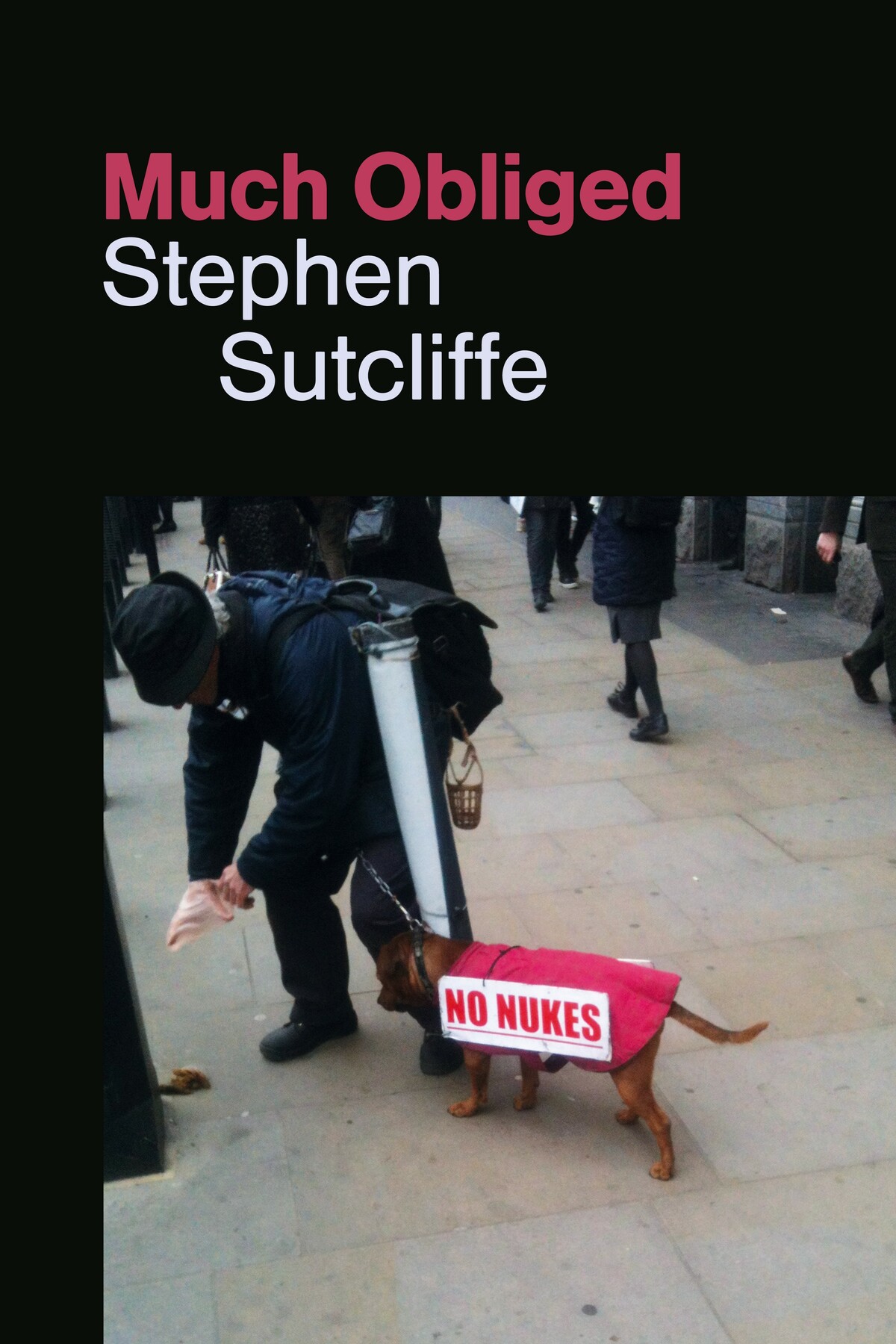

Last year the artist Stephen Sutcliffe published two books. Much Obliged takes the form of an autobiography composed entirely of anecdotes, an assemblage of extremely funny vignettes recounted by a third-person ‘Stephen’. Stephen Sutcliffe: at Fifty functions as something close to a catalogue raisonné or monograph (the artist’s first). An attempt to encapsulate two decade’s worth of work into a coherent whole, it gives an in-depth sense of Sutcliffe’s thematic preoccupations and visual style. Likewise, any reader of Much Obliged will feel they have had more than a glimpse into the artist’s Yorkshire childhood and adolescence, a life lived through stories shared. But the real success of both books is that they go far beyond what is required (and usually produced), exceeding and disrupting the conventions and expectations of the autobiography and art catalogue respectively.

