Proposals of critique: Maria Eichhorn’s ‘Building as Unowned Property’ (2017–)

by Adela Kim • June 2022

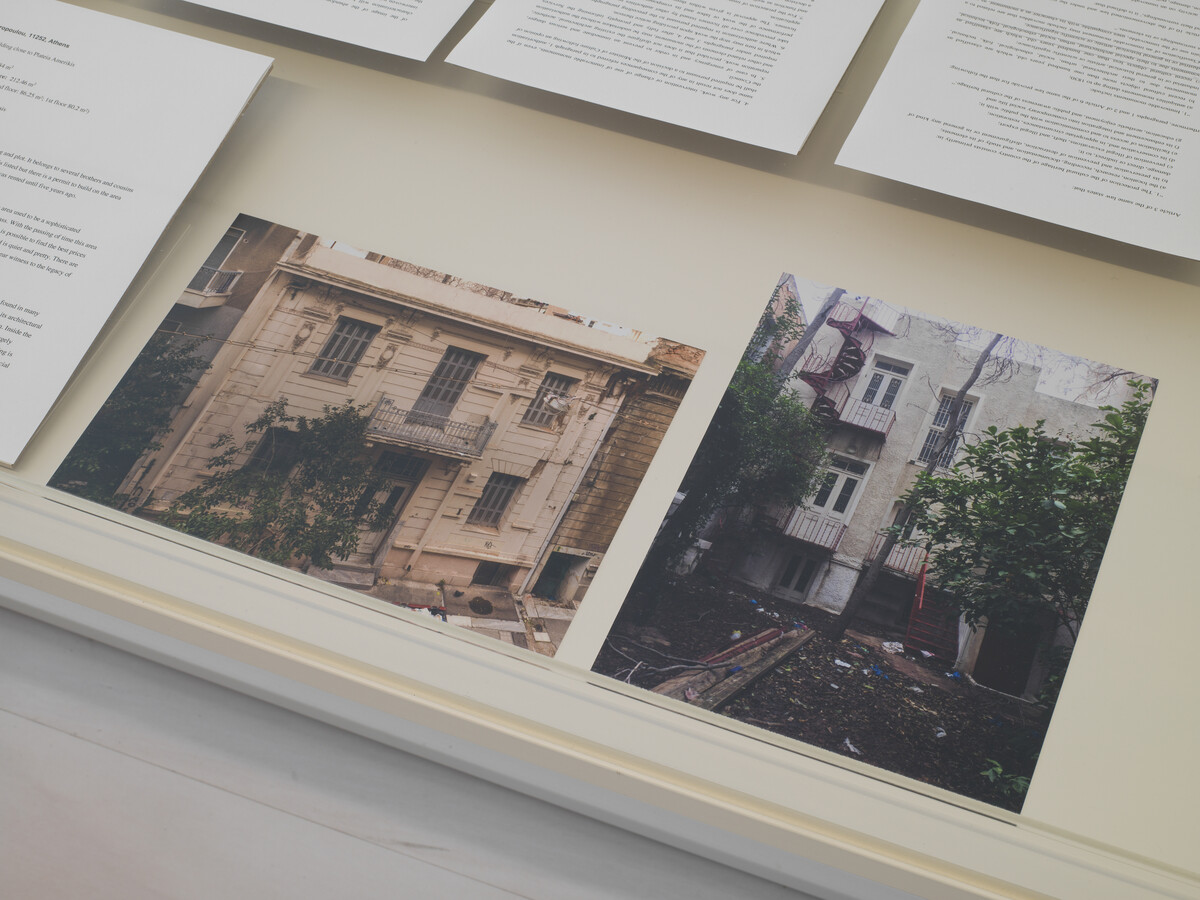

On 8th April 2017 the Neo-classical building on 15 Stavropoulou, Athens, looked the same as it had done for the past five years, apart from the peeling paint on the façade. However, on this day the typically quiet street in the neighbourhood of Plateia Amerikis was crowded with people. The tourists that usually storm the Parthenon were there, armed with belt bags and sunglasses, zooming in and out of Google Maps with their fingertips to ensure that they were, indeed, at the right location. Soon enough, they discovered the affirmative signs: a small QR code and a plate in English, German and Greek, which declared that the building was ‘designated for public use, to be legally converted into a property that de facto does not belong to anyone’. The plaque further asserted that the building challenged ‘fixed notions of public and private property’. Some visitors perhaps tugged at the door out of curiosity, wanting to see what awaited inside. The property, however, remained shut.

