Categories and contemporaries: African artists at the Slade School of Fine Art (c.1945–65)

by Gabriella Nugent • November 2022

Introduction

Artists from all over the world studied at the Slade School of Fine Art, London, but the categories of art history and the organisation of museums have rarely allowed them to be studied, taught or exhibited alongside each other. Their separation and dissociation can be attributed to art history’s strong attachment to national narratives. The nation state has operated as the epistemological framework through which artists are grouped and works of art are examined. Even as the ‘global turn’ has sought to combat the Eurocentric assumptions of modernism, it has often perpetuated the discipline’s methodological nationalism, obscuring the cosmopolitan networks to which artists belonged.1 These national narratives contribute to larger continental frameworks that exacerbate divisions between artists who often sat side by side together in the same classroom.

The Slade was an important site of convergence for many African artists central to modern art movements tied to decolonisation between 1945 and 1965. With the aim of proposing new ways of writing histories of modernisms, Liz Bruchet and Ming Tiampo have conceived of the Slade as a contrapuntal node that connects multiple people and histories.2 From its establishment within University College London (UCL) in 1871, the Slade admitted students to its programme regardless of gender, race or religious belief, an attitude in direct opposition to the racial supremacism of British colonial ideology. In comparison to artists who were born and trained in Europe, African artists from British colonies who studied at the Slade were compelled to know multiple worlds, often working between Africa, Europe and North America. However, the categories of art history have not been designed for the capacious lives led by these artists, or indeed the entanglements wrought by colonialism. The discipline tends to marginalise transnational experiences, preferring, especially in the case of African artists, essentialised notions of identity premised on difference.3 These artists are often separated out from their peers and placed in continental isolation. This isolation can be traced back to the emergence of the category of ‘African art’ in the late nineteenth century when objects of ritual or ceremonial purpose entered the European market. Their artistic forms were subsequently adopted by modernist painters, leading to the prominence of ‘African art’ in the Western world. The construction of ‘African art’ was mobilised thereafter to group together artists from across the continent, even if they were operating in Europe or North America. The study of these works of art, otherwise known as the field of ‘African art history’, was largely the purview of anthropologists and gallery professionals, and for a long time it was performed outside the realm of art history proper.

Bearing this past in mind, art history has had much to answer for in recent years, from calls to address the legacies of slavery and colonialism prompted by such movements as Rhodes Must Fall and Black Lives Matter to concomitant surveys of decolonisation published in some of the discipline’s foremost journals.4 However, the demand to expand art history beyond its Eurocentric matrix has largely taken an ‘additive’ approach – new classes, new textbooks and new hires – rather than an essential integration of what was once deemed periphery to a mainstream art history. Bringing together unpublished archival material from UCL Special Collections, London, and works of art from the UCL Art Museum, London, and other collections based in the United Kingdom and abroad, this article proposes a new methodological framework that situates the selected artists alongside their contemporaries, challenging the categories and interpretative frames that have been imposed onto their work. It seeks to demonstrate the entanglement of modern art movements globally by examining the works of art and correspondence of such artists as Ben Enwonwu, Ibrahim El-Salahi, Sam Joseph Ntiro, Paula Rego, Patricia Gerrard, Margaret J. Rees Menhat Helmy, Michael Tyzack and Amir Nour.

