‘I believed in the image’: Pope.L, photography and the spectacle of racial oppression

by Martyna Ewa Majewska • June 2022

We can never really look at a photograph without looking through it as a document. In this way art allegorizes documents, granting us the chance to consider Atget not simply as an auteur but as a working man with motivations, intentions, imperatives and pressures that were as complex as anyone’s.1

This quotation comes from David Campany’s essay on Eugène Atget (1857–1927). Although the present article does not concern itself with Atget’s photography, it proposes that similar consideration be given to photographs of performances – specifically, photographs of street performances staged by Pope.L (b.1955) in New York between the late 1970s and the early 2000s. By attributing complex motivations, intentions and imperatives to the photographic processes involved in the orchestration of those performances, this article seeks both to acknowledge these photographs as records of performance and to expand beyond a purely documentary reading of performance photography. In so doing, it will show that photography – and the conscious deployment of photographic framing in particular – has been a vital aspect of Pope.L’s performance practice, which has repeatedly found its locale in bustling, volatile street spaces. Often populated by accidental, live audiences as a result of their siting within the urban environment of Manhattan, Pope.L’s open-ended performances should be viewed as integral to his strategy of purposeful production of images.

This approach is not new. Scholars including Amelia Jones, Philip Auslander and Kathy O’Dell have argued, in distinct ways, that photography should not only be treated on an equal footing with live viewing, but that it completes and contributes to performances.2 Yet projecting this perspective onto photographs generated by street performance is more complicated, especially in cases where the originary acts were staged in highly policed spaces and locales populated by uncontrollable audiences as opposed to the more restricted gallery-going audience. In such cases, photographic images of performances intervene not just in debates on documentary photography, they simultaneously invoke and defamiliarise street photography and its traditions.

Equally, there are other artists who have situated their performances in street spaces – a great many also in New York – and invited photographers to produce images of their actions. Notable examples in the United States include Adrian Piper (b.1948), David Hammons (b.1943) and Sharon Hayes (b.1970). The conscious planning of street performances to create particular images and the attention to isolating specific frames while being confronted with live witnesses that we discern in Pope.L’s work are also evident in the work of these three artists, as well as many others.

Pope.L’s methodology is nonetheless unique. Hammons’s street performance photographs are identified as shot by either Bruce Talamon (b.1949) or Dawoud Bey (b.1953); Piper was famously photographed performing on New York’s streets by her friend and fellow artist Rosemary Mayer (1943–2014), as well as other named photographers-collaborators;3 Hayes’s widely exhibited project In the Near Future (2005–) is well-known for involving photographs taken by the artist’s audiences. The photographs of Pope.L’s performances, by contrast, hardly ever identify the photographer in their captions, and it is Pope.L’s name that stands as their official creator. The artist is also known for producing quasi-philosophical discourse around his practice. This is enacted in many ways: by speaking during performances and invited talks, writing poems and essays, and by using text in drawing and painting. Within this discourse, he expressly addresses his investment in the image production of performance and the capacity of performance art to manipulate or otherwise intervene in existing imagery. Speaking of the preparations for the video performance White Baby (1992), for example, Pope.L identified ‘using images culled from the street, images utilising [his] body [and] images of disenfranchisement’ as his methodology.4

Of one of his street crawls – whereby he would drag his body, clad in an elegant suit, down the Bowery’s gutter – Pope.L has stated: ‘I did that street work over a period of several weeks, and when I first began I believed in the image’.5 From the start, then, the artist’s crawls were conceived as image-making procedures. His insistence on the image production of street performance is also reflected in the fact that so many of his pieces were both photographed and videotaped. Pope.L’s mid-career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), in 2019–20, which focused largely on the artist’s performances up to 2001, featured multiple series of photographs, some of them enlarged and rendered into wall murals, and video recordings, set alongside his performance costumes FIG. 1.6 Yet, while the exhibition positioned the photographs and videos as documentary records and points of access to Pope.L’s past performances, it is useful to reconsider them as products of Pope.L’s design – as the end products rather than by-products of his performances.

