Brexit politics and feminist prophecies: Candida Powell-Williams’s tarot deck

by Edwin Coomasaru

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 18.12.2019

In the run up to the 2019 UK General Election, when competing visions of both the future and the past were shaped by endless opinion polling and press predications, Candida Powell-Williams exhibited The Gates of Apophenia (2019) at Bosse & Baum, London. The sculptural installation reimagines tarot cards with a feminist politics to explore the longstanding associations between women and magic. The project also reflects on speculative ideas of feminist or queer time, which challenge Enlightenment narratives of liberal progression, which have long been used to justify empire and oppression.

While fourth-wave feminist activism and art has taken up witchcraft as an image in recent years,1 as a magical practice tarot puts pressure on normative ideas of time. The card game originated in sixteenth-century Italy before transforming into a divination tool in eighteenth-century France, where it was infused with Egyptian symbols at the same time Napoleon was invading the country and looting their artefacts.2 Tarot then crossed the channel to the United Kingdom, a country that has long held the mainstream view that occult belief is the sole preserve of ‘primitive’ people or of ‘feeble-minded’ women, even while practices such as Spiritualism have enjoyed popularity in Britain (including among scientists) for centuries.3

The First World War, which saw a massive upsurge of interest in and use of magic amulets and divination, threw up profound problems for the idea of British ‘rationality’ and ‘modernity’.4 At stake was a narrative long used to justify racism, misogyny and homophobia both within the UK and throughout the empire: the claim that such subjects were hysterical or mentally ill and in need of control and containment from a strong paternal hand. The English traveller William Hepworth Dixon, for example, claimed in 1876 that ‘if we wish to see order and freedom, science and civilization preserved, we shall give our first thought to what improves the White man’s growth and increases the White man’s strength’.5 Indeed, during the war science took on a particular association with manliness, while the British Association for the Advancement of Science considered how the discipline could increase the ‘efficiency’ of empire.6

This worldview seems to have entered a profound crisis after the 2016 referendum, as fears and fantasies of British superiority on the world stage have struggled against the reality of negotiations with the European Union. Leavers and Remainers have often used the occult as a metaphor to attack each other as ‘diabolical’, possessed by ‘dark forces’ or ‘unleashing demons’.7 Remainers such as the former Prime Minister Gordon Brown complained, notably, that ‘our country turned its back [. . .] on our once globally renowned traditions of pragmatism, rationality and evolutionary progress’.8 A narrative of national decline can be found among Brexiteers such as journalist Douglas Murray who claims the UK is ‘going through a great crowd derangement’ as waves of feminist, anti-racist and queer activism over the last decade meant ‘people are behaving in ways that are increasingly irrational, feverish’.9

In 2018 BBC News warned that the UK was in the midst of a ‘tarot revival thanks to Brexit’.10 Such an upsurge in supernaturalism, however, predated the referendum. In the aftermath of the 2007–08 financial crisis and the brutal government austerity cuts to the welfare state from 2010 (which hit women and people of colour the hardest),11 an interest in magical practices such as crystal healing developed in a climate of precarious employment, falling wages and declining social security. The far right also turned to occult images – sharing satanic videos online – while anti-racist artists such as the poet and trans* activist Nat Raha took up the language of spells to critique the role of Enlightenment science and imperialism in histories of oppression.12 Recent books, including Gina Rippon’s The Gendered Brain (2019) and Angela Saini’s Superior (2019) argue that science has been profoundly shaped by prejudice, power and projection.

