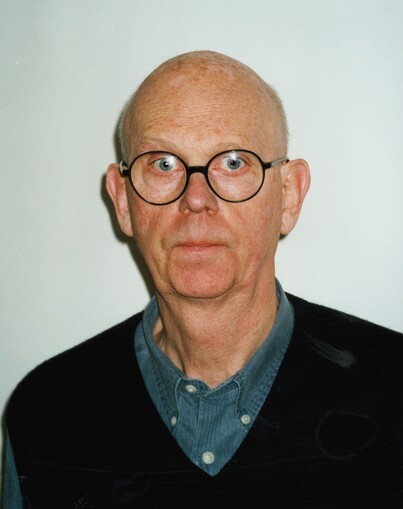

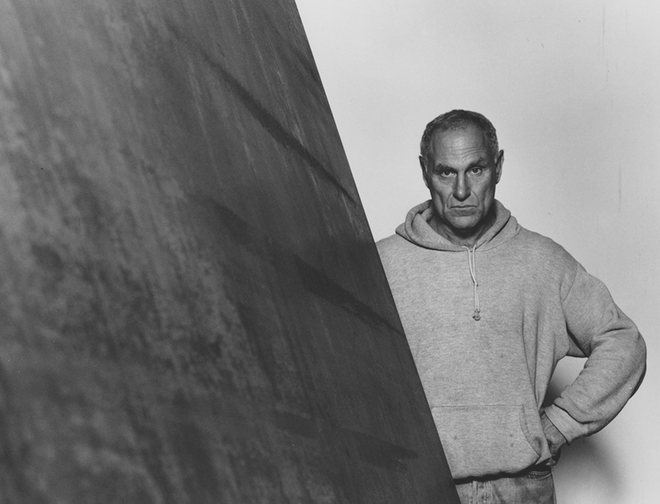

I first met Claes Oldenburg FIG.1, who died at the age of ninety-three on 18th July 2022, while researching an essay for his retrospective mounted at Mumok, Vienna, in 2012, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2013.1 At several points that summer, five of us writers and curators were each consulting materials on a different floor of Oldenburg’s Broome Street building, effectively rendering it into the equivalent of a giant vertical filing cabinet: one of his monumental sculptures come to life. Several weeks of almost daily visits afforded ample time for lunchtime conversation, initiated by Oldenburg passing around takeaway menus from his favourite local restaurants. Although he carried himself with the elegance of a European diplomat’s son (which he was), he also betrayed his experience as a Fire Island dishwasher, having perfected – like many of us who have washed dishes commercially – his own method for dealing with soiled tableware, barring others from helping with the task. Weeks spent poring over his scrapbooks, journals, nearly forgotten films and documentation of early performances produced enough of a rapport that the generally reserved artist attended a lecture that I gave at Columbia University, New York, on his early sculpture.2 At dinner, I overheard him describe himself as having had two careers: one characterised by the period on which I had spoken, and another dedicated to the large-scale public sculptures initiated in the late 1960s and eventually produced in collaboration with his wife Coosje van Bruggen from the mid-1970s onwards FIG.2.

Art historically, however, one might describe his career as having been divided into at least three periods, for his earliest reception has been marked by a rather stark demarcation arising with the recognition of Pop art as a movement. After debuting his soft sculptures at the Green Gallery in 1962 FIG.3, Oldenburg became known as the pre-eminent Pop sculptor, and since Pop was typically defined as depictions or enlargements of everyday consumer items, his work was primarily discussed in those terms. Stuart Preston set the tone in The Burlington Magazine, recounting: ‘He constructs, out of plaster, paint and sailcloth, gigantic simulacra of pastries, hamburgers, toys, clothes and any number of other familiar objects, all of an appalling fidelity to nature’.3 Prior to that moment, however, writers wrestled openly with the status of Oldenburg’s production, viewing it primarily as painting, not so much hybridised with sculpture as unceremoniously treated as a piece of ductile cloth. Oldenburg himself described it ‘as if I/one had taken the canvas and wrapped it around a ball’.4

Oldenburg’s imagery was often no more straightforward than its form. Many of the pieces associated with the Store did not in fact depict familiar objects, but rather advertisements or, to be more precise, portions of advertisements – as though torn hastily out of a magazine to reveal only a fraction of the goods and prices; see, for example, Red Tights with Fragment 9 FIG.4, Auto Tire with Fragment of Price FIG.5 or Cigarettes in Pack (Fragment) (1961). Oldenburg reproduced such images on plaster-soaked cloth over modelled chicken-wire, which imbued them with a newfound corporeality and which he then covered with the vibrant colours of a lead-based paint that he continued to rhapsodise about, despite its toxicity, five decades later. In this, Oldenburg proved not so much the sculptural equivalent of a Pop painter like Andy Warhol as his opposite. Warhol tended to reproduce the dead commercial object – whether a Campbell’s soup can or the recently deceased celebrity Marilyn Monroe – as a spectral afterimage, high-toned silkscreen colours only serving to dress the corpse. Oldenburg, on the other hand, sought the commodity’s resurrection through the drippy vibrancy of his pigments (which he described as seeming to move of their own accord), the objecthood that he restored via dimensionality, the odd biomorphism of his compositions – consider Cash Register (1961) seeming to move about like a slug – or the actual animation of bodies and objects that took place in his Happening-like Store Days performances of 1962. As he noted of the latter, ‘what cannot be seen as well as what can be seen must be converted into objectivity or inanimateness, which I then (pathetically to be sure) bring “back” to life by my trix’.5

