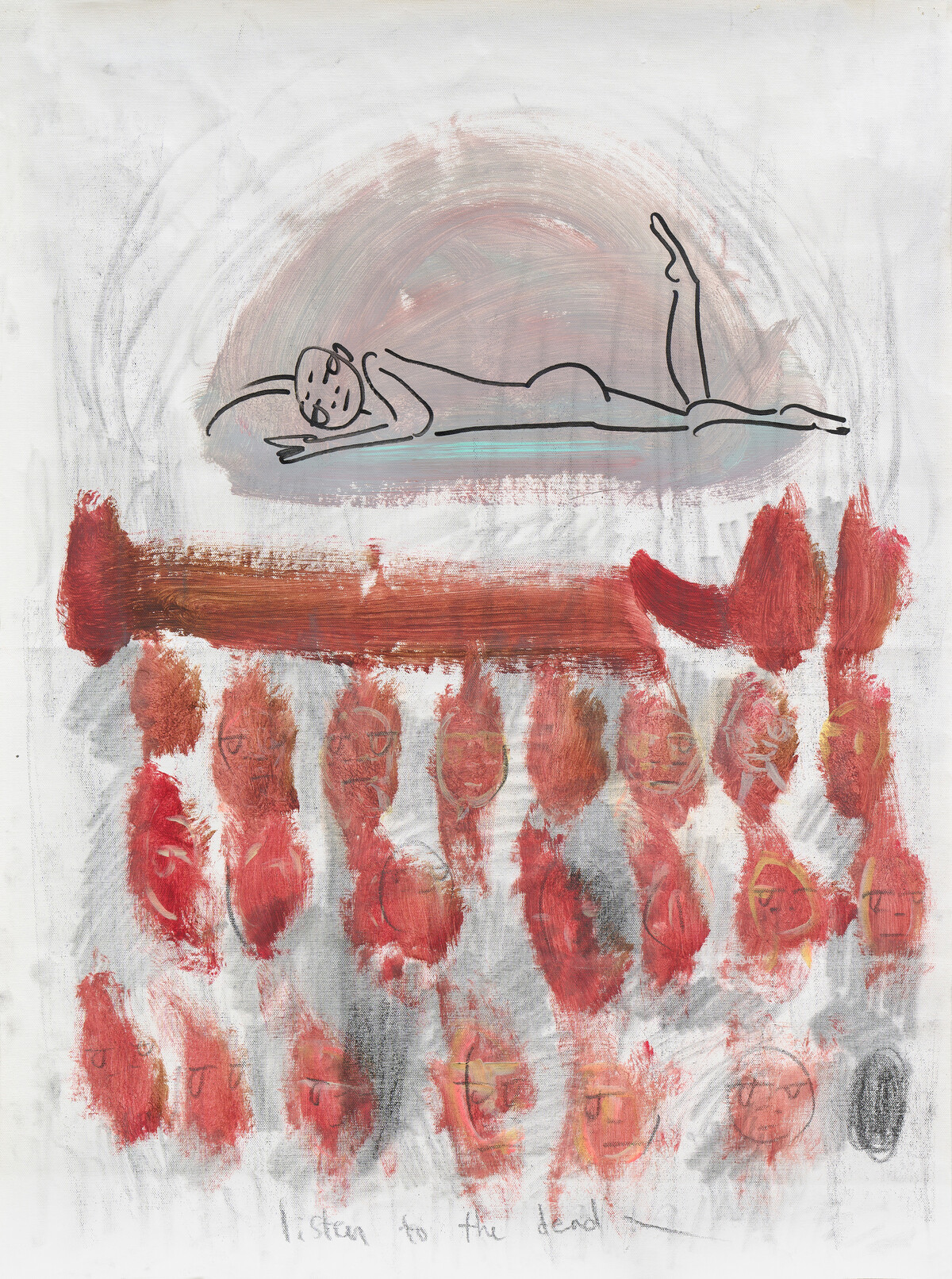

As such, like Lee, Ibanjiha responds to recent deaths, mostly of people unknown to the general public, with drawings and paintings. In Untitled (Listening to the Dead) FIG. 9, an androgynous figure – a signature of Ibanjiha’s work, which Ibanjiha sometimes refers to simply as ‘the body’ – is drawn with a marker pen on canvas. They are lying down on their stomach, with their head turned and their ear touching the ground. Pictured underneath is an underworld in which dead people appear as floating heads with indistinct facial features, rendered in a brownish red. The main figure is surrounded by a semi-circular shape, which is identifiable as a burial mound covered with grass – a common burial practice in South Korea. The translucency of the paint situates the figure both inside and outside of this mound; thus, they are listening to the dead and talking to the living.