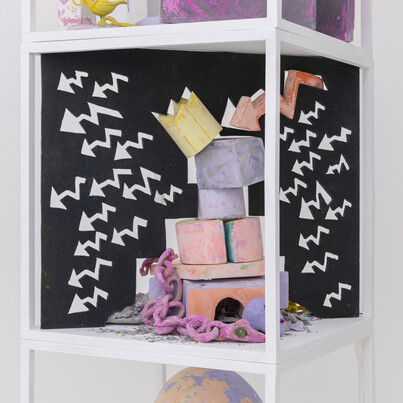

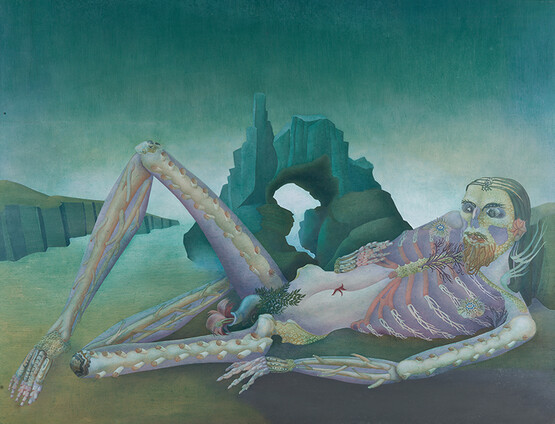

Given these complex connections between supernatural belief, economic inequality and re-evaluations of scientific objectivity, what might Powell-Williams’s installation at Bosse & Baum tell us about feminist ideas of time and history? The Gates of Apophenia brought together a series of sculptures, each representing a tarot card from of a set created by the artist as part of her project Unreasonable Silence (2019). Powell-Williams reimagined Pamela Colman Smith’s influential deck of 1910, transforming the symbolism to question the ways in which ideas of gender, sexuality and race shaped the original designs.

Tarot decks are not only meant to give a prophecy about the future, but also tell a story about the past: narrating the so-called ‘ages of man’ from prehistory to the present.13 The Gates of Apophenia challenges these myths, and questions how we conceptualise and narrate time itself. Alongside the installation, Powell-Williams gives tarot reading performances for the public, drawing cards and then walking the subject over to the corresponding sculptures to talk through the possible interpretative meanings of the reading. During the performances, there seemed to be resonances between tarot and psychoanalysis. If the analyst creates a stage for the patient to reflect on their feelings, traumas and anxieties in order to weave together a story about their own past and present, Powell-Williams’s performances offer a similar kind of possibility.

Psychoanalysis itself was born out of Spiritualism, and although Sigmund Freud publicly crafted an image of it as a ‘hard science’ for reasons of respectability, in private he felt it was inextricable from the occult, and believed in telepathy as thought transference.14 Apophenia (referred to in the title of Powell-Williams’s exhibition) is the practice of perceiving patterns where none may exist, something we may do as much on the analyst’s coach as in our everyday lives or the scientific laboratory. In fact, the writing of history itself is shaped by a tendency towards apophenia: transforming the complexity of lived experience into a set of neat narratives in which events unfold with a sense of inevitability.

We often assume our predictions about the future – whether they come from tarot readings or opinion polling – are more stable than they really are and as a result such narratives can profoundly structure our sense of reality. In his book Futurability (2017), the Marxist theorist Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi considers the ways in which the present contains multiple potential worlds. While noting that ‘power is the selection and enforcement of one possibility among many’, he also insists that the future is not prescribed, that ‘when society enters a phase of crisis or approaches collapse, we can glimpse the horizon of possibility’.15

British feminism has been partly shaped by liberal ideas of history as a ‘natural’ progression or waves of generational inheritances. Writing in the aftermath of the 1980s HIV/AIDS crisis, queer theorists including Lee Edelman and Elizabeth Freeman have challenged such a teleological view.16 Here too there are resonances with psychoanalysis: the experience of trauma can often shatter understandings of time, as the past reoccurs and repeats in the present.17 New stories about one’s life must be produced for a subject to work through trauma, a process that may also occur during tarot readings.18 Interest in the occult has been a recurring feature across the history of feminism, but the current wave offers speculative possibilities of our contemporary moment.

At a time when the police are using artificial intelligence to ‘predict’ future crimes based solely on past prejudices,19 Powell-Williams’s exhibition insists that there are many different understandings of time. By placing an emphasis on the way apophenia shapes all of us, she challenges the Enlightenment idea that ‘rational’ people have the right to oppress those claimed to be irrational. Rather than subscribe to a top-down model of authoritarian control, as exemplified by Enlightenment narratives of the reasonable versus the ‘primitive’, Powell-Williams centres her subject’s gut knowledge, intuition or alternative beliefs systems. Her argument that apophenia shapes all of us dissolves the division between rationality from irrationality, challenging the logic that we are born either to rule or be ruled. As much as the artist may interpret the tarot cards in her performances, it is the audience who brings their own narrative. Offering a platform for self-knowledge, self-consciousness and self-reflection, The Gates of Apophenia insists on the feminist idea of disobedience, a radical demand, both timely and timeless.