Pope.L’s early crawls resulted from an image he had conceived: what he referred to as ‘the conjunction of a black man and his suit’.7The artist consciously constructed a contradiction of himself. ‘I want people – even if it’s only the policemen who arrest me, especially policemen – to experience my contradiction’, he would go on to explain.8 Indeed, his first publicised performance, Times Square Crawl a.k.a. Meditation Square Piece (1978), generated an image in which the crawling Pope.L, dressed in a suit, appears to be stopped by a New York Police Department (NYPD) officer in the middle of a street crossing FIG. 2. Because they capture police interventions, the photographs of this and other street pieces by Pope.L conjure up the association of photography’s origins with policing, theorised most influentially by Allan Sekula.9 By fixing the Black male body in positions of vulnerability within the entangled frames of towering urban architecture and police surveillance, these photographs reveal the racialised character of public art, of the policing of public space and of risk in performance. This, it can be shown, is done by design. Pope.L’s thorough engagement with his performance photographs, exemplified by the MoMA retrospective and the accompanying podcasts the artist recorded for the museum’s website, demonstrates the importance of photography in positioning the viewer vis-à-vis his Black male body in each performance.10

Although Pope.L’s performance has its roots in experimental theatre and improvisation, the artist is also a keen image maker, working in a wide range of media, including painting and drawing. His multidisciplinary practice consistently engages symbols and stereotypes associated with Blackness, be it Thunderbird wine (an inexpensive fortified wine) or – as in the case of his ongoing Black Factory project – whatever his audiences deem to be ‘Black’. Employing puns, racial slurs and Duchampian interventions, Pope.L often subverts established circuits of artistic production, exhibition and sales. His work has been associated with the controversial performances of Chris Burden (1946–2015); like Burden’s, Pope.L’s street actions have triggered police involvement.11 Indeed, despite its seemingly humorous, almost light-hearted veneer, Pope.L street practice has also seen the artist put himself in harm’s way. Yet, if Pope.L’s works may be placed in the category of masochistic performance, so frequently associated with Burden – whose works include firing several pistol shots at a Boeing 747 passenger jet plane while it took off, and being shot in his left arm by an assistant – what puts Pope.L at risk is not the masochism of his actions, but the implied threat carried by dark skin in a racist, intensely policed society. This very threat has frequently been placed at the heart of Pope.L’s artistic projects.

Homelessness, visibility, racism

In the photograph of his Times Square Crawl of 1978, Pope.L appears to actively stage what is often referred to as ‘suspicious behaviour’ or ‘suspicious activity’ both by members of the police and those that report suspected crimes. While the artist has since performed his signature crawls in less incongruous clothing outside of the United States, the suit was his designated attire for New York crawls and other performances staged on the city’s pavements as a way of attracting public attention. By the late 1970s, homelessness, rough sleeping and addiction had brought so many New Yorkers to street level that a more casual outfit could have rendered Pope.L’s actions invisible to others: ‘It seemed as if people were devising strategies in order not to see the homeless’, the artist would remark years later.7 By confounding his witnesses, he made them face what they deliberately tried to avoid.

In the case of the 1978 crawl, the location was purposefully puzzling. On the one hand, Times Square is a high-visibility site as well as a maximum-surveillance one; on the other hand, it is a place where, seemingly, anything goes – a go-to free-of-charge performance venue outside of the gallery and theatre circuits. In the late 1970s it was still a location notorious for night clubs, striptease bars and heavy drinking. Pope.L’s outfit, therefore, could associate him with the visitors of those establishments, who would descend on Times Square from their Manhattan offices to unwind. Yet Pope.L is also a Black man crawling on a New York street, therefore likely to attract police attention by his very presence. It is precisely this contradictory image with which the artist’s crawls started.13

For all its suspicion and the confusion it may have caused, Pope.L’s 1978 crawl did nontheless clearly reference homelessness – so prevalent in New York but also continually policed into invisibility. The police-enforced removal of unhoused people from the city’s public spaces was part of a larger project of urban redevelopment that picked up steam in the 1980s.14 Rather than addressing the systemic issues that were causing homelessness, municipal authorities sought to eradicate homelessness from cities in the United States by way of ‘involuntary detention of “endangered” persons’, as detailed in Joan Kee’s analysis of art and legal structures in the country.15 While promising to redesign urban sites, the coalition forged between public art programs, architects and urban designers, in the words of Rosalyn Deutsche, ‘constructed the homeless person – a product of conflict – as an ideological figure – the bringer of conflict’.16

