The shifting spaces of Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s ‘Berlin Files’

by Aneta Trajkoski • November 2023 • Journal article

Introduction

In 2003 a crucial shift occurred in how the Canadian artists Janet Cardiff (b.1957) and George Bures Miller (b.1960) created their multimedia installations. In Berlin Files (2003) they began using ambisonics to create a spatial soundscape comparable to, but sharply contrasted from, the binaural sound of their earlier audio walks, video walks and installations. Whereas binaural audio uses two microphones to record what each ear hears separately and thus creates a three-dimensional sonic sphere that can only be fully realised through headphones, ambisonics is an open field in which the listener perceives a multidirectional sound within their bodily spatial orientation of a room or space. In Berlin Files, ambisonics emulated the intimacy of binaural audio, but rather than relying on headphones, it situated the audience within a shifting sound field across a suite of loudspeakers, which were precisely arranged within the exhibition space.

This article examines the work of Cardiff and Miller made in the 2000s and highlights the significance of new media and spatial practices. It proceeds from the artists’ carefully worded description of Berlin Files as a ‘spatial environment’.1 This term recalls many precedents in art history: Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau (c.1923–37), Lucio Fontana’s merging of painting, sculpture and architecture in his Spatial Environments (1948–68) and Allan Kaprow’s ‘environments’ and concept of ‘total art’, in which he sought to transition the viewer into an active state.2 Following this lineage of emphasising space in installation art, Cardiff and Miller began using the term to stress the physicality of sound in their works. They implemented a new spatial sound and tasked themselves with creating shifts in ‘different types of space’.3 For the artist duo, the spatial capability of sound and how it impacts the viewing experience of the work was the impetus for its creation, as opposed to the more typically discussed cinematic and narrative qualities.

Moreover, the artists’ focus on sound-space amounts to a new formation in the history of sound environments and media. In this article, the present author will underscore the specificity of Cardiff and Miller’s spatial constructions achieved through ambisonic sound and editing. The significance of this framing is imperative because the centrality of media and production in their work presents a renewed understanding of contemporary installation art and the broader sentiment towards experimentation in exhibition practices within contemporary art.