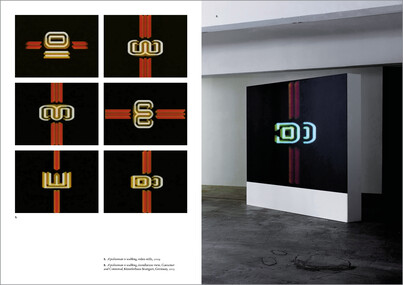

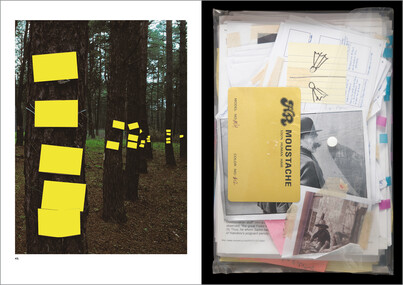

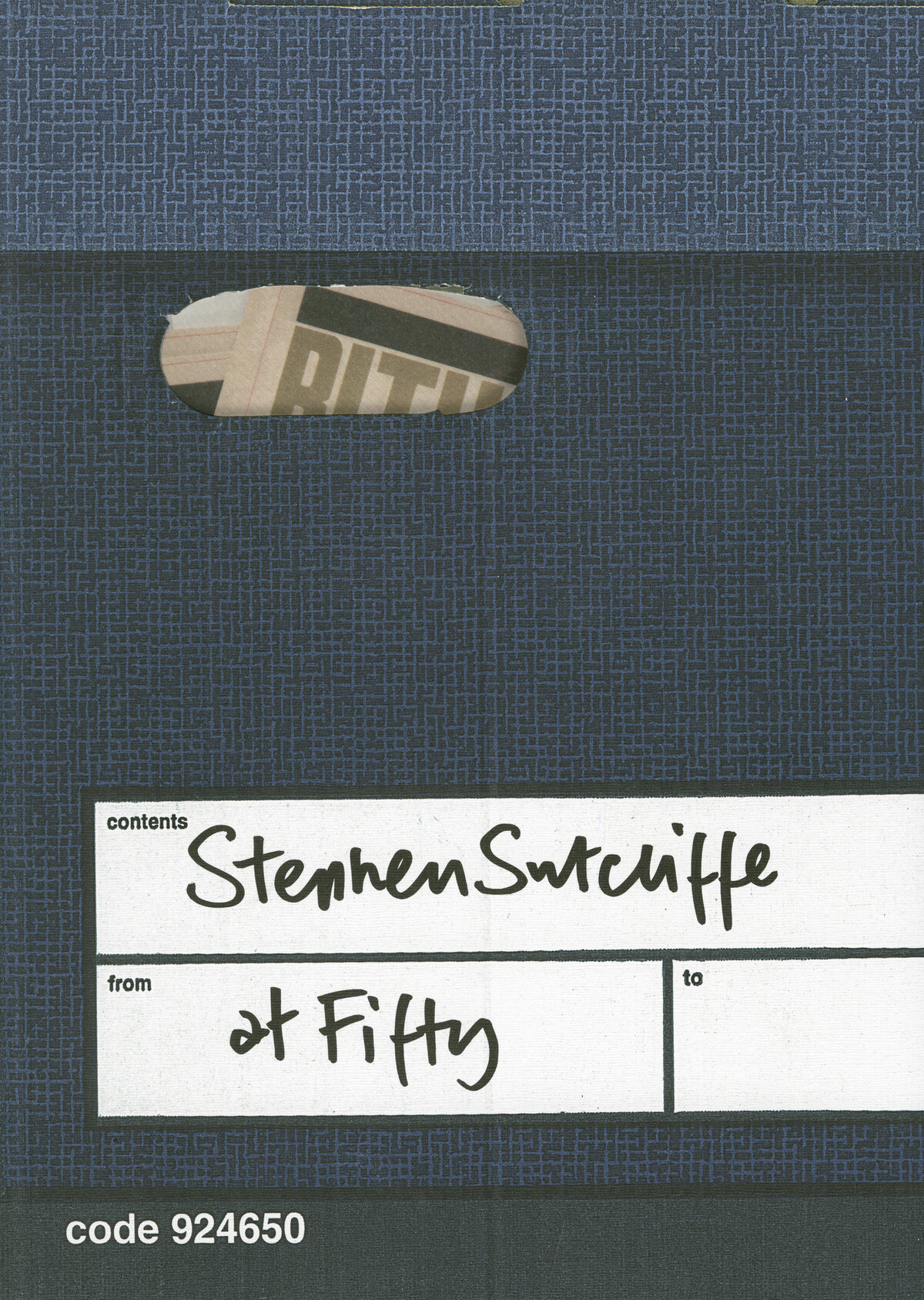

The significance of at Fifty as an example of art publishing lies in its refusal to conform to the standard monographic form, almost always encountered as the curiously unimaginative formula of essays + plates + CV. Although at Fifty includes these elements, it functions as much as a standalone work of art as a monograph or extended exhibition catalogue. The book’s design makes this apparent from the outset, formally embodying some of the characteristics of Sutcliffe’s art and, through this, immediately contesting the false dichotomy between form and content. The varying weight and texture of the paper throughout the book, for example, suggest that this is an object to be handled, appreciated for its tactility and materiality as well as its ostensible ‘content’. The inside back cover tells us that ‘the different paper stocks used in this book’ have been ‘selected from surplus stock that the printer has used for recent publications. This fits with the book’s overall spirit of collage and suits an artist who has an aversion to choice and likes to work with what’s “left”’. Fittingly, then, for an artist whose work has so often been based on his own personal archive and the archives of others (such as Lindsay Anderson and Herbert Read) the wraparound cover looks like an archive box, labelled ‘Contents: Stephen Sutcliffe / From: at Fifty’. The material inside is similarly archival, including images of the artist’s exhibited works (mainly film stills) as well as pictures of an array of the source material that informs his work – VHS tapes, paperbacks, newspaper cuttings, exhibition invitations and other personal ephemera – amassed since childhood. Folders, sketches, jottings and post-it notes are also included, providing an insight into Sutcliffe’s working methods.