In the Times Square Crawl photograph, Pope.L personifies disruption. Not only does his behaviour attract a police intervention, he becomes a spectacle for passers-by. All heads are turned towards him; some faces express bewilderment or perhaps concern; the man in the background seems to be amused. Capturing these reactions, the photograph is a testament to the efficacy of Pope.L’s crawl. As the artist explains, ‘We’d gotten used to people begging, and I was wondering, how can I renew this conflict? I don’t want to get used to seeing this. I wanted people to have this reminder’.7 Hence, the crawl is not just a reminder that homeless people exist, in spite of the efforts of the police and urban planners to eradicate their presence. More vividly than the performance itself, its photographic framing fleshes out the fact that public space is shaped by conflict. It is this character that the new, sanitised media images of urban sites sought to suppress, Deutsche argues.18

The crawl photograph foregrounds conflict by centring around the police officer’s gesture towards Pope.L. But, with the photographer behind the artist’s back, this performance for the camera not only invokes the link between photography and policing, but also actively probes the boundary between visibility and invisibility in urban space. This boundary is of course conditioned by the race, class and gender of individuals and groups to whom it is applied. By generating and exhibiting the images of policing of his hardly threatening actions associated with destitution, Pope.L seems to confront us with the fraught relationship between homelessness – especially Black male homelessness – and visibility. As Adair Rounthwaite writes, unhoused people ‘tend to be both structurally invisible and physically overvisible’.19

The particular contradiction that Pope.L stages for the camera by crawling in a suit directs us to the larger set of paradoxes surrounding visibility and invisibility. Economically privileged individuals can in fact be deemed more visible – at least ‘in terms of how dominant culture represents a legitimate life’, as Rounthwaite explains – and, at the same time, less visible, because of the shelter afforded by the private domestic sphere.20 In short, the privileged can control their visibility, whereas those dispossessed, relying on public space for daily functioning, can neither claim nor disclaim it. Invisibility, in this reading, ceases to stand for structural oppression and instead constitutes a luxury, something that can be inherited and purchased – a commodity. In a racist, high-surveillance society, invisibility is not only conditioned by class but also tied to whiteness. Whiteness, too, can be inherited and reproduced, as Sara Ahmed informs us. It is reproduced ‘by being seen as a form of positive residence: as if it were a property of persons, cultures and places’.21 Complementing Ahmed’s phenomenological viewpoint, the civil rights scholar Cheryl Harris demonstrates that in a society structured by racial domination, whiteness functions as an asset, a set of privileges and benefits, which are ‘affirmed, legitimated, and protected by the law’.22 Herein lies one explanation of Pope.L’s well-known association of Blackness, particularly Black manhood, with what he calls ‘the lack’.23

A critique of photography

Pope.L’s crawl along the border between visibility and invisibility alerts us to the photographic frame, which abstracts from space and time. Put differently, the contradiction and suspicion of the scenes generated by Pope.L’s open-ended street performances caution us about the shortcomings and biases of the camera. As so many theorists have noted, photography, especially when unaccompanied by text, revels in its own selectiveness, its factographic insufficiency. In the words of Sekula, ‘The only “objective” truth that photographs offer is the assertion that somebody or something […] was somewhere and took a picture. Everything else, everything beyond the imprinting of a trace, is up for grabs’.24 Is the police officer in Pope.L’s Times Square image expressing care and concern or simply reprimanding the artist? Is it the policing that produces the spectacle, or is it the spectacle that attracts policing? What is the role of the camera in creating this spectacle? The photograph poses these questions but denies us answers. Yet it is not just the story behind the image that appears unclear. The photograph, too, necessarily eludes definition. It does not reveal whether the action was staged; it refuses to tell whether the photographer is the artist’s assistant or just a camera-equipped flâneur who happened to be on the scene. As such, the image is uncomfortably positioned between documentary and street photography.

While photographs of performances are commonly treated as documentation, the categories of documentary photography and street photography are often confused or treated as synonymous. Since, as the opening quote from Campany reminds us, ‘we can never really look at a photograph without looking through it as a document’, it is easy to see the street photographer as simply documenting the street. Martha Rosler writes that ‘documentary and photojournalistic practices overlap but are still distinguishable from one another’, but only a few lines later concludes: ‘In reality, however, many photographers engage in both practices, and the same images may function in both frames as well’.25

