Adrian Piper’s ‘Indexical Present’ in the work of Arthur Jafa

by Isabel Parkes • June 2020

In an essay first published in Reimaging America: The Arts of Social Change (1990), the artist and philosopher Adrian Piper used the term ‘indexical present’ to convey a longstanding focus in her art on ‘the concrete, immediate here-and-now’.1 A term derived from linguistics and the philosophy of language, ‘indexicality’ refers to the phenomenon of a sign indicating – indexing – an object in the context in which it occurs. Piper’s concept of the indexical present takes root in the phenomenology of the 1960s avant-garde as well as in the writings of Immanuel Kant and Vedic philosophy.2 Experiencing the indexical present through ‘a confrontative art object’ wrests attention away, Piper writes, ‘from the abstract realm of theoretical obfuscation, and back to the reality of [one’s] actual circumstances at the moment’.3 Decades after Piper (b.1948) articulated the idea, Arthur Jafa (b.1960) employed a related, operative sense of immediacy in his seven-minute film Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016). Composed largely of found footage that describes a cultural construction of Blackness in America, the film both encourages identification with its subjects and antagonises viewers, locating them within a feedback loop of cause and effect. Bringing the concept of the indexical present to bear on an analysis of Jafa’s film reveals the way that Piper and Jafa, despite the different media they employ, each complicate simple markers of difference, finding form in mainstream narratives that allows them to explore their mutual interest in race and representation.

The indexical present in Adrian Piper’s art

In her description of the indexical present, Piper stresses the power of the specific and personal:

Artwork that draws one into a relationship with the other in the indexical present trades easy classification – and hence xenophobia – for a direct and immediate experience of the complexity of the other [. . .] Experiencing the other in the indexical present teaches one how to see.4

For many years – and well before naming the concept of the indexical present – Piper has used perception and subjectivity as material for her socially-orientated art, in particular as a way to confront the intransigence and subtleties of racism.5 In the 1970s and 1980s the United States witnessed the gradual suppression of the Black Power Movement and a growing police presence in cities that – while proclaiming a war on drugs – criminalised poverty and expanded prison populations. In 2019 an unredacted tape of a 1971 phone call between then President Nixon and Californian Governor Ronald Reagan was released by the United States National Archives. The racist content of their conversation, withheld from records for fifty years, exposes a sustained tolerance for racism, condoned and perpetrated at the highest government level. In one section Reagan exclaims, ‘to see those – those monkeys from those African countries’, to a laughing Nixon. He continues, ‘damn them, they’re still uncomfortable wearing shoes!’6 It was under these conditions that Piper developed work that implicated her audiences in the perpetuation of systemic social violence.

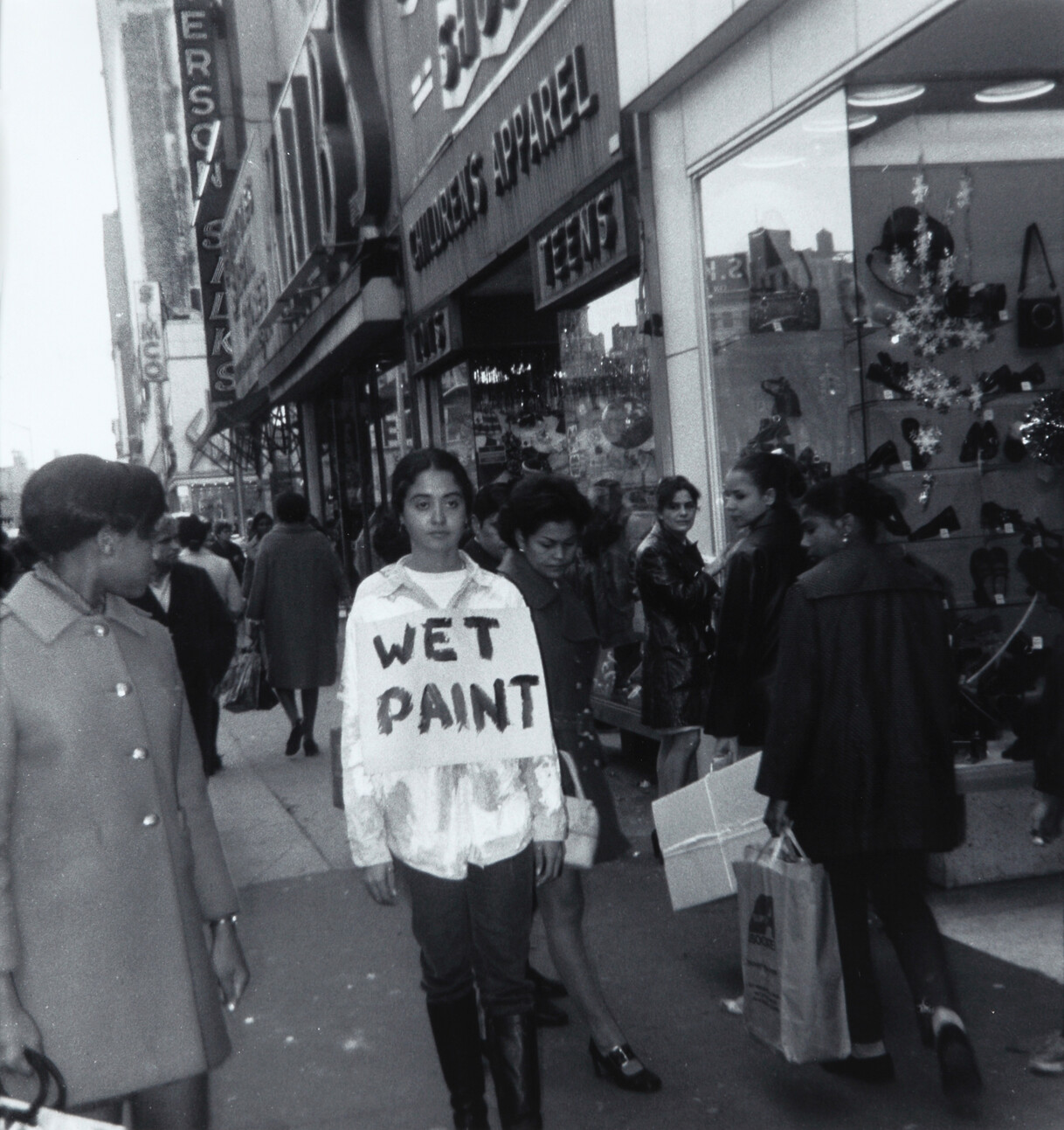

For Catalysis I, the first in a three-year series of performances in public spaces, Piper saturated her clothes in vinegar, milk, cod-liver oil and eggs and donned them for a rush-hour trip on the New York City subway. By activating her body through physical signals and proximity, Piper – a lithe Black woman suddenly emanating an overwhelming stench – forced viewers to become part of the action whether they were smelling, looking or even overlooking her presence.7 As she has described, ‘the immediacy of the artist’s presence as artwork/catalysis confronts the viewer with a broader, more powerful, and more ambiguous situation than discrete forms or objects’.8 The performances formed a series of related public ‘situations’ in which passers-by might have witnessed Piper shopping at a department store in sticky, paint-soaked clothes with a sign reading ‘WET PAINT’ (Catalysis III) FIG. 1 or walking around an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, chewing gum and blowing it into large bubbles that stuck to her face as they popped (Catalysis VII).

