Keith Kennedy’s group photography and the therapeutic gaze of Jo Spence and Rosy Martin

by George Vasey

by Maximiliane Leuschner

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 29.06.2023

Although Hannah Villiger (1951–97) is not a household name today, between the early 1980s and her untimely death at the age of forty-five, the Swiss artist commanded the attention of the international photography scene. Villiger worked between the traditional genres of photography and sculpture, carving out a niche through her unique amalgamation of the two. She treated the photographic print as raw material and translated sculptural techniques, such as removal or carving, into her editing process. The photographer Daniela Keiser (b.1963), who was taught by Villiger at the Schule für Gestaltung Basel, recalls the artist’s statement that ‘photography is sculpture’ (p.74).1 During a residency at Istituto Svizzero, Rome, in the mid-1970s, Villiger captured transitory processes with her Nikon camera, including the burning of palm fronds FIG.1, the action-reaction of boules and cloud-like jet streams in the sky. These photographs prefigured a practice that prioritised fragmented stillness at a time when performative agency was prevalent in the art world.

However, it was not such process-orientated photographs but rather the artist’s enlarged and aluminium-mounted Polaroids – a technique that she first developed during a period of convalescence from an acute bout of tuberculosis in 1980 – that initially bought her international acclaim. While hospitalised in Basel, Villiger turned her camera towards herself, taking pictures of her body overhead or at arm’s length.2 Later, in 1983, she would muse ‘Ich bin die Skulptur’ (‘I am the sculpture’) in one of her Arbeitsbücher (workbooks), of which over fifty survive.3 The Polaroid SX-70 camera and the popular 778 film served as her primary tools – her pigment, as she alluded to in a conversation with Bice Curiger – allowing her to correct photographs immediately in her hospital room, rather than relying on a lengthy development process in an external studio.4 This also gave way to Villiger’s specific working methodology, which incorporated sculptural techniques, such as cutting off the iconic white frame of the Polaroid. The artist would then enlarge, print and mount her carefully selected Polaroid images on aluminium, which she configured into grids of up to fifteen panels. Villiger has also been known to group her images in alignment with Classical sculpture: the photographs titled Arbeit (Work) FIG.2 often show elements of her face, whereas those titled Skulptural (Sculptural) FIG.3 reveal views of her feet, torso or genitals.5

More than twenty-five years after the artist’s death, and twenty-two after the influential exhibition 1/Bruchteil eines Portraits, vielleicht (1/Fragment of a portrait, perhaps) at Kunsthalle Basel, Villiger is the subject of a retrospective at Muzeum Susch in her native Switzerland.6 In Amaze Me the curators, Madeleine Schuppli and Yasmin Afschar, have attempted to reframe Villiger’s practice in the context of contemporary sexual identity and body politics, smartphones and technological developments, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns.7 Amaze Me also forms an integral part of the museum’s dedication to champion under-represented women artists, including, most recently, Feliza Bursztyn (1933–82) and Heidi Bucher (1926–93).

Rather than a chronological hang, Villiger’s works have been arranged in thematical groupings over the three floors of the maze-like former monastery. The large gallery on the ground floor introduces the artist’s iconic block formations from the 1980s. Here, the curators juxtapose one of the artist’s earliest works of this kind FIG.4 – concerning the ostensible banality of queer domesticity with her then-partner, the gallerist Susan Wyss – with two grid-like structures from the end of the decade, Block XIII (1989), in which the artist combined close-ups of her head and torso with those of her feet, and Block III (1988), which shows variations of the artist’s armpits and elbows FIG.5. Although these works do share a certain playfulness, this presentation creates unintended narrative patterns in the unconnected images. Here, they appear to develop a life of their own, both in the exhibition, where they conjure impressions of a similar genesis by virtue of their arrangement, and in the catalogue. For example, Emily Butler’s contribution, ‘HANNAH: performance and palindromes’, likens Villiger’s early sculptural impetus in the Arbeit (Work) series to the performative and conceptual work of Eleanor Antin (b.1935), particularly her thirty-seven-day-long endeavour to lose ten pounds in Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972).8

Although ostensible visual similarities, including the grid-like arrangement of the photographs, might in some ways align Antin’s documentary study with Villiger’s photographs, their individual impetuses point to significant differences. Carving was born out of a desire to subvert the medium-specific nature of the Whitney Annual, which alternated between painting and sculpture in the 1960s. She chose to submit a series of photographs that recorded the effects of crash dieting on her body, with the intent to mould herself into a Classical figure. In her essay, Butler highlights how Antin’s endeavour is a ‘performance of pain and gender [...] whilst at the same time highlighting society’s tendency to objectify women since Antiquity’ (p.84). By submitting thirty-seven photographs taken on consecutive days, Antin made the physical changes to her body public. Villiger’s photographs, on the other hand, were born out of technological facilitation and – contrary to the widely accepted narrative that they arose from a desire to record her crip body in hospital – the majority of her early works taken during her convalescence centre on close-ups of her face, including the eye area, nose or mouth, rather than the artist’s entire body. Moreover, according to Claudia Spinelli, Villiger chose not to show her post-partum body following the birth of her son.9 Similarly, the images taken shortly before her death FIG.6 show the contours of a fragile physical form shrouded in textiles rather than images of the actual body itself.10 Unlike Antin, Villiger treated her Polaroid prints of her body – not solely the body itself – as a material. By correcting the photographed angles, she edited these into configurations with no reference to the conception of the images. As such, Villiger heavily controlled which images were made public and was both incredibly private and selective with what she shared in her assemblages.