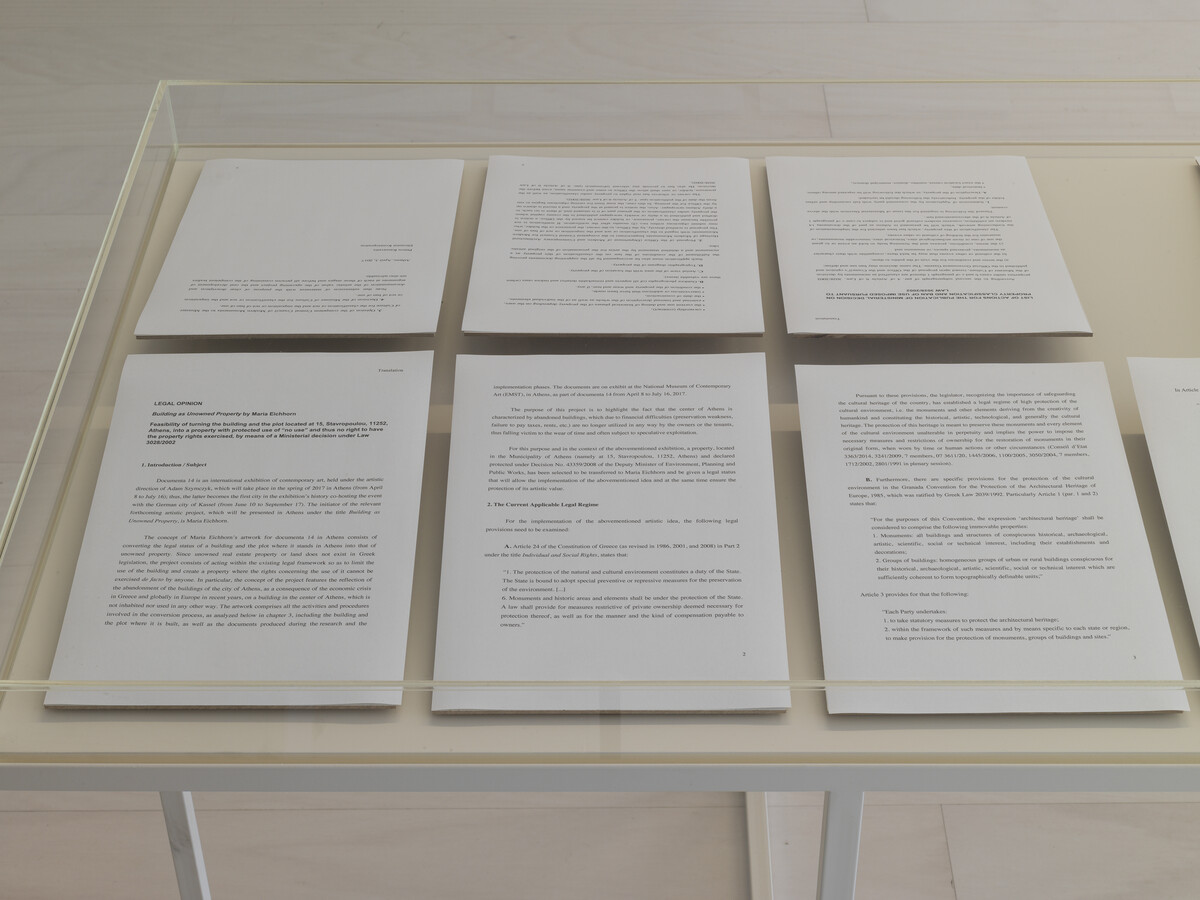

The scene described centres around Building as Unowned Property FIG. 1 FIG. 2, a project by the German artist Maria Eichhorn (b.1962) for documenta 14 in Athens in 2017.1 Conceived in response to the economic crisis in Greece, and the subsequent abandonment of buildings by those who could not afford to pay property taxes, the work sought to resist real estate speculation by converting the legal status of an owned building to ‘unowned’. In so doing, the work intended to provide a respite from the merciless logic of neoliberalism that had forced people to leave their homes. Since the status of ‘unowned’ does not exist in Greek law, Eichhorn’s initial proposal did not specify the exact framework through which she would accomplish this task. As the project progressed, a solution eventually emerged: the application for cultural heritage protection. These preparatory documents and the proposals, if the visitors wished to learn more, were shown at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens FIG. 3.

