Intent in the making: the life of Zoe Leonard’s ‘Strange Fruit’

by Nina Quabeck • May 2019

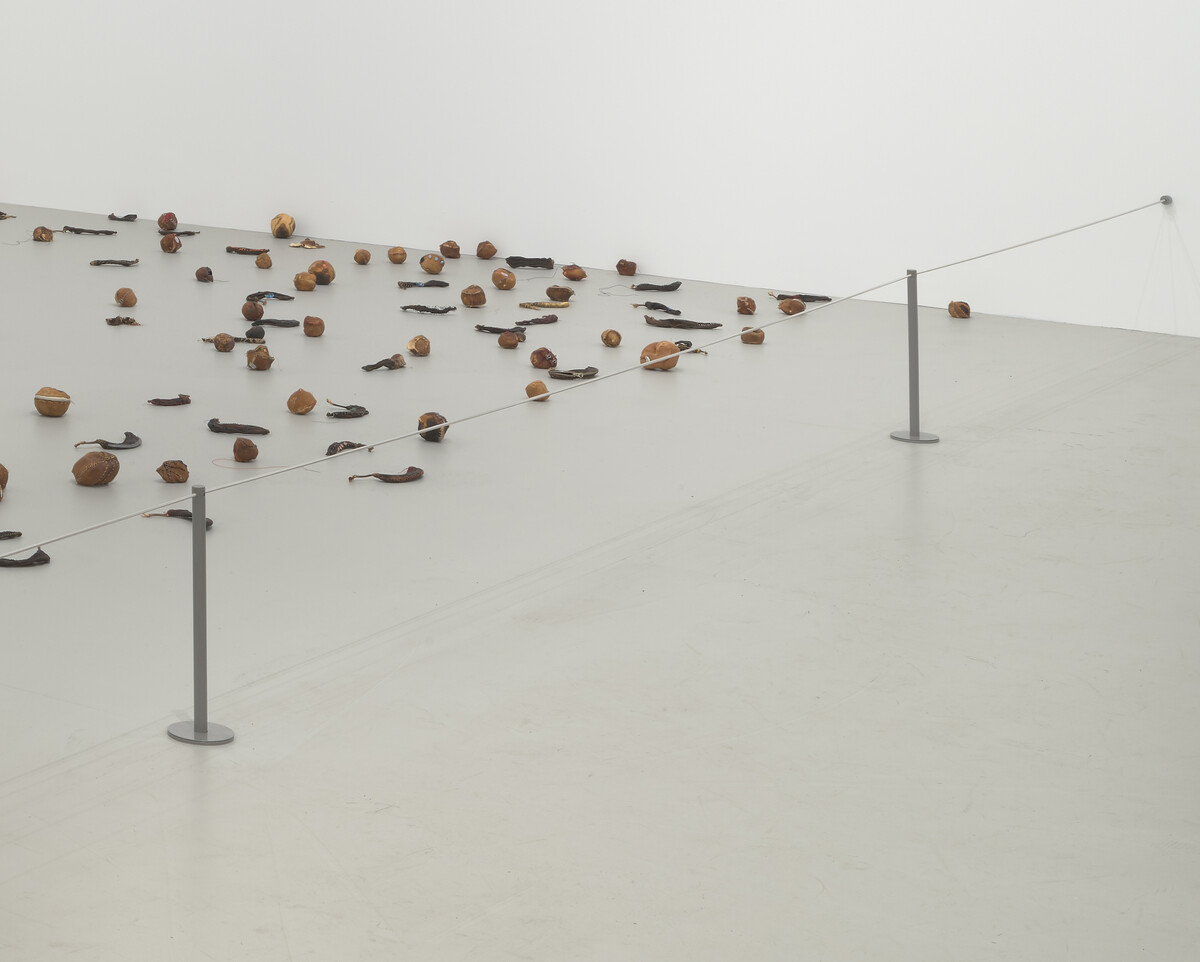

Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit (1992–97) consists of some three hundred fruit skins – bananas, oranges, grapefruits, and lemons – consumed, then stitched back together by the artist with brightly coloured thread and wire. The work was made in the 1990s, during the global AIDS crisis that devastated communities in New York, where Leonard was living and working.1 After the conservator Christian Scheidemann conducted an intensive investigation into preservation options for the fragile objects, Leonard determined the meaning of the piece: that it was made to decompose and that the organic process of decay should be allowed to unfold in public view. Promising to embrace Strange Fruit’s ephemeral nature, the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) acquired the piece in 1998. Yet a work of art meant to change and ultimately disappear challenges the traditional paradigm of museums, which is centred around safeguarding physical objects that are largely perceived as static. Contrary to an understanding reached between the artist and the museum when Strange Fruit was acquired, the work was removed from public view in 2001. It resurfaced in 2018, when it was loaned to the exhibition Zoe Leonard: Survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York FIG. 1.2 The biography of Strange Fruit, from conception to realisation to institutionalisation,3 provides an opportunity to reconsider the notion of the ‘artist’s intent’. Following Rebecca Gordon’s and Erma Hermens’s formulation of the concept in 2013, the pursuit of intent in art research is not rooted in reconstructing the artist’s state of mind at the moment of the work’s creation, but in striving to understand the decision-making that shapes a work of art.4

