Blockchain manifestos: fighting for the imagination of a culture

by Charlotte Kent • Journal article

by Charlotte Kent

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 26.01.2022

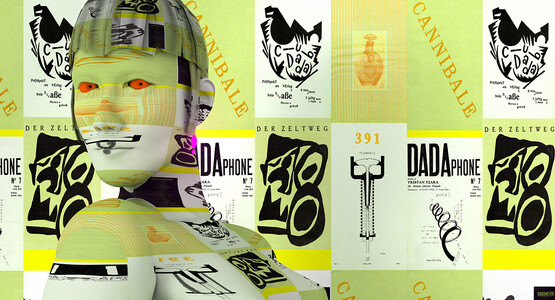

In his 2016 essay ‘Invisible images (your pictures are looking at you)’, the artist Trevor Paglen wrote: ‘Over the last decade or so [. . .] human visual culture has become a special case of vision, an exception to the rule. The overwhelming majority of images are now made by machines for other machines, with humans rarely in the loop’.1 From optical character readers to facial recognition, more and more images are being produced for computers rather than people. This means that machines are informed about the world – and about us – in ways that we can barely fathom. Citing Paglen’s statement as a starting point, the curator of the online exhibition For Your Eyes Only, Domenico Quaranta, adds: ‘with the development of machine vision, visual culture has become a contested territory, and the human gaze and intelligence have become the minority group’. How, therefore, can one highlight human vision and resist the pervasive gaze of the machine? For this group exhibition, Quaranta invited thirteen artists to directly engage with this question: Morehshin Allahyari (b.1985), Sara Bezovšek (b.1993), Émilie Brout (b.1984) and Maxime Marion (b.1982), Anna Carreras (b.1979) FIG.1, Petra Cortright (b.1986) FIG.2, Francoise Gamma (b.1988), Theodoros Giannakis (b.1979) FIG.3, Kamilia Kard (b.1981), Jonas Lund (b.1984), Lev Manovich (b.1960), Petros Moris (b.1986), Katja Novitskova (b.1984) FIG.4 and Jon Rafman (b.1981) FIG.5. They emphasise how cultural and institutional context, personal histories, intertextual references, interpretive practices and value judgments influence design and its reception. The machine lacks such insights; subjectivity can be a feature as well as a flaw of human vision.

Although machines are often perceived as cold and distancing, digital art galleries can act as places for practitioners to discuss shared social and political concerns relevant to their practice. Community is at the core of Feral File, a digital art gallery and blockchain platform that launched in April 2021. Founded by Casey Reas, the artist and designer of Processing – an open-source software for visual artists that recently celebrated its twentieth anniversary – Feral File offers small, curated exhibitions. The gallery sells individual works as NFTs, offering them as multiples and lowering the price for the works as a result. In addition, all artists included in a show acquire an edition of each other’s works. This is aligned with the communitarian spirit of early web art, with an emphasis on open source and an enthusiasm for digital art’s lack of scarcity. Amid the capitalist transactionality emphasised in crypto art, Feral File uses blockchain to introduce a gift economy for artists. It is appropriate that a gallery disrupting the standard exchanges of blockchain hosts an exhibition intervening in the prevalence of the gaze of the machine. Both reinsert and reconsider human desires, dependencies and opportunities.

The Iranian artist Morehshin Allahyari is well known for her interventions in digital colonialism, producing works that reflect on how information technologies are deployed to reproduce colonial power relations. ماه طلعت، (Moon-faced) FIG.6 continues this work by reversing the gender bias that was introduced into Persian society by Western influence. In ancient Persian literature, ‘moon-faced’ was a genderless adjective used to define beauty, whereas in contemporary Iran it refers solely to the beauty of women. In the Qajar dynasty, portrait paintings were historically characterised by a cross-gendered ideal of youthful beauty. However, modernisation, as well as increasing artistic and political exchange between the West and Iran, prompted the court’s embrace of realistic painting and photography, ending the prevalence of ‘gender-undifferentiation’. In this project, Allahyari uses artificial intelligence – which is so often maligned for producing sexist and racist presentations – as a way to reinstate these ideals. Using a multimodal AI trained on the Qajar Dynasty painting archive (1786–1925), her videos reproduce the once-genderless portraits, resisting the Western gaze that was imposed upon the painting tradition. When humans partner with machines they can produce visualisations that overcome the historically embedded bias that they each otherwise reproduce. Mutual effort, it becomes evident, is arguably our best strategy.

