A Feminist Avant-Garde

17.08.2022 • Reviews / Exhibition

In her introduction to Feminist Art Activisms and Artivism, the editor Katy Deepwell writes that ‘art engages with feminist politics’ and ‘feminist politics reinvents art’ (p.9). Disabusing the reader of the idea that feminist art is an aesthetic style, the book is an anthology of issue-based artistic practices of the last few decades, which are more than ‘just an extension into art of the political agenda of the women’s liberation movements since the 1960s’ (p.9). Although the book distinguishes between then and now, there has nonetheless been a renewed interest in the then: the women’s liberation movement, as well as other liberation struggles of the 1960s and 1970s and the politicised artmaking of the time. This is typified in the recent attention paid to long-obscured artists in institutional programmes and commercial gallery rosters. However, it is the return to out-of-print publications that truly attests to the politics that inspired artists and prompted change in the art world.

Primary Information has led the way in this endeavour, publishing facsimiles of artist books, such as Michael Snow’s Cover to Cover (1975) and Renée Green’s Camino Road (1994), as well as small-run pamphlets like David Wojnarowicz’s In the Shadow of Forward Motion (1989). The publisher’s reprints also include some of the most important publications to emerge from the women’s liberation movement, including The New Woman’s Survival Catalog (1973) and, most recently, A Documentary HerStory of Women Artists in Revolution (1971). If The New Woman’s Survival Catalog – modelled on the counterculture magazine Whole Earth Catalogue – evidenced a universe of feminist services to emerge from the women’s liberation movement, A Documentary HerStory captures the early years of feminist activism in the art world, when the interaction of art and politics, as identified by Deepwell, manifested.

A Documentary HerStory of Women Artists in Revolution is a collection of documents – letters, newsletters, scripts for talks and press cuttings – gathered by a group known as Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), which included Muriel Castanis, Agnes Denes, Juliette Gordon, Dolores Holmes, Doris O’Kane and Lucy R. Lippard among others FIG.1. It records the group’s beginnings in the activist organisation Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), their attempts to reform the New York art world with a ten-point plan for equality and the formation of the Women’s Interart Center, an organisation devoted to supporting women artists FIG.2. Incredibly the documents derive from only three years of work, 1970–73, a period of intense change that prompted the book’s original editors, Janet McDevitt and Jacqueline Skiles, to note in their postscript dated 15th June 1973 that they were ‘proud and at the same time nostalgic’.1

The re-emergence of A Documentary HerStory in 2021 threatens to be nostalgic for the political activism of the 1970s, especially as it celebrates the Interart Center, which closed in 1981, while lamenting the failure of its proposed museum reforms. Nonetheless there are many documents that make for salient reading in the present, when museums and public galleries – especially in the United Kingdom with the Art Council’s Let’s Create Strategy for 2020–30 – have a greater responsibility to their communities and the support of disenfranchised artists. This collection raises important questions about institutional gatekeeping. We learn about curators who suggested that ‘interested museum representatives’ research under-represented artists, while at the same time rejecting demands for fifty per cent women artists and fifty per cent Black artists FIG.3. While WAR interrogated the museum’s defence of ‘quality’, museum workers remarked on how these acts of opening up would disenfranchise other artists. If museums and galleries now check boxes that enforce these once rejected quotas, then the fact that such demands are still relevant today speaks to the power of institutions to maintain the status quo; taking on the critical work does not necessarily result in broader cultural change.

Although A Documentary HerStory is a record of struggles and strategies past, there are relevant lessons about solidarity. The page of Cindy Nemser’s Arts Magazine article ‘Forum: women in art’ (1971) highlights the vagaries of political recognition among women artists. For some, such as Grace Hartigan, ‘the subject of discrimination is only brought up by inferior talents to excuse their own inadequacy as artists’, whereas others, like Lil Picard, describe being ‘told bluntly by galleries “We don’t take on women”’.2 Perhaps most stirring is Muriel Castanis’s preface, which opens the volume with a brief history of the early years of women’s liberation:

You see, when women come together as they did in W.A.R. to communicate, a piece of the wall was broken down. More and more of that wall has been chipped away as more and more women meet to talk. It’s a relatively new experience and communications in a new language are sometimes slow and difficult. But these internal difficulties are simply reflections of the adjustments women are making in terms of trusting and respecting themselves and other women as instruments of viable change. As women continue to grow they are learning to free themselves of old patterns which are as antiquated as the male patterns from which they are derived. The movement’s goals is [sic] to make significant change both inside people’s heads as well as outside in the world.3