Catalysis exposed the illogic of representational norms that maintain difference in everyday life by advancing markers of an individual’s autonomy to an extreme – dressing or smelling against social norms – within plain sight. Understood as an event and situation, each of Piper's Catalysis performances embeds itself in a moment and extends beyond temporal limits, in that the condition it indexes (that of the other) is ongoing. Piper catalyses a reaction – surprise, disgust – that interrupts but does not consume viewers, most of whom ignored her.

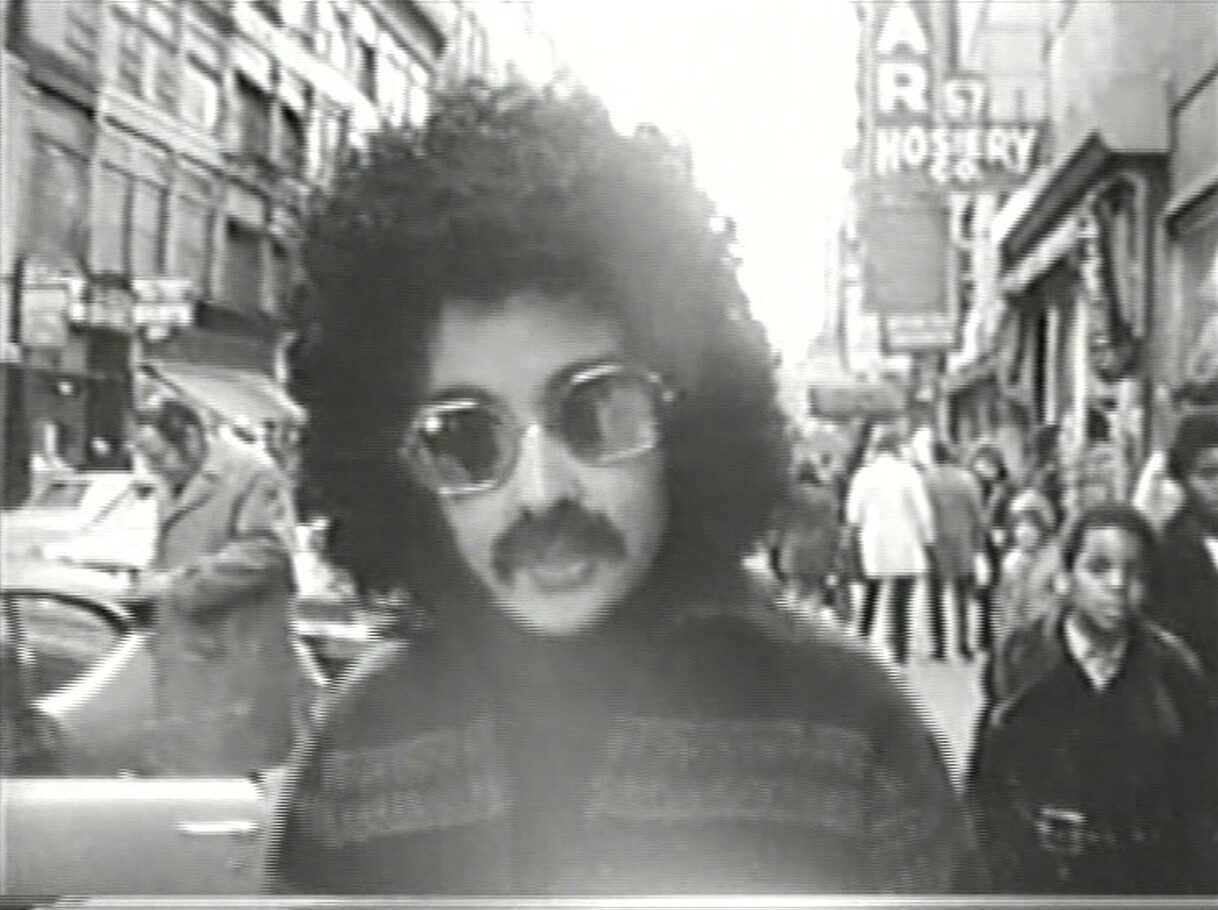

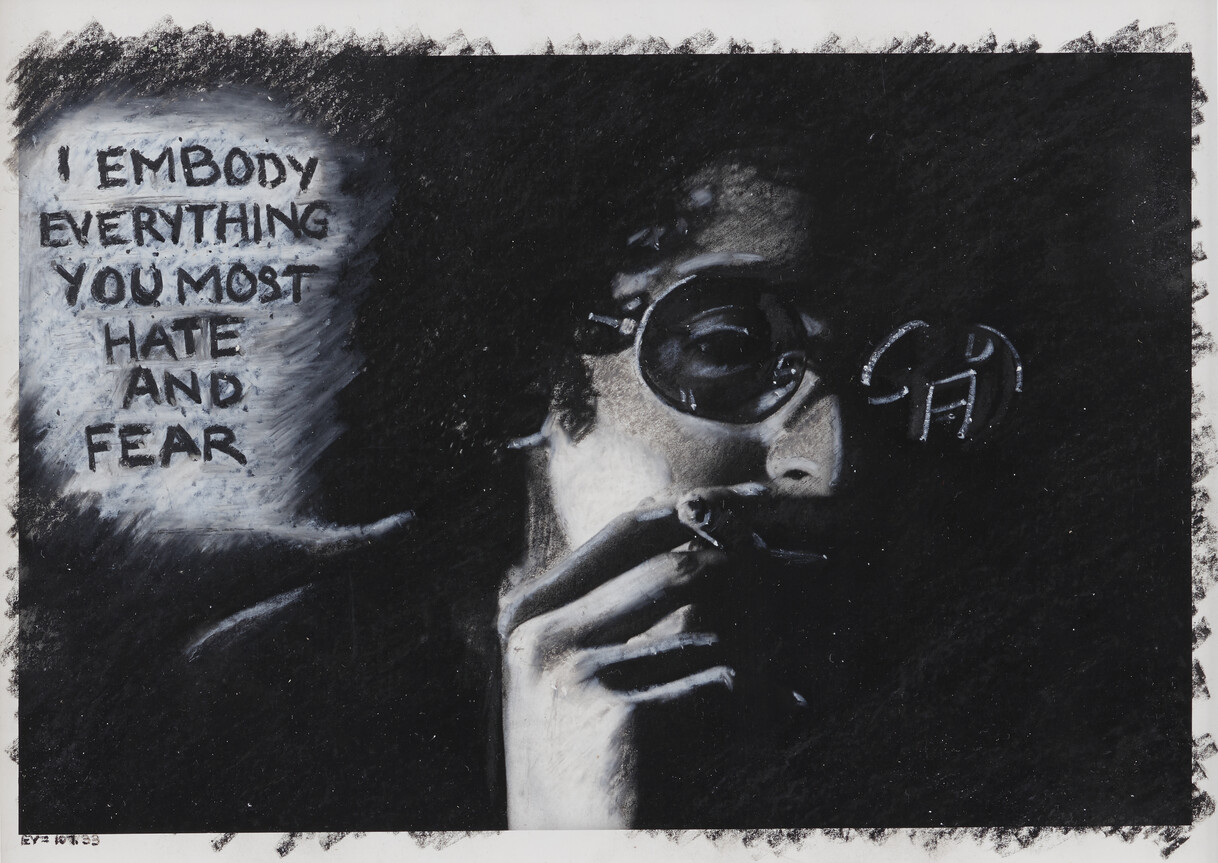

Piper’s Mythic Being series (1972–75), which includes photographs and drawings developed in relation to performances FIG. 2, similarly probes interpersonal boundaries of confrontation. Dressed in a black afro wig, aviator sunglasses and men’s clothing, Piper roamed city streets muttering to herself, adopting an invented persona that might appear to onlookers, especially white ones, as a ‘social threat’.9 She presented her ‘mythic being’ to ‘embody everything you most hate and fear’.10 In both series, Piper was ‘present to difference’, inhabiting an indexical present that exaggerated an experience with the other under cultural conditions of pervasive racial anxiety.11

Connecting Piper and Jafa through the indexical present

It would be an understatement to say that Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death (hereafter Love is the Message) made an impact in the art world. One headline declared that it ‘described America to itself’; e-flux called it ‘shattering’; The New York Times critic Roberta Smith called it ‘a seven-minute-long life changer’; multiple museums rushed to acquire it, and a significant number of international venues have presented it since its premiere.12 In 2018 the Museum of Modern Art, New York, presented a retrospective of Piper’s work that spanned the building’s entire sixth floor (a first for a living artist) and received overwhelmingly positive reviews.13 In examining a concept and strategy that incites close consideration of one’s response to a work, reflecting on both Jafa and Piper’s present popularity – overdue and well warranted – nonetheless becomes a vital part of writing about the indexical present in 2020.