The display of the property alongside supplementary papers hews closely to Eichhorn’s earlier work, and that of many artists engaged with institutional critique. At the heart of Eichhorn’s practice is how concepts of ownership and property, which have fundamentally forged the circulation of capital, might be ‘undermined’ through bureaucratic systems meant to enforce the status quo.2 Eichhorn’s Acquisition of a plot, Tibusstraße, corner of Breul, communal district of Münster, plot 5 FIG. 4, for instance, entailed transferring back the land she had acquired into municipal ownership in Münster. As with her earlier works, the critical reception of Building as Unowned Property has focused on the administrative aspects of Eichhorn’s intervention. For example, in Alexander Alberro’s entry on the documenta 14 website he argues that Eichhorn’s art ‘transforms its operating logic from within, seeking to enact permanent structural change’.3 Writing in Artforum, Polly Staple emphasised similar aspects, stating that the work utilises ‘the components of the administrative everyday in radical and counterintuitive ways [… to] reveal and trouble systems of value and redirect flows of power and capital’.4 Only recently have such scholars as Kelley Tialiou begun to assess the nuances of the work, taking into consideration the ‘condition of urban ruination’ and documenta 14’s titular premise of Learning from Athens, among others.5 Yet still missing from the discussion is the significance of abandoned buildings as an alternative form of housing to those without a roof; the onerous cultural protection laws and the widespread failure of the Greek government to enforce such measures; and the patrimony entailed in a German artist dictating to the Greek authorities what to treat as cultural property. Most crucially, almost no one has acknowledged the fact that Eichhorn failed to acquire the initial property on 15 Stavropoulou and convert its status.

Focusing on the rupture between the proposed and the actual work of art, as well as the different temporalities at play, the present article will consider how Building as Unowned Property – far from simply detouring property law – tracks the fraught history of German-Greek relations, from Germany’s ideologically driven conception of Neo-classicism in the nineteenth century to the austerity programme of 2008. At the same time, the fact that the contours of the proposal have continued to morph, and that the initial supplementary documents have continued to be exhibited without an associated property, raises crucial questions about what Building as Unowned Property enacts. At stake is how the work – as a simultaneously unfolding proposal and actualised work at 15 Stavropoulou – might pave the way to a new form of critical mimesis and self-reflexivity within institutional critique. Through its various temporal disjunctures, the work both stages and interrogates the potential for supposedly critical works of art to levy symbolic violence.

Learning from Athens sought to foreground the ‘Greek Crisis’ as ‘an opportunity to open up a space of imagination, thinking, and action, instead of following the disempowering neoliberal set up that offers itself as (non)action implied in the (non)choice of austerity’.6 Yet this ambitious premise was soon overshadowed by grave blunders: Greek employees were misled over their wage and working conditions and interns were asked to scurry bags of cash to Athens, as the organisers did not anticipate the need to pay Greek suppliers in cash and there was a cash withdrawal limit of €120. Despite these logistical mishaps, at a press conference, the CEO of documenta deemed the exhibition a ‘gift’ to Athens.7 Soon, accusations against documenta 14 abounded, ranging from critics condemning it for harbouring ‘colonial attitudes’ to the former finance minister of Greece decrying the exhibition as ‘crisis tourism’.8