Reflecting on the turbulent period during which Strange Fruit was in development, the artist Gregg Bordowitz recalled the constant arguments he had with Leonard: ‘To the barricades!’ versus ‘To the studio!’, to which Leonard deadpanned that they ‘did both and got arrested together a lot’.5 Yet Strange Fruit is not an activist work. Leonard herself insisted that when she retreated to remote Provincetown, Massachusetts, in the winter of 1992, the process of mending the fruit skins was not art-making but rather her way of dealing with the trauma of losing many of her friends to AIDS: ‘Over the year that I was in Provincetown I started sewing these things, obsessively, by myself’.6

She explained that the gesture of sewing was borrowed from her friend David Wojnarowicz.7 By sewing up wasted peels instead of discarding them, the artist created objects that resemble little bodies FIG. 2. At a time in which her dying friends were treated as disposable by most of the public, the government and the medical community, the task may have offered a defiant respite. Leonard described sewing as a sort of meditation, a private act of mourning:

This mending cannot possibly mend any real wounds, but it provided something for me. Maybe just time, or the rhythm of sewing [. . .] Once the fruit is eaten, I sew it closed, restore its form. They are empty now, just skin. The fruit is gone. They are like memory; these skins are no longer the fruit itself, but a form reminiscent of the original. You pay homage to what remains.8

With this reflection, the artist eloquently put into words her keen awareness of the futility of her self-set task. Yet the task served the purpose: the process allowed her to pay homage, to remember.