Before, during and after the Slade

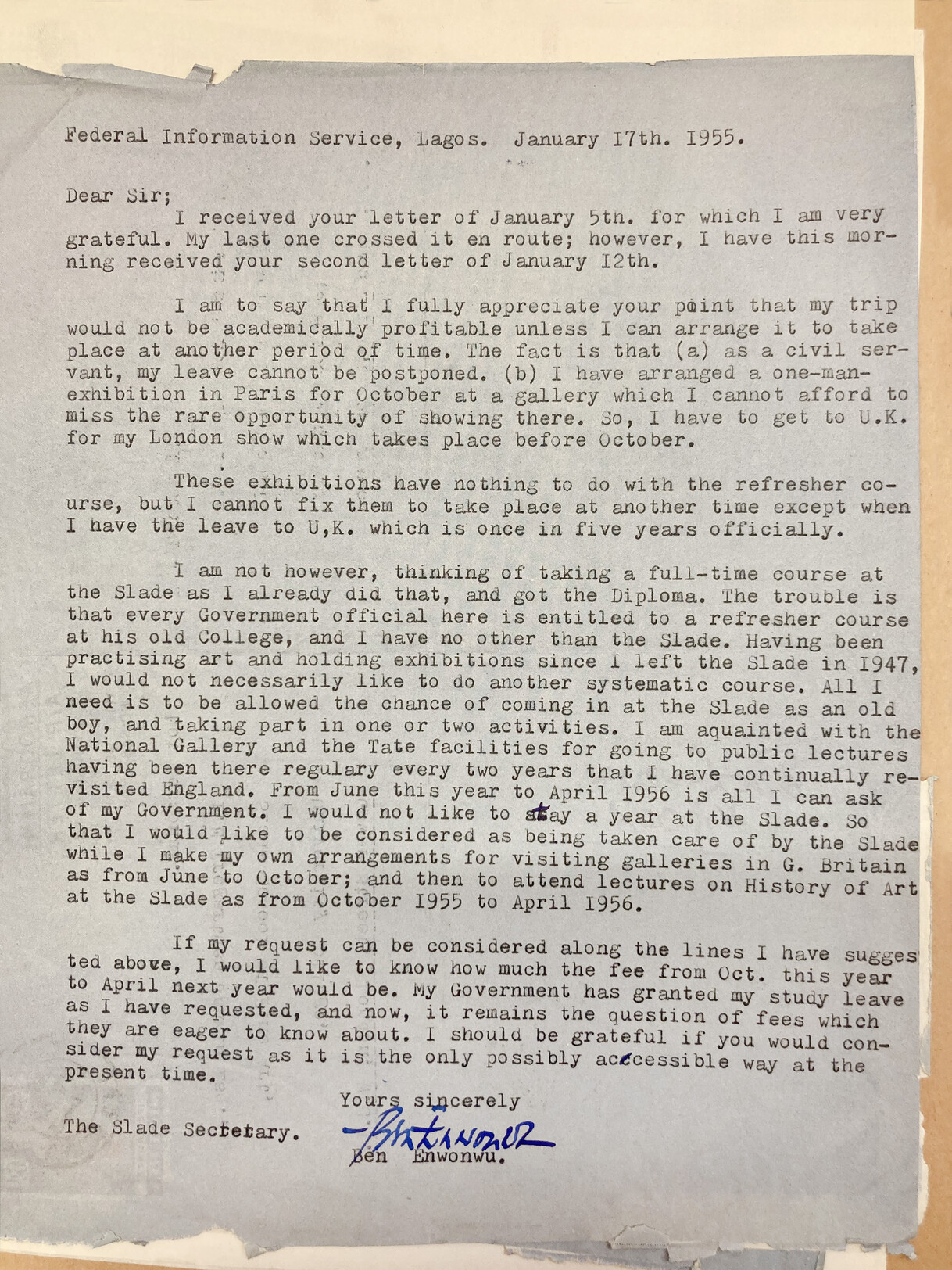

In January 1955 the Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu (1917–94), who had received a Fine Arts Diploma from the Slade in 1947, petitioned the school’s secretary, I.E. Tregarthen Jenkin (1920–2004), for a refresher course FIG. 1. He wrote: ‘Every Government official here is entitled to a refresher course at his old College, and I have no other than the Slade’. This request does not suggest that Enwonwu so relished his time at the Slade that he wished to repeat his education. As detailed by Bruchet and Tiampo in their discussion of the pedagogy at the Slade, the curriculum that Enwonwu was taught was based on a Beaux-Arts model, which followed a progression from drawing Antique plaster casts to life drawing, before taking up painting and sculpture at more advanced levels.5 This methodology stressed the superiority of European models of artmaking, both visually and ideologically, and left little space for other modes of representation. Enwonwu’s response to this curriculum was one of rejection, emphasising the status of the Slade as a contact zone between imperialism and decolonisation. Enwonwu even supplemented his Slade degree with a postgraduate year studying West African ethnography at UCL.6 He also later repudiated the Slade’s intervention into the Nigerian art school system in 1958, when Coldstream was consulted regarding the development of art institutions in the country.7