In their description of the work, Ibanjiha writes: ‘queer deaths are rarely acknowledged and are buried too quickly. I still need more time to listen to the dead. There must be more to hear from the dead’.14 This figure can therefore be understood as Ibanjiha making an effort to get closer to the dead and hear the words that have arisen from their deaths. This recalls Sara Ahmed’s feminist ear, which she defines as the act of listening to what heteropatriarchal society deems to be ‘complaints’. In her book Complaint!, Ahmed set out to grant ‘complaint a hearing, by giving room to complaint’.15 Ahmed insists on doing the exhaustive but necessary work of active listening and care since ‘to be heard as complaining is not to be heard [… it] is an effective way of dismissing someone’.16 Hence, listening to the complaint – of the dead, of the oppressed – becomes an act of affirming the existence of the complainer. Ibanjiha not only lends an ear in the drawing, but by doing so, realises a life, and afterlife, of the deceased.

To collaborate

The clear differences in Lee’s and Ibanjiha’s representation of death are, of course, indicative of the very nature of aesthetics. However, what is also at stake here is where and how such aesthetics expose the disjuncture of ‘queerness’ between different cultures as it makes its global trajectories.17 Despite the disparity between Lee’s and Ibanjiha’s drawings, the two artists are nonetheless unified by their efforts to explore the notion of ‘queer’ as neither a universal identity nor a white homonormative ‘foreign’ production. Moreover, each of their approaches are intertwined with – and often superseded by – the matter of survival in their own contexts: Kang Seung Lee as a queer Korean man in the United States, where East Asians have increasingly been the target of violent attacks since the COVID-19 pandemic, and Ibanjiha as a queer artist in South Korea, where the surge of anti-feminist and trans exclusionist movements are exacerbated by anti-disability and anti-immigration sentiments.

Lee’s work often refers to intergenerational and interspecies care. For example, a 2019 graphite drawing FIG. 10 depicts a small cactus plant that Lee’s friend and collaborator Julie Tolentino has been caring for, shown alongside screenshots of text messages they exchanged.18 The cactus is a cutting from a larger plant that belonged to Harvey Milk, who was California’s first openly gay elected official and served on the Board of Supervisors of San Francisco until his assassination in 1978. Since then, the cactus plant has been cared for by various people, including Tolentino, who received it from a friend who works at the University of California, Los Angeles, in Special Collections. The drawing of Milk’s cactus is thus not simply the work of a lone artist making life-like renderings in his studio, but a longer-term collaborative work that builds upon mutual care and dialogues between the living and the dead.

Perhaps because the skilled nature of Lee’s technical renderings initially holds the viewers’ attention, the graphite drawings are not immediately apparent as products of collective effort per se. The curator and writer Gökcan Demirkazik has discussed the ways that Lee complicates the logocentrism of mimetic representations in Untitled (Tseng Kwong Chi), considering the drawings as his ‘medium of translation’:

Each time Lee transliterates a shaded area in a Tseng photograph into a series of hatchings and cross-hatchings, he exercises the agency of replacing what is indexically ‘there’ in the photograph with an approximation modulated by his own hand, while allowing idiosyncratic flourishes that respond to the spirit of each image. In this way, Lee’s works not only reassert marginalised figures or bodies of work from the point of view of history-writing into collective memory, but they also enter into a full-bodied creative dialogue with their subject matter.19

Collaboration does not only refer to working on a project with others. In the case of Untitled (Tseng Kwong Chi), Lee engages a dialogue with the deceased artist by responding to his ‘placemaking’ in the American landscape and putting ‘himself in their proximity’.20 This intergenerational grief and melancholy itself becomes a form of collaboration.

