Monstrous spectacle

27.10.2021 • Reviews / Exhibition

by Peter Miller

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 01.02.2023

In the painting Bacchanal FIG.1 by the Barbados-born artist and educator Paul Dash (b.1946) a throng of revellers are shown twisting, tripping and shaking against one another. Ochres, olive greens, dusty pinks and powdered blues are applied to the canvas to describe their costumes. The repetition of these tones creates a sense of rhythm, especially when seen from a distance, stimulating the apparent motion of the dancer’s bodies. This is at the cost of their increasing abstraction, which climaxes towards the edges of the canvas, where the brown of the revellers’ skin is layered gesturally over reds and lavenders. Bacchanal imagines a joy so feverous that it resists representation.

The crowd and the pleasures of its movements are key themes of Paint Like the Swallow Sings Calypso at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge. The exhibition explores the themes and forms of Carnival, centring on the work of three Caribbean artists living and working in the United Kingdom: Dash, the Trinidad-born poet and painter John Lyons (b.1933) and the Jamaican-born children’s author and artist Errol Lloyd (b.1943). It takes a global, diachronic approach to Carnival, bringing together forty-six works from artists as diverse as Barbara Hepworth (1903–75) and Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1564–1638). Curated in collaboration with Habda Rashid, the Senior Curator of Contemporary and Modern Art, Dash, Lyons and Lloyd have selected works from the collections of Kettle’s Yard and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, to be shown alongside their own. This approach affords the three artists the unique opportunity to contextualise their practices, situating them in a wider tradition of masquerade, revelry and pre-Lenten celebration. Broadly speaking, the exhibition is organised into three thematic areas of concern: the historical origins of Carnival, its spiritual and religious resonances and its proximity to the natural world.

The first gallery largely focuses on historical works, which are shown in dialogue with recent paintings by Dash. The engraving A Dance of Fauns and Bacchantes (after 1516) by Agostino Veneziano (1490–c.1540), for example, is a light-hearted pastoral, couched comfortably in the Western art-historical canon. It poses a provocative counterpoint to Dash’s mixed-media work Carnival Troupe Pays Homage to the Ancestors FIG.2, the solemnity of which is characteristic of a Caribbean Carnival tradition that approaches joy and pain simultaneously. The Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite, for example, interpreted the limbo dance, which is often performed during Trinidad and Tobago’s Carnival season, as ‘a necessary therapy’ to ‘the cramped conditions between the slave-ship decks of the Middle Passage’.1 Here, the gallery space becomes a polyphonic space in which traditions from across the globe sit with and decentre one another as equals. In this way, Paint Like the Swallow Sings Calypso reflects the scattered history of Carnival itself, one that stretches from the ecstasies of Saturnalia to the catharsis of Shrovetide, and from the protests of Notting Hill to the samba of Rio de Janeiro.

Further connections between Europe and the Caribbean are realised as the viewer moves through the gallery. Francisco Goya’s (1746–1828) Soplones, plate forty-eight of his series Los Caprichos (1797–98), finds a parallel with Lyons’s woodcut Soucouyant and Jumbie Bird. Both works portray demons and mark the significance of mischief, magic and folklore to the Carnival tradition; in Trinidadian mythology, the soucouyant is a jaded spinster who turns into a bloodsucking fireball at night. The theme of spectacle is also addressed in another unlikely pairing: Le bal masqué (1782) by Jean-Michel Moreau (1741–1814) and Dash’s The Float FIG.3. Moreau achieves the grandeur of a late ancien régime ballroom using linear perspective; a sense of depth is established through a series of arches and a mezzanine in the distance, the presence of which is a reminder that the masquerading figures in the foreground are being watched. The Float, a pen-and-ink drawing of a Carnival raft being built, is similarly focused on the physical structures that facilitate moments of spectacle. While making the drawing, Dash pasted paper over areas that he was unhappy with, creating an uneven surface. Such textural scars draw attention to a process of artistic construction that recalls the building of the float itself.

Lyons’s and Lloyd’s works are the focus of gallery two, where they are accompanied by a roster of more modern artists, including Stanley William Hayter (1901–88), Fritz Möser (1932–2013) and Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011). Despite this period shift, there is a continuity between the galleries, particularly in the excerpts from the volume The Carnival Trilogy (1993) by the Guyanese author Wilson Harris inscribed on the walls: ‘Fly, sunflower, star, feather, crocodile, cannon – to list a few spectres that haunted the route of the procession’.2 These lyrical citations from Harris reflect the media – literary, visual and musical – that constitute and inform the Carnival tradition. Indeed, the title of the exhibition, the gallery text explains, is ‘a reference to The Mighty Swallow, the performance name of the Antigua and Barbuda calypso musician Sir Rupert Philo’.