A progenitor of both Oldenburg’s early works of art and his performances may be found in Elephant Mask (1959), a newsprint and wheat paste pachyderm head that he and his then-partner Patty Mucha occasionally wore out in the street. Particularly stimulating for this period of the artist’s production, however, was an interest in fetishism, especially as theorised in the dissident psychoanalyst Wilhelm Stekel’s more-than-seven-hundred-page tome, Sexual Aberrations (1953), which Oldenburg encountered while working at the Cooper Union library. Reading such studies as ‘poetry’ rather than medical science led Oldenburg to imbue his early art and artistic performances with palpably sexual connotations that even his most Pop-centric critics could not fail to note.6

Another facet of Oldenburg’s erotic imagination was spurred by the pioneering queer film-maker Jack Smith, whose East 6th Street apartment he would pass on his way to and from Cooper Union, and for whom he would fabricate an immense pink cake for the film Normal Love (1963–64). The impact of Smith’s still-too-little-known photographs can be discerned in the layers of fabric draped about the languid bodies in the Store Days performances, such as Nekropolis I (1962) or Injun I FIG.6. To my knowledge, only Barbara Rose noted Oldenburg’s relationship to Smith.7 The artist’s interest in the experimental film-maker was significant, however, as he contemplated employing the latter to photograph an ersatz ‘Sex Mag’ set in the Store – an assignment that, in Smith’s hands, would have subverted any straightforwardly heterosexual or commercially exploitative aspects of the pornographic genre.6

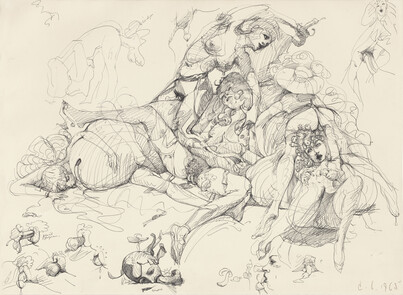

Although the pioneering queer critic Jill Johnston would describe herself as ‘a bit tired’ of the pervasively heterosexual orientation of Oldenburg’s performances, the sexuality evinced by his object world was frequently more ambiguous.9 He persistently combined male and female attributes in suggestive and subversive ways, whether in the detumescent pliability of his soft sculptures or the emasculated militarism of Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks (1969), his first, and one of his most political, monumental sculptures. (This followed an unrealised Colossal Monument to Mayor Daley, which depicted the anti-Leftist Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley’s severed head on a platter. Oldenburg had taken part in protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where he was assaulted by police). One of the most fascinating, albeit almost forgotten, components of Oldenburg’s evolution from Pop art to monumental sculpture consisted of explicit drawings of sexually ambiguous, even ithyphallic, female figures, such as Clinical Study, towards a Heroic-Erotic Monument in the Academic/Comics Style FIG.7. When I brought up these drawings over lunch, Oldenburg explained that he had executed many of them in a single, continuous motion, without lifting pen or pencil from the page: an almost Surrealistic psychic automatism.

All of this is to indicate some of the ways that art history has not yet fully grappled with the complex, ambiguous and subversive nature of Oldenburg’s production, despite his recognition as one the most important artists of his era. This is not, however, solely due to the discipline’s tendency to focus on movements rather than works. It also results from the manner in which Oldenburg himself did not look back so much as forward. Until van Bruggen’s death in 2009, he remained fully committed to their production of public sculpture, the last of which, Paint Torch FIG.8, was installed in Philadelphia in 2011, the year I worked most closely with him. This was why it was such a privilege to spend time with him on the occasion of his retrospective, for it necessitated his reviewing and reflecting upon a great deal of material that he had not seen in decades. Drawings, collages, notebooks, journals, unrealised film projects, slideshows of performances: all were unearthed and examined with fresh eyes. As we inevitably now turn back to examine all eras of Oldenburg’s work with fresh eyes of our own, his past would seem to have a very promising future.

Footnotes

- See B.W. Joseph: ‘Psychological expressionism: Claes Oldenburg’s theater of objects’ in A. Hochdörfer and B. Schröder, eds: exh. cat. Claes Oldenburg: The Sixties, Vienna (Mumok), Cologne (Ludwig Museum), Bilbao (Guggenheim), New York (Museum of Modern Art), Minneapolis (Walker Art Center), 2012–14, pp.72–112. footnote 1

- See B.W. Joseph: ‘Negative capabilities: Claes Oldenburg and Jackson Pollock’, Artforum 51, no.8 (April 2013), pp.230–39 and pp.282–83. footnote 2

- S. Preston: ‘Current and forthcoming exhibitions: New York’, The Burlington Magazine 104 (1962), pp.507–08. footnote 3

- Note in Oldenburg’s archives, c.1960. footnote 4

- C. Oldenburg: Raw Notes, Halifax 1973, p.7. footnote 5

- Note in Oldenburg’s archives, c.1962. footnote 6

- B. Rose: Claes Oldenburg, New York 1970, pp.69 and 184. footnote 7

- Note in Oldenburg’s archives, c.1962. footnote 8

- J. Johnston: ‘Off Off-Broadway: “Happenings at Ray Gun Mfg. Co.”’, Village Voice (26th April 1962), p.10. footnote 9