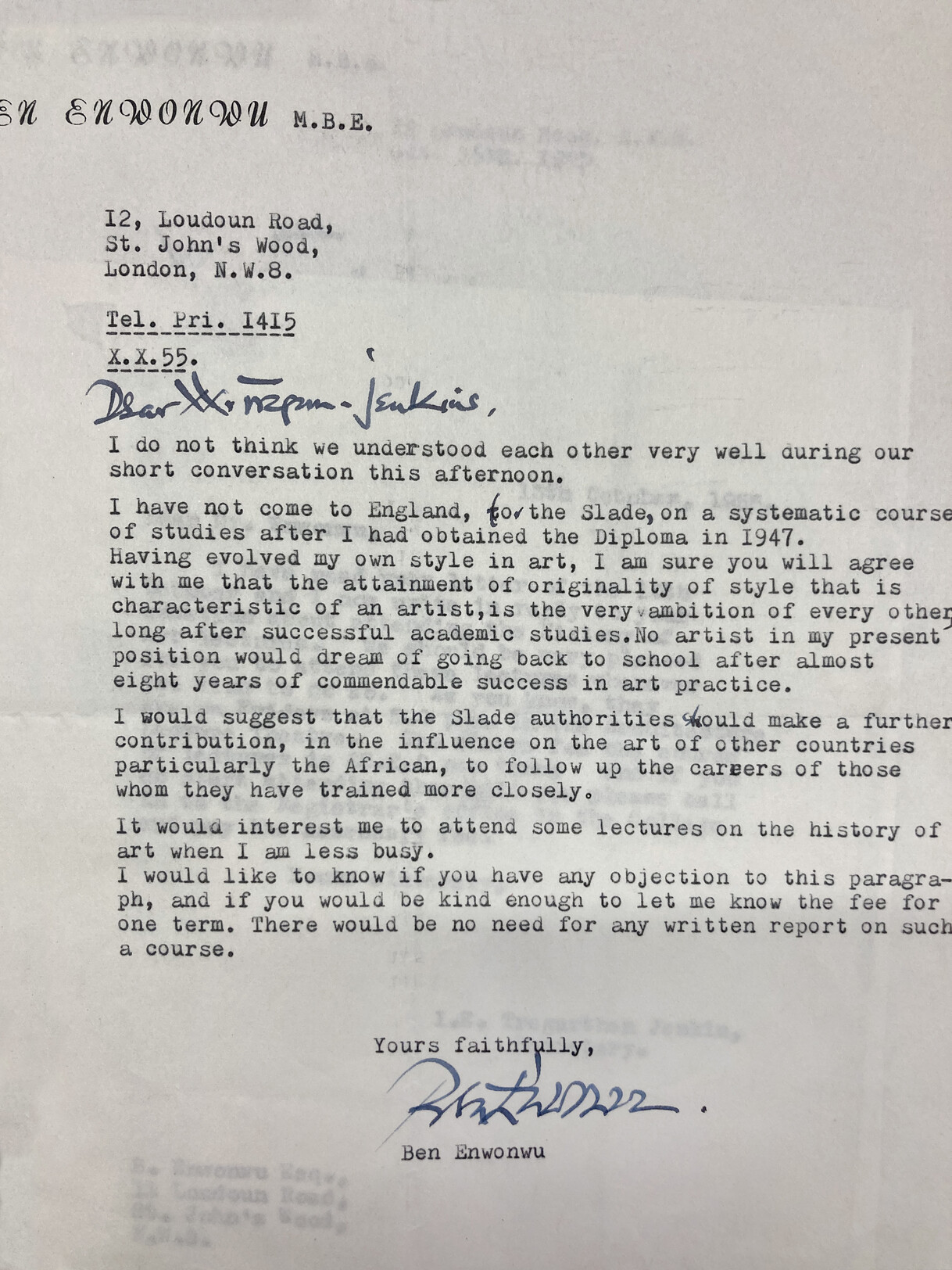

When his demands were not met, Enwonwu admonished the Slade authorities for not keeping up with his success and urged them to follow more closely the careers of those whom they have trained, especially those from African countries FIG. 2. Enwonwu took several months to respond to Tregarthen Jenkin’s answer to his letter, finally writing from his London address in October 1955. Earlier that year Enwonwu was awarded an MBE for his contributions to art and culture, and his new letterhead bears this insignia.

In 1956 Enwonwu was commissioned to create an official portrait of Elizabeth II FIG. 3. This originated with the artist himself, who contacted Alan Lennox-Boyd, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, with the intention of creating a sculpture to mark the queen’s visit to Nigeria in 1956. The queen sat for him a dozen times, including at Buckingham Palace, and the bronze sculpture was completed in 1957. It was then shipped to Lagos, to be displayed at the entrance to the Nigerian House of Representatives, in preparation for independence in 1960.8