Ibanjiha, on the other hand, plays a public role that must be personally and artistically navigated. The recurring figure in their drawings and paintings – androgynous, bald, naked, slippery, bouncy, jolly, spontaneous and loving – represents both the singularity of Ibanjiha’s persona and the collectivity and diversity of their queer fandom. Ibanjiha is one of the few openly queer artists in South Korea. Born SoYoon Kim, they took as their name a word that combines Iban 이반 (queer) and Banjiha 반지하 (underground apartment), referring to ‘the mode of living characterised by a lifetime of artmaking in precarity’.21

Although Ibanjiha is highly visible, years of attempting to garner a wider viewership and secure funding from national arts foundations and institutions have taken their toll. After a decade and a half working on the fringes of the university system and art-world in South Korea, in 2019 Ibanjiha conceived what they felt would be their final performance: Ibanjiha 2019: The First and Last Human Rights Solo Concert in Seoul. However, paradoxically, this performance revealed that Ibanjiha had a growing number of supporters and fans, many of whom were young queer creators themselves. The event was subsequently made into a live concert album, in turn leading to such projects as their own live show on YouTube, Ibanjiha 24-Season, following the Korean traditional calendar that divides the year into twenty-four seasonal periods, performed between 2020 and 2021. As a result, Ibanjiha began to renegotiate how they engage and interact with others as part of their practice. Having experienced professional collaboration turn into exploitation in the past, rather than work with other artists or creatives, Ibanjiha instead collaborates with their supporters and fans.22 Ibanjiha’s performances and YouTube shows engage directly with audiences and often cannot be made without audience participation. The queer affect that arises in such work is mutually beneficial. For example, Ibanjiha 24-Season responded directly to recent queer and trans deaths, setting out to establish a supportive community.

Such collaborative exchanges between Ibanjiha and their fans are openly reciprocal in other ways too. Affectionately nicknamed kamt’ae (ecklonia cava; an edible marine brown alga species), the fans pay a small amount of money termed a munhwahyet’aekpi (cultural benefit fee) to Ibanjiha so that they create multidisciplinary works, such as YouTube live shows, in-person performances and visual and sound works. Most Korean artists without gallery representation, university professorships, or indeed inherited wealth, depend heavily on public funding. Moreover, even gallery representation, museum exhibitions and academic positions all involve public funding to some extent, and are similarly dependent on pedigree, prestige and patronage. Ibanjiha, however, believes that public money cannot viably be spent on art that substantially challenges heteropatriarchy, or even rattles the cage set aside for queer artists in the public art sphere. Instead, this mutual support system bypasses those of contemporary public culture. Furthermore, Ibanjiha is upfront and transparent about their exchange, whereas most normative artist-viewer transactions are mediated by institutions, regulated in private and therefore placed out of easy public reckoning.

