Simeon Barclay: England’s Lost Camelot

by Alex Hull

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 29.09.2021

Camelot – the magical realm of King Arthur, where enchanting wizards, damsels in distress and noble knights lived together – has grasped the imaginations of children, adults, artists and authors for centuries. The narrative of Arthur is a construction of medieval history, folklore and literary invention. The Tudors claimed him as an ancestor – a great British military leader who validated Britain’s ‘divine’ right to conquer land; and in the nineteenth-century his legend captivated audiences as it was reinterpreted within the burgeoning Romantic literary tradition.1 Chivalrous and valiant defenders of the nation, Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table espouse a particular form of masculinity that has come to epitomise the British gentleman. For his solo exhibition England’s Lost Camelot at Workplace, London, the artist Simeon Barclay (b.1975) takes the legacy of the gallant knight as his starting point, using it to explore the many masks and myths of masculinity and nationhood, and to underline the dominant ideas inherited from folklore that still govern national cultural hegemony. Elements of the artist’s personal archive and pop culture references are pulled together to create a rich retelling of British identity that examines themes of inheritance, hierarchy and exclusion through the lens of race, class and gender.

Barclay has transformed the opening corridor using blue lighting, red roses littered on a black floor and an intensifying electronic beat that echoes throughout. The installation, coupled with the intonations of the soundtrack, elicits an anticipation similar to that felt before stepping into a nightclub: a cocktail of nerves and excitement. For Barclay, the club has always been a site of cultural education; it became his night school, which he attended after he clocked off from his factory job in Yorkshire. Whereas at work he was expected to perform a rigid idea of masculinity, clubbing afforded him the opportunity to explore gender expressions outside of conservative societal expectations. At the other end of the corridor sits an old television set, which plays Slow Dance with Mirror (2021), a looped video of silent black-and-white clips of the iconic World Champion snooker player Alex ‘Hurricane’ Higgins as he paces around the table FIG.1. As a young boy growing up in the 1980s, Barclay vividly remembers watching Higgins playing on TV and crumbling in front of the nation during a match – a fall from grace that shattered his conception of Higgins’s masculinity.2 Higgins was a notoriously heavy drinker and smoker with a volatile temperament; he got into fights at matches, which resulted in the downfall of his career.

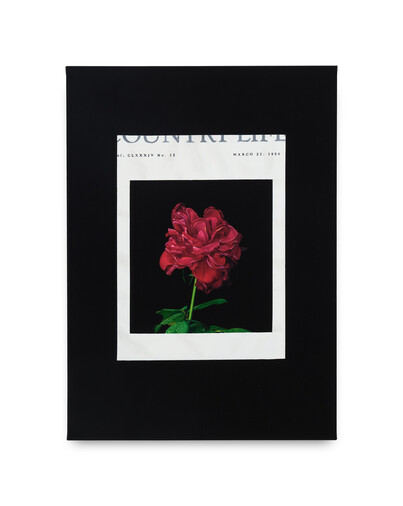

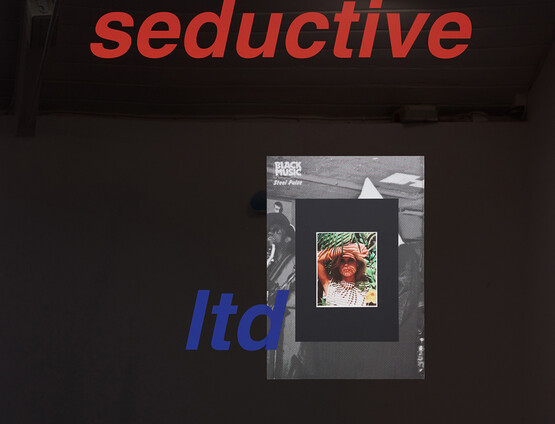

The red roses function as a control mechanism within the space, guiding the viewer into the main room where more are scattered FIG.2. The English rose signifies a uniquely British idea of beauty, one that champions a specific vision of race, class and gender: a white, upper-class woman who conforms to traditional ideas of femininity. The roses simultaneously serve as a memento mori, their inevitable death highlighting the cycle of life. Their positioning across the gallery floor forces the viewer to move self-consciously, so as not to stomp over the floral installation. The iconography of the rose reappears in two other works: as an intricate painting of a cropped Country Life cover in Miss Jennifer FIG.3 and woven onto a rug with a printed image of two lovers, brocaded with a blue floral pattern in Hear Between the Silence FIG.4.