Jafa and Piper operate not at the margins, to which bell hooks pointed as sites of resistance, but at the very centre.14 Their work offers an elastic yet particular interpretation of race, which, as Thelma Golden writes in her introduction to the catalogue for Freestyle, a 2001 exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem, ‘embrace[s] and reject[s] the notion of [Black art] at the very same time’.15 In the same text, Golden describes how she and the artist Glenn Ligon began using the term ‘post-black’ to characterise ‘artists who were adamant about not being labeled as ‘black’ artists, though their work was steeped, in fact deeply interested, in redefining complex notions of Blackness’. This concept, although generative in nuancing discussions of race in visual art, is less useful as a point of comparison between Jafa and Piper than the more recent writing of critical theorists such as Margo Natalie Crawford, Greg Tate and Touré, who move ‘from exhaustive Blackness to expansive Blackness’, seeking a territory and temporality without a fixed beginning or end.16 Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson have drawn attention to the art-historical tendency to see an artist’s work as a response to social or political conditions rather than a catalyst for them, particularly where artists of colour are concerned, ‘since they often face the possibility that their work will be instrumentalised as an unmediated reflection of ‘black life’ (particularly in moments when white liberal identity is in crisis!)’.17

Although expressions of and attitudes towards Blackness are central to the works discussed here, Piper’s indexical present is not inherently tied to questions of race. Rather, it is a tool for exploring the ways in which social interaction informs self-definition, rejecting consensus and scale in favour of discord and specificity. It allows both Jafa and Piper to break down clear separations between art and reality, me and you, to mark how and where these notions intersect. The resulting assertions of subjectivity implicate audiences not simply as participants but as actors in the perpetuation of everyday social violence. While Jafa’s montage of moving images reads race politics through events circulated in the media, it seems that Piper’s approach is fundamentally ontological, interrogating both the nature of and processes through which ideas are brought into being. The indexical present remains an expansive site of intergenerational transmission that helps frame how the representation of racial inequality and racial violence has – or has not – shifted.

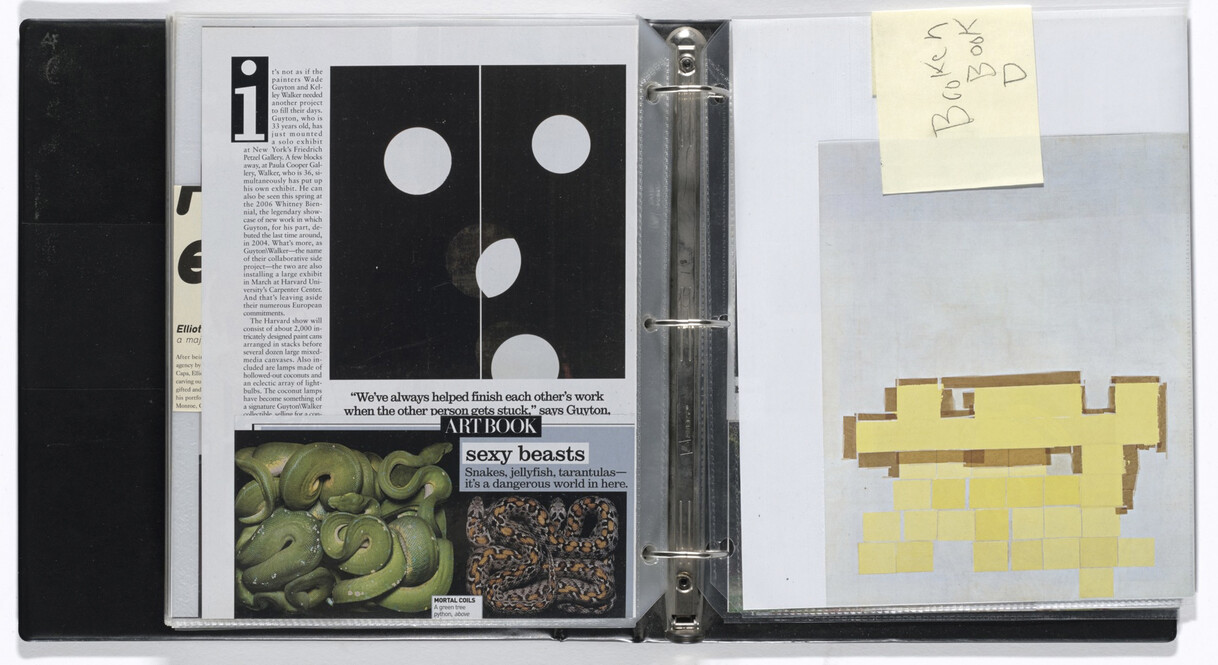

Arthus Jafa's ring binders (Untitled Notebooks, 1990–2007)