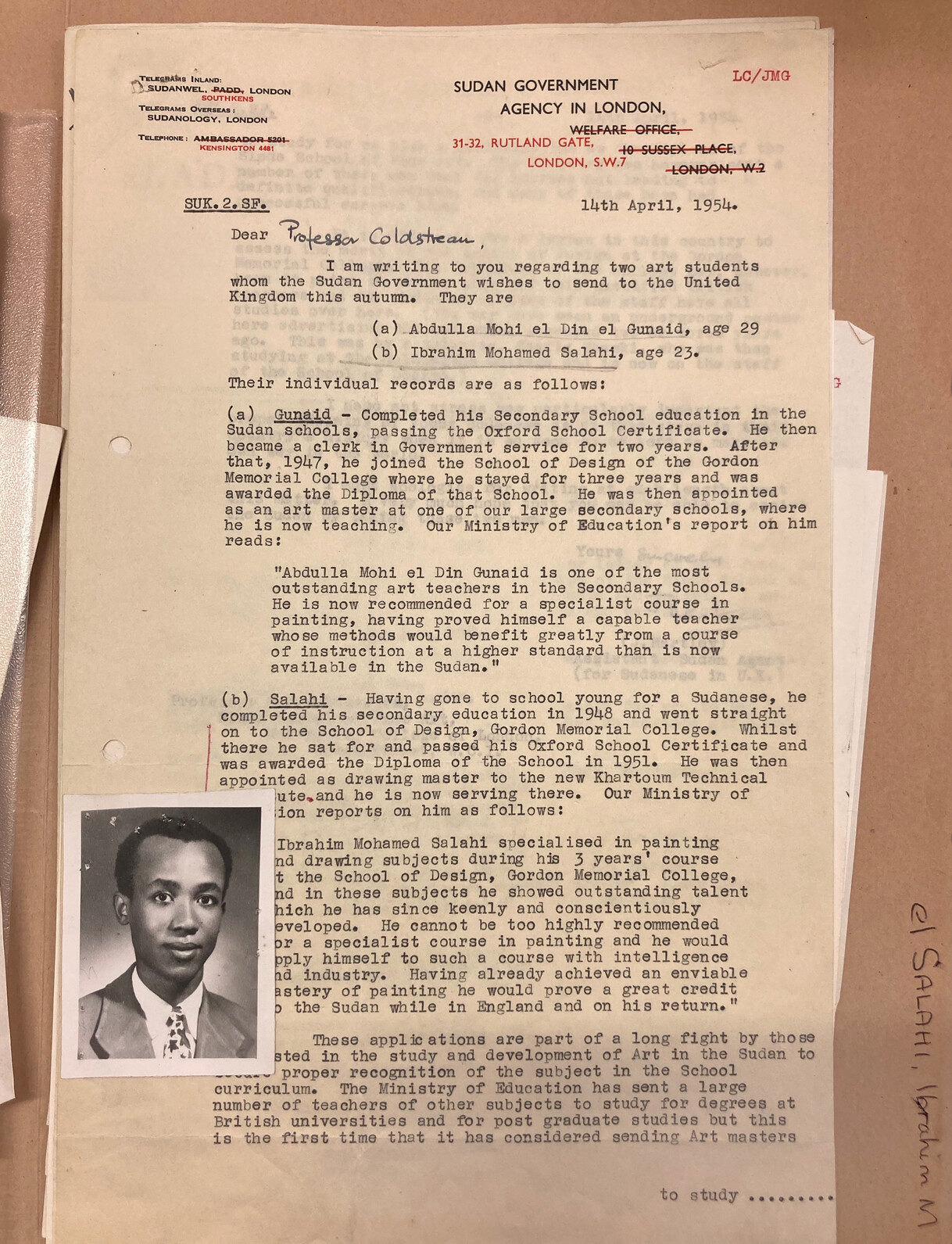

A year prior to Enwonwu’s request to attend a refresher course at the Slade, Ibrahim Mohamed El-Salahi (b.1930; known today as Ibrahim El-Salahi), along with Abdulla Mohi Din el Gunaid, won a scholarship courtesy of the Sudanese government to study at the school for a three-year course from 1954 to 1957 FIG. 4.

