Paula Rego FIG.1, who died on 8th June 2022 at the age of eighty-seven, was a visionary artist: one who could plunge into the unconscious, pierce the veneer of social acceptability and stare at the cruelty of the world, only to re-emerge having made uncompromising pictures of it all, for us to see and be bewildered by. Crucially, she did so from a position of warm intelligence. Gifted with an unflinching eye and fine-tuned irony, she mastered the representation of psychological and emotionally charged experiences as lodged in and expressed through the body. Always animated, disarmingly humble, warm and with infectious humour, she was ambitious and fearless in her work.

Paula was born on 26th January 1935 in Lisbon and her family provided a cocooned and cosmopolitan, if at times stifling, environment. She loved music and the cinema, and her father, who was an electronics engineer, often took her to the opera. She was surrounded by various illustrated publications at home, fostering her passion for all art forms. From a young age, she began drawing incessantly, sharpening a draughtsmanship of unique clarity that underpinned her work over seven decades. However, her family’s comfortable financial situation could not shield her from the implications of growing up during the dictatorship of the Estado Novo. State and Church colluded to forge a patriarchal regime of stasis and repression in which women’s freedoms were curtailed. Paula’s father, a republican and antifascist, hoped for a different life for his only child. In 1951, at the age of sixteen, Paula travelled to the United Kingdom to attend a finishing school. At seventeen, she enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art, London. How difficult it must have been to be so young, foreign and shy in such an institution. This is where we first detect Paula’s extraordinary inner strength, as she ignored the dominant styles of the time, instead making paintings with a strong social commentary, which looked to Portugal and the condition of women there.

After graduating in 1956, Paula lived primarily in Ericeira until she settled in London in 1963, regularly returning to Portugal. In 1959, she married her first, rapturous love: the painter Victor Willing (1928–88), whom she met soon after arriving at the Slade. They had an intense relationship involving passion, betrayal and reciprocal admiration. Willing recognised the importance of his wife’s work early and, over the years, wrote perceptive and insightful texts about it. Together they had three children: Caroline in 1956, Victoria in 1959 and Nick in 1961.

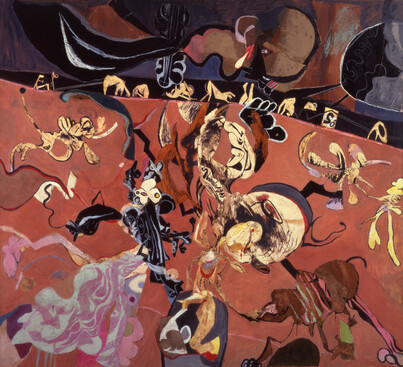

In 1965 Paula began exhibiting with the London Group and showed her work at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, but her work initially garnered significant attention in Portugal. She had her first solo exhibition at the Modern Art Gallery of the National Society of Fine Arts, Lisbon in 1965. Her collage-based works FIG.2 astonished fellow artists who did not dare to address the dictatorship’s brutality in their practice. Paula represented Portugal at the São Paulo Biennial in 1969 and then again in 1974–75. Despite this recognition, it was an extraordinarily trying time for Paula. In 1966 her father died and her husband was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, his health worsening until his death in 1988. This was also when Paula began Jungian psychoanalysis, which she continued for forty years. Jungian therapy, she explained, led her to explore the imaginative origin of the images she carried without knowing their meaning.

It was only in the 1980s that Paula began showing consistently in London. Her paintings of the time revolutionised the representation of women, assigning them agency through their eroticism – in its fullest meaning – as a life force. She had to wait until 1988, when she had a solo exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, London, and secured representation from Marlborough Fine Art, for her work to be fully recognised in the UK. By this time, her female heroines had grown in poise and power. Paula referred to them as ‘heroic handmaidens’: ‘Women have something special to say – a whole fresh view of life – and it’s about time that we heard from them’.1 The writer Marina Warner, after first encountering Paula’s work at the Serpentine, stated that women of the feminist movement had been looking for exceptional figures to emulate. Without a doubt, Paula was such a leading light. In Warner’s words, ‘she gave permission to explore psychic and emotional experiences that had previously been off-limits […] it was a flinging open of the barricades’.2