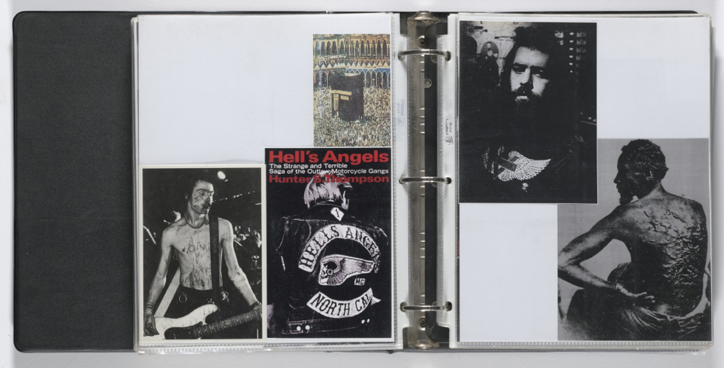

Twenty-five years before Jafa made Love is the Message he worked as a cinematographer on Julie Dash’s feature film Daughters of the Dust (1991). Part of his process involved collating images, clipped from diverse sources, into the plastic sleeves of three-ring binders (Untitled Notebooks, 1990–2007). What began as a mobile mood board evolved into a living archive, which, particularly alongside Love is the Message, demonstrates how Jafa has for decades constructed a ‘specific’ visual culture that grounds his indexical present in individuality and autonomy as markers of subjecthood. The combinations of images in his binders are personal and conceptual, intuitive and aesthetic, disturbing and revealing.

Looking at the binders offers an unheimlich experience of an unknown yet familiar ‘other’, which we might relate to Piper’s assertion that, ‘experiencing the other in the indexical present teaches one how to see’.18 Images that in their content or style might date to a particular era or mood are complicated by those which interrupt their temporality or meaning. In one spread, Jafa places an album release announcement for Snoop Dogg’s The Blue Carpet Treatment opposite an image of two people seated on the floor, facing a bright screen in a room flooded with blue light. Many pages are comprised of multiple images, for example Mecca’s Kaaba above a Hunter S. Thompson book cover next to a punk, across from a portrait of Charles Manson and an image known as the ‘The Scourged Back’ FIG. 3. Some images are readily identifiable while others present exercises in pareidolia FIG. 4. Photographs of a dark shape or hanging sculpture urge viewers to interpret meaning without context. In these moments, the binders’ individual images as much as their juxtapositions – the relation of one to the other and the space between them – create Rorschach tests. As Piper explained in an interview, ‘Racism is a visual pathology, feeding on sociological characteristics and so-called racial groupings only by interference and conceptual presupposition. Primarily it is an anxiety response to the perceived difference of visually unfamiliar ‘other’.19 With their overriding sense of visual and conceptual Blackness, Jafa’s binders invoke the means through which difference is read onto and sublimated into the everyday.

‘Something is wrong here’

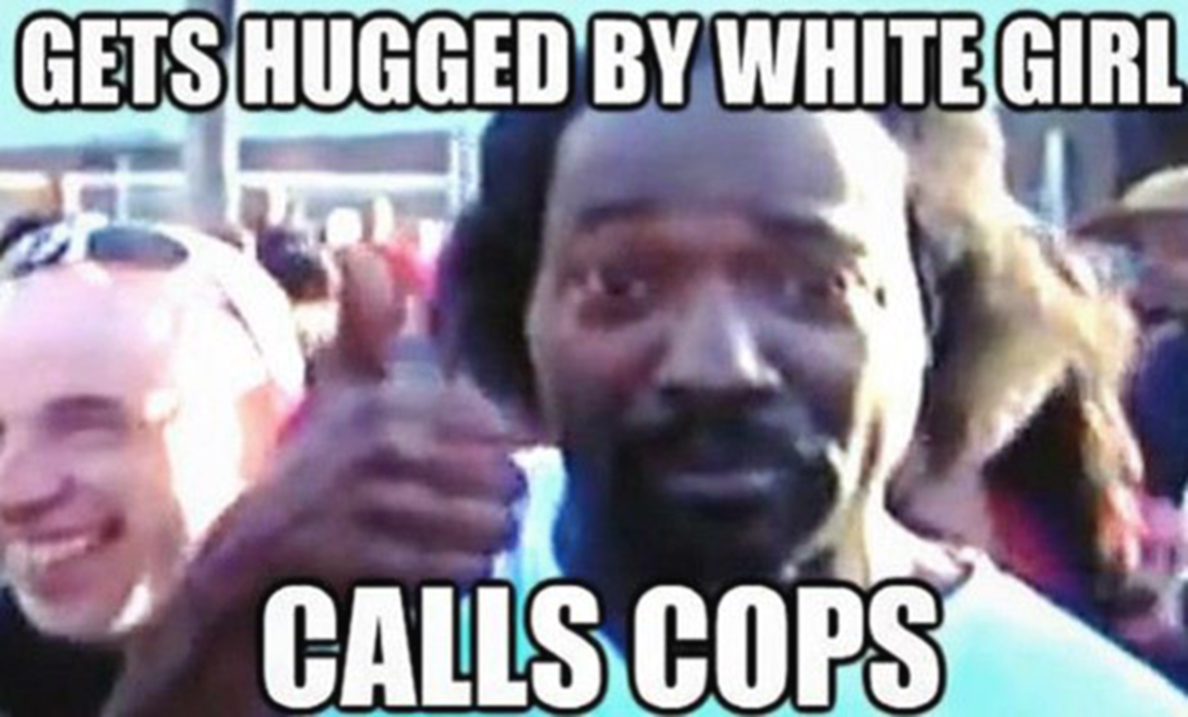

Love is the Message begins with a Black man describing to a reporter how he rescued a woman from a decade of captivity in his neighbour’s cellar: ‘I knew something was wrong when a little pretty white girl ran into a black man’s arms’ FIG. 5. He adds emphatically, ‘Something is wrong here. Dead giveaway’. Some viewers may recognise the scene from its viral circulation on the internet in 2013. Picked up from local news sources and remixed into memes FIG. 6 and auto-tuned songs that were viewed online over ten million times, the speaker, Charles Ramsey quickly went from hero to internet minstrel, repeated on loop for his dishevelled, ‘down home’ appearance and ‘hilarious’ delivery.20 In opening his video with this clip, Jafa acknowledges its persistent place in popular culture as much as the problem of its popularity.