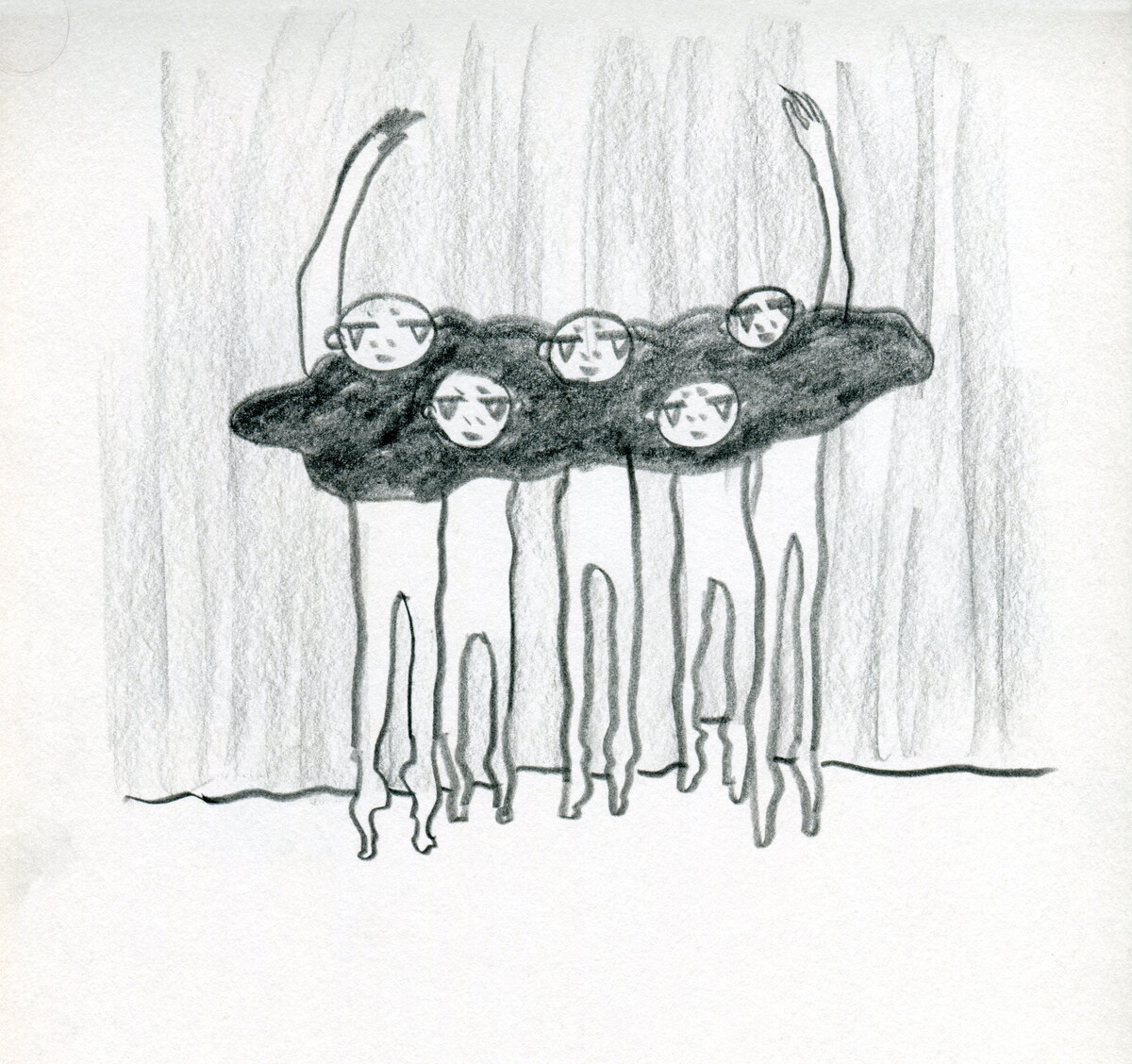

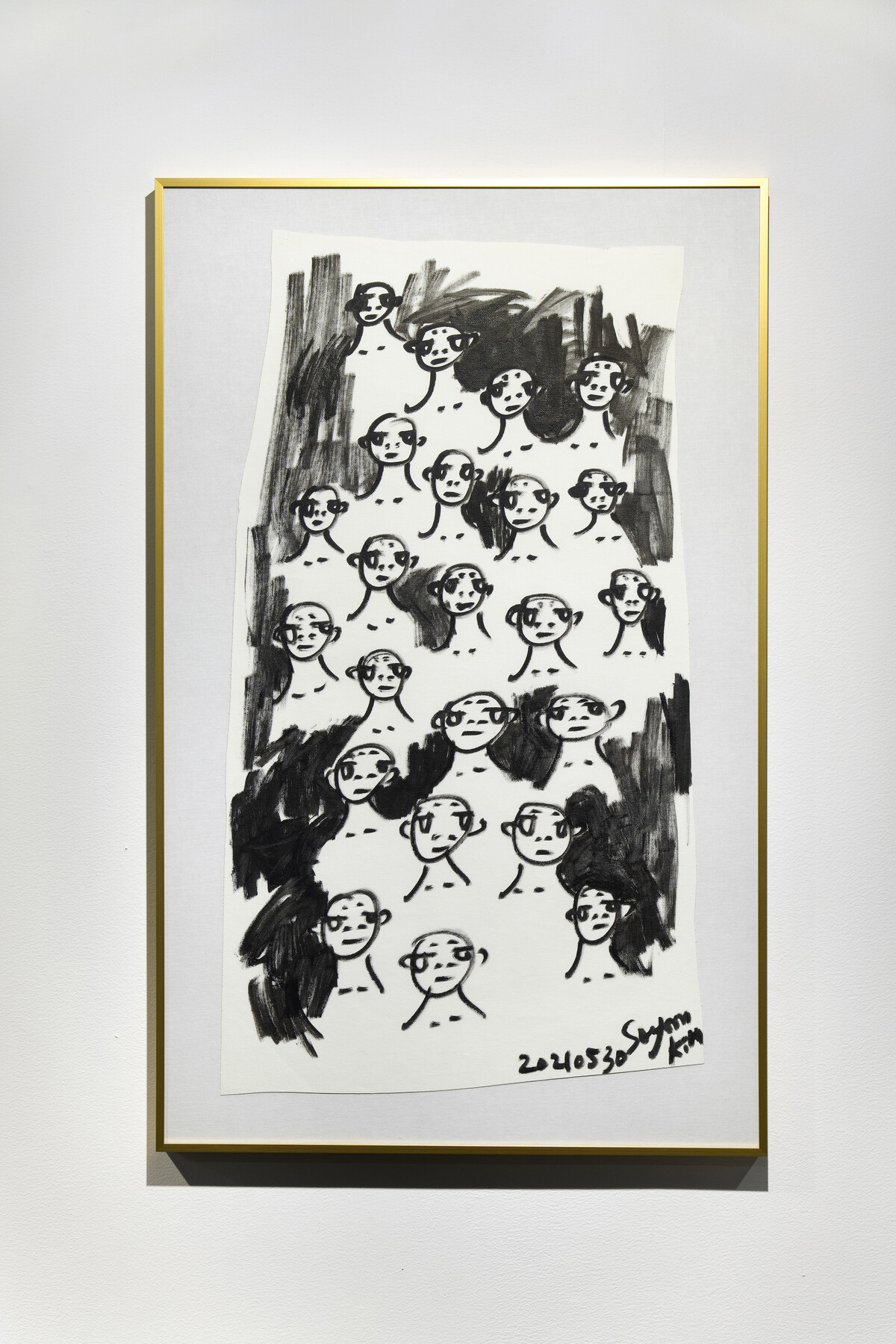

In 2021 Ibanjiha published their first book, Iutchip Ibanjiha (Ibanjiha, A Queer Next Door). It details their experiences living with the trauma of familial and societal violence rooted in homophobia and misogyny. Crucially, it carries a cathartic force, which also disidentifies with heteropatriarchy and homonormativity; it was an unprecedented subjectivisation in queer and non-queer Korean literature alike.23 The book also includes a number of drawings, paintings and animation stills that all reference the artist’s signature ‘body’, as seen in Listening to the Dead. Having evolved and adapted over the years, this figure is at once Ibanjiha themselves navigating a fast-paced society – at least, when it comes to neoliberal ‘advancement’ – and at the same time synonymous with the collective energy of Ibanjiha’s fandom. The figure is explorative, light and flexible; it is situated in mostly ambiguous, but often colourful, surroundings. They are multiple yet singular, vulnerable yet carefree, cynical yet caring FIG. 11.