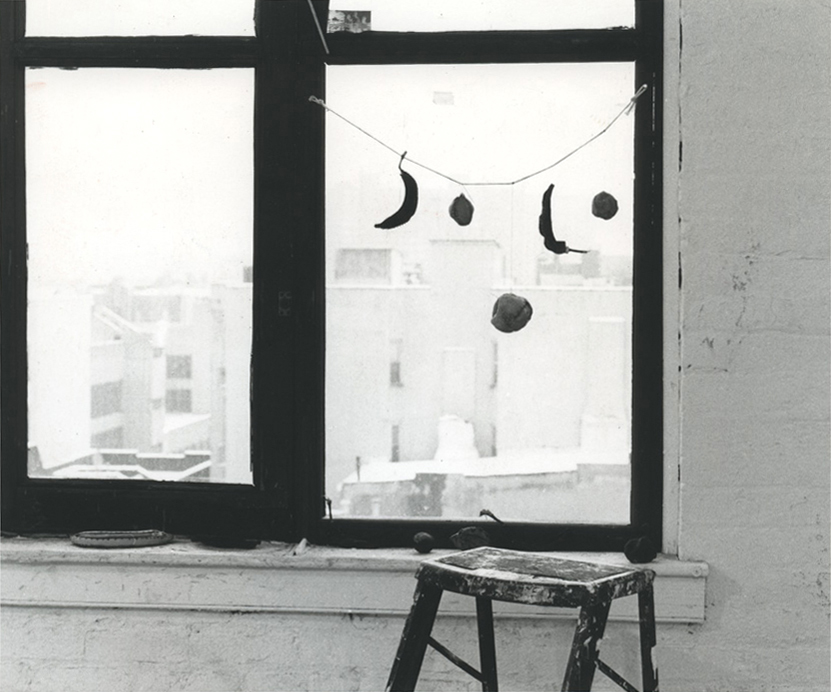

While the creation of the sewn fruit took place in the artist’s studio, their transformation into a work of art involved other people and complex negotiations. Leonard continued sewing during a stint working on a farm in Alaska in 1994, where she relied on friends sending fruit and other treats to her remote outpost. Leonard began exhibiting the sewn fruit in 1995, first at her own studio in Photographs and Objects FIG. 3 and then at Galerie Jennifer Flay, Paris FIG. 4.9 In both these manifestations of the work the sewn fruit were arranged on windowsills, on shelves, in piles on the floor and suspended from string. Since individual pieces were sold from these exhibitions, the topic of preservation percolated to the forefront of discussion. Leonard remembered: ‘In order to have it go out in the world and be sold or whatever, Paula [Cooper, Leonard’s gallerist] suggested I preserve it’.10 In response, Leonard approached Scheidemann to investigate the option of arresting the decay of the fruit skins.11

The letters between Leonard and Scheidemann discussing the experiments conducted by the conservator testify to the extent to which the artist relied on Scheidemann’s physical samples to develop the work FIG. 5.12 In December 1995, for example, the conservator sent a test example of one banana to the gallery, and wrote to the artist: ‘The procedure in total took several months to exchange the water by a sucrose solution. The finish has been executed with talcum powder to get a skin-related surface. Please let me know if this is the way it should look like’.13 The treated banana was posted to the artist in Alaska. Leonard then clarified with Scheidemann that the project would involve preserving empty, sewn fruit skins in different stages of drying. She hoped it was possible to capture the process when the fruit skins had already undergone some changes and entered a dried state: ‘There is a certain amount of variety in the stages of decay and I suppose the challenge here is to find a method of preservation that will work at arresting the process of decay at any stage’.14

Scheidemann continued making samples, and soon achieved near-perfect results FIG. 6. Once Leonard experienced these ‘frozen’ samples however, she changed her mind. She recalled:

Over the course of the couple of years where Christian and I were sending things back and forth [. . .] basically Christian went all the way, each version was better than the other. But, actually going through this process, and holding them [his samples], and being like, this is the ideal preservation of the piece, made it clear to me that the very meaning of the piece would be undermined by preserving it.15

Thus, she reached the decision that the fruit skins should be allowed to decompose, because having the work ‘frozen’ in decay would not adequately illustrate her idea. She did, however, ask the conservator to preserve twenty-five sewn fruit pieces, which would ‘function on their own as sculptures + also serve as a documentation of the piece’s life and change’.16 The preserved objects were eventually integrated into the work. Scheidemann reflected on Leonard’s decision not to preserve all the sewn fruit:

I think it [the artist’s change of mind] came after I told her that decay is not something that always adds on in perpetuity, that decay is always the same, and at one point it will all be powder. I told her that the process of disintegration is very radical in the beginning – from the ripening of the fruit to removing the fruit from the skin and letting the skin oxidize, and all this. At one point, once the moisture is removed, it slows down. I always found that decay gradually slows down, at one point it doesn't really stop but it becomes very minimal once the moisture that promotes the decay is removed.17

Scheidemann later recalled that he had also indicated to Paula Cooper that the untreated fruit peels might last a long time: ‘I told her that if the fruit are handled with great care, they might easily last fifty years’.18 Having lived with the pieces in her studio for five years, Leonard would have been able to validate the conservator’s prognosis through her own observations. Thus, after long deliberations, the artist decided not to undertake preservation measures for Strange Fruit. Once the installation entered the international art circuit in 1997, Leonard asserted the importance of its transitory nature in an artist’s statement.19

Her statement stresses that time is a co-creator of the work; decomposition is understood not as damage but as process.20 Yet ephemeral artworks, with their unforeseeable duration, uproot the museum system of safeguarding physical objects largely perceived to be static rather than in flux. Because works of art traditionally have a physical form, they are supposed to endure once they have entered the ‘safe haven’ of the museum, not least because the presence of certain artworks gives collections their identity.21 This craving for permanence can be attributed in part to the economics of collecting, since works of art also constitute a form of museum currency:22 the stable art object can be loaned and thus bartered with, while the deteriorating work is seldom deemed presentable, nor loanable, and is thus retired to storage (or conservation) and withdrawn from the loan circuit.