Yet because that which is termed documentary photography has been subject to individual appropriations and stylisations, the widespread and universal application of the term and the equation of documentary photography with truth have engendered a more vigorous critique. Just a few years before Pope.L started crawling on the streets of New York, Rosler issued a pointed indictment of documentary photography both in the form of her published texts and in her photoconceptual work The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–75). According to Rosler, what she refers to as ‘the liberal documentary’ not only appeases the viewers’ conscience but also ‘reassures them about their relative wealth and social position’.26 Rosler recognises the part played by documentary photography in preserving the status quo and in affirming the fixity of the existing situation – notably, through a particular approach to framing subjects who are unhoused and suffer from addiction. ‘Bums are, perhaps, to be finally judged as vile, people who deserve a kick for their miserable choice’, she comments on the resulting photographs.27

Rosler’s response to such afflictions of documentary photography was to evacuate all people from her photographs of the Bowery – a district of Manhattan once notorious for scenes of destitution and addiction – and to supplement them with text. These unpopulated images of the city are somewhat reminiscent of Atget’s photographs of empty streets and shop windows. In addition, to invoke critical discourse on Atget once more, the vacant street scenes he depicted have been likened to crime scenes – most famously by Walter Benjamin.28 With their emptied bottles on the Bowery’s pavements, Rosler’s photographs can be likened to crime scenes too. Refusing to represent people, they neither victimise nor make accusations. While clearly critiquing the so-called documentary photography for its codification of the street ‘bum’ into a recyclable stereotype, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems can also be shown to challenge stereotypical thinking about street photography. ‘Instead of “life caught unaware”’, as Stephanie Schwartz writes, ‘The Bowery offers viewers the frame that promises to catch life unaware: street photography’.29

The present author proposes that the photographs of Pope.L’s street actions undertake a similar, if not related, critique of photography and the associations that have clung to both ‘documentary’ and ‘street’ modes at least since the landmark photography exhibitions organised by John Szarkowski at MoMA in the late 1960s and early 1970s.30 That said, when juxtaposed with Rosler’s project, Pope.L’s critique takes a visually different route. Rather than evacuating the stereotypical bum from the street, the performance photographs defamiliarise him. Rejecting Rosler’s refusal to represent the low and the lowly, Pope.L’s performance photographs exploit and manipulate this kind of representation. By including the concentrated stares of live witnesses, the photographic framing highlights the status of the ‘bum’ as a spectacle. Thus, rather than resembling a crime scene, Pope.L’s Times Square photograph captures the crime itself: the crime of being on the street, struggling and Black, as signalled by the police officer’s intervention. Pope.L serves us the spectacle of victimisation typical of documentary photography, and often seen in the photographs of police violence that register as street photography, but he disrupts our numb consumption of the spectacle by inserting himself as an element that contradicts the stereotype.