From binaural audio to ambisonics

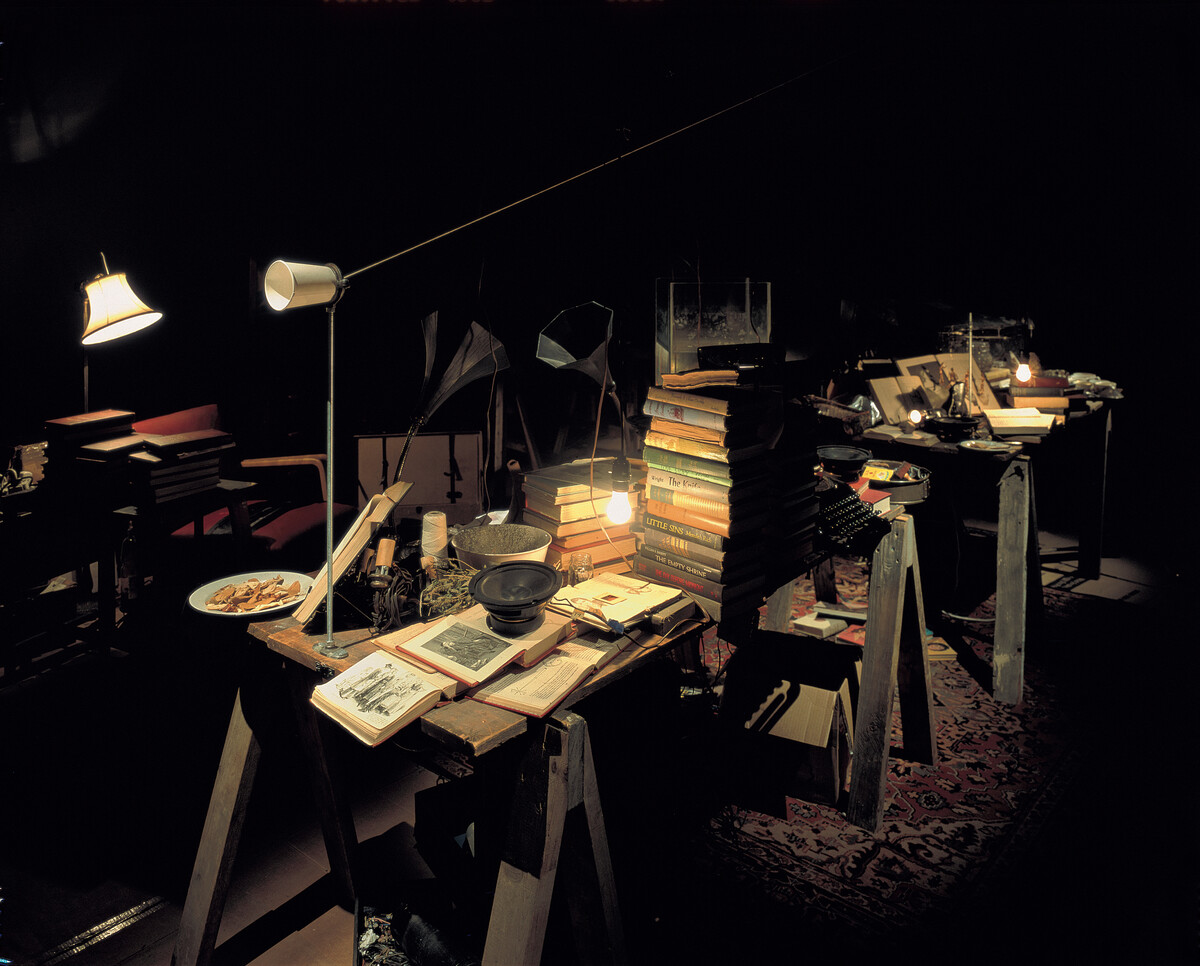

Following their first collaborative work in 1995, The Dark Pool FIG. 1, Cardiff and Miller continued constructing assemblages of found objects, electronics, sensors, cassette tapes, digital audio recordings and binaural sound. The works that followed – The Empty Room (1997) and La Tour (1997) – incorporated binaural sound played through headphones, as did their diorama works Playhouse (1997), The Muriel Lake Incident (1999) and The Paradise Institute (2001). However, it was not until the early 2000s that Cardiff and Miller began to experiment with programming spatialised sound over loudspeaker arrangements within an exhibition space, referring back to the earlier Whispering Room (1991), To Touch (1993) and The Dark Pool.

For Cardiff in particular, the breakthrough work was The Forty Part Motet (A reworking of ‘Spem in Alium’ by Thomas Tallis 1556/1557) FIG. 2, an installation comprising forty black loudspeakers on stands arranged in an elliptical formation.4 The speakers emitted a reworking of Thomas Tallis’s polyphonic motet Spem in alium (Hope in another; c.1570), which was originally written for a chapel that had eight different alcoves, and therefore devised for eight small choirs of five voices each.5 Tallis layered the voices to produce a call-and-response effect and as the combined choirs sang together, waves of sound built and dispersed throughout the chapel.6

In Cardiff’s rendition, she worked with the Salisbury Cathedral Choir, which was split into eight five-part choirs. Each singer was individually wired with a close microphone, and the recorded tracks were then programmed to play through separate speakers. The audience could walk around the arrangement and encounter forty vocal harmonies respectively, or stand in the middle and listen to them all together. Thus, each speaker in the oval formation assumed the guise of a choir member. As Cardiff explained, ‘while listening to a concert you are normally seated in front of the choir, in traditional audience position […] With this piece I want the audience to be able to experience a piece of music from the viewpoint of the singers’.7 Cardiff wanted to ‘climb inside the music’ and isolate each voice to a single channel – an unattainable task through stereo, binaural or two-channel speaker arrangements alone.8 In so doing, the sound of harmonies constructed space ‘in a sculptural way’.9 Isolating the voices enabled Cardiff to produce a spatial effect comparable to the listening experience of the earlier, binaural sound works.