Another physical obstruction for the viewer in the exhibition is Bird Cage FIG.5. A pair of distressed helmets coated in black powder hang in the centre of the space at the artist’s head height. In conjunction with the magnified negative illustration of a knight that covers a gallery wall, the helmets are a direct reference to the exhibition’s starting point. Symbolic of battle, the armour has been kinked and bashed in. These objects – like their historic counterparts – also function as masks: concealers of identity and state of mind in order to psychologically protect the wearer and convey an emotional stoicism, the notorious British stiff upper lip. As bell hooks writes: ‘There is only one emotion that patriarchy values when expressed by men; that emotion is anger. Real men get mad. And their mad-ness, no matter how violent or violating, is deemed natural – a positive expression of patriarchal masculinity. Anger is the best hiding place for anybody seeking to conceal pain or anguish of spirit’.3

A Mystic voyage (A Pantheon of Omissions) for an Imaginary Drinking Hole – a title that pays homage to Roy Ayers’s 1975 jazz album Mystic Voyage – encapsulates a fantasy of Barclay’s as he imagines his own pub, ‘THE MONOLITH ARMS’. The work of art mimics a traditional pub sign; its metal bracket – a nod to industrial fabrication processes – hangs from the ceiling and lights illuminate the green board. The Black Liberation flag and an old flag of Ethiopia, which is commonly used in the Rastafarian movement, border a painted scene of twelve significant figures of Black political resistance, including Martin Luther King Jr, Elijah Muhammad and Bob Marley. Barclay gathers them together around a table laden with fruit and wine in a recreation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper; they are all dressed in similar attire, marking them as part of a club. The tavern’s title is indicative of the group as unified and powerful and references the literal and metaphorical armour that forms part of the exhibition, while also nodding to conventional pub names that commonly reference heraldry. ‘FREEHOUSE’ at the bottom incorporates a Black Power fist as a replacement for the letter ‘o’, indicating that it is an independently owned pub, not controlled by the breweries that supply it, giving autonomy to its occupants.

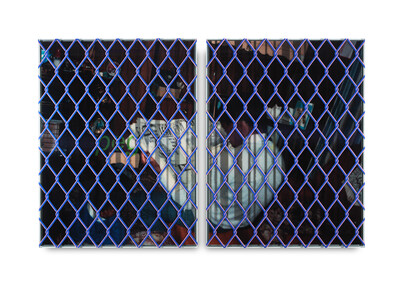

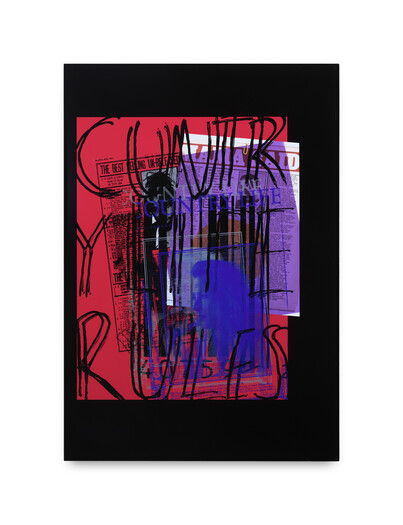

Other works of art in the show include I am down FIG.6, a photographic diptych of Barclay as a young child reading a newspaper. It is overlaid with a wire fence and a Lenticular printing process causes an optical effect so that the words ‘peg’ and ‘drift’ are revealed or concealed dependent on where the viewer stands. A similar theme of exclusion is also explored in Chips on My Shoulders (2021) and Clan In Da Front FIG.7, which layer cuttings from comic books, magazines and newspapers with scrawled words and barcodes. In the former, a cartoon drawing of two young girls is mirrored, the text in their speech bubbles printed in reverse: ‘We’re at boarding school because our parents work abroad’. Such fee-paying schools, reserved for the upper middle class, give their students significantly greater professional, academic and economic advantages, despite the fact that they constitute only six per cent of the United Kingdom’s school population.4 In contrast, Barclay attended state school until the age of sixteen: ‘Perhaps because of my class, I had a bit of a chip on my shoulder’.5 This work takes its title from the song ‘Chips on My Shoulder’ (1981) by the Leeds-born duo Soft Cell and Clan in Da Front is titled after a 1993 song by Wu-Tang Clan. In these collage works, Barclay creates a visual language that is not immediately accessible – and in parts, so obscured that it is illegible – necessarily complicating the viewer’s relationship with what is presented.

Both playful and controlled in its environment, England’s Lost Camelot is a generous exploration into Barclay’s identity as a Black, working-class artist who has often worn many masks to both present and protect himself. In this body of work, he examines the ways in which ideas and mythologies of masculinity, Blackness and Britishness intersect. Despite the use of his personal archive and pop cultural references that are significant to him, Barclay refuses nostalgia, instead drawing on a wide range of sources to map and challenge stereotypes that are perpetuated through colonialist and capitalist frameworks.