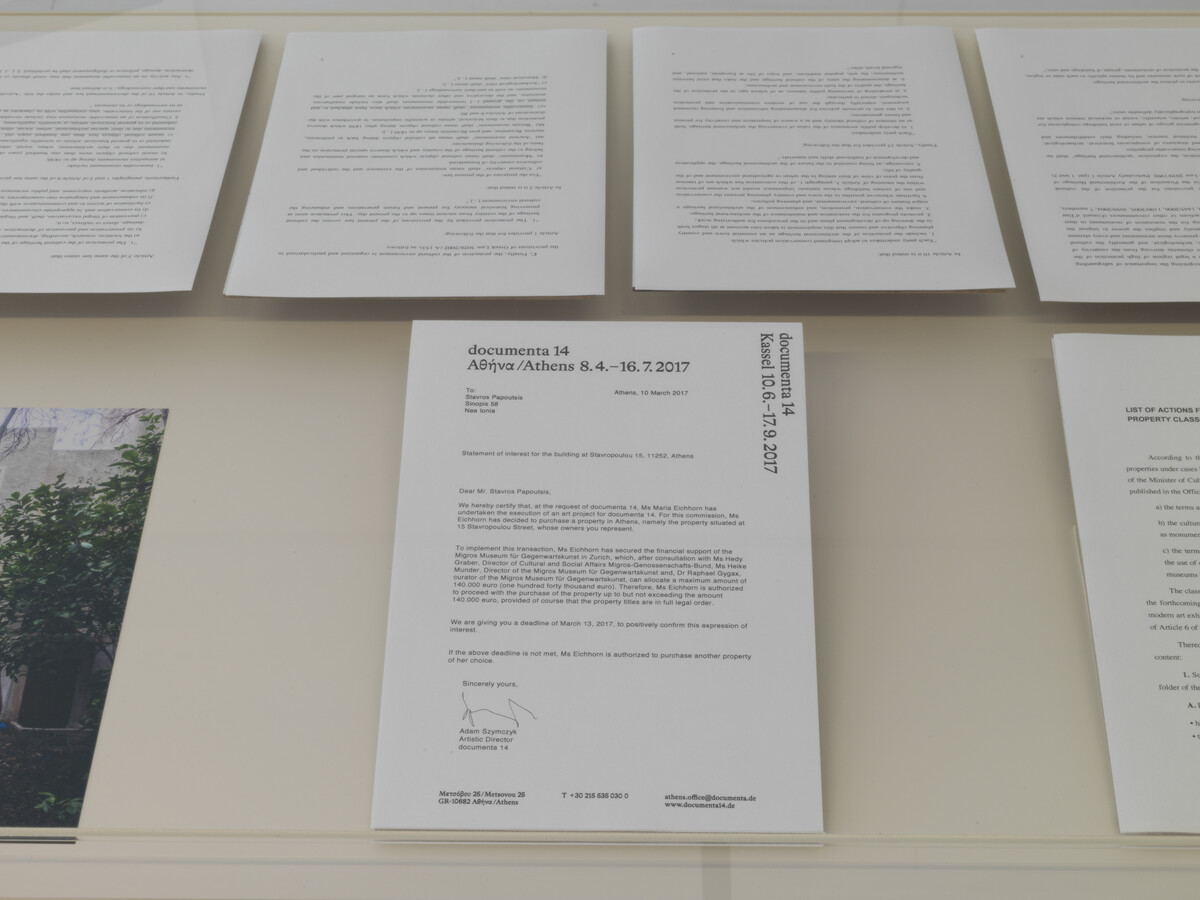

Notwithstanding the attendant issues, documenta 14’s ethical commitments to examine the conditions of the Greek debt crisis and build a north-south solidarity are echoed in the supplementary documents for Building as Unowned Property, which include the project proposal FIG. 5, legal opinions and a letter from the director of documenta 14, Adam Szymcyzk FIG. 6. The proposal begins with a description of the urban space of Athens. Declaring that Greece has plunged into ‘social, economic and political chaos’, Eichhorn notes forebodingly: ‘Buildings are given up by their owners because they can no longer pay the increased property tax, tenants can no longer pay the rent […] The houses are left to their own devices and left to decay’. Here, there is no indication that Eichhorn was set on converting the building into a protected cultural property. Instead, she sketches out an undefined and delegated process, in which ‘the transfer of the building to an unowned status may be carried out directly by the original owner or by an intermediary’. The building, too, had not yet been chosen when the proposal was written, although the specifications reveal that Eichhorn was searching for an already abandoned property. She writes: ‘Which buildings were abandoned by the owners? For what reason? Which are offered for sale?’ There were logistical concerns to take on board as well: the text specified that the building ‘be located in the centre of Athens as close as possible to documenta and event venues’, and that it be in a ‘good structural condition’. Lastly, Eichhorn asks if the building could be ‘donated by the owner to documenta / artist’, perhaps not wanting to become a real estate speculator herself.9 The questions posed in the proposal reveal the ambiguities that artists who participate in the global circuits of the art world navigate – a phenomenon first discussed by George Yúdice in 2003, but one that continues to be germane today.10 Yúdice notes that among the conflicting agendas that artists must confront are the vectors of resources: that is, although critics have portrayed Eichhorn’s project as a service to the city of Athens, one might also discern the way that the Greek national housing crisis serves as a resource and as material for Eichhorn, even if the project were to thwart the economic mechanisms driven by structural inequality.