In replicating the spatial effect of binaural sound, Cardiff discovered that the fidelity and quality achieved with 24-bit sound was far greater than binaural recording:

I tried to document it by taking my binaural head […] thinking there would be some way to document this experience. But it sounded like crap. Once you bring in only two speakers, it gets lost. … [It is] about the reverberations and sound waves hitting you from many directions.10

Moreover, the precision required during the editing process proved there was more to the creation of The Forty Part Motet than simply recording the choir and playing it through speakers. Extensive post-production was needed, along with intensive modifications and troubleshooting in order to bring Cardiff’s idea of ‘climbing inside’ the choir to fruition. It was following The Forty Part Motet that Cardiff and Miller first explored ambisonics.11 That same year, they started working on Berlin Files, which opened up a new trajectory in adopting sound as the ‘driving force’.12

Berlin calling

For Cardiff and Miller 2001 marked a dramatic increase in the pace of their career. They gained notable international attention with two key exhibitions: Cardiff’s first major survey show at P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center, New York (now MoMA PS1), and their joint representation of Canada at the 49th Venice Biennale with The Paradise Institute.13 After their inclusion in the biennale, the duo were invited by the curator Jochen Volz to produce an installation for Portikus Gallery, Frankfurt, and they began developing Berlin Files.14 The artists had arrived in Berlin the previous year. Cardiff attended the Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD (Artist-in-Berlin programme) while she and Miller lived in the district of Charlottenburg. Following the residency, the artists split their time between Berlin and Grindrod, Canada. In 1997 Cardiff explained that Germany was appealing because there was ‘a real openness to the idea of the artist. They don’t question a format that’s not in the traditions of what we perceive as art’.15

Once they had moved to Berlin they collaborated with dancers, actors, musicians and composers; they visited the theatre, watched such cult films as Heiner Carow’s Die Legende von Paul und Paula (1973) and researched David Bowie’s time in Berlin.16 The musical icon had moved to the city in 1976, where he shared a flat with Iggy Pop. His move was instigated not only by financial reasons – Berlin was an inexpensive place to live – but also by a desire to escape Los Angeles; he remembered Berlin as ‘a city that’s so easy to “get lost” in – and to “find” oneself too’.17 Indeed, the historian Rory MacLean noted that it was a place where Bowie could remain anonymous: ‘One night, on a whim, he climbed onto a cabaret stage to perform a few Sinatra songs. The local audience, with their infamous terseness, shrugged and asked him to step down’.18

Just as the city was the muse for Cardiff and Miller’s Berlin Files, its sense of reinvention and rebuilding also saturated the artists’ time there. The work presented a stripped-back void, a far cry from the bricolage of their earlier works, such as The Dark Pool. The installation was simply constructed: speakers, a small projection screen, plywood walls, fabric baffles and wooden bench seating. It was a pivotal work for the duo: advancements in sound technology – in this case, the availability of ambisonics – transformed how they used sound; and it also signalled a turn in how they realised their co-authored installations.

More like spatial environments

Cardiff and Miller often cited the audience’s physical experience of sound as the impetus for their works. Although it was typically assumed that narrative was the catalyst, Cardiff in particular stressed physical and spatial characteristics: ‘One of the main things about my work is the physical aspect of the sound […] A lot of people think it’s the narrative quality, but it’s much more about how our bodies are affected by sound. That’s really the driving force’.19 Nonetheless, literature on Berlin Files and their other works have tended to focus on the storyline and cinematic qualities. A description published by the Phoenix Art Museum on the occasion of the group exhibition Constructing New Berlin is typical of this type of discussion:

The film noir nature of the city inspired elements of the illusory and stunning video installation Berlin Files by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller. A non-linear film montage with surround sound, the piece has been acclaimed for its emotional range and abstract beauty.20

In such efforts to prioritise sight, what was overlooked was in fact the crux of Cardiff and Miller’s installations from this point onwards: the development of spatial sound and its conceptual implications.