In 1997 Strange Fruit was shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art Miami, Kunsthalle Basel and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York,23 and was presented differently in each iteration: in Miami the work was installed on the floor, while in Basel the pieces were arranged on shelves FIG. 7, and for the exhibit at Paula Cooper Gallery it was once again on the floor. Zoe Leonard’s wish to display the sewn fruit while they decomposed hinged, however, on the existence of a permanent space for the work to reside in. Strange Fruit’s accessioning by the PMA in 1998 was the subject of an influential essay by the museum’s curator Ann Temkin.24 Published the following year, the essay succinctly explains the extensive research and experiments that Scheidemann undertook for the artist, and divulges the intricacies of the acquisition process. Temkin reported on the museum’s concerns, recalling that there was discomfort among the acquisitions team about assigning an accession number to something ‘that won’t always be there’.25 Once Temkin reserved the piece for the museum, the process of negotiating it into the collection began.

Having identified the decay of the fruit skins as the vehicle for the idea of the work, Leonard was ‘initially deadset against the idea of placing the work in the museum’, as the PMA signalled they were not prepared to dedicate a permanent room to the work. However, she later embraced the idea because ‘it provided a very tempting context’.26 Leonard also confirmed that Temkin came to her studio repeatedly to persuade her that the compromise would be worthwhile.27 Temkin’s support for the transitory nature of Strange Fruit is underscored in the press release issued by the museum on the occasion of the work's acquisition: ‘Unlike a painting, Leonard’s Strange Fruit is intended to be transitory itself, and will deteriorate and eventually disappear over time, a process that will be documented through photography’.28 Nevertheless, Leonard insisted on drawing up a ‘letter of intent’ for the work together with the curator, which is documented in the Paula Cooper Gallery Records at the Smithsonian Museum of Art in Washington.29 An early draft of this letter reads:

I am thrilled that the Philadelphia Museum of Art has acquired Strange Fruit. Due to the unusual nature of the work, I would like to record my understanding with the artist on a number of points. We would like to display the piece at regular intervals over time, until it becomes too fragile to show. In keeping with the spirit of marking time, we will try to show it, as possible, during a period that is consistent from year to year. The successive installations will be documented by our staff photographer at their start and finish. The artist is also welcome to photograph the installations. We will jointly evaluate the decay of the work and decide when it can no longer be exhibited, and/or when the manner of exhibition should change.30

This document provides a unique insight into the negotiations between artist and institution. Both parties were evidently eager to determine the extent of the museum’s commitment with regards to the acquisition of Leonard’s work. While Temkin makes no mention of this letter of intent in her essay, she relayed that Leonard ‘presented to us unexpected questions about our willingness to show it continuously, to devote a specific space to it, and to show it, still, when it becomes more evidently a ruin’.31

Following its acquisition, Strange Fruit was on view in Philadelphia from April to September 1998.32 An installation view shows the sewn fruit scattered across the gallery floor FIG. 8. There appears to be space for visitors to walk among the objects. Yet, for a portion of the museum’s opening hours, the public was prevented from entering the space as the two entrances to the gallery were barred with Plexiglas panels. For four hours each day, during which a guard was reportedly stationed in the room, viewers were allowed to enter the space and walk among the fruit.33

Strange Fruit was afterwards loaned to an exhibition at Gallery Anadiel in Jerusalem in 1999 and presented once more on its return to the PMA. In an article of 2002, Sylvia Hochfield mentions that Leonard installed the work at the PMA more than once, so it seems likely that the artist came in to reinstall the work on its return from Jerusalem.34 According to the conservator Gwynne Ryan, who was working at the PMA as a Mellon Fellow in Sculpture Conservation at the time, the work was deinstalled in 2001.35 In 2000 Leonard wrote to Temkin after the PMA approached the artist with the idea of presenting a detail of the piece, or alternatively to present it on ‘shelves, walls, or in cases’; suggestions that Leonard viewed as a clear breach of their previous agreement:

Strange Fruit did go through a long evolution, before it was even titled Strange Fruit – varying numbers of elements, installed on windowsills, shelves, in piles and on the floor. At the time of acquisition, the configuration and placement of the elements had been defined, and these aspects of the work should not be altered. Although the individual elements continue to age, fade, and change, the conceptual and formal aspects of the piece must remain constant.36

She makes a crucial point: that the conceptual integrity of the piece must be respected. While ephemeral artworks are generally viewed as physically vulnerable, the procedures in place at the PMA highlight that they are also ‘conceptually vulnerable’.37 Leonard continued:

In our long and complex negotiations proceeding [sic] the museum’s acquisition of Strange Fruit, we spoke a great deal about allowing for the time-based aspect of the work. Although the museum signed no legally binding contract, I was led to believe that Strange Fruit would be exhibited on a regular schedule, for long periods of time. As you know, my original vision for Strange Fruit was to install it permanently somewhere, so it would be on view continuously as it changes. It was a compromise to agree to have it exhibited intermittently, rather than on permanent display. It seemed a good compromise because of the wonderful context of the museum’s collection, and your enthusiasm about Strange Fruit. There seemed to be an understanding that the process of slow disintegration is integral to the artwork, and that it is essential that this process is visible. I trusted that the regular schedule of exhibition would adequately express the time-based aspect of the work, and I trusted that the museum was committed, even eager to follow through.36

In spite of Leonard’s letter, the work was not on display from 2001 to 2018,39 during which Strange Fruit was subjected to standard museum preservation procedures. The PMA’s former chief conservator Andrew Lins confirmed in an interview with researcher Lizzie Frasco that the objects undergo active conservation treatment before and after a loan, such as treatment for mould and insect damage.40 According to the conservation theorist Heinz Althöfer, transitory works (in his terminology: ‘ruinous artworks’) require a ‘completely different conservation mind-set than traditional artforms’; Althöfer pointed to Dieter Roth’s sculptures made from perishable materials to make his point: while conservators are right to battle a bug infestation in a Rubens panel painting, they would eliminate Roth’s ‘assistants’ if they chose to combat the beetles in his chocolate objects.41 Frasco, expecting to find only ‘remains’ of the work when conducting her visit, was perplexed by the PMA’s modus operandi: ‘The insects, mold, and agents of decay that are treated are the very mechanisms by which Leonard foresaw the work decaying’.42