The property that Eichhorn ultimately engaged with for documenta 14 was a two-storey building from 1928. Provided by Eichhorn as a part of the work, a document entitled ‘15, Stavropoulou, 11252, Athens’ furnishes mundane details of the building at the said address, using standard real-estate advertising language to describe the location and architecture. The document boasts that the property belongs to ‘several brothers and cousins’, a form of multiple ownership that is common in Greece; that the neighbourhood Plateia Amerikis offers ‘the best prices for value’; and the ‘very sophisticated Neo-classical buildings nearby’ attest ‘to the legacy of wealth’.11 Importantly, we learn that the building at 15 Stavropoulou, too, is in the Neo-classical revival style, maintaining the possibility that its value will rise in line with neighbouring buildings.

Yet there are conspicuous omissions in the liberal adumbration of details. Eichhorn neglects to mention that the building’s Neo-classical architecture recalls the period when Greece was ruled by the Bavarian Prince Otto Friedrich Ludwig (1815–67), who became known as King Otto. He was established as the new ruler of Greece through the London Conference of 1832, which was convened by Britain, France and Russia – the three superpowers that had aided Greece in gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire, only to subsequently impose their choice of monarch. Barely an adult at the time, King Otto moved the capital of Greece from the coastal city Nafplio to Athens for the sake of its history; he envisioned it as a city that would venerate the tradition of Classicism. This was in line with the emergence of the study of Antiquity from the eighteenth century, heralded by such figures as Johann Joachim Winckelmann.12 To this end, he enforced a systematic programme of erecting Neo-classical buildings throughout Athens with help from German architects, imposing a German-inflected visual account of Greece’s past. This regime continued well into the early twentieth century, only to be taken over by the Nazis, who – in conjunction with Italy and Bulgaria – ushered in an era of terror, widespread poverty and destruction of infrastructure, even as Adolf Hitler extolled Greece as ‘a place where all that we today called human culture found its beginning’.13 Following the Second World War and the Greek Civil War (1943–49), and under the pressures of continued financial hardship, a system of antiparochi emerged, in which a contractor would approach the owner of a house or a plot and offer to build apartments with numerous units.14 Despite having incentivised such a system by little to no tax for the land owner, the Greek government has since sought to rein in the resulting urban growth and dereliction of cultural heritage. In 1975, it first inscribed the protection of cultural heritage into its constitution and, three decades later, in 2006, it imposed a system of property tax on the antiparochi. The remaining Neo-classical buildings have become ‘architectural gems that must be supported’, as one culture ministry official attested.15

With this historical excursus, we can return to the proposal of Building as Unowned Property. Since there is no official legal mechanism to declare a property as ‘unowned’, the process that Eichhorn ultimately considered as approximate to this condition was to declare it as a cultural monument.16 ‘Legal Opinion’ FIG. 7, a document written by two Greek lawyers, Petro Kassavetis and Frossini Koutsopoulou, proffers a notably circular rationale for the building’s cultural significance. The lawyers note that the work holds a ‘historical significance for being included in documenta 14 and for the imprint in the collective consciousness and memory of the image of the abandoned property in the center of Athens’.17 Put another way, although the building needed to be turned into cultural property as a part of the work, the building could only become cultural property because of the work and its inclusion in documenta 14. Far beyond a logical fallacy, the outlined process of converting the building into cultural property speaks to a temporal organisation central to forms of neo-colonialism today. Doreen Massey’s astute observation regarding modernity’s tendency to convene ‘coexisting spatial heterogeneity’ into a singular temporal plane proves useful here.18 Underscoring how the conceptualisation of space and time construct a form of power and knowledge, Massey notes that compressing ‘different stages in a single temporal development’ results in the persistence of colonial rule by pitting the developed world against those excluded from the engine of neoliberal globalisation.19 Building as Unowned Property promises to enact this spatio-temporal organisation by purchasing the property and dictating the terms of a country’s cultural memories. As Germany and the rest of the Eurozone moves onwards, Greece is to remember this period of economic crisis through this building – all as prescribed by a German artist.