Interestingly, this oversight was not symptomatic of an unfamiliarity with Cardiff and Miller’s work. Instead, it was indicative of the conventional narratives adopted in discussions of sound and video presentations, in which sound was subordinate to the image. For example, the scholars Anamarija Batista and Carina Lesky rely on film theory to describe how Cardiff used sound and space in Her Long Black Hair FIG. 3, a forty-six-minute audio walk through Central Park, New York.21 Armed with headphones, a Sony Discman, a packet of photographs and a map, the walker retraces the footsteps of a dark-haired woman.22

Similarly, Carolyn Christov-Barkergiev often described the ‘filmic’ qualities of the duo’s works and their associations to collective memory or fictive narratives.23 Moreover, in an interview with Cardiff and Miller for their Whitechapel exhibition in 2003, the curator Andrea Tarsia referred to Berlin Files as a ‘film’ symbolised by its ‘in-betweenness’ and ‘disjointed’ character. The work, Tarsia observed, ‘flickers between light and darkness, between image and its absence. There’s a feeling of drifting in and out of consciousness, and the series of scenes that make up the film share the disjointed quality of dreams’.24 He proceeds to ask Cardiff: ‘are these notions important to you?’.25 In response, Cardiff explained that their works were not films in the conventional sense: ‘I would hesitate to call them films […] more like spatial environments’.26

It is necessary to clarify what Cardiff meant by ‘spatial environments’, and it must be emphasised that her correction was not an objection to Tarsia’s observations. Cardiff and Miller’s works of art often suggest dream narratives, the flow of consciousness, memory and states of ‘in-betweenness’. However, to rely on such familiar observations would be to reify the most obvious conclusions about their œuvre. Instead, if one probes Cardiff’s characterisation of the ‘spatial environment’, attention shifts to a far more pertinent aspect of the production of such works: their formation.

The break: substituting the cinema situation for spatial environments

One can understand the significance of Cardiff and Miller’s spatial environments by determining how Berlin Files differed from their earlier installations. Initially, however, the path to understanding their works in this context becomes more convoluted, as many employ tropes from the entertainment industry and stagecraft.27 Therefore it would be natural to assume that their installations are about cinema and literature. Furthermore, comparable works, such as The Muriel Lake Incident and The Paradise Institute, adopted these filmic and literary devices and mimicked the conditions of cinema viewing, or what Roland Barthes called the ‘cinema situation’.28

In the mid-1990s and early 2000s Cardiff and Miller created a series of dioramas that replicated early twentieth-century cinema architecture, which were reminiscent of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s series of black-and-white long-exposure photographs Theatres (1978–ongoing). What made the diorama works unique is that they simulated the experience and architecture of a theatre space. For example, The Muriel Lake Incident FIG. 4 is a miniaturised movie theatre constructed from plywood. Up to three people can stand outside the structure and peer through a window to watch a video screen while listening to the binaural soundtrack through headphones. The inside of the structure was fitted with red curtains, a screen and a fan-shaped amphitheatre FIG. 5.

By contrast, The Paradise Institute FIG. 6 is a diorama large enough for visitors to enter. The exterior resembles a freestanding packing crate, while the inside is soundproofed, air-conditioned and fitted with plush, red theatre seating and a burgundy carpet. At the front of the space is a seemingly distant cinema screen, installed inside a miniaturised model of a cinema theatre with tiered seats. Here, the ‘blinding white nothing’ of the screen in Sugimoto’s photographs is replaced with a film-noir-esque sequence of scenes as the binaural soundtrack plays through headphones FIG. 7.29

The Paradise Institute presented visitors with the illusion of a cinema experience.30 When it was shown at the Venice Biennale, visitors collected a ticket and formed a queue outside the structure. Upon entry, they were instructed to sit on the velour seats, put on a pair of headphones and wait for the ‘film’ to begin. While seated, a soundtrack of imaginary patrons entering the room, chatting, rustling packets of snacks and clearing their throats was played in binaural sound. At the same time, Cardiff’s voice whispered in the visitor’s right ear, asking if they had turned off the stove. As Cardiff explained, ‘we wanted to do a three-dimensional version of how people see movies. You’re physically here, but you’re also in the movie, and then the movie comes in and mixes with your thoughts about, “Oh, did I leave the stove on?”’.31 Once the ‘film’ started, a sequence of abstract scenes played over the audio and video – a house burning, a cabaret singer, a woman running, a hospital scene FIG. 8 – and when it finished the visitors were asked to exit. The structure and video sequence design produced what Miller called a ‘cinema situation’,32 a reference to an essay by Barthes from 1975, in which he wrote: ‘The texture of the sound, the hall, the darkness, the obscure mass of the other bodies, the rays of light, entering the theater, leaving the hall […] I complicate a “relation” by a “situation”’.33 This condition was provoked by more than what was playing on the screen.