Even the essays go further than usual, imbuing the book with a self-referential, looping quality as though they too attempt to embody aspects of the artist’s work while at the same time explicitly discussing those aspects. Michelle Cotton’s interview with the artist, for example, opens:

Michelle Cotton: I like interviews, they are often the first texts that I read when I’m researching artists, but I thought it was funny we’d decided to do this after I’d watched all your films again and was reminded that interviews were a running theme in your work. There are a lot of uncomfortable scenarios in your videos and I began to wonder if you were setting us up for a catastrophic failure.

Stephen Sutcliffe: Yes, there’s always that danger with interviews, it’s like a conversation but it’s not a natural situation.

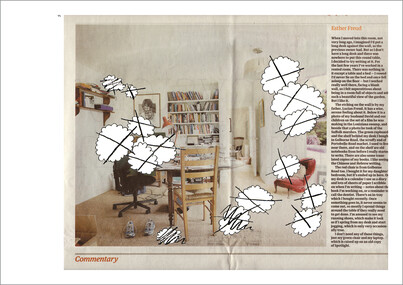

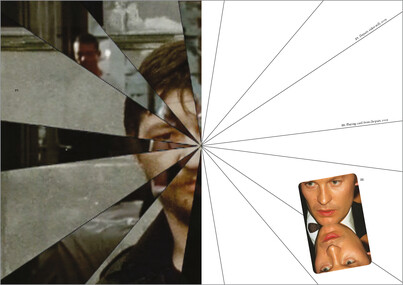

The two go on to discuss interviews as a form, self-doubt, how public figures represent themselves (and how this fails), autobiography, portraiture, class consciousness and a range of other features and themes for which Sutcliffe’s work is known. Almost all of these points of discussion are reflected in the interview itself. Sutcliffe notes that what he does ‘as a person as well as an artist is basically collage’, citing the biggest historical influence on his work as the library book collages of Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell. In turn, Ilsa Colsell, author of an in-depth history and annotated collection of the books systematically ‘defaced’ by Orton and Halliwell,1 adopts a fragmentary, collage-like structure for her essay on Sutcliffe’s use of collage, wherein her interpretative, explicatory essay is interspersed, overlaid and disrupted by close readings of individual film or video works stopped at a particular point. We break from the main body of the text to read a dense description of the action at 07.54 in Despair (2009), an account of what we see at 08.47 in Outwork (2013), or at 01.22 in Come to the Edge (2003). It is an effective strategy, combining detailed and specific visual analysis with broader contextual discussion.