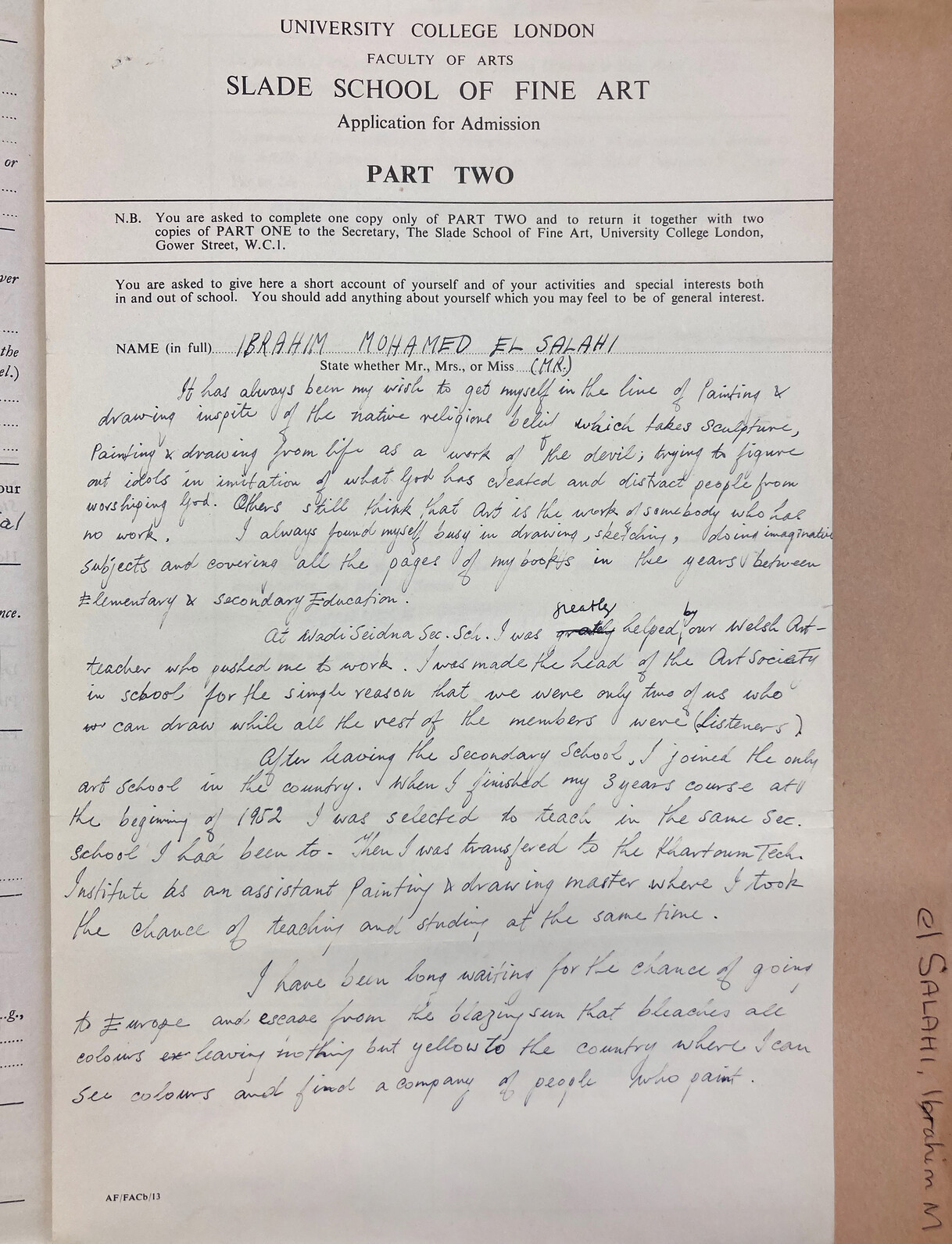

In his application to the Slade FIG. 5, El-Salahi expresses his desire to study in London: ‘It has always been my wish to get myself in the line of painting and drawing in spite of the native religious belief which takes sculpture, painting and drawing from life as a work of the devil, trying to figure out idols in imitation of what God has created and distract people from God’. He continues: ‘I have been long waiting for the chance of going to Europe and escape from the blazing sun that bleaches all colours leaving nothing but yellow to the country where I can see colours and find a company of people who paint’.

El-Salahi had been introduced to Western empirical approaches to visual art by British colonial artists at Sudan’s Gordon Memorial College, where he studied from 1949 to 1950. At the Slade, El-Salahi attended compulsory courses in anatomy and life drawing FIG. 6, supplemented by art-historical lectures by eminent art historians, such as E.H. Gombrich, whose book The Story of Art (1950) was set reading for students.9

As previously mentioned, the Slade curriculum had been based on a Beaux-Arts model, however this changed with the appointment of William Coldstream (1908–87) in 1949.10 Coldstream reorientated the school’s focus towards methods of enquiry, moving away from Antique models and idealised aesthetics. Based on his experience with the Euston Road School, which sought to create works that were accessible to a larger public through observational realism and engagement with social issues, Coldstream established an environment where representation and form were aligned with research and society.11 In the wake of the Second World War, these reforms pivoted students away from the history of continental European art as the model for artmaking. They were encouraged to articulate their own vision of the world.