In cinema the purpose of sound is to enhance the viewer’s absorption in the film. What was at stake in The Paradise Institute was not only the activity happening on screen or the sound’s enhancement of the filmic experience but rather the total environment of the installation – including the institutional structures, conditions of the audience and viewing behaviours.34 ‘When you enter you should feel this kind of disjunction between moving away from a gallery space or a museum space to something other than that’, Miller explained.35 Cardiff and Miller used binaural sound to accentuate these conditions.

Consequently, The Paradise Institute simultaneously interrogated and articulated the total space of the installation. Hans Belting referred to this space as the room that we ‘usually occupy with our bodies, but which we tend to forget while travelling with our imagination to the sites we are shown in the movie’.36 However, in The Paradise Institute the binaural sound did not enhance the viewer’s absorption in the ‘film’ but instead made them more aware of their physical and spatial presence as they sat in the diorama theatre. The binaural sound denied them a conventional cinema experience as their attention was directed towards the entire installation and their experience of real and recorded sounds – of people whispering and rustling in their seats, a mobile phone ringing and prompts about turning off the stove. Miller explained that they sought to baffle the viewer ‘in a way that for at least a moment they are unsure of what is real and what is fiction. In that piece the actual film isn’t as important’.37 This momentary confusion, what Andrew Uroskie has referred to as a ‘double consciousness’, collapsed the boundary between the binaural recording and the physical experience.38 As the two spaces merged, what became crucial, as Miller points out, was the fleeting, yet powerful, moment of confusion.

By contrast, Berlin Files marked a break from Cardiff and Miller’s reliance on the cinema experience in their works of art. Berlin Files was ‘the first time that the “film” exists on its own outside of the cinema situation, which both The Paradise Institute and The Muriel Lake Incident use’.39 Rather than borrowing from the conventions of cinema, they envisioned their spatial environment through different circumstances. Berlin Files substituted binaural sound for ambisonic sound and utilised the gallery’s architecture and the editing of the audiovisuals to create its spatial environment. Loudspeakers replaced headphones. Although The Paradise Institute simulated a movie theatre, the headphones confined the experience of the three-dimensional sound to the listener’s head. In Berlin Files, the amplification of sound via loudspeakers implicated the listener’s body within the physical space of the installation – this is what Cardiff referred to as the ‘physicality of sound’. Rather than a regular stereo system that produces a blanket or wall of sound with slight spatial variation, the artists designed a twelve-channel speaker arrangement that reproduced sound as the human ear would hear it. Therefore, the spatial dimension of the sound implicated the listener’s body within the gallery’s physical space. The cinema situation was substituted with the spatial environment as the highly spatialised soundscape negated any predisposition for the visitor to lose oneself in the experience.

The architecture, editing and sound composition

The sound system was presented within a custom-built structure for Portikus, Frankfurt FIG. 9. The dodecahedron structure was six meters wide, designed to maximise the spatialisation of the twelve-speaker system. Each speaker was embedded within a felt-covered wall panel, and a single projection video screen measuring 82 by 150 centimetres was installed on one wall. Unlike the typically large cinema screen used in commercial theatres, the one in Berlin Files was modest and restricted by the narrow width of the plywood panels. The curator, Volz, also observed that the screen was ‘very small compared to the [size of the] piece’, suggesting that the video was only part of the equation.40 Instead, the detail and effort assigned to the design of the room, the positioning of the speakers and the size of the screen indicated that there was more at stake than recreating a cinema experience. The final twelve-sided structure was devised after Miller sketched many drafts in his notebooks, testing the feasibility of various panel dimensions and combinations. The speakers were positioned at multiple heights and angled to project sound towards the centre to produce a spatialised effect.