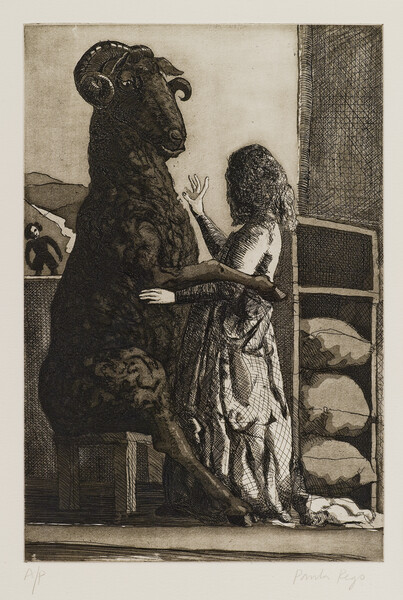

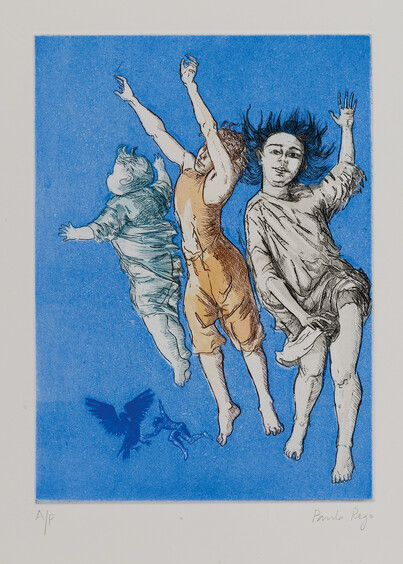

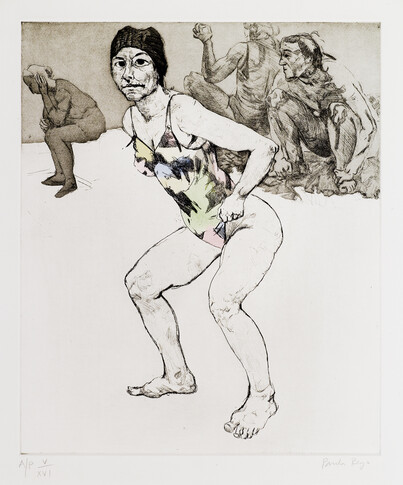

In the late 1980s and 1990s Paula mastered etching, aquatint, watercolour and pastel. Her prints from the series Nursery Rhymes (1989–94) FIG.3, first shown in London in 1989, travelled internationally for years. Many other important series followed, including those dedicated to Peter Pan FIG.4 and the Pendle witches FIG.5. In 1990, she became the first Associate Artist in Residence at the National Gallery, London. Paula had finally achieved recognition and financial stability and moved into the large studio in Kentish Town that she would occupy until her death. From 1994, pastel became a favourite medium, which she used to create some of her most iconic series. The Dog Woman series FIG.6 explored a visceral physicality that veered in all directions: towards rage, abjection, submission and desperate longing. While working on this series, she developed a deep bond with her model Lila Nunes, whom Paula described as a collaborator and who continued to sit for Paula until the artist’s death. The Abortion series (1998–99) FIG.7 was made in response to the failed attempt to legalise abortion in Portugal in 1998. As Paula said, she conceived this work as ‘propaganda’ to deliberately shift opinion. Painfully, the relevancy of the series continues, as the right to abortion is gained or revoked in countries across the world, from Poland to the United States.

From the turn of the century, Paula’s Kentish Town studio was populated with costumes and props as she embarked on the staging of large, dreamy scenes, mixing the ‘dolls’ she made with other props and living models. Blurring the limits of myth, history and personal memories, she built an extraordinary comedie humaine. Paula explored some of the darkest corners of human behaviour but also showed infinite compassion in the depiction of her most vulnerable characters. In 2010, at the Foundling Museum, London, she unveiled Oratorio FIG.8, a large-scale installation that takes the form of an altarpiece cabinet, which explores the horrors of the rape and abuse of children. At seventy-five, Paula was still prepared to go where most artists did not dare, visualising terrors hidden behind closed doors.

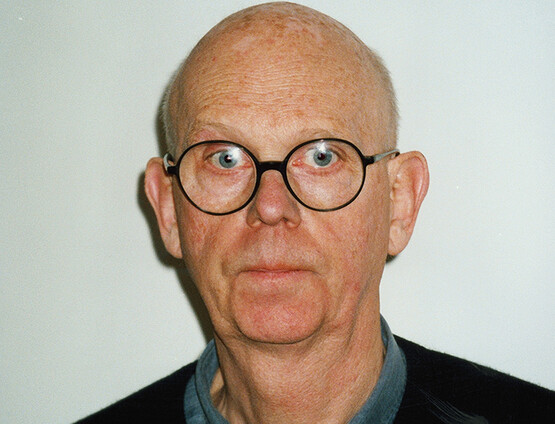

The purpose-built museum Casa das Histórias Paula Rego opened in in Cascais in 2009. Quietly, over the years, the Chief Curator, Catarina Alfaro, and her team have produced some of the most compelling, focused and well-researched exhibitions and publications on Paula’s work. A familiarity with Portuguese culture and history undoubtedly furnishes a deeper connection with her practice, as it centres on an intelligence that is intrinsically connected to the country’s history, culture and spirituality and its continental milieu. Since 1990, Paula’s loyal companion was the writer and translator Anthony Rudolf, who modelled for many of her drawings and pastels. Rudolf’s 2017 collection of poems, European Hours, references many of their shared journeys across Europe, each a pilgrimage to encounter specific artistic expressions.3

From the 1990s onwards, major international retrospective exhibitions were staged, including the comprehensive survey at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, 2007, which travelled to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington.4 Paula’s work gained even more attention following her solo exhibition at the Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, in 2018, and her exhibition in 2021 at Tate Britain, London, which I had the honour of curating, was a lifelong dream.5 The greater visibility afforded by her representation by Victoria Miro, London, and the inclusion of a monographic room dedicated to her work in the 59th Venice Biennale fostered a new degree of recognition as Paula’s health deteriorated. Following her death, while the significance of her work will continue to grow internationally, it is in Portugal that she is considered a national treasure and was given a state funeral.

Paula was an extraordinary woman who managed to navigate life through many troubles and imbue all that she felt, deeply, into her work. Depression, as she revealed late in life, caused her extreme pain over many periods. The documentary Paula Rego, Secrets & Stories (2017), directed by her son Nick, provides a unique insight into her life and work. Uncompromising, incredibly moving and yet full of humour, it is a beautiful and intimate portrait of a mother by a devoted son. Paula famously said that she painted ‘to give fear a face’.6 In her work, she confronted our collective fears. She represented bodies that are free, inasmuch as they express the lived experience fearlessly – no holding back, no feigning, no shame. This is perhaps Paula’s most extraordinary gift: she depicted human experience without judgement and with radical honesty, beyond the field of consciousness.