Over the course of the video’s seven and a half minutes, a slowed-down version of Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam – an anthemic, gospel-inspired hip hop declaration of the singer’s faith in God from 2016 – swells and fades. Ramsey’s scene cuts to a packed gym at a Howard University basketball game, its bleachers filled with crowds of young Black students dancing from side to side in a unified motion called ‘swag surf’. Other clips follow: the widow of Fred Hampton, a charismatic Black Panther, marching on the day after her husband’s assassination in 1969; a young man dancing with a plastic red pistol in his hand; a police officer shooting and killing Walter Scott in 2015; a couple dancing; the feminist scholar Hortense Spillers FIG. 7; Angela Davis’s fading smile; Caribbean-American entertainer Bert Williams performing in blackface FIG. 8; Beyoncé dancing.

Later in the sequence, the music lowers in time for viewers to hear a Black woman describe her escape from a fire that destroyed her apartment block in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Like Ramsey, Michelle Dobyne became an internet celebrity overnight. She speaks energetically to a reporter:

‘Something ain't right!’ I said, ‘Aw, man! She said, ‘Aw, man, the building is on fire!’ I said, ‘Nah, what?’ I got my kids, and we bounced out. Uh, uh. We ain't gonna be in no fire! Not today!

The next scene shows a building engulfed in flames, partially covered by the logo for Getty Images. Looped and projected onto a large screen that renders its subjects life-size and surrounded by booming speakers, Love is the Message is experienced by viewers as a hallucinatory cycle of images, light and music that is both crystal clear and disorienting. Jafa creates disruptive, affective moments of watching by juxtaposing unfamiliar, often violent images with instantly recognisable shots of Black icons who can be said to have survived various kinds of extremity: Obama or Beyoncé, for example. These individuals are not themselves markers of violence, but their juxtaposition with images of a Black man being dragged across asphalt or Black protestors being knocked down by a water canon suggests that Black success remains tempered by suffering.

Non-consensual indexical presents

Unlike Jafa’s video, which was first shown at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, Adrian Piper’s conception of the indexical present, considered here first in Catalysis and Mythic Being, initially found form outside of art institutions.21 This reflects the artists’ different media – moving image and performance – as well as fast-changing patterns of cultural consumption in the art world. Piper’s implementation of the indexical present in her performances is both conversational and confrontational, discursive and declarative. This multivalent approach is also evident in her static work. For example, in The Mythic Being: I Embody Everything You Most Hate and Fear FIG. 9, a monochromatic, drawn on photograph, the figure’s speech bubble declares, ‘I embody everything you most hate and fear’, the effect of which is felt fully only if and when the ‘I’ (the Mythic Being, a Black man) finds ‘you’ (the viewer). In this and other works, we can interpret that the existence of the art itself is substantiated through context and fulfilled by a viewer’s physical engagement with it.

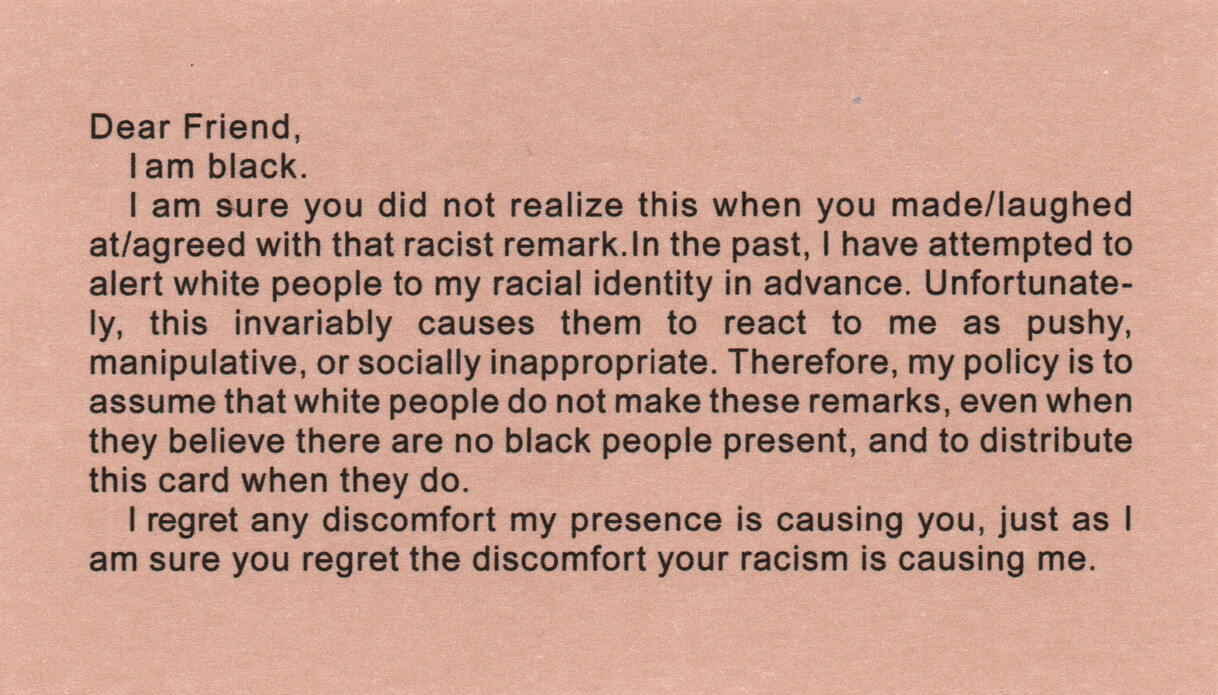

Since 1986, Piper has created and handed out ‘Calling Cards’, printed messages on brown and white paper cut to the size of a business card. In the example of My Calling (Card) #1 FIG. 10, the ‘reactive guerilla performance’ allows her to address people’s racist remarks in the moment of their articulation and in doing so generate the indexical present. Writing in 1990, Piper describes dinners or cocktail parties at which she, appearing to some as white, would become the object of or witness to racist remarks.22 In her notes, she lists possible reactions to these situations, ranging from saying nothing, to reprimanding the offender, and presenting her My Calling (Card) #1 as the eighth and final option. Without interrupting the affect of the social scene, the courteous language of Piper’s My Calling (Card) #1 mirrors the veiled propriety of its context: ‘Dear Friend, / I am black. I am sure you did not realise this when you made/laughed at/agreed with that racist remark [. . .]’. However briefly, Piper’s too-courteous ‘I am sure you did not realise this’ distances viewers from what she appears to insinuate are learned (not innate) attitudes and behaviours, and instead brings them ‘into direct, unmediated, and focused relationship with one of the most discomforting “objects of perception” for white people: African Americans’.23

At the same time, My Calling (Card) #1 can be said to enact a two-way interpersonal exchange in a single moment. It asks its recipient ‘to think about the potential of his or her words to hurt, to alienate, to violate’ but, as Piper told an audience member at a 1987 talk at a Chicago gallery, handing out one of the cards, also ‘ruin[s] [her own] evening’.24 Maurice Berger, recalling the talk, wrote that ‘it is at this moment that Piper has achieved a true and profound indexical present – an instant when each person in the room is caught off-guard, compelled to jettison preconceptions and ask difficult, even painful questions about themselves’.25 Piper’s card allows her to take hold of a situation in which she is being subjugated. It asserts her autonomy and subjectivity and makes plain the internalised dynamics through which othering occurs. The resulting situation becomes a site of possibility, then, with Piper as object and subject – and viewer as subject and participant – each revealing how individuals might move through and beyond the restrictive assumptions of others.