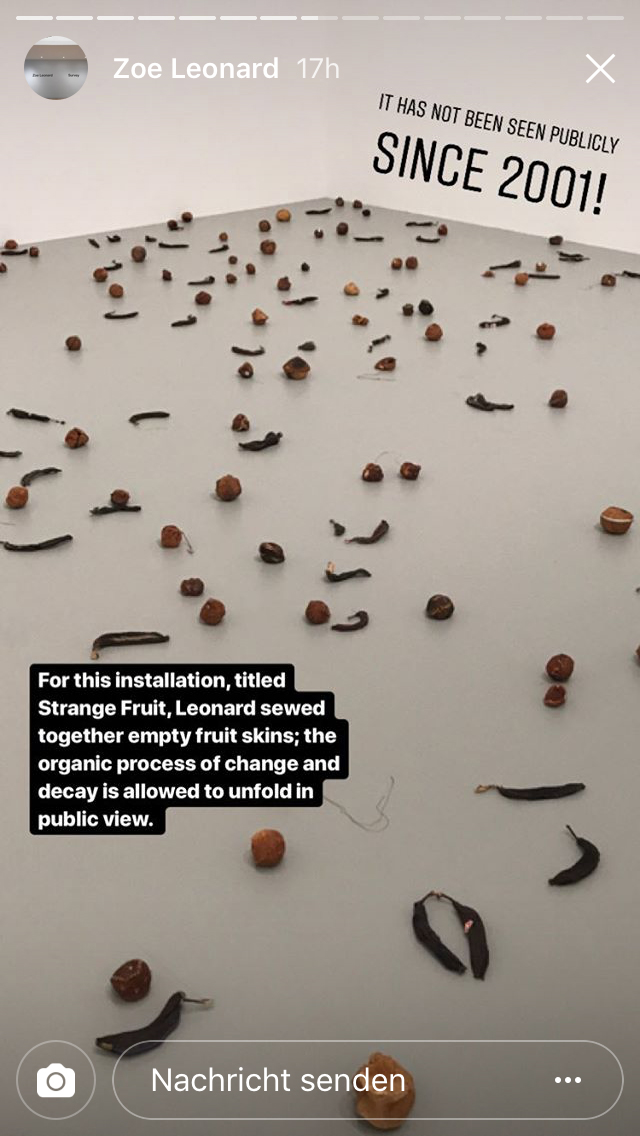

It appears that the work’s non-display reflects institutional priorities. It could be argued that Temkin’s transfer from the Philadelphia Museum of Art to the Museum of Modern Art in 2002 was a turning point in the work’s post-acquisition life, for with this change of staff Strange Fruit lost its most dedicated champion. Displaying the installation required considerable resources: a full-time guard as well as constant attention from the conservation team, readjusting pieces as they moved, and securing fragments of those pieces that were accidentally stepped on. Without Temkin’s advocacy, this may have been seen as too great a cost. The museum’s treatment of Strange Fruit caused a rupture in the work’s intended behaviour. Leonard sought a buyer for Strange Fruit who would commit to maintaining the work in its ongoing decomposition, displaying it frequently, if not continuously. The artist’s frustration over this period of unwanted dormancy was made obvious in an Instagram post on the feed of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York FIG. 9, in the days leading up to the opening of her exhibition there.

The loan negotiations for the 2018 exhibition shed light on the PMA’s stance towards Strange Fruit’s time-based nature. Margo Delidow, a sculpture conservator at the Whitney, described the pre-loan negotiations around the work as so extensive that, once the work arrived at the museum, it was one of the easiest to install.43 Delidow attempted to accommodate the artist’s wishes for displaying the work: Leonard was concerned the Whitney’s wooden floor would be too much of a distraction, so they agreed to present Strange Fruit on a grey vinyl floor covering. However, the PMA vetoed the use of vinyl as the material does not pass the Oddy Test – an accelerated corrosion test used by museums to ensure that materials will not damage works of art. The flooring ultimately chosen for the Whitney display was wooden boards painted grey FIG. 10.

Leonard did however succeed in securing permission from both the lender and the borrower to handle and install the sewn fruit herself. The artist’s wish that crushed fruit pieces would be placed among the group, their fragmented skins forming little piles on the floor, was also accommodated. Their presence enhances the work’s aura of transience, their disjointed state another potent reminder that these efforts at repair will eventually become futile, with nothing of the work left but fragments, crumbs and finally dust. Then, crucially, the PMA declined to lend the work to the co-organising venue, MoCA Los Angeles, for the second leg of the tour. Leonard explained that this was due to the fact that the exhibit took place at MoCA’s Geffen Building, a warehouse without climate control or a pest management plan.44 Uncomfortable with the idea of the work being destroyed by pests after having only just been released from storage, Leonard did not press PMA to lend the work, and left the decision with the curators

Leonard’s intent for her work – to be regularly on view so that change taking place in the sewn fruit skins over time can be appreciated by the public – is clearly documented in the correspondence between artist and museum. And even though these stipulations were not manifested in a contract at the point of acquisition, Temkin unambiguously and publicly stated them in her essay. These circumstances constitute a clear ‘sanction’ or ‘enacted intention’.45 Yet the work was retired to storage for seventeen years, a choice that has effectively prevented the intended change from taking place. This has in turn left the artist with the question how to ‘realign her intent for the work’ after its biography took such a different course from the one she had expected. How, then, is this to be seen in view of the legal guidelines?

