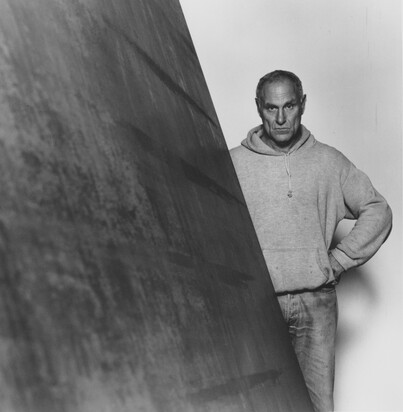

The sculpture of Richard Serra FIG.1, who died on 26th March at the age of eighty-five, is physically and materially imposing, intellectually complex and subtle, and yet he often said it could be fully appreciated by any child who could walk around or along its elements. His work is concerned with place, determining the scale and physical conditions of the space it occupied, and many of his sculptures were planned as site-specific, so that they should not, or could not, be moved.

Serra was born in San Francisco, where his father worked in the shipyards, and he always maintained that seeing a steel hull launched into the water from the dock was a formative experience for him as a small child. He studied literature at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and then painting at Yale, New Haven. In 1965 he received a travel scholarship to study in Paris, where he often visited the Atelier Brancusi and frequented La Coupole, hoping to find himself in the presence of Alberto Giacometti (1901–66), a lifelong hero. He travelled widely, had his first exhibition in Rome in 1966 and returned to work in New York, where his peers were such artists as Robert Smithson (1938–73), Brice Marden (1938–2023) and Joan Jonas (b.1936), the dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer (b.1934) and the composers Philip Glass (b.1937) and Steve Reich (b.1936). In the 1970s he worked extensively in Europe, especially in Germany, where he could make large-scale works in the Ruhr steel mills.

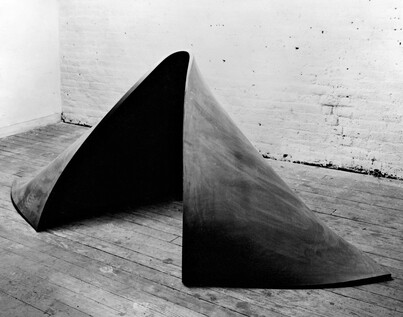

Serra’s death concluded an exceptionally consistent and coherent artistic career, which was definitive of its period for more than half a century. The early work To Lift FIG.2, now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), contains within it almost all of his preoccupations – weight, density, line, plane, interior and exterior volumes – which would find their apotheosis in his Torqued Ellipse series from the 1990s onwards. His work is primarily made out of steel, although he also made sculptures in lead, stone, concrete, rubber and neon, and his drawings and prints – often made using oil-based paintstick and other materials – never deviate from a dense black colour. His final work, in 2022, is also his largest single forged round: a cylindrical steel block weighing over 70 tonnes.

I first met Serra in 1977 at documenta 6 in Kassel, at a time when his work had hardly been seen in London; later, I was privileged to work with him on a number of occasions. In 1991 I co-curated, with Lynne Cooke, the Carnegie International, for which we asked Serra to install an enormous two-part drawing on canvas in one of the galleries in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. In the mid-1980s Serra had been particularly appreciative of the museum’s support in commissioning a sculpture for their Fountain Plaza when the Tilted Arc (1981) controversy was ongoing in New York, especially given the tradition of steel production in Pittsburgh.1 In 1999 I wrote about his work when it was first installed at the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao. Since then it has evolved into The Matter of Time FIG.3, a permanent installation that has become an essential destination for aficionados of Serra’s work.