After graduating from the Slade in 1957, El-Salahi returned to Sudan to teach at the College of Fine and Applied Arts. He became a key member of the Khartoum School, a group of artists formed in 1961 that sought to develop a new visual vocabulary for the independent nation. Although some scholars argue that El-Salahi overthrew his academic training from the Slade, one could argue that Coldstream’s example had taught him that there was more than one way to be modern.12

El-Salahi’s They Always Appear FIG. 7 is part of a series of eight paintings that he began in 1961. Despite complaining about ‘the blazing sun’ in his application to the Slade, El-Salahi adopts Sudan’s sun-baked earth tones in this work. The painting combines mask-like figures, a well-known trope of artistic modernism, with the curved lines, spheres and crescents of Arabic calligraphy and Islamic art. Although El-Salahi’s work fulfilled the expectations of a nationalist art in Sudan, it is a mistake to understand it purely in these terms. El-Salahi’s work transcends national bounds, exemplifying a postcolonial aesthetic in dialogue with metropolitan developments, while also taking account of regional and national specificities.13

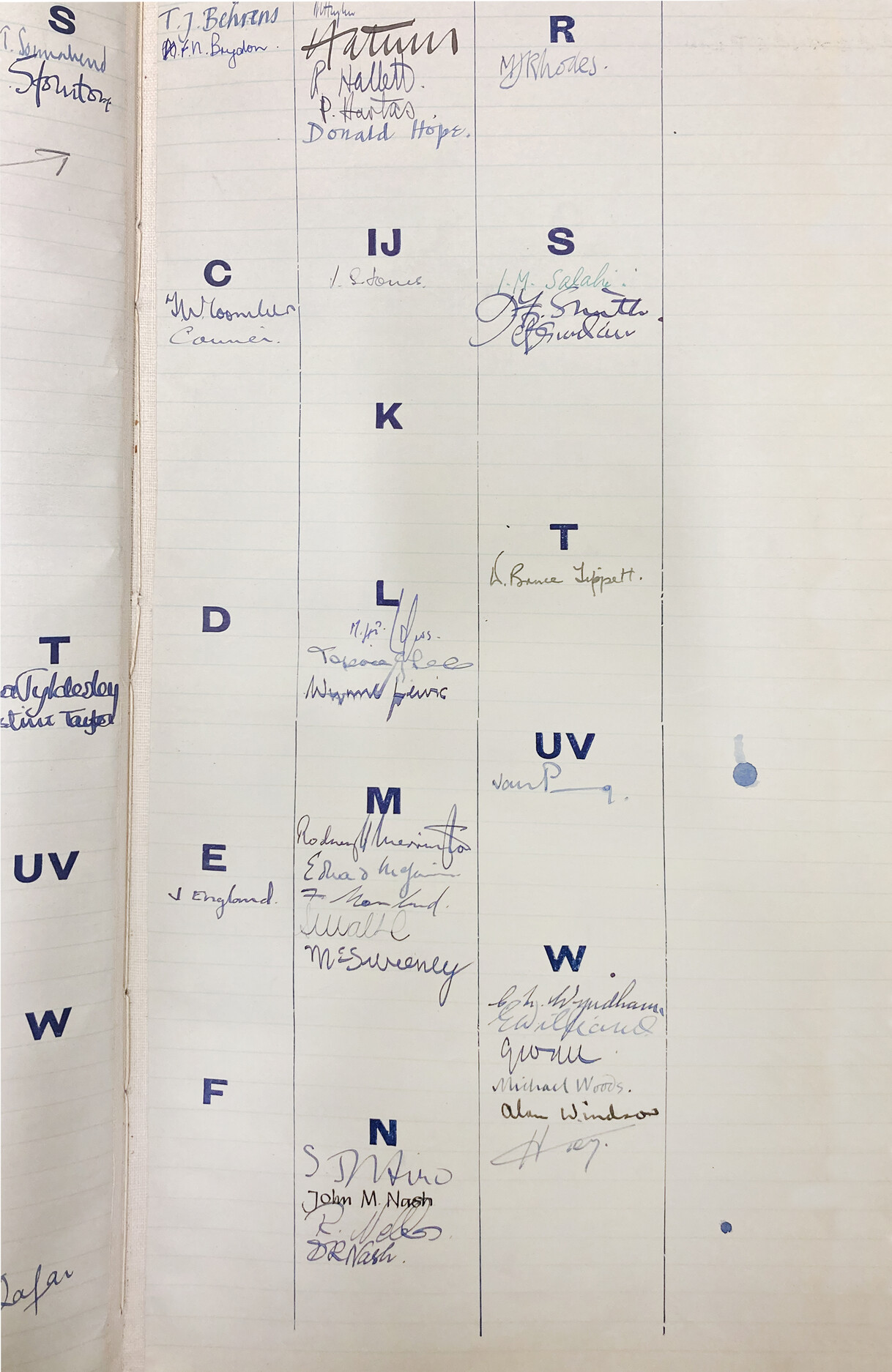

At the Slade, El-Salahi studied alongside the Tanzanian-born artist Sam Joseph Ntiro (1923–99), who attended the school from 1952 to 1955. This sign-in sheet FIG. 8 shows both artists entered the Slade building on 4th October 1954. Ntiro is the first signature under ‘N’ and El-Salahi is the first signature under ‘S’.