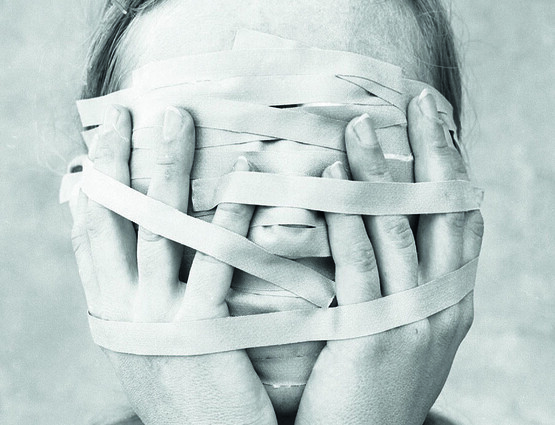

Talking together was a hallmark of women’s liberation. The organisational form of consciousness raising – a group of women speaking of their oppression together – was foundational to the movement and endlessly rearticulated in other group structures, from exhibitions to anthologies and beyond FIG.4. Working together was the means of forging change ‘inside people’s heads as well as outside in the world’. The emphasis on group work is a significant reminder for the present moment, but perhaps most important is the recognition that ‘communications in a new language are sometimes slow and difficult’. A Documentary HerStory advises that political solidarity is hard. For contemporary readers, it also describes some of the fictions and blind spots that were established in the early years of women’s liberation and that continue to exclude. Biological gender is taken to be axiomatic, while whiteness is the implicit norm and racial difference is displaced, as one document notes: ‘the committee felt that that a black woman artist should be considered a woman since this involved a more profound discrimination’.4 Alongside the passages that attest to oppression within the movement, other texts evidence the utopian possibilities of feminism when open to the undefined:

We are on the threshold of the unknown quantity in us, X of the equation yet to be discovered [. . .] Women are unliberated, and held back from full self-realisation, because of their conditioning, which makes culturally-transmitted characteristics [. . .] into innate feminine qualities [. . .] We therefore ask the museum to sponsor a program flexible enough to open up possibilities for women as artists to fulfil their unrealised potentialities. X is the unknown quality in an equation yet to be resolved.5

Feminist Art Activisms and Artivisms, published by Valiz, acts as a response to these ‘unrealised potentialities’ of the 1970s. Through a combination of responses by artists, activists, writers and scholars, it confirms a shift from liberation consciousness to the expansive feminist standpoint of our contemporary moment. The book includes contributions from, among many others, the artist Michelle Williams Gamaker on her recent film trilogy Dissolution FIG.5; Rosy Martin on women and aging FIG.6; and Marissa Begonia from The Voice of Domestic Workers support network in conversation with the art writer Amy Charlesworth on their longstanding collaboration. Loraine Leeson provides an account of her decades-long-practice FIG.7; the artist group GraceGraceGrace outline their manifesto; and there are also essays by Alana Jelinek, Alexandra Kokoli and Elke Krasny.

As Deepwell argues, ‘art produced in this way is not just about producing sympathy or empathy for “good causes” or pre-existing issues’ but ‘encouraging us to see the world and how it operates differently’.6 Here feminist politics are not organised around a single idea of ‘woman’; differences of class, race, gender, sexuality, nationality and age are all explored by the contributors FIG.8 FIG.9. The book also traces the dispersed field of contemporary feminist praxis: independent projects, studio-based practices, works of art shaped by activism, community arts and art education. The risk of such a gathering is naturally one of dilution, however this volume presents the commitments and the conflicts of feminism. The accounts do not all agree; the authors present different investments and ways of working across a spectrum of sincerity and humour, solidarity and commitment, art and activism.

Feminist Art Activisms and Artivisms emerged from a conference and as such it offers a picture of contemporary feminism that is not shaped by a single editor – although it undoubtedly depended on Deepwell’s energy and expertise for its realisation.7 In the future, this book will be a record of the feminism of the moment, just as A Documentary HerStory is a chronicle of the early 1970s. There are points to critique here too. For instance, Deepwell’s introduction is generous in defining a container capable of holding on to a diverse, and at times directly conflicting, set of positions, but her turn towards Dimitris Papadopoulos’s ‘alter-ontological organising’ manifests as an evacuation of political struggle rather than an expansion.8 Deepwell quotes Papadopoulos’s advocation for ‘more-than-social movements’ that ‘do not attempt to contest power by organising protest; rather, they attempt to create the conditions for the articulation of alternative imaginaries and alternative practices that bypass instituted power and generate alternative modes of existence’.9 Although Papadopoulos’s position is suggestive of a path to move beyond the institutional protest that has so preoccupied women’s liberation, it also has the effect of dismissing the necessity of contesting injustice. Does this model work to abolish the carceral state? Does it eradicate the borders and conditions that perpetuate the migrant crisis? Does it encourage and allow for the support of trans healthcare? How can clashes within feminism be dealt with? How can ‘white feminisms’ be seen as more than a ‘term of abuse’, as Deepwell asks, and instead understood as the descriptor it is, whether for an exclusionary past or for an intersectional present?10

Both of these books are invaluable resources on feminist praxis – part of a tradition of documenting activist art that would otherwise go unacknowledged. The accounts offered in these publications contest institutional validation, they go beyond it and even, at points, expose it. Although they are records of activisms past and present, they also act as prompts and resources to consider, and reconsider, what feminism could be now and in the future.