Building a world after its end

by Anna Staab

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 14.12.2020

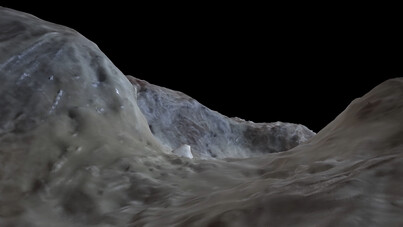

‘In what language does nature write its catastrophe? How to recount the story from the other side of disaster?’.1 Almost two minutes into its seventeen-minute runtime, this is the first sentence uttered in Archaeology of Sacrifice (2020) – a two-channel video installation with surround sound design by the Chilean artist Ignacio Acosta.2 Across the split screen, a green mineral rotates in front of a black background, interchanged with shots of a cloudy sky dotted with birds, waves lapping against a stony shore, details of rock formations, stones and waterscapes FIG.1. Close-ups alternate with wide perspective and panoramic views of a lake surrounded by mountains and forests FIG.2. An omnipresent, reverberating drone intermingles with the cries of birds and the sound of water; long, ominous pauses punctuate the voice-over narration.

In Archaeology of Sacrifice, the line between natural formations and human remnants are blurred. The film collages together various source materials relating to Mormont Hill, a limestone and marl quarry in the Swiss canton of Vaud. Acosta’s camera and drone footage, which captures the landscape and mining excavators at work there FIG.3 is spliced together with excerpts from a documentary about the excavation of a Celtic sacrificial site3 and digitally generated models of minerals FIG.4.4 The camera lingers over panoramas that soon begin to seem familiar and stones come to resemble portraits that we might enter into dialogue with, while people appear only as observers and collectors, as diggers and exposers. We see close-ups of brushes cleaning skulls FIG.5, tweezers arranging splinters, upper bodies shovelling in a dusty landscape and backs of heads at cluttered desks FIG.6. Their bodies are fragmented, reduced to a parasitic relationship with the landscape and its elements, artefacts and the machines and tools of extraction and excavation. Through this refusal of the human subject, the rock faces, dams, imaginary minerals, landscapes, fossils and water develop their own relationships, in which we all become intruders. By speculating on the language of nature and imagining that the ‘obstinate stone of the past demands justice’,5 the work evokes the autonomy and resistance of ecological forms.

Acosta’s installation presents the processes of knowledge production as creative acts and translations, rather than ones of recognition and reconstruction. At the same time, the work reveals its own modes of translation: firstly, the voice-over recites a text by Carlos Fonseca Suárez, originally written in Spanish, in Swiss French, whereas it appears in English and German subtitles on either side of the split screen. Secondly, it constantly transitions between micro and macro perspectives as well as archival material and digital models, enabling the viewer to reflect on the specific focus and blind spots of the relevant medium. While prolonged close-ups draw our attention to the structure of rocks and water movements, allowing us to consider them as readable objects with symbolic meanings, Acosta’s use of the panoramic allows us to perceive their location within an indivisible landscape, their interrelation and relativity to their environment.

As with Acosta’s earlier works, Archaeology of Sacrifice calls attention to the impact of the exploitation and extraction of natural resources.6 However, this work does so with a particular focus on the parallels between procedures in archaeology and mining. The archaeological distinction between ‘finds worthy of conservation’ and ‘obstructive material’ appears as intrusive as the economically motivated decisions and processes set out by construction companies. Both industries distinguish between coveted materials and ‘the rest’ that impedes its procurement; both extract only what they deem to be usable from its context. Although they may initially appear delicate, archaeological conservations can in fact match the brutality of detonations and extractions carried out by machines FIG.7 – they too leave ‘incision, cut and ruin’,7 resulting in the disruption of ecological balances that have evolved, in some cases, over thousands of years as well as symbolic meanings that have been ascribed to the site in preceding cultures. In addition, the sanctity of sacrificial rites and peace of the dead buried there become subordinate to archaeological interests on the one hand and economic motives on the other.

As such, the ‘remnants of a very modern crime’8 referenced in the video’s narration could refer to the wounds inflicted on the landscape through either exploitation or archaeological dissections. They leave incisions and gaps that enact irreversible change. These traces also symbolise potential sacrifices in the future. They expose unquestioned convictions about what is to be extracted, protected, lost or destroyed, as well as power relations that determine who is eligible to make such decisions. Present and future archaeologies become observable as fictions about what could have happened here and what might have been lost – geologically and anthropologically.

Archaeology of Sacrifice reveals the systems and beliefs that allow for distinctions to be made: between what is valuable and expendable; between a research object and its environment; and between truth and fiction. Instead of categorising, the installation interrelates the seemingly disparate; instead of incisions, it creates connections. Without denying its own parasitical links to extraction processes and excavations, the work draws on the mythology surrounding the sacrificial site, the aesthetic by-products of lime extraction, the persuasiveness of archaeological narratives and the perspectives set out in the cited documentary. Each observer, which now incorporates Acosta and his viewers, 'builds a world after its end'.9 Each develops their own definition – or rather, imagining – of preservation and sacrifice as well as that which might be the world, its end or its beginning.

Exhibition details

Ignacio Acosta: Archaeology of Sacrifice

Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen

18th September–6th December 2020

Footnotes

- Translated from the French ‘Dans quelle langue la nature écrit-elle sa catastrophe? Comment raconter l’histoire de l’autre côté du désastre?’ footnote 1

- Produced as result of the Scholarship 2020 of the ZF Art Foundation, filmed during Principal Residency Program, La Becque Résidence d’artistes, La-Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, and with the collaboration of the Musée cantonal d'archéologie et d'histoire/Lausanne. footnote 2

- Stéphane Goël, dir.: Le crépuscule des Celtes [The Twilight of the Celts], 2007, ARTE, Climage and Télévision Suisse Romande, available at https://vimeo.com/426252827, accessed 8th December 2020. footnote 3

- Footage created by Ignacio Acosta in collaboration with the artists Valle Medina and Benjamin Reynolds (Pa.LaC.E). footnote 4

- Translated from the French ‘pierre têtue du passé’. footnote 5

- See Acosta: ‘Copper Geographies’ published in TRANSFER Global Architecture Platform, available at https://www.transfer-arch.com/delight/copper-geographies, accessed 14th December 2020; and D. Chocano: ‘Ignacio Acosta’ published in Burlington Contemporary, available at https://contemporary.burlington.org.uk/reviews/reviews/ignacio-acosta, accessed 14th December 2020. footnote 6

- Translated from the French ‘incision, entaille et ruine’. footnote 7

- Translated from the French ‘traces d’un crime très moderne’. footnote 8

- The author here makes reference to the French ‘comment construiront-ils un monde bien après sa fin?’ footnote 9