Blockchain manifestos: fighting for the imagination of a culture

by Charlotte Kent • Journal article

by Charlotte Kent

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 28.07.2021

In the midst of the recent hype around blockchain and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), TRANSFER Gallery, Los Angeles, and left gallery have collaborated on Pieces of Me, an online exhibition of work by fifty artists who engage with the various complexities associated with this technology. Digital art is a variable term, reflecting its lineages in computer art, new media and internet culture, as well as conceptual art, abstraction and the expanded field of sculpture. Art that engages with blockchain presents a chance to learn lessons from these distinct practices: the marginalisation of certain communities and aesthetics; the limiting of perspectives caused by corporatisation and financialisation; territorial fiefdoms undermining creative cross-pollination; and obscure technology and art speak that alienates audiences. Pieces of Me is a conceptually rigorous exhibition that examines the power, potential and problems within the worlds of art and technology.

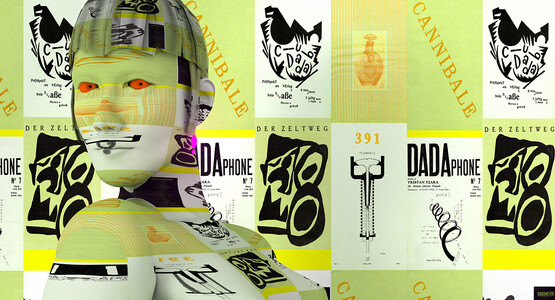

The fifty works included are loosely arranged into eight thematic rooms, which are given titles based on Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993), a science fiction novel set in the 2020s. The exhibition brings together artists who have had ‘traditional art market success’, such as Claudia Hart, Zach Blas and Lawrence Lek FIG.1, those who have recently enjoyed ‘NFT market success’ – Travess Smalley, Serwah Attafuah FIG.2 and Sara Ludy – and those classed as ‘skeptics and critical thinkers who are pushing the conversation forward’, such as Cassie McQuater FIG.3, Alice Yuan Zhang and Ryan Kuo FIG.4.1 What ties their efforts together is not style or medium, but a conceptual engagement with NFTs, which guarantee the singularity of digital assets, and the blockchain, where these receipts or certificates are stored.

For Wade Wallerstein, one of the exhibition curators, a major issue with blockchain is how to transact with intention. For Pieces of Me, each artist determined their own sales contract, disrupting the disenfranchisement that artists often experience in the sale of their work, both online and offline. Standardised sales practices – similar to those in commercial galleries and auction houses, such as established percentage allocations of artist sales – have been applied to blockchain platforms, despite the technology allowing for possible, and simple, customisation. As Wallerstein says, ‘there is no need to rush into this marketplace, or to follow protocols that do not suit or feel extractive or hyper accelerated. There is not one way to organize and sell, but rather many ways that can coexist with or diverge from the norm’.2 Recognising the distributed ethos of blockchain, any works sold in this show profit all the exhibitors: artists receive seventy per cent of their own sales, while the remaining thirty per cent is distributed amongst the pool of remaining artists and knowledge workers, technologists and gallerists who were involved in the exhibition’s creation.

The room structure presents a kind of order to the breadth of the show, which audiences can roam at will. Each work of art has its own webpage, including artist information, a brief text and the terms of sale; collectively these materials substantiate the exhibition’s overall inquiry into how blockchain can both illuminate and occlude issues in the relationship between art and technology. Approaches of the exhibited artists range from the take-the-money-and-run attitude of ‘Don’t Look Back, Don’t Look Down’ to the aspirational nature of ‘Close Your Eyes, Make a Wish’. Throughout the exhibition, the question remains: how do art and technology define us and the worlds that we create?

The first set of works, organised under the title ‘This is Who I Am’, concern how art and its commerce relate to identity. McQuatar’s moretoMe.txt rejects the form of exchange that is inherent in blockchain by offering a work that is not for sale. For their work Nā ka’e o ka manawa (The edges of time) FIG.5, the artists Tiare Ribeaux and Jody Stillwater have produced a composite panorama of lava rocks on the Wailuku River on the Island of Hawai‘i. A third of their sale will go to the Aloha ‘Āina Support Fund, which protects the Mauna Kea volcano from industrial development. LaJuné McMillian’s Self Portrait FIG.6, an animated GIF based on a three-dimensional scan of the artist’s head, is a part of her Black Movement Project, an online database of motion capture data from Black performers. A tool for activists, performers and artists to create diverse extended reality (XR) projects, the project is a response to the current under-representation of Black bodies in available databases.

The second room, ‘Don’t Look Back, Don’t Look Down’, presents cautionary tales from artists who are familiar with past enthusiasms around technologies and ideologies. Danielle Brathwhaite-Shirley’s TERMS AND CONDITIONS FIG.7 is a fierce indictment of easy allyship. The animated GIF demands active support of the Black Trans community, and purchase of the work requires agreement to the terms and conditions it sets out: the buyer must display a print of the work in ‘their physical space for a period of two years’. While the work asks ‘the collector to value, uphold, and wear proudly a badge of real allyship’, it also discourages the potential to flip – to purchase the work for quick resale. However, Brathwhaite-Shirley knows that the blockchain cannot enforce this contract, and so the work becomes a subversive demonstration of why artist-collector and artist-patron relations remain crucial to art’s meaningful impact.3 Although Faith Holland’s boobs.gif may seem to cater to ‘tech bro’ mentality, the relentless jiggling of multiple, anonymous pairs of breasts ridicules the notion of the internet as any kind of idealist community, instead highlighting its role as a global pornography distribution centre and a space of increasingly aggressive harassment.4