The quest to protect the moral rights of artists is rooted in the ‘presumed intimate bond between artists and their works’.46 Artistic moral rights are based on the assumption that the work is inalienable from its creator due to the personal and spiritual contribution that links it to the artist, even though it is put into circulation and up for sale. Thus, works of art are ‘owned’ by two parties at once. As K.E. Gover argues, ‘The collector or museum may own the object, but unlike other kinds of property, the owner cannot simply do whatever it wishes with the artwork because the artist continues to be linked to that object through personality and reputation’.47 The pitfalls of balancing the ownership rights and responsibilities of two such parties have been illustrated by several prominent lawsuits, including the controversy around the removal in 1989 – unauthorised by the artist – of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981) from Federal Plaza, New York, or the 2007 controversy at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary art (MASS MoCA) concerning its decision not to complete Christoph Büchel’s Training Ground for Democracy.48

To further complicate the matter, the 1988 Berne Convention, which protects the moral rights of artists, relies on national implementation.49 In the United States, the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), passed by Congress in 1990, is a provision of copyright law intended to incorporate noneconomic rights of artists, or ‘moral rights’, into national law. VARA grants American artists the ‘right of attribution’ (the right for artists to be identified with their works) and the ‘right of integrity’ (the right to protect their work from modification and destruction).50 Does the failure to display Strange Fruit constitute an infringement of the artist’s right under United States law? To date, the legislative discourse on artist intent and conservation is scant.51 VARA in fact specifies that ‘the modification of a work of visual art which is the result of conservation, or of the public presentation, including lighting and placement, of the work is not a destruction, distortion, mutilation, or other modification described in subsection (a)(3) unless the modification is caused by gross negligence’. Thus, under VARA, a museum may be liable to an artist only for the intentional or grossly negligent destruction of a work. In her paper ‘The right to decay with dignity’, Katrina Windon attempted to disentangle how VARA might be applied to protect artistic intent, but surmised that artists have the right to determine that their works are not intended to last only ‘so long as he or she has not entirely signed over that right to another’.52 Zoe Miller suspects that the integrity right is ‘predicated on a notion of material stasis’, which appears to amount to ‘a legal obligation to preserve material form’.53 She concludes that the integrity right fails to protect the artistic intent when this requires a work to change and to disappear. From a legal point of view, one might therefore surmise that by agreeing to the PMA’s acquisition of Strange Fruit, Leonard gave up her work’s right to disappear. With VARA privileging physical integrity over concepts, artists may have to resort to contractual agreements at point-of-sale, which offer artists effective means for controlling the exhibition of their work ‘after its sale by imposing legally enforceable obligations on the collector/museum’.54

An understanding of intent as fixed or unilateral is short-sighted, indeed inadequate, in the context of art research. The findings presented in this article suggest a new model for understanding intent in which the outlook is shifted from the perception of the artist’s voice as the ultimate and sole authority towards a more pluralist and open-ended view. It might be reframed as ‘intent in the making’:55 even with works of art that appear to be settled in terms of art history, intent is still in the making because the decisions made around these works of art is ongoing. Tracing the steps of Zoe Leonard’s decision-making in this account of Strange Fruit’s biography, it is clear that her intent for the work evolved over time, that it responded to circumstances and that it was subject to negotiation. Leonard relied on Scheidemann for preparing samples of preserved fruit to develop the work’s final form, and for his advice and discussion on the processes. The accessioning of Strange Fruit, especially the artist’s and the curator’s collaborative ‘letter of intent’, provide evidence of intent in flux, of being brokered over time, or remaining in the making throughout the life of a work of art. Museum workers’ interpretations of artistic intent will affect the lives of the art under their care. Acknowledging institutional intent makes us aware that it is, in that sense, as important as the artist’s, and asks the question: just whose intent it is that we are prioritising?

Acknowledgments

This paper, which is based on the chapter of the same title of my forthcoming Ph.D. thesis, ‘The artist’s intent in contemporary art: matter and process in transition’, has been made possible through the generous support of a number of people, first and foremost Christian Scheidemann and Zoe Leonard. I am indebted to Paula Cooper and Ann Temkin for taking the time to meet with me, and to Margo Delidow, and to Allison McLaughlin, Sally Malenka and Carlos Basualdo at The Philadelphia Museum of Art for their kind support of this research. Laura Hunt, former archivist at Paula Cooper Gallery, also provided immeasurable support. Thanks are due to Zoe Miller for patiently delineating the intricacies of the implementation of artist's moral rights. Lastly, my thanks to the critical readers of the chapter drafts and versions of this paper: Dominic Paterson, Erma Hermens, Cornelius Quabeck, Franziska Quabeck, Brian Castriota, Caitlin Spangler-Bickell and Diana Blumenroth.