Between street and documentary photography

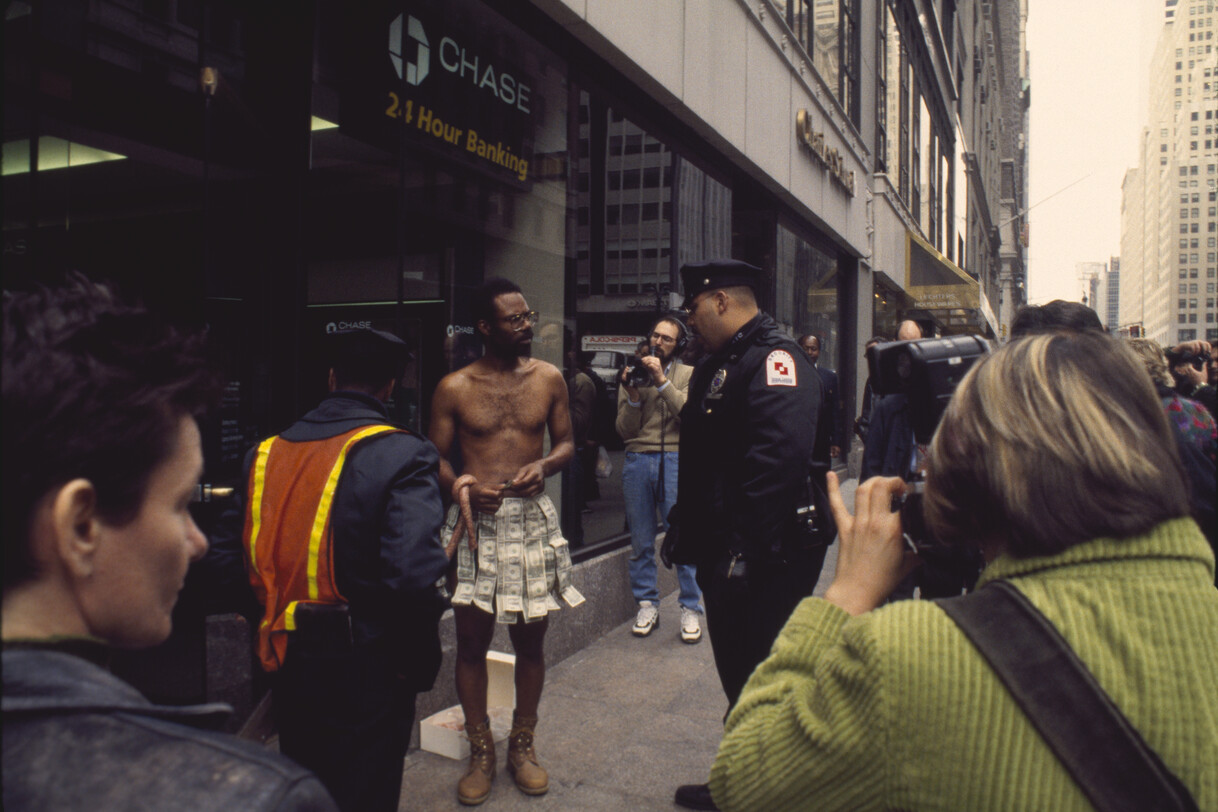

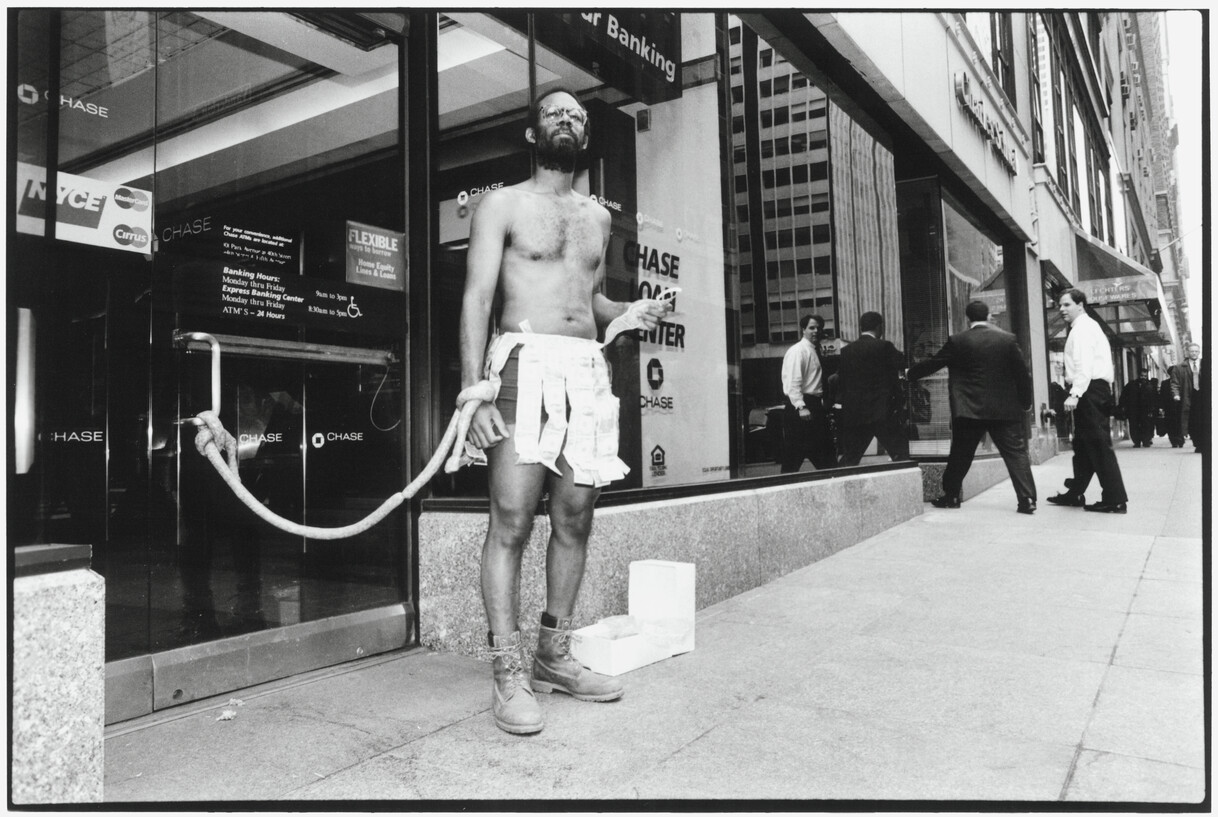

Pope.L has repeatedly used the strategy of turning a stereotype on its head – always in front of the camera. A clear example is provided by the photographs of his ATM Piece of 1997 FIG. 3. Organised outside a CHASE bank near the Grand Central Terminal, the piece entailed Pope.L, dressed only in a hula skirt made of dollar bills and Timberland boots, chaining himself to the ATM vestibule with Italian sausage. The bank’s security guard called the police almost immediately after the artist started the performance. Pope.L had not only predicted such a response, but he knowingly triggered the confrontation by invoking the racist stereotype of the Black panhandler and playing with the strict prohibition of panhandling within ten feet of an ATM. Yet in this performance too a contradiction was introduced: standing near the ATM, the artist handed out dollar bills from his skirt to passers-by. Meanwhile, the absurdist sausage chain was intended to prevent a more violent response from the security and police. As Pope.L explained, he did not want to be seen as ‘impinging on [the bank’s] property in some, quote, terrorist sense’.31

Some photographs capture what looks like an altercation between the artist, the police officer and the security guard, but others include more. Given that this is another high-visibility location, witnesses are expected to creep into the scene. When compared to the Times Square Crawl photograph, here the atmosphere of all-encompassing surveillance is much more pronounced. While the central action is framed by the ATM vestibule and its highly efficient monitoring system, as signalled by the guard and the police officer, the surrounding crowd is not just looking. Among the witnesses are two people equipped with cameras, standing on either side of the scene. The frame thus captures documentation itself. Looking at these snapshots, we may be inclined to ask, if the person in the green jacket is taking photographs and the one in the beige jumper behind Pope.L is recording a videotape, who produced these images? The question remains unanswered – officially at least.