The inclusion of Harris’s writings also reflects his historical relationship to Dash, Lyons and Lloyd. The Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) was a gathering of writers, poets, artists, academics and activists that took place largely in London between 1966 and 1972. It was founded by Brathwaite, the Trinidadian writer and publisher John La Rose and the Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey. Harris was a significant member of the movement, as were the artists central to this exhibition, to varying degrees. Lloyd was the most prominent of the three, taking part, as the scholar Anne Walmsley explains, in CAM’s first artists’ symposium in June 1966.3 Dash attended the second CAM conference in August 1968 and is referred to by Walmsley as a ‘core’ member by January 1971, whereas Lyons’s presence was more marginal.4 In an interview recorded for the exhibition he explains that he was ‘out of London’ but nonetheless ‘in the spirit of it’.5 The context of CAM certainly illuminates the proud celebration of Caribbean Carnival that is on view here. In a paper delivered at a CAM meeting on January 1967, the Jamaican sociologist Orlando Patterson admitted: ‘In my experience, yes, there is a Carnival spirit and we do have a hell of a lot of parties, far more than the average British person; and we do make a lot of noise’.6

Impressions of partying and noise are particularly apparent in Lyons’s painting Mama Look A Mas Passin FIG.4, in which masqueraders spread their palms and throw their arms up in the air. Lyons’s brushwork is choppy and loose, letting emeralds, blood oranges, pinks and yellows vibrate against one another. The artist’s gestural expression shares the freedom and playfulness of his revellers, and yet he cloisters a jester in the top-right corner of the canvas, a figure built out of crude, mint-green lines. The coarseness of the jester’s costume mocks any form of sincerity that might be left in masquerade; it is a reminder not to take dressing up and pretence too seriously.

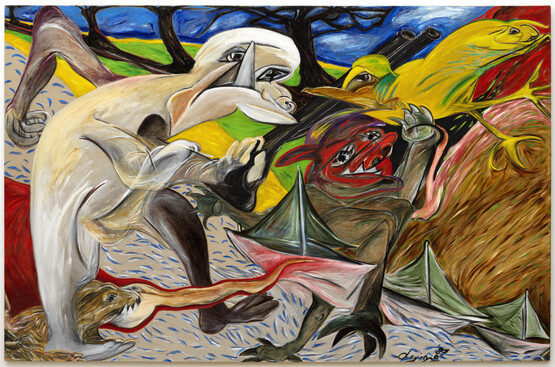

By comparison, Lyons’s earlier painting Eloi! Eloi! (Lama Sabachtini) FIG.5 is far more solemn. It depicts a brutal crucifixion, with Christ arching his back on the Cross in pain. In the wall caption, Lyons relates the agony of this biblical moment to the ecstasy of the dancing body in Carnival. His suggestion that brutality and bliss might be similar in some way, not just simultaneous as in the case of Brathwaite’s limbo, is also implied elsewhere in the show. Brueghel’s A Village Festival, With a Theatrical Performance and a Procession in Honour of St Hubert and St Anthony FIG.6 is a monumental work. In the painting’s bottom-left corner, a group of village dancers are entwined with a gang of street fighters, forming an S-shape. It is unclear whether the villagers are frolicking with glee or fleeing from the fight; perhaps it is both. The energy of their movements, regardless, is matched by the momentum of the ruffians’ punches. Lyons and Brueghel share an interest in the potential for violence to resemble delight – an affinity made uniquely possible in the extraordinary, inverted world of Carnival. It is an example of what Mikhail Bakhtin, writing in 1963, referred to as ‘carnivalistic mésalliances’, a phrase that describes the combination of phenomena that would be incompatible in a ‘noncarnivalistic’ reality.7

The complex agony of Eloi! Eloi! is exchanged for a more sobering pain in The Deposition FIG.7 by Graham Sutherland (1903–80), another Crucifixion painting hung nearby. Sutherland’s rendering of the Cross and the various saints that cling to it betray a Cubist influence. His painting is the beginning of a more concerted move into abstraction at this point in the exhibition: works by Hepworth and Avinash Chandra (1931–91) follow on the adjacent walls. The jilted rhythms and whimsical, humanoid forms of Chandra’s Design FIG.8 sets the tone for the explorations of dance pursued by Lloyd in the final part of the exhibition, as well as the organisation of these works of art on the wall.

The majority of Lloyd’s works are modest in size compared to the large-scale portraiture of Lyons. His watercolours Notting Hill Carnival – Mask (2001) and Notting Hill Carnival – Olmec (2001) offer delicate descriptions of costume details. Lloyd’s precision is a dedication to the intricate skill, time and care demanded in Carnival’s production. The watercolours are hung in a collage fashion, interspersed with Lyre Bird (c.1943) by Ceri Richards (1903–71) and La Tortue (1940) by Nat Leeb (1906–90). The brisk mark making of Richards’s bird portrait, which reflects an engagement with nature that is present throughout gallery two, works well with the abstraction of La Tortue, a painting that roughly repeats the scutes of a turtle shell against soft greens and bright yellows. The effect of the hanging is similar to the appearance of photographs on the walls of a family home. The intimate and personal quality is grounded in Lloyd’s process: he painted many of his studies from photographs he had taken during visits to the Notting Hill Carnival in the 1980s.

The attention that Lloyd gives to individual costumes and details is carried through into his ambitious Notting Hill Carnival IIC FIG.9, which closes the exhibition. The grid layout of close-up portraits allows for the coexistence of multiple experiences of Carnival while retaining an emphasis on the individual. Although Lloyd’s interpretation of Carnival diverges from the crowded scenes of Dash’s, the primary blues, reds and yellows nonetheless disrupt the figurative montage of dance troupes and side glances. These basic hues augment, ironically, the vivacity and variety of those troupes. Abstraction is deferred to once again as a direct path to the ineffable colour of Carnival.