Around four minutes into Love is the Message the actress Amandla Stenberg, shown for a few seconds against a plain background, looks at the camera and asks: ‘What would America be like if we loved Black people as much as we love Black culture?’ FIG. 11 Stenberg’s direct address disrupts the viewer’s distance from the situations depicted on-screen, alerting them to the choices ‘we’ make to participate in aesthetic experiences that link to broader cultural and political conditions. As when Piper hands out My Calling Card #1, Stenberg forces a real-time recognition by viewers that they are participants: the consumption of Black culture is not separate from systemic violence. In fact, both are products of a society that exceptionalises and pathologises Blackness. You, we – are the link between them.

Although arresting, Stenberg’s address in Love is the Message is less direct than Piper’s, which gives viewers (as participants in) a concrete, card-shaped understanding that ‘racism is not an abstract, distant problem [. . .] It begins between you and me, right here and now, in the indexical present’.26 When Jafa edits footage of Drake playing a concert or Serena Williams crip-walking on a tennis court FIG. 12 – clips he takes from mainstream culture and links sonically with Ultralight Beam – the feeling of being there, swept up in the scenes’ energy, carries ebulliently over to the adjacent scene, which shows a police officer placing a bikini-clad Black teenaged-girl at a block party in a chokehold FIG. 13. But viewers (as spectators) can rationalise how one scene is permissible and the other not, shake heads in disbelief, and continue watching. They can applaud Jafa’s deft combination of scenes of violence against Black people with those that attest to Black excellence and exit the gallery without accounting for their own historical conditioning to expect and accept certain stereotypes. They remain consumers, possibly more woke to the struggles of their fellow citizens yet likely unaware of the degree to which they have internalised quotidian violence. Piper, by contrast, contends directly with what she has called the ‘Who, me?’ syndrome that infects the ‘highly select and sophisticated audience that typically views [her] work’ and that, more explicitly, collapses distinctions between viewers and subject.27 My Calling Card #1 creates an indexical present that opens up the self and requires a response from the other.28 There is no place from which either she as artist or the addressee as recipient-participant can observe the situation theoretically.

Love is the Message challenges viewers to understand race through the circulation of media imagery in a present ‘reality’ of a multisensory gallery experience. Piper’s indexical present instead stages the here and now through pronouncements that mark and then transcend arbitrary boundaries of social understanding. The idea of the indexical present is therefore delineated between addressing a here and now that implicates its audience, with Piper, and history in the present, with Jafa, that instructs. Each artist’s engagement with notions of ‘reality’ helps to further elucidate this distinction.

Representing and misrepresenting reality

Like many of his contemporaries, who experienced how little evidence served Rodney King in his trial against the LAPD (or more recently, Ahmaud Arbery and many other Black Americans and their families), Jafa mistrusts popular notions of factual or consensual reality. While he leaves logos of many of his sources on-screen, employs handheld, shaky camera footage and jump cuts to convey a sense of the evidentiary in Love is the Message, Jafa also privileges a version of reality that is fragmentary, literally collaged with varying perspectives. He uses documentary techniques as a foil against popular representations and stereotypes of Blackness to illustrate how one influences the other.29 Through juxtaposition and edits of familiar footage, Jafa’s film can be said – to quote Piper – ‘[trade] easy classification [. . .] for a direct and immediate experience of the complexity of the other’.4 In combination, Jafa’s layering of styles, genres and filmic techniques in Love is the Message exposes the relative and mutable truth of ‘reality’ and the importance of one’s position within its matrix.