Although Pope.L sometimes references the names of his collaborators – notably the photographer Lydia Grey and the videographer James Pruznick – he does not include them in his image captions in gallery and catalogue labels, claiming the photographs of his performances as his own work.32 While, as noted earlier, this decision suggests Pope.L’s agency and investment in the production of the images, it also affects the viewer of the photograph. The images of Pope.L’s street performances install their beholders as members of the public, as potential documentarians or street photographers of the event. In this way, we become complicit in the system that produces and facilitates the scene, implicated not just in the spectacle but in the making-of this spectacle. By never naming the creator of the photograph, Pope.L positions us as participants in both spectacularising and consuming him.

The suite of photographs selected to represent ATM Piece on MoMA’s website, in which Pope.L’s agency in framing is so evident, features not only the images of the performance itself but also of the publicity it elicited. The same person captured taking photographs of the half-naked Pope.L during the performance, with blonde hair and a green jacket FIG. 4, can be spotted in another image FIG. 5. In it, Pope.L is seen wearing a much less conspicuous costume, consisting of denim shorts and a black jacket. The artist and the photographer are accompanied by another person, who is taking notes; Pope.L appears to do the talking, while the two women listen. Because another photograph of Pope.L’s piece FIG. 6 was published in an article covering the performance in the Village Voice in March 1997, we can easily identify the photographer wearing the green jacket as Catherine McGann and the note-taker as the writer and critic Cynthia Carr.33 Notably, in the McGann photograph, which is not included in the museum presentation of Pope.L’s performance, the artist is pictured performing undisrupted, handing out the dollar bills to the implicit street audience. This suggests that McGann was there from the beginning, before the security and the police were called: presumably she was informed of the performance and was commissioned to cover it for the Village Voice. The discrepancy between McGann’s photograph and the images on MoMA’s website further confirms that Pope.L selected those snapshots where the police intervention took centre stage, the ones that seemed to have been taken by an anonymous street photographer.