Berlin Files is a thirteen-minute sound and video composition, comprising five short scenes shot across various locations in Berlin and Canada. The audiovisuals were edited to evoke a ‘similar experience to leafing through a filing cabinet, shifting from one file to another’.41 In the lead-up to the closing scene, the following sequence played out: a woman crosses a street at night; a car drives through a snow-covered Canadian field; a camera pans through an apartment in which a person plays the piano FIG. 10; and a blonde woman walks down an empty U-Bahn corridor at night, the scene turned upside down FIG. 11. What connected these scenes were in fact absences: long pauses as one piece of footage transitioned to the next. These blank-screen moments were synced to coincide with unrelated sounds, such as an orchestral composition, a helicopter or a train passing overhead. The recording played out in ‘incredibly precise multichannel sound’ as it resonated across the speakers.42

The two-minute closing scene begins with Cardiff’s whispered voice singing the opening lines of David Bowie’s ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide’ (1972). As she sings, a blank screen fades into a scene inside the White Trash Fast Food bar in Berlin FIG. 12. A karaoke singer, played by the Berlin-based performance artist John Jones, stands by the bar in a glistening silver blazer, microphone in hand, singing the chorus of the Bowie classic to an empty bar. As the camera pans through the adjacent rooms, distinct variations and contrasts in the sound – its texture, direction, volume, distance and spatial qualities – emerge. The aural experience of the soundscape shifts from the impression of being in the bar and hearing the performance through the loudspeakers to hearing the performance from the room next door. In this scene, rather than using sound as cinematic support, the soundscape leads the piece.

Sound as protagonist derailed the established notions of the audiovisual that emerged out of cinema discourse, which has traditionally downplayed the significance of sound. Gilles Deleuze, for example, considered sound and image as being embedded within film, and Michel Chion considered sound not as subordinate or in juxtaposition to the image but in ‘synchresis’ to it.43 In both of these accounts, sound reinforced the visual rather than being dominant. Cardiff explained that when the visuals were ‘enhanced by big sound’, the audience was transported into a virtual world.44 The space evoked by the cinema experience is what Hollis Frampton described as the ‘null space’ in which the body of the cinema-goer is suspended.45 This space became the default of what Noam Elcott called the ‘artificial cinematic darkness’, where all but the luminous screen was obscured from view.46

However, unlike these examples, the task of sound in Berlin Files was not to enhance the video edit or teleport the audience into a virtual world. Instead, sound was the driver: variations and contrasts were precisely edited to form a specific spatial environment. Cardiff described this process: ‘When you edit to a new scene, you are shifted into a different type of space’.47 These varying spaces are formed by the intersecting sounds and blank screen passages as they transition from one soundscape to the next. Cardiff and Miller’s editing – the manipulation and formation of spatial sound – is central to the work’s success. Yet it is derived from not only their ability to create a plausible soundscape, but also the way the works reveal their artifice – a device that is apparent in Berlin Files.

Shifting spaces

Miller explained that using spatial sound to transition Berlin Files from scene to scene created ‘a scenario where we try to suspend your disbelief so that you’re within the reality of our piece, and then somehow we will pull the rug out from under you by saying something or having a sound that destroys that reality’.48 This effect goes hand-in-hand with the moment of confusion between the binaural soundscape and reality described earlier, as a dual effect. In a 2013 interview with the artists, David Blazer noted that Cardiff and Miller’s works often draw attention to viewership, intensifying ‘mystification rather than a demystification’.49 Indeed, as Cardiff asserts, ‘usually there’s some point at which we show the technology’.50 The artists agreed that the extent of this reveal differs depending on the work.

For example, Storm Room FIG. 13 is a work set up much like The Paradise Institute: a self-contained plywood structure in which the objects of technology – a large Apple computer, cables, lights, water pipes, packing crates, amplifiers and speakers – are visible from the outside. Upon entering the darkened gallery space, the viewer is led around the outside of the structure, able to observe the wires and workings. Inside, the space is revealed to be a replica of a traditional home in Tōkamachi, Japan. A simulation of a thunderstorm plays out and water leaks through the ceiling and gushes across the windows. In relation to The Forty Part Motet, Cardiff stated that she chose not to hide the speakers and cables because people see them as ‘invisible anyway’.51 However, it would be implausible to deny the sculptural quality as it is so explicit. Rather, what Cardiff’s statement suggests is that by situating technology in plain view, the audience cannot be consumed by the illusion of the spatial sound as its artifice, or inner workings, are laid bare. This differed significantly in Berlin Files, as the speakers were embedded into the walls of the structure. For the visitor situated at the centre of the work, the darkness of the space and the presence of the screen conjures certain viewing behaviours, such as those expected in a gallery space or cinema. However, before the visitor can become consumed by the experience, they are presented with the unfamiliar sensation of hearing highly spatial, realistic recorded sound.