To be clear, this spatial convening of time is also accompanied by a form of temporal erasure, as the historical context of the Neo-classical architectural style in Greece is unacknowledged. We may also recall Massey’s diagnosis of the current globalised world as living in ‘an imagination of instantaneity’, whereby ‘time becomes impossible’.20 Eichhorn’s work ushers its own form of instantaneity, whereby the long history of the German imposition of a cultural memory in Greece is evacuated and makes its own engagement appear as a new and immediate idea. History might be repeating itself, but the past is forgotten; all that remains is the contemporary and the attempt at its historicisation. In a legal sleight of hand and some circular rhetoric, the building’s inclusion in documenta 14 becomes the only source of cultural significance.

Contiguous to this temporal erasure in Eichhorn’s work is the recent drive to actively disinherit familial wealth in Greece, underscoring issues of agency and the disparate conditions of temporality. For many younger Greeks, the expungement of cultural memory and history is involuntary. Whereas property inheritance in Greece was once deeply coveted due to the associations with ‘lineage, national belonging, and cultural roots’, the European Union austerity programme, in conjunction with stringent cultural heritage protection laws, have made the prospect of an inheritance much less desirable for many Greeks.21 Although property ownership is bound up with national pride and the ‘duty to wider collectivities of family, neighborhood, and nation’,22 in the face of economic pressures, increasing taxes and the mandatory fees associated with properties of historical importance, many working-class Greeks have had to relinquish their properties so severing the connection with their family history. As cited in a recent anthropological study, this quote from a Greek national, known only by his first name Giannis, cuts across the power dynamics hidden in the blitz of instant time:

When they drain you of your past, your legacy, your lineage by making it impossible to inherit, how do they expect you to build a future for your family, your nation? You are removed from everything that is meaningful. In the end you want to be removed and actively seek disconnection […] That is what we are doing now, trying to get away from the global and national processes.23

Compare Giannis’ pleas with the rationale put forth by Eichhorn’s legal documents, drawn up by the lawyers after the building at 15 Stavropoulou was found: ‘[the conversion is] also a guarantee for the recognition of the property as a recent cultural object in need of protection by the Greek state so that its artistic value can be preserved in historical memory’. The disparities in agency in relation to cultural memory is conjured up and dramatised by the proposal.

Further down in ‘Legal Opinion’, the proposed conversion of the building to a cultural monument morphs into a discussion on the technicalities behind use and ownership. The lawyers note that as a cultural monument, the building would now be under ‘prohibition of any kind of use (except for the uses defined pursuant to a decision of the Minister of Culture issued in accordance with Article 46 par. 1 of L. 3028/2002 following an application)’.24 According to the law, the state could dictate the way the property could be used in many capacities, ranging from public visits to cultural events. Not mentioned is that the 2002 law cited above underscores that the property at 15 Stavropoulou would be owned by the state as a cultural monument, rather than being ‘unowned’, as the title of the work suggests. In Acquisition of a plot, Tibusstraße, corner of Breul, communal distrct of Münster, plot 5, Eichhorn exploited a similar mechanism of returning the property to the state to ruminate on broader concepts of ownership. In discussing this earlier work, Eichhorn stated in an interview from 2017: ‘One consideration was whether it was possible to detach the ownership of an item from that same item without disposing of or destroying it, so that it belonged to nobody, or even better, it belonged to everybody’.25

In Building as Unowned Property, the concepts of nobody and everybody evoke debates on culture and property ownership. As touched upon earlier, Greece instituted a new policy on the protection of cultural heritage in 1975 as a way to limit excessive urban growth and encourage sustainable development.26 Yet in recent years, culture has become a hasty stopgap measure enacted by the government to obscure the failed promises of neoliberal globalisation. Take, for instance, a 2014 Reuters article on decrepit properties in Athens. Written well after planning for documenta 14 had begun, it focuses on an abandoned apartment complex located a mere nine-minute drive from the building on Stavropoulou. The reporter notes that the state had purchased the building in 2001, hoping to demolish it and develop a new property in cooperation with the private sector. But in 2008 when austerity measures struck and both the state and corporations were bankrupt, the state chose to declare the complex a ‘heritage site worthy of protection’.27 In actuality, the building remains deserted, unused by the state. As such, the cultural sector serves as grounds for delays in addressing the consequences of the economic crisis.