It is pertinent to ask, then, why an image of Pope.L conversing with the two reporters would be included in a suite of photographs that now collectively stand for the performance. For one, the image underlines the work’s public, headline-making and spectacular character. It also draws the viewer’s attention to the processes of performance art’s image production and discursive framing of the artist’s body. Pope.L’s creative agency in these procedures is, yet again, made plain, as it is he who is captured speaking to the two listeners. This is a thread that runs throughout Pope.L’s practice: he forces viewers to question what is often perceived as factual or transparent. Just as he frequently plays with the signification and legibility of text, so he insists on the constructed character of photographs. His performance photographs flesh out the iconicity of photography as opposed to its indexicality. While such a critique has been issued against documentary photography, Pope.L makes the same point about the images that register as street photographs. In her recent essay on street photography, Terri Weissman ‘challenges the belief that bystanders are “innocent” observers’, a belief popularised by Colin Westerbeck and Joel Meyerowitz in their 1994 book Bystander: A History of Street Photography.34 ‘The bystander is embedded in the image, even if not pictured’, Weissman contends.35 Pope.L’s street performance photographs can direct us to a similar observation.

The photographs of Pope.L’s street performances that record police interventions confront us with the absurd and grotesque, yet they frame these anomalies within systems of power and oppression that are recognisable and real, vacillating uncomfortably between the documentary and the street genre. In a book dedicated to explicating the distinction between the two, Clive Scott proposes that, in contrast with the documentary type, street photography does not fix its subjects, offering a ‘transformative capacity’.36 Street photography, in this reading, is more aleatory, more dependent on the photographer’s chance encounters and keen eye, and therefore less moralistic. ‘If documentary photography draws us towards confrontation, looks to exert a moral pressure, street photography affects the detachment and courts communal irresponsibility in the name of uncontrolled individual responses’, Scott explains.37

In Pope.L’s performance photographs there is a commingling of both modes, which destabilises their theoretical separation. Pope.L’s images are framed like street photography: overcrowded, shot from behind his back, with peripheral figures blocking out focal action. In these frames, the performing artist does not figure as the stereotypical ‘bum’ of documentary photography described by Rosler. Pope.L’s performance persona may approximate the position of a homeless person or a panhandler, but the artist invariably makes it strange and contradictory. At the same time, the reactions to his street actions, whether they come from police officers or passers-by, do not seem strange at all. They are manifestations of the system of racist oppression that is already in place, the system that we are accustomed to, which has become invisible – unless perhaps, as we have seen in numerous acts of police violence against African Americans. The interlacing of street and documentary modes in these photographs, achieved in part by withholding their authorship, invokes some of photography’s most hackneyed tropes – such as the unhoused, inebriated occupants of city streets – but refuses to victimise them, or to make them the central characters in this story.

Instead, through the use of framing, attention is placed on the audience – viewers or potential documentarians who consume the spectacle of vulnerability and oppression and who have the capacity to reproduce it. This melange of photographic genres encapsulates the essential paradox that Pope.L’s performance photographs expose: everyday Black suffering, dispossession and disenfranchisement in the United States are simultaneously spectacularised and dismissed with ruthless regularity. What is most unsettling about the photographs of Pope.L’s street performances is the inescapability and the incessant character of surveillance and oppression in the face of the constant struggle that the artist embodies. While denying Pope.L’s performance persona any fixed or prescribed role known from documentary photography, these images also rule out the possibility of change. Even when no law enforcement officials are in sight, the artist’s body is framed by a system that thwarts any ‘transformative capacity’ he might possess – after all, he keeps on crawling.

Throughout Pope.L’s practice, photography is deployed to literalise the frame, revealing the workings of the system. In one of the most widely reproduced photographs of The Great White Way: 22 miles, 9 years, 1 street FIG. 7, a multi-part crawl that Pope.L performed in a superman costume, the artist’s struggling body is framed within a blue police fence inscribed with the words ‘police line do not cross’. Unlike the photographs discussed above, pedestrians’ faces cannot be seen and their roles in the event remain undecipherable. Like the other photographs, however, this image highlights the incessant policing of Black presence in public space, literalising oppression and violence that continue under our watch. In this image, we are confronted with both the fleeting moment when Pope.L’s performing body becomes physically framed by the police barricade and the ever-present, unchanging oppressive system that remains firmly in place.

Acknowledgments

For their feedback on research undertaken for this article the author would like to thank members of the Modern and Contemporary Research Cluster at the University of St Andrews, and the participants of the College Art Association 2021 Annual Conference and the Association for Art History 2022 Annual Conference. Special thanks go to Catherine Spencer (University of St Andrews) and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw (University of Pennsylvania) for their generous guidance and insights.