Another repositioning – of the thematic representation of skin – meanders throughout the museum’s three floors. Here the curators borrow from an essay in the 2001 catalogue raisonné, Griselda Pollock’s ‘The body, my body, her body’, in which the art historian frames Villiger’s practice as ‘a new alphabet composed of defamiliarised body elements. Each body part comes fresh and emptied before us, to be combined in an unfamiliar syntax that does not add up to the bodily grammar of Western classical sculpture’s vision of the female body’.11 Although, with regards to skin, Villiger chose a more conceptual definition. Included in Amaze Me are her early experiments with surfaces, including a series of ‘tree skinnings’, in which the artist removed the bark from branches and trees and collaged or sewed them onto paper FIG.7. These are shown in a room with two watercolours of a palm frond and a pair of jeans that the artist fashioned during her residency at Istituto Svizzero in the same year. Later photographs, such as Bildhauerei (Sculpture) FIG.8, highlight the painterly qualities of freckles, which in this case are compared to the surface of strawberries. The thematic unfolding of skin in Amaze Me is one of the first successful attempts to position Villiger’s sculptural practice in its entirety beyond its photographic origins, which was well established during the artist’s lifetime. It follows two recent reconsiderations of the artist’s work, including the Art and Choreography exhibition at Kolumba Museum, Cologne, in which Villiger’s Arbeitsbücher and sketches were first presented as choreographic scores alongside her photographic blocks.

A similar effort was made in the 2021 retrospective Works/Sculptural at the Istituto Svizzero, which placed a particular focus on Villiger’s two-year residency at Villa Maraini. Thomas Schmutz’s essay in the accompanying publication set the precedent for how to introduce Villiger’s work to a newer, younger generation:

The communication of art always aims at a positive effect. Yet all too easily, well-intentioned yet imprecise pedagogical statements lead to misinterpretations of the artwork at hand. This is especially true of efforts to highlight the present-day relevance of artworks made in the past.12

Alongside the comparative readings of Villiger’s images during her lifetime and today, Schmutz also delves into the artist’s decisions regarding different photographic processes, for example her characteristic use of the Polaroid camera. It is exactly this careful approach towards Villiger’s work that the curators hope to achieve in the exhibition under review, and at which they unfortunately do not succeed.

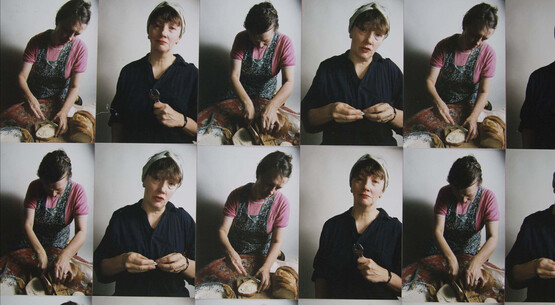

Firstly, and, perhaps, most obviously, the ubiquity of photographs on display is not contextualised within the neglectful treatment of photography in post-war Switzerland, apart from in brief in Afschar’s catalogue essay. Secondly, the curators have taken the fragmented nature of Villiger’s work – which this reviewer understands as an appproach towards archiving – as a point of departure to ‘complete it’.13 Schuppli and Afschar have commissioned three contemporary Swiss artists – Alexandra Bachzetsis (b.1974), Lou Masduraud (b.1990) FIG.9 and Manon Wertenbroek (b.1991) FIG.10 – to respond to specific aspects of Villiger’s œuvre, including the performative aspect of posing in front of a camera. Unfortunately, these commissions are contrived at best and do little to elevate Villiger’s work to that of an ‘artist’s artist’ (p.70), as outlined in Afschar’s conclusion. Instead, the exhibition would have benefited more from pairing Villiger’s works with selected historical works from her native Switzerland, for example, the queer photographs of Alex Silber (b.1950), with whom Villiger shared a flat in Rome, or Daniele Robbiani (b.1956), with whom she worked. The three artists were included in the 1988 exhibition Berührung Mann/Mann Frau/Frau at Kaserne Basel, which was one of the first shows in Switzerland to address the notion of queerness.

Amaze Me is a larger-than-life attempt to rehabilitate Villiger’s image. The spacious arrangement and the absence of distracting wall labels and texts allows time for the viewer to contemplate the works. However, while many issues that the artist addressed in her works appear contemporary – from her experiments with grid-like image structures to her sensual and intimate close-ups of her body as well as her approaches to queer sexuality and illness – the arguments posed in the exhibition would have benefited from further reflection. The curators attempt but do not fully commit to their efforts to reposition Villiger’s practice and often slide into speculative territory rather than work with the art at their disposal.