Against the backdrop of the Greek government using cultural protection law as a provisional fix, a fundamental inversion of property rights occurs in Eichhorn’s proposal. That is, although the conversion of a private property into public ownership might stand in opposition to rapid privatisation, Eichhorn’s proposal in fact reinforces the ever-deepening ties between individual sovereignty and property ownership in the neoliberal market. Indeed, what could be more assertive of the exclusive rights over property than having the potential to acquire a building from those who can no longer maintain ownership, and then change its legal status as defined by the Greek government? Despite the trails of legal documents that anonymise Eichhorn’s presence to a degree, it is, after all, her authority that advances this proposal, as opposed to the ever-growing precariat without a roof over their head.

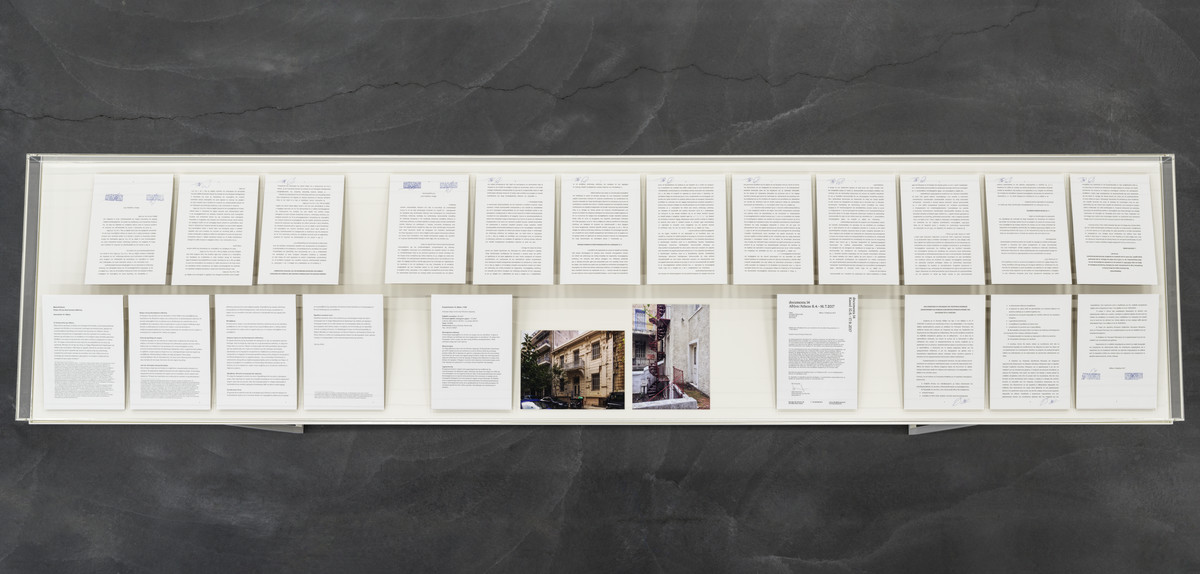

Yet the deal with 15 Stavropoulou ultimately fell through. As Eichhorn looked for another property further south in Athens, the documents and photographs of the initial property were acquired by and displayed at Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich, for the exhibition Maria Eichhorn: Zwölf Arbeiten/Twelve Works (1988–2018) from 2018 to 2019 FIG. 8 FIG. 9. When asked why the acquisition did not come to fruition, the explanation given by Eichhorn and the Migros Museum was banal. The property, they explained, did not prove suitable ‘as there were too many different parties which owned shares of the building’. The curator elaborated that due to the ‘obscurity’ of the ownership structure, the acquisition process ‘would have been extremely complicated’.28