At this time his reputation was transformed, and the Torqued Ellipses in particular became unexpectedly popular. He received many commissions for public sculptures and staged major retrospectives in museums worldwide, and found himself in a position to explore the technical and physical limits of his materials. Serra was extremely articulate about his work and its place in the history of art, collaborating in long interviews with David Sylvester and then with Hal Foster, his closest interlocutor – other than his wife, Clara – which have been collected into a compelling book titled Conversations about Sculpture (2018). In these conversations, Serra acknowledged his unique historical status, between the Industrial Revolution and post-industrial technologies, when he remarked: ‘I don’t think anybody will follow what I’ve laid out’.2

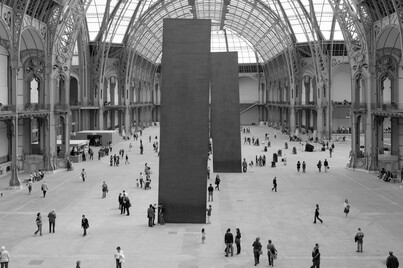

In 2008 Serra installed Promenade FIG.4 at the Grand Palais, Paris, a public project that took two years of preparation and planning. Comprising five enormous vertical steel plates subtly aligned on barely visible angles along the axis of the great hall, the work was a precursor to East-West/West-East FIG.5, sited in the desert landscape in Qatar. At the same time I was able to persuade the City of Paris to reinstall Clara-Clara (1983) in the Tuileries Gardens temporarily. The city acquired the work in the 1990s but still has not placed it in a permanent site – an issue that has now taken on a renewed urgency.

I remember a short visit to St Petersburg in 2017, while en route to an exhibition of Serra’s recent drawings at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. At the State Hermitage Museum, Serra was able to see a version of The Black Square (c.1932) by Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) – a foundational touchstone for the origins of abstract modern art – but he was also evidently delighted to encounter the great early Henri Matisse (1869–1954) paintings. In the last two decades, Serra had significant museum exhibitions, including Brancusi-Serra, which paired his work with that of Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957); a second retrospective at MoMA; and Serra/Seurat. Drawings, which surveyed his drawings alongside those of Georges Seurat (1859–91), the artist’s favourite historical master of monochrome.3

Serra’s work is indivisibly connected to these early modernist masters and refreshes this tradition in its adherence to lived and felt experience. Some years ago, the critic Rosalind Krauss, an old friend of Serra’s, celebrated his work with the following tribute:

Looking across the tops of Nine Rounds I saw a series of circles moving away from me, as though I was viewing the waves of a sea. The visual impact along with bodily force of the weight of the elements brought to mind the opening of Joyce’s Ulysses where he marries vision to bodily experience, when he begins: ‘Ineluctable modality of the visible, thought before my eyes’. Stephen Dedalus is staring out to the horizon of the sea while looking at the sand below his feet and his meditation is bodily, his transport married to his weight. Richard, you have captured this valuable feeling and for that we thank you.4

Serra’s work will long endure, not only in the great collections of his work in Qatar, Iceland, New Zealand, Bilbao, New York and other locations, but because he investigated the fundamentals of his medium, and found new and unprecedented ways to make sculpture live in the world FIG.6.

Footnotes

- Tilted Arc (1981) was a public art installation commissioned by the General Services Administration for Foley Federal Plaza, New York. After it was installed it elicited a strong negative response, mostly from office workers in the nearby area who felt that it had a profoundly negative impact on their experience of the space. Despite it being a site-specific work of art, petitions were created to remove it and a public hearing was arranged to discuss its relocation; the panel voted in favour of doing so. It was removed in March 1989 and has not been exhibited since as requested by Serra. See J. Mundy: ‘Lost art: Richard Serra’, Tate, available at www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/richard-serra-1923/lost-art-richard-serra, accessed 13th May 2024. footnote 1

- Richard Serra, quoted from R. Serra and H. Foster: ‘Symbolic forms’, in idem: Conversations about Sculpture, New Haven 2018, pp.151–71, at p.168. footnote 2

- O. Wick, ed.: exh. cat. Brancusi–Serra, Riehen (Fondation Beyeler) and Bilbao (Guggenheim) 2011–12; K. McShine and L. Cooke: exh. cat. Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years, New York (Museum of Modern Art) 2007; and L. Agirre: exh. cat. Serra/Seurat. Dibujos, Bilbao (Guggenheim) 2022. footnote 3

- Rosalind Krauss, quoted from a talk at a dinner in celebration of Richard Serra, 2017. footnote 4