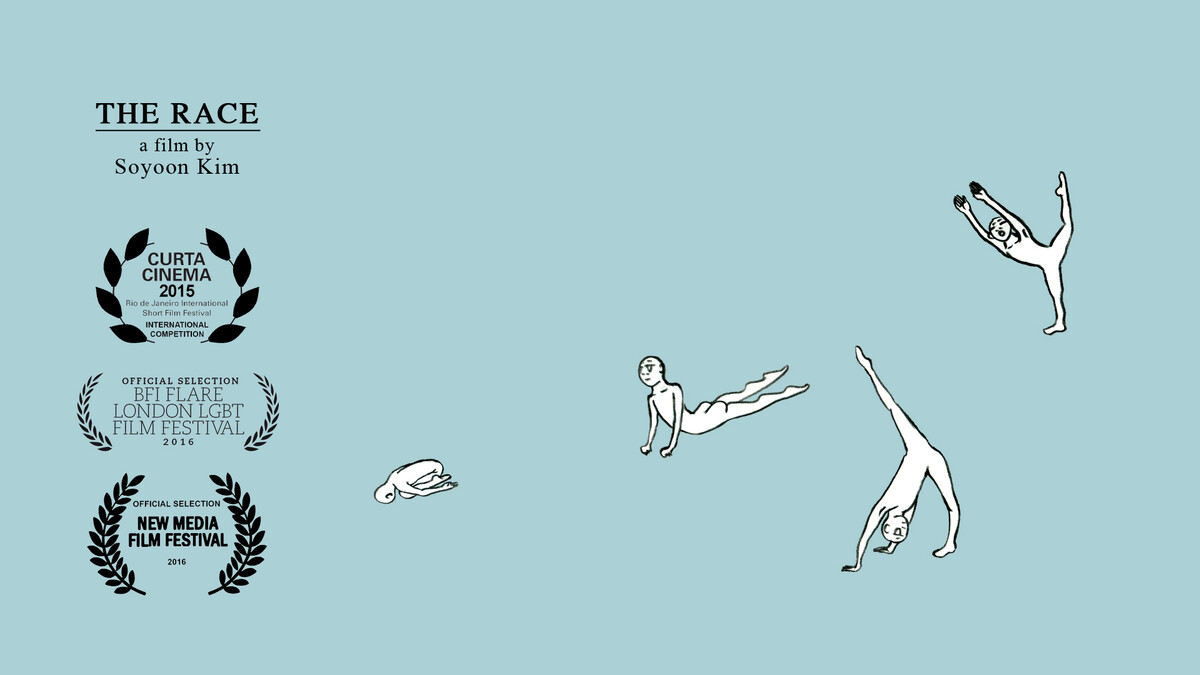

This adventurous figure also travels between different media, from the book to performance, drawings exhibited in galleries and animation FIG. 12 FIG. 13 FIG. 14. These figurative drawings lose their medium specificity in Ibanjiha’s disidenficatory queer tactics, which renegotiate – and ultimately disrupt and disidentify – with a majoritarian world that forces the formation of minority subjectivity within the phantasm of normativity.24 Such tactics yield flexibility for ‘manoeuvring’ in society where forms of violence against people – those deemed outside of heteropatriarchal and neoliberal ideals – have been increasing.25 Although Ibanjiha themselves emphasises how important working on paper and canvas is to their practice, the digital turn was inevitable, notably a result of lack of space and storage, again recalling the meaning of their namesake.26 The flexibility of Ibanjiha, and their figure, across mediums, can be seen as a parallel to the ways in which Ibanjiha manoeuvres through the world. They ask what it means to make signifiers of queerness in South Korea, where queer theory is both useful and harmful: useful in its critique of homophobia, and harmful for its erasure of the history of imperialist consumption and exploitation of non-Western subjects – from its epistemological upperhand position in both the critique and erasure.

For Lee and Ibanjiha, collaborative approaches to their subject-matter are both methodological and representational modes of artmaking. Lee, for example, partakes in acts of interspecies communal care, sustaining and celebrating his queer kinship; he then translates this collectivity into graphite drawings and multimedia works. On the other hand, the relationships that Ibanjiha has built with their fans is critical to their work, and collaboration is established through mutual trust and affection. In their own ways, both artists demonstrate that artistic collaborations are not limited to relationships between artists or artists and curators; they can happen in unexpected places, between the living and the dead, the artist and their fans, on paper and in YouTube shows.

To repair

The larger context of Lee’s and Ibanjiha’s drawings on recent deaths of LGBTQIA+ people demonstrates how both artists work with and against ‘the global career of queerness’, as well as the relational dynamics between the aesthetics of grieving in South Korea and across the Pacific.27 Neither Lee nor Ibanjiha take queer theory – whether as a global epistemological project or ‘local’ North American discourse – as a major guiding principle of meaning-making for queerness. Nonetheless, recent debates in the global circulation of queer theory resonate with the projects outlined here.28 For Lee, the very concept of globality itself is problematic as it assumes a homonormativity within the United States, which is exacerbated by the issue of defining ‘queer Asia’ – or queer Korea for that matter – to act as a counter-epistemic project to the American-born queer theory.