The unsuccessful actualisation of the proposal then poses two questions relative to the form of the work: first, what are we to make of the few months that the property seemingly fulfilled the physical manifestations of Building as Unowned Property? Second, what about the enactment and the lives of the supplementary documents, particularly after 15 Stavropoulou became decoupled from the project after documenta 14? In addressing the first question, the performance of Building as Unowned Property as a work of art and the performative nature of property converge. Some legal scholars have argued that property is best defined not by legal measures or agents, but through the performances enacted within and upon it.29 The performances of ownership may range from building fences to wilfully breaking down the property, conditioned within socio-economic environments. In the context of austerity Greece, these performative dimensions are especially visible: while the rightful owners have abandoned their properties by refusing to take care of them – rather than through paperwork – others have occupied buildings, thus making an ownership of their own. Greek law, as well as those of many other countries, recognises these dimensions, declaring that after twenty years of such occupation, the change in ownership can be recognised. That the private property at 15 Stavropoulou was able to perform and be recognised as an unowned property may serve as yet another attestation to Eichhorn’s ability – or more aptly, certain individuals’ power – to dictate what constitutes private and public ownership.

By the same token, with 15 Stavropoulou no longer in the picture, the status of the documents is rendered ambiguous: do the documents morph into a synecdoche, whereby in the absence of an actual building, they stand for the entire work and enact the symbolic and temporal violence of cultural hegemony? Or, sustained in the liminality of a bygone and a yet-to-be fulfilled promise, does the work pave a new mode of reflection in contemporary art, whereby the ethical issues of public artistic intervention relative to temporality and power are illustrated, yet never enacted?

In February 2020 an appropriate property for the work was found. Eichhorn purchased a largely demolished building on a plot in Athens at 21 Iasonos using funds provided by the Migros Museum. About 3.2 kilometres from 15 Stavropoulou, the new property is far from the former glories of Plateia Amerikis and its histories of neo-classicism. Located near Plateia Koumoundourou, and a stone’s throw from one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Athens Psyri, 21 Iasonos ushers in a different set of temporalities and attendant issues: the Greek counterculture in the late nineteenth century; the severe ruins left in the aftermath of wars throughout the twentieth century; and the rapid gentrification in the early 2000s, ushered in by the 2004 Olympics Games in Athens and its pretentions of offering economic growth under the brash display of nationalisms. In an image dated February 2020, the property at 21 Iasonos is hardly the building it once was. In its stead, we see a mound of debris – plastic bags, empty water bottles, bins, a wheel – all enmeshed within verdant shrubs. Only a sliver of a cobblestone wall stands erect on the front right corner. The entire lot is barricaded by wire fencing. In discussion with the curators at the Migros Museum on 13th June 2020, Eichhorn stated that the work will be finished when the Greek government confirm the status of the property as a monument.30 The documents generated from this new stage include certificates from a topographer and the Hellenic Ministry of Environment and Energy; a topographical map of 21 Iasonos and its confirmed documentation with the city land registry; and a notarised purchase contract. In an email exchange as recent as June 2022, the Migros Museum confirmed that discussions between the artist and the museum are actively ongoing, and additional documents, such as the contract of acquiring the new property, will be included in the final form of the work.31

More than three years after the exhibition at the Migros Museum, and five years after documenta 14, Building as Unowned Property and its iterative forms continue to change. Indeed, in a nod to the continuing process of the work, the museum changed the date of the work from the finite ‘2017’ to ‘2017–’, until whenever the artist deems the work to be finished. It is the unresolved status of Building as Unowned Property – as an ongoing work of art both with and without an associated property – that allows us to probe the contours and the enactments of institutional critique. In the end, the work may be not so much about mounting ‘permanent structural changes’ from within, but more a poignant reflection on what works of art can enact and under what premise – symbolic violence or otherwise.32

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Pamela M. Lee, whose seminar on globalisation inspired this essay, and for her encouragement and critical advice. The author would also like to thank Joanna Fiduccia for her invaluable feedback on earlier iterations of the essay and Gregor Quack for his attentive reading. Finally, the author extends her deepest appreciation to the studio of Maria Eichhorn and Migros Museum for their endless help and patience throughout the writing process.