Ignacio Acosta

by Diego Chocano

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 20.11.2019

Tales from the Crust is an exhibition of new and existing work by Ignacio Acosta that examines three cases of extractive violence in Andean Chile and Swedish Sábme. Across two galleries at Arts Catalyst, London, multimedia installations comprising interviews, films, maps and texts outline a series of strategies undertaken by local activists to counter the adverse social and ecological effects of mining. These acts of resistance confront those who value territory as commodity and see nature as an obstacle to be overcome in the perennial pursuit of progress.

The artist’s book Copper Geographies (2018) serves as an excellent starting point to the show, not only because it is one of Acosta’s oldest works but also because it serves as an introduction to the paradoxical conditions of modernity. The book outlines the role of copper in shaping the modern world, from its use in sheathing for imperial warships to the wiring within our computers and mobile phones. Acosta tracks the movement of mined copper from Chile to the United Kingdom, exposing the asymmetrical power dynamics that exist between these respectively peripheral and core centres of trade.

A visual essay that is punctuated by poetry and text, Copper Geographies illustrates the two very different consequences of this trading partnership. The second half of the book depicts the promise of progress fulfilled in the United Kingdom, with photographs of leafy post-industrial landscapes, the lavish mansions of copper traders and trading floors, where natural resources are turned into abstract commodities. The first section, however, depicts the world from which the raw material is mined. Photographs of dissected landscapes coupled with dilapidated and abandoned towns reveal the social and environmental costs paid by the Atacama Desert and the little monetary reward that the Chilean people have received in return.

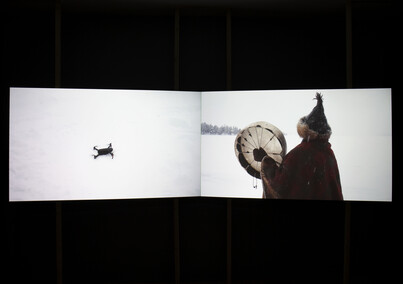

Acosta’s latest film, Drones and Drums (2018), outlines how the communities living with this destruction are responding. The double-channel installation FIG.1 follows Northern Sweden’s indigenous Sámi people and their struggle to save their ancestral lands from multinational mining exploration. Swedish Sábme, like many other areas of extraction, has become a digital colony: corporations utilise military technology such as drones to survey land and control dissenters, tools rooted in our colonial past. In Drones and Drums Acosta depicts how Sámi people have co-opted this technology to track the ecological degradation caused by iron mining.

Using drone footage shot by Sámi activists, the film depicts how a harmonious way of relating to nature has been suppressed to accommodate an extractive view. Forest landscapes are overpowered by a cacophony of chainsaws and falling trees; the sounds of a creek transform into the unsettling gurgling of man-made reservoirs and shots of pristine snow are abruptly juxtaposed with images of colossal concrete structures FIG.2. Rather than ‘condemning technology to its hegemonic use as surveillance’,1 Drones and Drums demonstrates how the Sámi people have appropriated and subverted it, shifting authority’s gaze back on itself and reclaiming what Nicholas Mirzoeff describes as ‘the right to look’,2 through which a disenfranchised subject becomes an active agent by looking where they were told not to.

In their struggle, Sámi drums have also become an important symbol of protest. These instruments – traditionally used as a way of achieving trance in ceremonies and rituals, allowing the spirit to ascend and travel – were prohibited throughout the Christian colonial project in Swedish Sábme. The film begins with the beating of a drum and a person in Sámi dress enveloped by snow and forest FIG.3. As the drumming intensifies, the camera ascends from the ground, transforming the viewer’s perspective into the aerial view of a flying drone. By using colonial technology to mirror Sámi ritual, the film presents an act of defiance against suppression and erasure. The drone therefore serves not only as a tool for counter-surveillance, but as a symbolic reclamation of ancestral rites.

These are perhaps the only two works in the exhibition that benefit from individual analysis. Acosta employs a constellatory model for the display, where the works, arranged across a long metallic structure FIG.4 serve as fragments best read in relation to one another. This encourages the viewer to posit a series of networked connections that ultimately provide a broader picture of the whole. One may question the impact of a time-lapse video that utilises satellite technology to track desertification caused by mines, displayed as it is on a small, low-hanging screen. However, read in relation to works such as Drones and Drums, it becomes part of a larger strategy of resistance.

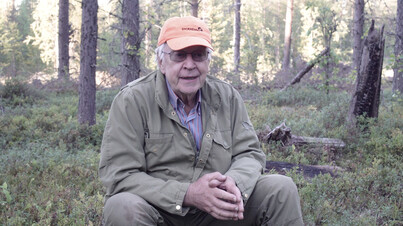

Similarly, the adhesive vinyl depicting a Eucalyptus forest (a tree not native to Chile that inhibits the growth of other plants) planted by mining companies to absorb the toxins emitted during extraction FIG.5, becomes a metaphor for the loss of indigenous epistemologies when examined in relation to Forest&Fires FIG.6. The latter video interview with a forester from Swedish Sábme outlines how local, effective ways of fighting forest fires are being forgotten and lost in favour of modern techniques that prove inadequate in the environment of Northern Sweden. The porous nature of Acosta’s installation allows for viewers to make connections between cases of extractive violence in seemingly disparate parts of the world, revealing an underlying logic.

As the global climate crisis becomes increasingly urgent and dissatisfaction over inequality bubbles into protest in Chile, Acosta has provided a space where a constellation of voices can converse and converge. This dialogue, made up of activists, indigenous groups, scientists and researchers, are the tales from the crust. Perhaps we should listen.

Exhibition details

Footnotes

- M. Gómez-Barris: The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives, Durham NC 2017, p.86. footnote 1

- N. Mirzoeff: The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality, Durham NC 2011. footnote 2