Cardiff and Miller used continuity devices to suggest that there was a narrative to be followed in Berlin Files, in both video and audio, such as their voices in the studio or the reappearance of the blonde woman. This is a strategy that has been consistently present in their practice. In their audio walks, for example, the narrative and directions are a device to instigate people to walk from one place to another. Such ploys satisfy the habitual behaviours of the audience by luring them into the act of constructing a plot. Berlin Files was also composed with these psychological manoeuvres in mind. Although their use should not dominate the discussion of Berlin Files, it is crucial to acknowledge their role in capturing the viewer’s attention, so that they could experience what is really at stake in the installations: the development and experience of the spatial environments, or as Cardiff described, the physical quality of sound.

In place of a structured plot, Cardiff explained that they used sound to ‘pull’ and ‘shift’ space to progress the scenes. In this way, the spatial environment of the work of art becomes an expanded physical encounter:

Our bodies respond immediately when the room becomes dark and there is just a voice or sound. Because of this we can work with the narrative in a different way than a regular film because rather than story structure we can concentrate on the different type of space being pulled and shifted.52

Instead of a linear storyline, the sound set the pace for the piece’s unfolding. The blank passages, in which the audience hears audio exclusive of supporting visuals, functioned as transitionary junctures between the composed scenes. Hence, the sound played out around the audience spatially, sculpting movement and variation in the acoustic space. The linear progression usually afforded by a narrative plot was substituted with spatial shifts in the sound perceived, emphasising its direction, fidelity, loudness and texture. The artists ensured sufficient contrast between what Cardiff called ‘darkness’ and ‘lightness’ of sound.

Experiencing recorded spatial sound is, for the most part, unfamiliar to most individuals, but we are accustomed to hearing ‘real’ sounds spatially. Initiating an unaccustomed experience within the confined structure of a gallery space, Cardiff and Miller used ambisonics in Berlin Files to mobilise sound and construct space. The piece plays out around the audience, sculpting movement and variation as the sound transitions from one acoustic space to another. Stripped of the objects, kinetics and theatrics present in their previous works, Berlin Files is an act of restraint on Cardiff and Miller’s part.

The austerity of the works of art that Cardiff and Miller produced in Berlin in the 2000s echoed what had emerged in Bowie’s music almost twenty years before. MacLean noted that Bowie ‘realised that his goal was not simply to find a new way of making music’ but to ‘reinvent – or to come back to – himself. He no longer needed to assume character guises to sing his songs. He found the courage to throw away the props, costumes and stage sets’.53 Bowie traded traditional rock riffs and alter egos for the stripped-back ambient tones of the so-called Berlin Trilogy albums: Low and Heroes (both 1977) and Lodger (1979).

Similarly, Berlin Files also signified a new simplicity that Cardiff and Miller pursued in their ‘speaker works’.54 In the closing scene of Berlin Files, the cabaret singer stands alone at the bar, microphone in hand, belting out Bowie’s ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide’. He sings along unnoticed by his fellow punters: the isolated blonde woman on the phone, the barman and the group chatting in the adjacent room. However, the surround sound that resonates through the twelve-sided structure implies that sound alone could be more compelling than the ‘props, stage sets, and gimmicks’ of the works that had defined Cardiff and Miller since the mid-1990s. The artists reacquainted themselves with the restraint and confidence to allow sound to define the spatial environments in their work and narrative drive as it did in their earlier pieces. Adopting new technology, compositional techniques and ambisonics allowed them to expand their experimentation of spatial sound beyond what they could realise previously.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the artists, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, and Jochen Volz for their time and generosity.