‘I Don’t Belong Here/This is Where I Belong’ presents artists who navigate the liminal space of digital art, working between media, communities and different outlets. Kumbirai Makumbe’s The Gate exemplifies an overall concern with media specificity and materialism, which results in a work that crosses the binary division of the virtual and the tangible. Makumbe’s offering includes a silver-glazed ceramic 3D printed sculpture FIG.8 with its digital model FIG.9. Uniting these two realms is in keeping with the artist’s efforts to explore ‘alternative modes of being and thinking that could negate exclusionary acts and ideologies’. ‘We’ve Been Waiting for You’ features artists who are experiencing a renewed interest in their work now that the value of NFTs has validated the digital space. Previously, due to a scepticism of the creative standing of the computer arts, these artists – such as Molly Soda and Maria Olson – were deemed insufficiently formal; some deviated from the abilities of the machine to focus on social politics, while others incorporated tools and references from social media or video games into their intersectional creations. NFTs have complicated these categorical distinctions and media hierarchies – challenges that are not dissimilar to those that Pop art bought to the fore in the 1960s.

Pop art did not innovate merely by referencing advertising and mass media, as earlier art movements had already done. Instead, artists invoked the commercial world in their work to raise questions around media and genre hierarchy, the gentrification and standardisation of Modernism, and supervening (super)market aesthetics. Pop art was a critique of modernist elitism and a rebuttal to abstraction’s ideological superiority, but a reappropriation of its methods can become mere banal simulation. For example, the act of collaging elements from our digital terrain, as Beeple did for Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021), does not make the work synonymous with Pop art.5 Contemporary works of art that incorporate popular imagery are consistently framed in this lineage, the legitimacy of which the present reviewer frequently doubts. When digital art cites memes or social media influencers, it is difficult to raise the work out of redundancy. Today, reiterating the market tendencies of data capitalism and the algorithmic junk food of our daily lives rarely works as a critique. We are too deeply steeped in the game show aesthetics of infotainment and ironic pastiche – the cool detachment of capitalism itself – for these attitudes to be convincingly critical.6

Blockchain, like so much else, defines exchange through capital, but what if it were otherwise? The room ‘Close Your Eyes, Make a Wish’ presents works that imagine alternate structures, such as the collective Keiken’s web-based video game, Wisdoms for Love 3.0 (Metaverse: We Are At The End Of Something) FIG.10. The collaborative posits an entire metaverse in which wisdom tokens enable players to get to Love 3.0, as opposed to the Web 3.0 that blockchain is supposed to herald, whereby the internet will be available to everyone, everywhere, all the time, through smart devices that connect us all in a vast realm of perpetual data connectivity. Perhaps that is not everyone’s vision of utopia. ‘Take a Picture it’ll Last Longer’ imagines the extravagances that imbue the realm of representation; notably, Web 3.0 is supposed to blur the virtual and physical worlds.7 Julieta Gil’s Patriarchal Sculpture Park FIG.11 comprises a series of 3D scans of sculptures from around Mexico City that ‘represent patriarchal constructs’. The scans are offered as 3D model pack, a nod to crypto collectibles but one that undermines their usual uncritical memorialising.

The significance of the show is most apparent in the final selection, ‘You Can’t See the Future with Tears in Your Eyes’. Decrying blockchain – its financialisation of relations, reiteration of platform mentality and overhyped opportunities – prevents us from engaging with the technology itself. The model presented by auction houses or NFT platforms is only one way to operate on the ledger. Pieces of Me resists the ‘aggregate hype of the global NFT marketplace’. In its more considered approach, it manifests as a commentary on the position of pop culture and, by extension, Pop art. The institutionalisation of the visual culture surrounding NFTs imitates the cultural appropriation of Pop Art as a brightly hued but shallow indictment of capitalism. However, the institutional embrace of both has similarly stripped them of their subversive and politically creative potential. It is easy to forget that Pop art initially critiqued art world attitudes and practices, which blockchain and therefore NFTs can also do, however standardisation and institutionalisation is quickly impeding any such possibility within this emergent technology. That a web-based exhibition solely about blockchain should manage to invoke such issues is impressive. In Pieces of Me, the curators, Wallerstein, Kelani Nichole and Harm van den Dorpel, reject the uniform position that blockchain has assumed, and insist on a critical stance that examines how it operates across the cultural stratosphere. They showcase works that deviate in style, content and medium in order to pointedly argue that blockchain’s potential is far more diverse than many current platforms would have us realise. At the same time, they also recognise its redundancy: much of what it can do is already possible in paper form, by the bonds and ethics of care that go into being true patrons of the arts.

This is not just a digital exhibition about technology, but also a portrait of how society is frequently shaped by abstract proposals, misrepresentations and unquestioned ideologies. The show insists that blockchain will only become monolithic if artists ignore the variety available to them; if collectors refuse to discover and diversify; and if audiences are misled by media hype that marginalises the politics of blockchain’s conceptual landscape. New technologies are not simply a trajectory forward, but also a chance to reflect on what we have designed thus far. As such, this exhibition represents the real politics of Pop art for our time.