Dan Fox also mirrors the content of Sutcliffe’s work by responding autobiographically to the overarching source material and subject matter of Sutcliffe’s work: autobiography and post-war British television. ‘Try as I might to climb to a higher altitude of critical distance from Sutcliffe’s films’, Fox writes, ‘to appreciate their clinical, deconstructive potency from a safe remove, I repeatedly come crashing back down into a subjective proximity to his work, which is apt.’ Same here, and I suspect the same would be true of many readers of this book, especially those over forty who grew up in the United Kingdom. In reading Sutcliffe’s comments on class identity, accent and northern-ness (in the interview with Cotton) I was reminded of my own class confusion, my teenage aspiration signified by the purchase, c.1990, of a faux leather cover for the Radio Times. I still have it, and regard it with an equal measure of embarrassment and pride. at Fifty is a remarkable accomplishment. It is unusually forthcoming about how art is made (and would therefore be highly recommended for any student seeking to understand what ‘practice’ really means), it is a comprehensive survey of a twenty-year career and, through its physical form, demonstrates the artist’s punctilious approach to any project.

In its own way, Much Obliged tells us as much about the artist as at Fifty, though from a very different vantage point. A few pages in, for instance, the artist’s formative years are recalled in a passage that sets the tone for the book: ‘In Dewsbury Stephen took two drawings to his interview for Batley School of Art. One of was of Jeff Bridges running away from a burning plane holding a baby’. Along with a central section of photographs and drawings (as funny as the prose and sometimes illustrative of certain anecdotes) Much Obliged is entirely composed of these droll reminiscences, one or two per page, revealing sometimes intimate and darkly comic details about family dynamics, art world disappointments, horrible jobs and school yard humiliations. It also mercilessly documents the faux pas, non sequiturs and spoonerisms of family and friends.

The introduction, by Benjamin Cook, tells us that both Cook and Sutcliffe are admirers of the American artist Joe Brainard, whose 1970 memoir I Remember informed the style and structure of this book, Sutcliffe’s own ‘minor key autobiography’ told through a series of micro-stories. Much Obliged also recalls other ‘alternative’ forms of memoir or collected anecdote. Craig Brown’s 2017 Ma’am Darling: 99 Glimpses of Princess Margaret, for example, is an enticingly waspish portrait of the monstrous Margaret often told through reports of her withering put-downs. John Waters’s 1986 Crackpot: The Obsessions of John Waters relies heavily on recorded speech and anecdote, as though Waters himself is made up of the influences and role models who speak both through and for him. But Much Obliged is perhaps closer in spirit to Kenneth Williams’s Acid Drops, written in 1980 when Williams ‘only realised the value of a diary when I stopped using it just for recording appointments and put down some of the dialogue I remembered’. Like many of Sutcliffe’s works, the pages of Much Obliged focus on episodes not intended to be historicised: interruptions, awkward encounters, gaffes and cutting remarks. As Cook notes, Sutcliffe’s sardonic self-deprecation chimes with John Ashbery’s assessment of John Brainard’s work: ‘humane smut’. We find out on the final page that the book’s title is taken from Stephen’s father’s way of saying thanks. As a conclusion it makes for a bashful thanks to the reader for their indulgence, but it is the incongruity, hyper-specificity and apparent sincerity of many of these anecdotes that makes them so comedic and rewarding. For all their caustic wit, these recollections are also extremely warm, affectionate and familiar portraits of family and friends.

The tonal contrast between the two books allows them to work particularly effectively as companion pieces. Whereas at Fifty has gravitas in scale and scope, acting as an important, if overdue, record of the development of an exceptional practice, Much Obliged almost thumbs its nose in response. It is a smaller book, composed of one or two autobiographical fragments per page. It’s a good laugh, a bit of fun. It could be read and enjoyed by anyone, and is not contingent upon any knowledge of the art world in general or the artist or his work in particular. But as good as it is as a joke book, read in tandem with at Fifty, Much Obliged provides context, colour and specificity to Sutcliffe’s more reflexive and critical references to class, the art world and fitting in. It shows rather than tells of the auto-didacticism fostered and facilitated by the television in the 1970s and 80s (see Stephen’s intellectual one-upmanship on page 29) and both books emphasise the artist’s love and use of anecdote, both from his own life and the lives of his subjects and characters. In Much Obliged, Stephen (author and narrator) tells us that ‘any carryings on would be met by Stephen’s dad with a simple, “We’ll have less”’ We are then informed that ‘this would be the title if Stephen wrote another book.’ On the basis of these two publications, I hope he does.

Footnotes

- I. Colsell: Malicious Damage: The Defaced Library Books of Kenneth Halliwell and Joe Orton, London 2013. footnote 1