Exhibition details

Candida Powell-Williams: The Gates of Apophenia

Bosse and Baum, London

15th November 2019–25th January 2020

Footnotes

- K. Kelly: ‘Are witches the ultimate feminists?’, The Guardian (5th July 2017), https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jul/05/witches-feminism-books-kristin-j-sollee, accessed 5th July 2017. footnote 1

- H. Farley: A Cultural History of Tarot, London and New York 2009, pp.95–106. footnote 2

- P. Fryer: Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain, London 2018, pp.137–38, 150 and 186; C. Bolt: Victorian Attitudes to Race, Oxford 2010 (first published 1971), p.25; L. Perry Curtis: Apes and Angels: The Irishman in Victorian Caricature, Washington DC 1997, p.18; J. Josephson-Storm: The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences, Chicago 2017, pp.1–5; and S. Freud: Totem and Taboo, London 1919, pp.79, 126, 140, 149, 159 and 162. footnote 3

- O. Davies: A Supernatural War: Magic, Divination, and Faith during the First World War, Oxford 2018, pp.1–9. footnote 4

- Fryer, op. cit. (note 3), p.176. footnote 5

- H. Ellis: Masculinity and Science in Britain, 1831–1918, London 2017, pp.184–86, 188–94 and 198–99. footnote 6

- E. Coomasaru: ‘Magical thinking: Is Brexit an occult phenomenon?’, The Irish Times (18th February 2019), https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/magical-thinking-is-brexit-an-occult-phenomenon-1.3795483, accessed 18th February 2019. footnote 7

- G. Brown: ‘The UK needs a year-long extension on Brexit – to really take back control’, The Guardian, (30th March 2019), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/mar/30/uk-year-extension-brexit-take-back-control, accessed 30th March 2019. footnote 8

- D. Murray: The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity, London 2019, pp.1–2. footnote 9

- D. Tali: ‘The tarot revival thanks to Brexit, Trump and Dior’, BBC News (17th June 2018), https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-44471537, accessed 17th June 2018. footnote 10

- J. Portes and H. Reed: ‘Austerity has hit women, ethnic minorities and the disabled most’, The Guardian (31st July 2014), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jul/31/austerity-women-ethnic-minorities-disabled-tax-welfare, accessed 16th December 2019. footnote 11

- F. Gardner: ‘The unlikely similarities between the far right and IS’, BBC News (30th March 2019), https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-47746271, accessed 16th December 2019; and N. Raha: ‘A poem to banish anger’, in S. Shin and R. Tamás, eds: Spells: 21st-Century Occult Poetry, London 2018, pp.70–73, at p.72. footnote 12

- Farley, op. cit. (note 2), pp.104–05. footnote 13

- C. Massicotte: ‘Psychical transmissions: Freud, Spiritualism and the Occult’, Psychoanalytic Dialogues 24, no.1 (2014), pp.88–102, esp. pp.94–97; and M. Brottman: ‘Psychoanalysis and magic: then and now’, American Imago, 66 no.4 (2009), pp.471–89, at p.474. footnote 14

- F. Berardi: Futurability, London 2017, pp.2, 17 and 28. footnote 15

- L. Edelman: No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Durham, NC, 2004; Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories, Durham, NC, 2010). footnote 16

- K. Noel-Smith: Freud on Time and Timelessness, London 2016, pp.97–132. footnote 17

- J. Mitchell: Mad Men and Medusas: Reclaiming Hysteria, New York 2000, pp.280–82, 288–98, 311 and 314–16. footnote 18

- S. Curtis: ‘Artificial intelligence used by UK police to predict crimes “amplifies human bias”’, Daily Mirror (17th September 2019), https://www.mirror.co.uk/tech/artificial-intelligence-used-uk-police-20078716, accessed 16th December 2019. footnote 19