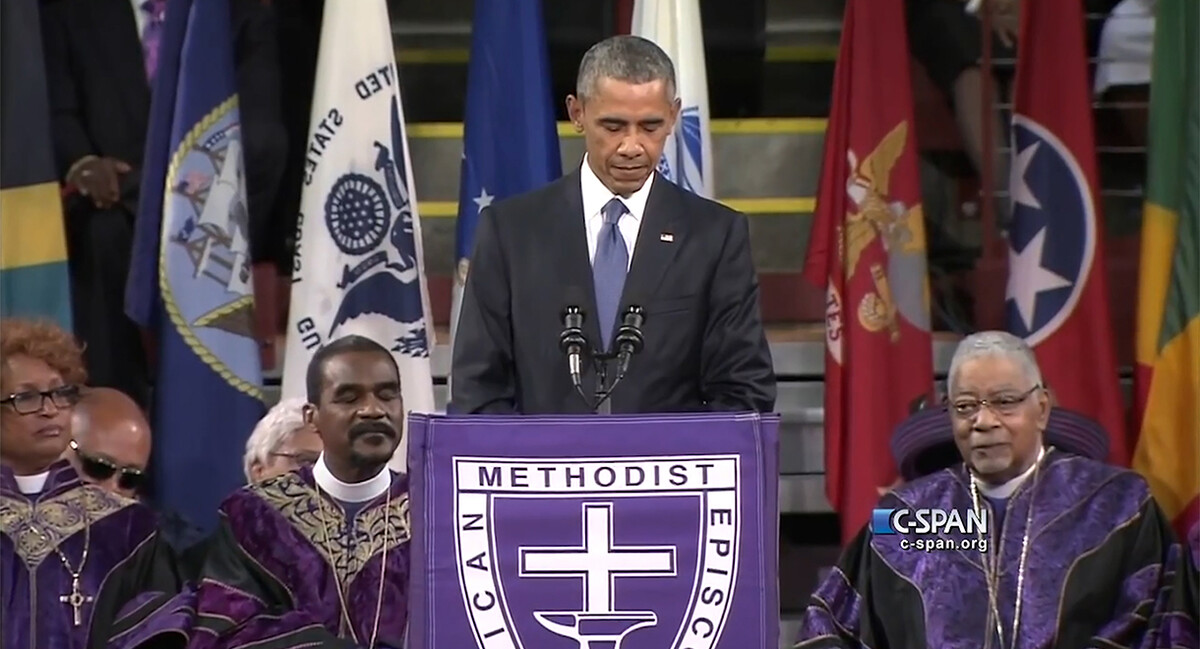

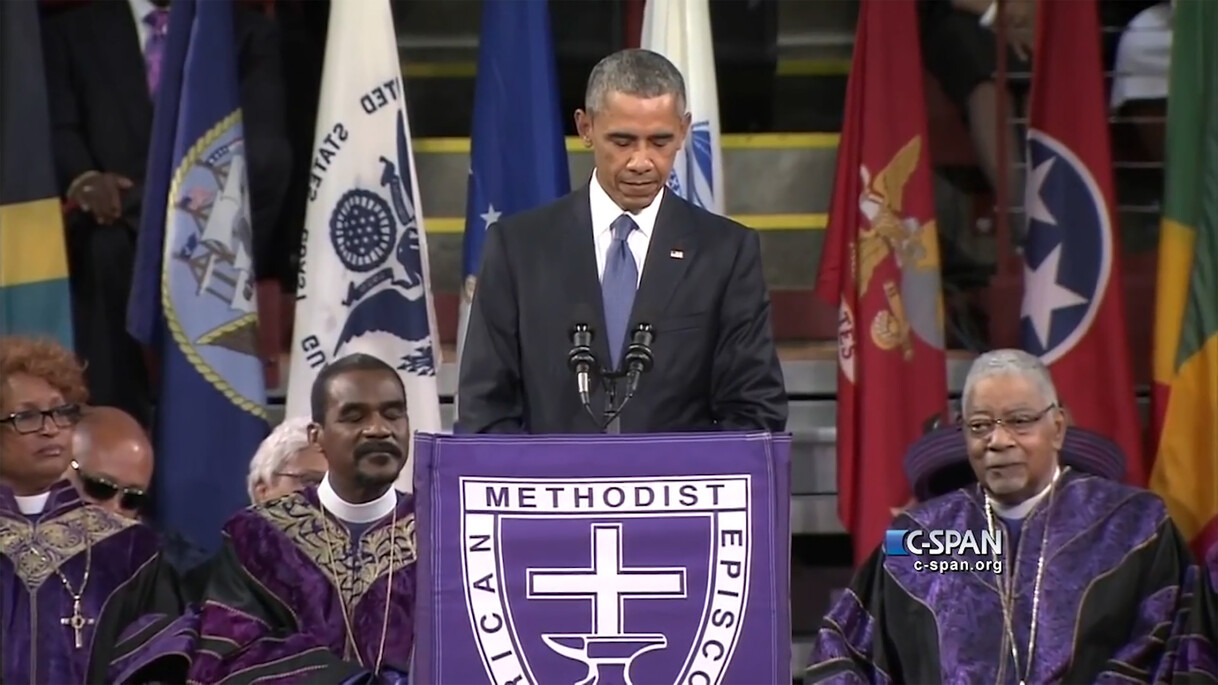

A viral clip of then-outgoing President Barack Obama singing the opening lines of Amazing Grace while delivering a eulogy for Reverend Clementa Pinckney FIG. 14 is followed by a black-and-white film clip of a white man walking down an aisle with his hands on both shoulders of a young Black boy. Man and boy are surrounded on both sides by rows of white onlookers. Jafa jump cuts to Obama at the podium, beginning to sing. Four Black mourners seated on the stage behind him glance at each other, around the venue, and at Obama in varying states of delight and disbelief. One stands up and a the film cuts to the earlier black-and-white source, which shows a white man extending his arms over a podium and beginning to speak FIG. 15. Two Black men seated at his left stare at something off-screen. In a sequence that lasts a matter of seconds and relies heavily on touch and sight lines between Black and white bodies, Jafa positions ‘real’ footage (stamped with the C-Span logo) alongside clips drawn from cinematic history in what he has termed ‘affective proximity’ in order to convey ambivalence about the president.31

As the film theorists Robert Stam and Louise Spence point out, such positive, emotionally persuasive images as this footage of the President ‘obscures the fact that “nice” images might be at times be as pernicious as overtly degrading ones, providing a bourgeois façade for paternalism, a more pervasive racism’.32 Obama appears in Jafa’s film, framed by whiteness as a symbol of both ‘real’ Black joy and of the persistent inability of Blackness to exist on its own terms.33 Love is the Message can be said to address ‘real’ Black life only in so far as it exposes it as a tenuous and biased co-creation of observer and observed. Rather than try to define a standard of Blackness, which itself becomes a kind of tyranny, Jafa, like Piper, exposes the notion’s plasticity and the importance of one’s position within a given system of representation.