Shinsuke Eguchi has considered how ‘the alternative cartography of queer Asia that decentres Western queer knowledge production may obfuscate complexities and contradictions of (transnational, intercultural) Asia’.29 Eguchi reflects on their own struggle bringing their ‘embodied knowledge’ into ‘the intellectual production of queer Asia’. If the transpacific flow of queerness creates a queer Korea – arguing for the ontological formation of ‘homegrown’ queerness – it is equally critical to be aware that counter-ontology nevertheless operates within the differences homonormativity creates. This is compounded by the way that ‘homeland’ is often romanticised, without considering how ‘home’ continues to be reconfigured through ‘Intra-Asian cultural flows of racialisation, empire, regionalisation and capitalism that alter, shape and reinforce political rivalries, economic competitions and historical struggles complicat[ing] temporal and spatial specificities of intraregional interpersonal interaction process’.30 That ontology remains bound to the colonial production of binary subjectivisation foregrounding the epistemology of difference.

What, then, is possible for the ontology of queer Asia? Eguchi, struggling to navigate a way out of ‘Asianness’s impossibilities in the White, Western colonial past and liberal capital present’ asks if recovering the ‘nuances of queer Asia-ness that have been already erased by ongoing histories of colonisation’ is even possible.31 What would it mean to ‘recover queer Asia-ness’ outside of Asia, when the erasure itself has forged a counter-positionality of queer Asia, even as working against and with the binary has shown the limits and possibilities of the global trajectories of queer theory? Lee and Ibanjiha do not attempt to reconstitute the erased Asianness or Koreanness – or queer Asianness or Koreanness per se – and certainly not in the form of liberal capitalist desire that further Orientalises such identities. Rather than recover what has been lost or erased by the colonial, hetero- and homonormative urge to represent ‘queer Asianness’, the works of Lee and Ibanjiha, as Ferguson puts it, ‘shed light on the ruptural components of culture, components that expose the restrictions of universality, the exploitation of capital and the deceptions of national culture’ in and outside of Korea and the United States, giving a transpacific critique.32 Through this critique in their drawings, Ibanjiha and Lee also reimagine the work of repair in their own ways.

In Lee’s Untitled (Tseng Kwong Chi), Tseng’s ghostly traces – a cloud of smoke – become a refusal to completely disappear and be reborn as a kind of authentic queer Asian body joining the effort to resuscitate the subject of Orientalist gaze. Rather, the lingering cloud indicts and obfuscates the Orientalist gaze, undoing the perpetual Othering of that body. The spectral figure demands that viewers join the dialogue between Tseng and Lee. In reference to the later landscape photographs Tseng took, in which the artist’s body almost disappears in American landscapes around him, Lee has written of ‘a big contrast [in comparison] to his earlier East Meets West works where his body is always on the foreground with his “visitor” badge pronounced. I wonder if this change comes from his realisation that we all are permanent visitors here. One thing for sure is that he was no longer feeling otherness in these pictures’.33 Here, Lee grounds Tseng’s exploration of the settler colonial landscape and his own positionality within that landscape, while probing the very desire for reconstituting an Asian queer subjectivity in the settler colonial state. In his affirmation that Tseng was ‘no longer feeling otherness in these pictures’, one senses Lee’s own desire to free Tseng from the question of belonging: white supremacy uproots him from that landscape, but in the settler colonial state, all settlers are an uninvited ‘permanent visitor’.34

Hence, Lee’s drawings do not try to ‘recapture, remake and revive already erased nuances of queer Asian-ness’.35 Instead, they problematise such ideas and create transpacific and transtemporal connections, by employing, quite literally, the aesthetics of erasure. Lee’s repeated, careful renderings and erasing of the figure of Tseng Kwong Chi provides the viewer with something other than the binary of his presence or absence. The traces in the drawing manifest as a stubborn afterimage that lingers, like smoke that burns from incense at funerals. Lee states:

I would like to believe that my work – graphite renderings of Tseng’s works with his body replaced with a cloud of smoke – is about many things, not only about loss and mourning but also about the tenuousness of presence. I would like my work to question the erasure of others who came before and remain unseen, to generate conversations about the space that holds intergenerational connections and care and to be an invitation to reimagine invisibility as potentiality.36

Thus, the repeated gesture of making and unmaking is a way to engender intergenerational conversations, connections and care.

