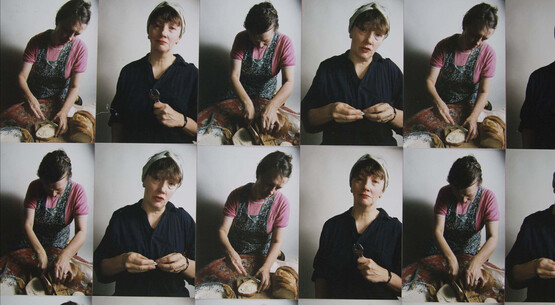

Keith Kennedy’s group photography and the therapeutic gaze of Jo Spence and Rosy Martin

by George Vasey

by Marilena Borriello

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 05.06.2024

As an artist ahead of her time, Lynn Hershman Leeson (b.1941) has long been unfairly overlooked. In the 1960s, at the outset of her career, the art world was staunchly anchored to medium specificity and struggled to grasp her merging of art and technology. What particularly eluded critics at the time was the fact that the technological elements in her works could not be understood through the lens of a single genre or category. Rather, because her message was primarily political, they had to be considered within a broader social context. Hershman Leeson’s involvement in the protests of 1968 and the Black Panther Party, as well as her contributions to the development of cyberfeminism alongside Donna Haraway, are well documented. However, what inherently politicises her output is her ability to carve out spaces of dissent and resistance, challenging established conventions and questioning power hierarchies.1 For over five decades Hershman Leeson has explored complex themes, such as gender, identity and the increasing impact of technology on privacy. Indeed, her work offers insights into how a panoptic society might morph into a paranoid one – a society in which every individual develops suspicions and ultimately becomes a target.2

It is precisely this political dimension of Hershman Leeson’s practice that is at the heart of Are Our Eyes Targets? at the Julia Stoschek Foundation, Düsseldorf. Although the exhibition opens with a number of early works, such as the mixed-media sculpture Paranoid FIG.1 from her Breathing Machines series (1965–2022), it avoids a chronological sequence. This is especially apt for Hershman Leeson, as she often revisits and updates previous projects, so that her her artistic corpus manifests as a unified and branching organism. The centrepiece of the exhibition is a reworked version of The Electronic Diaries of Lynn Hershman Leeson 1984–2019 FIG.2 FIG.3, a multi-channel installation that also inspired the Julia Stoschek Foundation’s parallel exhibition Digital Diaries (11th April 2024–2nd February 2025), which explores the evolution of the diary form in video and digital art from the 1970s to today.3

Since the 1980s Hershman Leeson has recorded solitary video confessions in front of a camera in her studio FIG.4, and they constitute a fundamental pillar of her practice. Identity control and the limitations of autonomous thought have been constant themes for the artist, which resonate particularly well with the videotape format. In The Electronic Diaries Hershman Leeson seamlessly merges personal narratives with a detailed analysis of her artistic output. In the fourth segment, Shadow’s Song, which comprises footage from 1997 to 1999, the artist reflects on her bond with video diaries, acknowledging an intimate, almost symbiotic relationship with technology. This is reflected in her exploration of the intersections between humans and machines and in her probing of the boundary between the virtual and the real: ‘A cyborgian future. That’s what I see in this camera’, she affirms prophetically.

Considering her adoption of modes of self-observation, Hershman Leeson’s work can be understood in the context of the ‘aesthetics of narcissism’, as defined by Rosalind Krauss.4 However, it is crucial to note that her self-reflexivity goes beyond simply using video as a mirror of the self. For the artist, the medium also reflects and embraces the wider sociocultural dynamics that shape her diaristic confessions. In her videos, she positions the self not as a fixed entity but as a social process that is constantly influenced by institutions and technologies. This in turn allows for a broader and deeper understanding of her own practice. In particular, Hershman Leeson’s diaries have provided the opportunity for her to challenge the various forces that have exerted power over her in the past. Viewed in this way, her seemingly narcissistic approach becomes a tool of knowledge and rebellion against the dynamics of privacy and identity control: a form of political resistance.

Another unique element of Hershman Leeson’s self-exposure is the participatory nature of the observer in her works. By placing them in a voyeuristic position, she invites the viewer to reflect on the act of seeing and become aware that their gaze can be subject to invasive and intrusive observations. Giving the exhibition its title, Are Our Eyes Targets? FIG.5 is a digital print of a frame from Hershman Leeson’s Deep Contact (1984–89) – the first work of art to incorporate touchscreens – in which the participant is invited to touch their ‘guide’ Marion. Are Our Eyes Targets? signals the observational dynamics of the original installation, in which the viewer’s engagement with Marion was captured by surveillance and integrated into the scene itself.

The acts of observing and being observed are profoundly influenced by sociocultural factors, which Hershman Leeson seeks to reaffirm her control over. Through the production of interactive cyberart, the artist rejects the passive role engendered by voyeurism and claims her independence and the power to redefine her own identity and visual representation. CybeRoberta FIG.6, for example, is a telerobotic doll resembling Roberta Breitmore, the artist’s alter ego, which she often performed in the 1970s. The doll’s eyes have been replaced by cameras: the left is a security camera that takes photographs and the right functions as a webcam, allowing remote observation of the space. The photographs are sent to a website, where visitors can also click on the doll to rotate its head 180 degrees. This allows the observer to temporarily wear a cyborg mask to exercise surveillance – a mask that, as Hershman Leeson emphasises, is liberating because it offers the possibility of authenticity.5

This exhibition, and Hershman Leeson’s work more generally, is a clear invitation to reflect on the ethical responsibility of our gaze, urging us to examine how our behaviour may perpetuate unjust surveillance and control systems. The film Shadow Stalker FIG.7 – one of the most recent works on display and originally part of a larger interactive installation – raises crucial questions about AI-based surveillance and the use of historical data in predictive policing systems. It explores the vulnerability of individual identity and privacy in today’s digital age, addressing the ubiquity of unregulated algorithms that allow digital tracking and racial profiling for crime prevention.

Are Our Eyes Targets? effectively showcases Hershman Leeson’s central artistic concerns. It underscores her interest in a direct dialogue with the public, which prompts a reassessment of the viewer’s relationship with their environment and a critical analysis of what constitutes ‘reality’. In this way, she emphasises the importance of taking ownership of one’s narrative and empowers individuals to shape their perceptions and interpretations of the world. Furthermore, it unveils the image of an artist who has transformed scepticism and cultural prejudices into a radical revolution, ultimately enabling her own well-deserved recognition for playing a pivotal role in cultural history. Always prescient, her work confirms what we now know to be true: autonomy of thought is the most significant form of freedom. It is the quintessential political act of resistance.

Lynn Hershman Leeson: Are Our Eyes Targets?

Julia Stoschek Foundation, Düsseldorf

11th April 2024–2nd February 2025