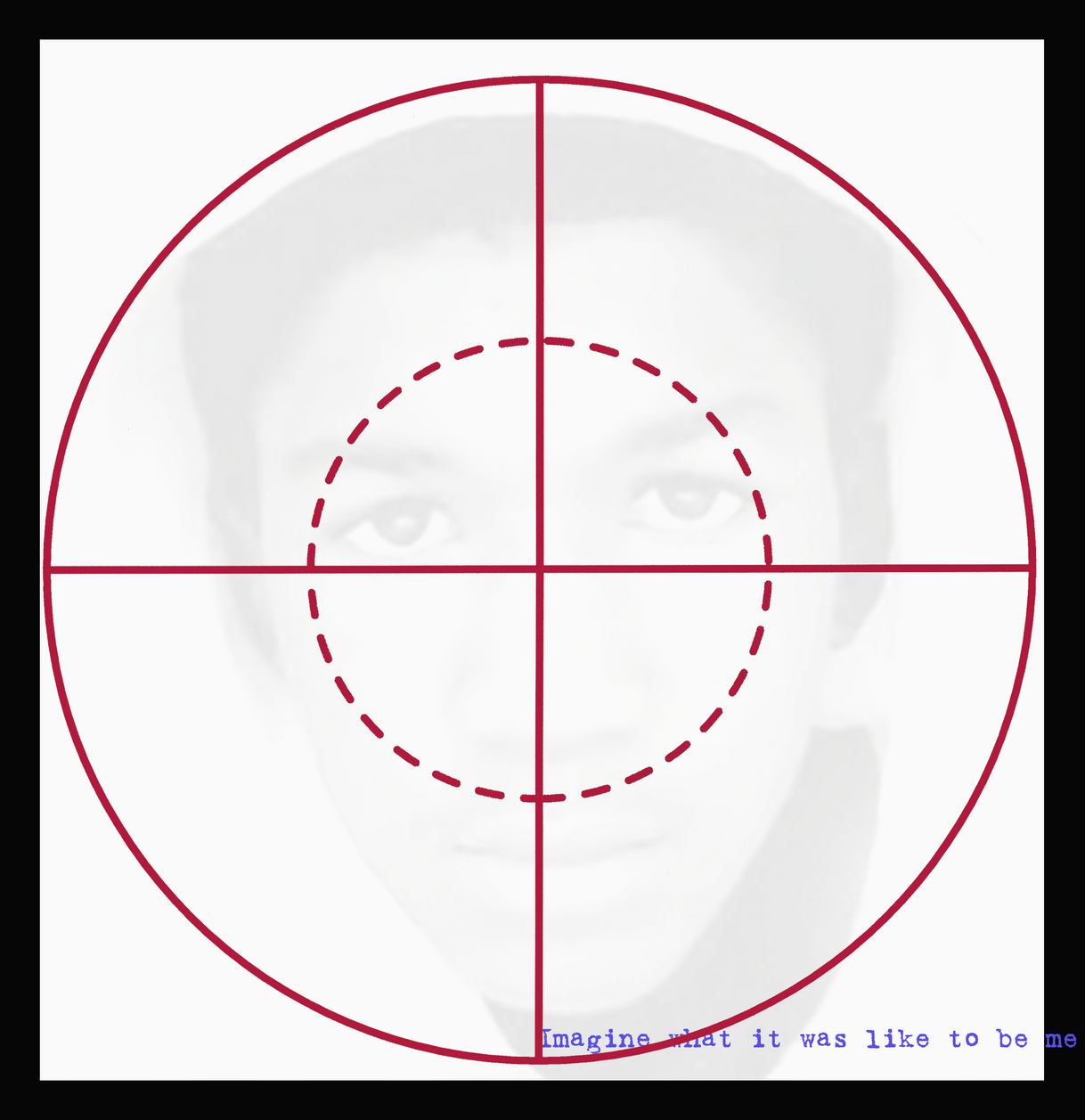

In 2013 Adrian Piper released Imagine [Trayvon Martin], a free PDF download of a faint, black-and-white image of Trayvon Martin, a seventeen-year-old Black teenager who was fatally shot in the chest by police officer George Zimmerman in 2012, encircled by a red bulls-eye FIG. 16. The image is framed with a thick black line and in the lower right-hand corner purple script reads, ‘Imagine what it was like to be me’. The written word ‘imagine’ presents an invitation to position oneself in relation to the act of killing a Black teen (Zimmerman claimed self-defense and was not charged at the time; in 2013 he was tried for manslaughter and acquitted by a jury). The indexical present here emerges from a lived ‘rage in response to the killing of Black youth [and] demands a temporal break with the past’.34 Imagine [Trayvon Martin] does not try to reason people out of being racists or xenophobes, but instead shocks their interpretative systems, so that the ‘damaging and maladaptive relationships between images, words, and the beings they represent might be jostled apart, and the rational and beneficial ones reconstituted’.35 Imagine [Trayvon Martin] derives further effectiveness from appearing as art object and, in a ‘pincer movement’, piercing through abstraction to reveal the ways sight lines and representation coincide with issues of life and death.36

In a section of her Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto not quoted by Jafa in his film, the artist Martine Syms emphasises the emotional, subjective quality of reality: ‘Since “fact” and “science” have been used throughout history to serve white supremacy, we will focus on an emotionally true, vernacular reality’.37 Jafa relies on emotionality as much as aesthetic comparison and contradiction to index a present that is viscerally complex. Describing how he seeks a technical as much as an expressive possibility in film that might ‘carry the weight and sheer tonality [of] Black song’, Jafa clarified, ‘I’m not talking about the lyrics that Aretha Franklin sang. I’m talking about how she sang them’.38 Through rapid sequences that link documentary footage of Watts (1965) to Ferguson (2016) and Birmingham (1963), Jafa emphasises the persistent and penetrating nature of violence that defines these landmark protests. Interspersing Love is the Message with images of musicians including Aretha Franklin, Lauryn Hill and Miles Davis, Jafa relies on them as positive visual cues as much as the notion that as icons they have evolved from the ‘expressions, desires and pressures of what it means to be black’.39

Given the film’s critical acclaim, Jafa’s awareness of how strategies for Black individuation are co-opted by a mainstream culture that prizes authenticity has generated tension for him. He explained in a 2018 interview:

I’m not making any more Love is the Messages [. . .] I started to feel like I was giving people this sort of microwave epiphany about Blackness. After so many ‘I cried. I crieds’, well, is that the measure of having processed it in a constructive way? I’m not sure it is.40

He reiterated the importance of the nuance of the work, relying, as he has done before, on musical language:

This is why I talk about listening to images and why we’ve called this event a listening session. Listening to images is about allowing yourself to be accessible to the affects produced in all these different encounters.41

Through the work’s emotional appeal as much as its reflection on the dizzying effects of emotion, Love is the Message proposes a two-way process of perception, on the one hand ‘[describing] America to itself’ and on the other, letting America find itself in its images.42 As Piper wrote and has exhibited scrupulously in her own work – ‘racism is not an abstract, distant problem that affects all those poor, unfortunate other people out there. It begins between you and me, right here and now, in the indexical present’.26

Keeping things present and ‘staying in the problem’

The indexical present is a powerful, life-affirming tool that proposes not to change people but to present them with the concrete experiences that might lead them to change themselves. At its core, it is an optimistic, consciousness-raising exercise, influenced equally by intellectual thought and spiritual practice. Speaking at a conference in Mumbai in the late 1980s, Piper explained

To have an immediate relationship with anything is almost impossible, because we have all our conditioning, we have internalized certain stereotypes, belief systems, expectations about the world in general, about the way objects are going to behave, about the way objects are [. . .] So the phenomenon of having to move through and beyond the mediated consciousness of limiting categories and assumptions and expectations that separate us from the state of ultimate realization and self-realization is perfectly general.44

In Catalysis, Mythic Being, My Calling (Card) #1 and Imagine [Trayvon Martin], Piper can be seen to create an indexical present that insists on a here-and-now, incriminating and surprising viewers by exposing not the unknown or unfamiliar, but the too-close and conveniently forgotten. She breaks down the boundary between art and the complex reality it seeks to represent, as well as the way a ‘passive’ viewer is an active participant in both.

Framing Love is the Message in relation to Piper’s use of the indexical present highlights how the film seeks to create an environment in which the audience must confront not only ‘fictive others’ but also ‘their shadow-selves’.45 In his interweaving of borrowed and original, Jafa presents complexity by means of contemporary and historical images that are ‘simplified’ and that frequently serve in the reduction of Black identity. Although this strategy aims to grasp racism in the moment – the image, scene, feeling – in which it occurs, alongside Piper’s œuvre it could be seen to relieve viewers of a responsibility to acknowledge their own participation systems of discrimination. Piper’s work thus foregrounds the ways one might think critically about forms of viewing, literally and figuratively, a point acknowledged by Jafa in his statement to ‘not make any more Love is the Messages’.

At a moment in which nationalist discourse has reached a state of ‘feverish paranoia’ and both the art industry and the institutions that uphold it have paused, a means of identifying the axes at which difference is codified – individually, culturally and politically – feels more urgent than ever.46 Piper and Jafa both keep things present, and as Darby English has written, ‘[stay] in the problem, precisely by forcing [people] to deal with their instability’.47 Although distinct, their respective uses of the indexical present emphasise something familiar and still shocking, redistributing viewers’ sense of time and place. It is not a ‘microwave epiphany’ but perhaps even the opposite, a moment of, as Piper has said ‘deep blankness’.48 In this, an instant of ‘temporarily arrested cognitive functioning’, it offers access ‘to the hidden reality of the strange and unfamiliar things’ often suppressed or ignored in daily life.49 The indexical present allows both Jafa and Piper to reintroduce complexity to a system of representation that objectifies and reduces otherness, and crucially, positions us within it.