In a different way, Ibanjiha also reaches out to others mourning queer deaths and brings them together. In their performance-painting projects, their ‘feminist ear’ has been realised in live mixed-media sessions with audience participants. For example, in VIP: Visiting Ibanjiha Professionally FIG. 15, which was staged at Ibanjiha’s Residency Goyang Studio at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), Goyang-shi in 2022, Ibanjiha provoked and conversed with audiences about what it means to ‘perform’ a painting together engrossed in queer affect, while making marks in response to their interactions. Similarly, in another performance-painting project, The Word of Ibanjiha (2022–ongoing), Ibanjiha and audience participants explore the (im)possibilities of translating terms of queer theory from English to Korean.37 Here, words are spoken that hold context and tension in both English and Korean; working through the affective charges of queer meaning-making, the group thus invents their own ‘queer language’ in Korean. The affect that arises in the collective exploration is then ‘translated’ into the performance of drawing and painting by Ibanjiha. This work is also grounded in Ibanjiha’s critique of heteropatriarchy and misogyny in South Korea. From here, Ibanjiha interrogates the postcolonial and neocolonial conditions of queer life and intellectualism outside of the West. In these collaborative works, the tensions in and the desire for ‘authenticity’ in queer Korean thoughts become a critical material. Such a desire is itself a ‘cruel optimism’, to use Lauren Berlant’s words, which may repeat a colonial essentialist imagining.38 Thus, Ibanjiha seeks to undo the colonial trappings of an intellectual envy and inferiority complex.

Moreover, Ibanjiha’s critique is not limited to what occurs inside the works of art. The financial arrangement between Ibanjiha and their kamt’aes is both another transgression against normative heteropatriarchal systems and a means of asserting a reparative approach to artmaking. As Ferguson discusses, capital at once racialises labour and genders race, while also challenging heteropatriarchy by creating excess labour and values that it deems disruptive and disorderly to its logic.39 Exposing how heteropatriarchy expels what does not conform to the established systems, Ibanjiha’s queer art of mutual survival disrupts the technology of contemporary art production and consumption.40 Still, the transactions between Ibanjiha and their kamt’aes – which, after all, it is still a system of patronage – might seem aligned with the self-reliance model promoted by neoliberalism. But, indeed, their collaboration has forged a disidentificatory funding system, one that adopts the self-reliance model only to turn it into a refusal of being erased or forced into meritocracy. The artist’s funding system is also, as the scholar Imane Terhmina posits, a collaboration that rebuilds relationships between different people and renegotiates the bonds between them, especially those who are left with the affective charge of loss, as they work towards repair.41

Ferguson contends that queer of colour critique in relation to the Global South was not intended ‘to mobilise it for positivist ends’, but ‘to forestall logocentric claims, ones that would claim to capture the empirical essences of race, gender and sexuality’.42 Addressing the history and politics in the ‘global trajectory’ of queerness, Ibanjiha’s drawing performance reroutes the trajectory and subverts the logocentric claims made on the other side of the Pacific. A cathartic affect arises in the collaborative nature of the performances; they can only unfold through uncertainty, exhilaration and, occasionally, anxiety about challenging the certainty imposed by logocentrism. ‘Imagining coalitions within and outside that domain’, to use Ferguson’s words, becomes possible through Ibanjiha’s performance as a queer of colour critique.43

The works of Lee and Ibanjiha complicate the medium specificity of drawing and the identitarian representation of the queer of colour and non-Western queer subjectivity. By lending a feminist ear to the dead and the living, creating a space for grieving and exploring collaboration as a way to do so, they ultimately instantiate queer kinship and dialogues across generations and geographical distances. They reimagine reparative artistic experiences, which in turn generate conditions in which audiences can join in a recovery from the harms of anti-feminist, queerphobic and transphobic violence. Across drawing, performance, painting and installation, their collaborations do not culminate in objects, but are an invitation to the audience to join in listening to the dead: to Tseng, Byun, Kim, Milk and many more, and – although long and precarious – to collaborate with them in the work of repair.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Ibanjiha and Kang Seung Lee for their generosity and thoughtful conversations. Thank you also to the 2022–23 fellows of the Society for the Humanities at Cornell University, Ithaca NY, for their feedback on this manuscript. Thank you especially to Imane Terhmina for her insightful comments on grieving as a process of justice and alliance-making and the ‘ever-shifting and provisional re-activation of the affective charge of loss’.