Lev Manovich is a leading theorist in the field of new media and digital visual culture, whose work has encouraged scholars to reconsider analytic approaches to digital imagery. One Million Manga Pages FIG.7 is a data visualisation based on research that he conducted in 2010 into manga styles from Japan, China and Korea from 1973 onwards. Manga are known for their surrealist graphics and, as with many comics, for being largely dismissed in the study of Western art history. However, this work does not simply reclaim a ‘low’ art form or celebrate the connoisseurship of fans. Manovich’s research uncovers a fundamental problem with the concept of style: it is ‘not appropriate [when] we consider large cultural data sets. The concept assumes that we can partition a set of works into a small number of discrete categories. In the case of our one million pages set, we find practically infinite graphical variations. If we try to divide this space into discrete stylistic categories, any such attempt will be arbitrary’.2 Manovich asks us to reconsider style as a governing feature of art-historical classification. There may be those who question whether data visualisation qualifies as a work of art; Manovich’s research prompts such sceptics to provide specific definitions, in turn, highlighting that boundaries are more often based on subjective sensibilities rather than objective references. This is not a dismissal but precisely where human vision prevails.

A Rose by Any Other Name FIG.8 by the artist Kamilia Kard is a 3D model of interconnected roses in different fleshy tones, which spring into dynamic motion in response to the user’s mouse or touchpad. At certain angles, shadows appear, presuming an unseen light source. Magnifying the buds and leaves reveals small tattoos, a form of body art that can act as a gesture of individualism or solidarity, dependent on choice and context. Over millennia, the rose has symbolised regeneration, love of all kinds and even blood. As often occurs in interactive or programmatic digital art, over time the motion of the flowers comes to resemble intentional, autonomous interactions, with consequent implications of connection and pain as they touch and repel one another. In literature the presence of the rose has been used to question the relationship between referent and reference:

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other word would smell as sweet.3

The vast landscape of signification and emotional implication is not accessible to the machine.

A similar struggle around designation arises in sextape (2021) by the artist duo Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion. In this video work, the artists have manipulated an amateur pornographic video with deep fake technology, altering the faces of the anonymous couple to resemble their own. According to the artists, sextape addresses two ‘radically opposed strategies of reputation-shaping’: revenge porn and the voluntary leak of documents by public figures in order to ‘gain credibility and media visibility’. It is the Janus face of our lives; our on- and offline activities are not distinct but coexistent and for both, context produces meaning. A social media algorithm would feasibly tag this as a pornographic video; it is only the exhibition setting that differentiates it as a piece of video art. The philosopher George Dickie pointed out the significance of context and industry recognition in his essay ‘The new institutional theory of art’.4 Although many have been troubled by the role of the ‘gatekeepers’ that he identified, his theory also reinforces the value of humans in the process of judgment.

The philosopher and art critic Arthur C. Danto proposed something similar, which Jonas Lund includes in the introduction to his work Smart Cut FIG.9: ‘To see something as art requires something the eye cannot decry – an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld’.5 This was, in 1964, a radical statement that set out how contemporary aesthetics are defined by institutions that make up the ‘artworld’. Machines, however, do not have this context on which to rely and are trained to use aesthetic criteria in determining value. AI works of art stem from data sets that are typically compiled by humans, who also control their outputs. This famously occurred when the French collective Obvious trained a generative adversarial network (GAN) on fifteen thousand portraits from WikiArt for their image Edmond de Belamy (2019), which sold at Christie’s for nearly half a million dollars.6 Lund has been experimenting with manipulating parameters in computer systems for years, producing abstractions that are based on pre-existing works of art, which he has, as he states, ‘optimized for market success’. For Smart Cut Lund took his previous abstractions and applied an algorithm to piece them together into an animation. Lund does not consider the work to conform to his theory of art, however it is clear that the machine has no system (yet) to determine its place within any established system of art history or theory.

For Your Eyes Only highlights how the notion that subjectivity is a problem to be overcome is precisely what we may now wish to reassess. Quaranta identifies the ambiguity of images as part of their communicative power. Our subjectivity may be the source of negative social hierarchies and biases but it is also the source of significance. If something is flawed that does not make it worthless; it can be the basis for creativity. These emergent technologies and computational practices serve a purpose, but our wellbeing is not a major consideration.7 The same is true of many human authorities. Perhaps a resolution lies not in one or the other, but a greater consideration of both. Doing so requires engagement, not dismissal. It requires attention, not derision. We need to reflect on the machine and ourselves, to see the possibilities we can yet generate.