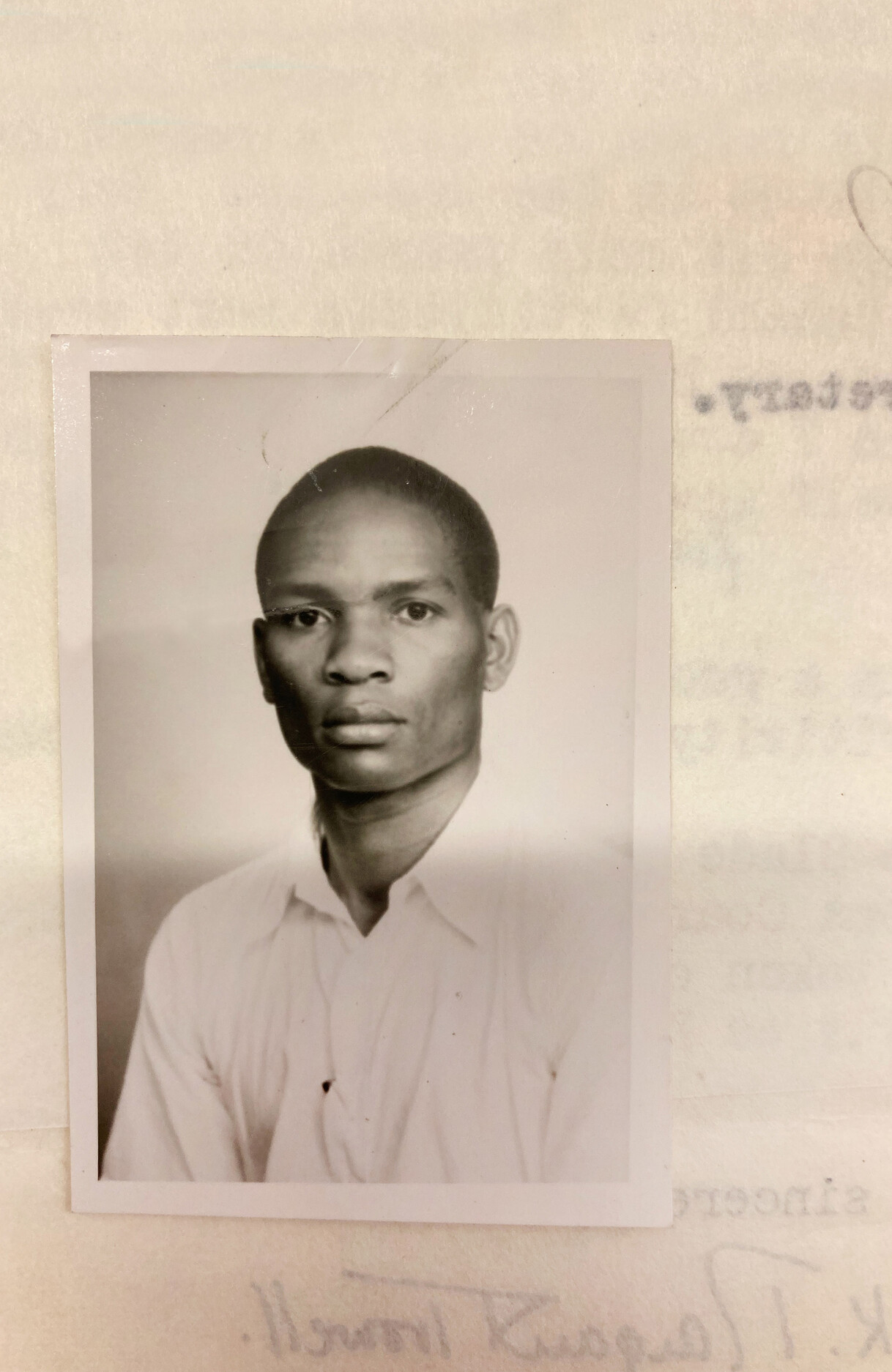

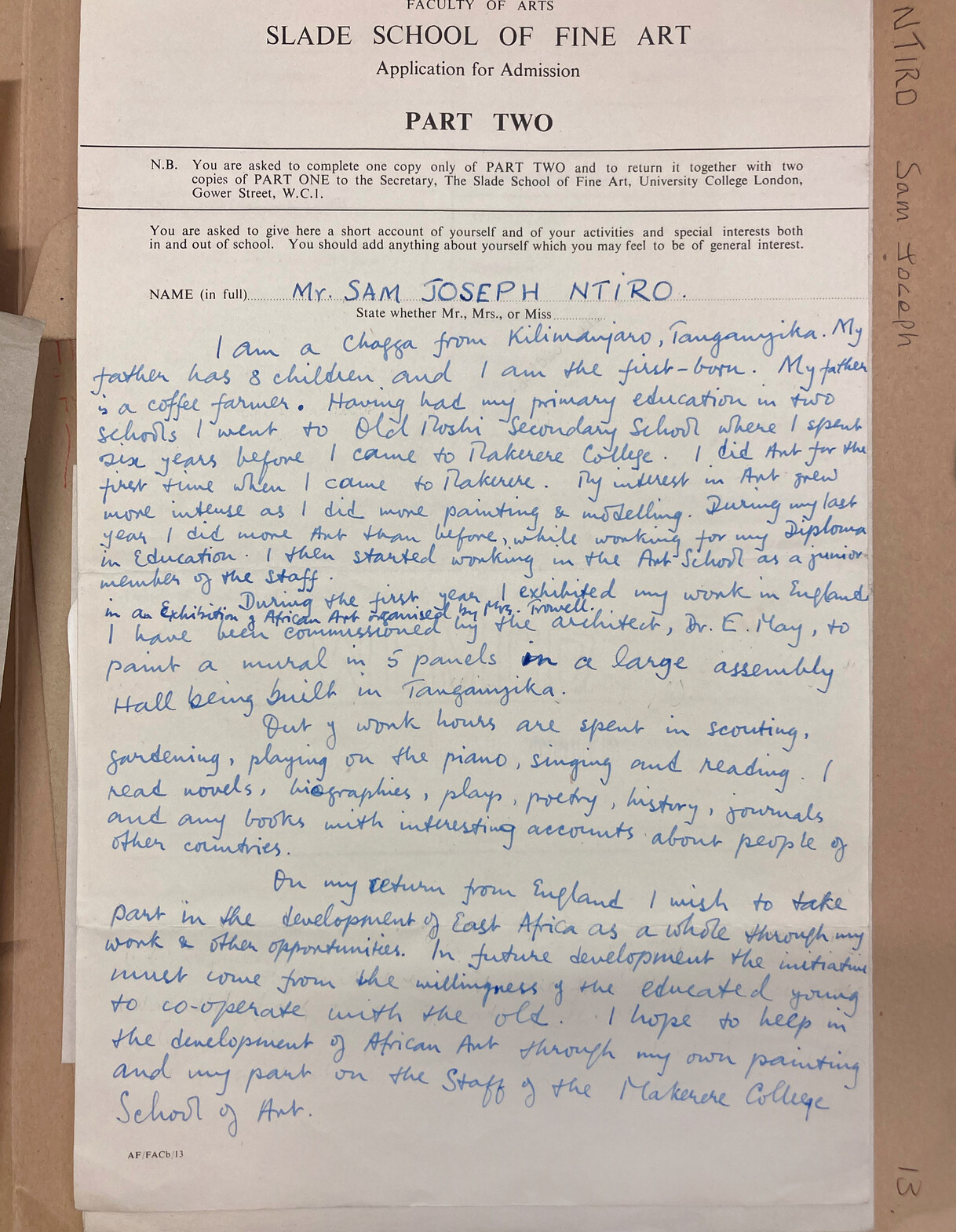

In his application to the Slade FIG. 9 FIG. 10, Ntiro states that he ‘did Art for the first time’ while studying at Makerere University College in Kampala between 1944 and 1947. Ntiro belonged to the Chagga people, who lived on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, and his father was a coffee farmer. Ntiro completed primary and secondary education in Moshi, a municipality on the lower slopes of Kilimanjaro, before leaving the country for tertiary education in Uganda. At Makerere, Ntiro was taught by Margaret Trowell (1904–85), a Slade alumna who had established formal art education in Uganda in 1937. Upon graduation in 1947, Ntiro was invited to join the school’s teaching faculty. With Trowell’s encouragement, he applied to the Slade in 1951 and enrolled in 1952.

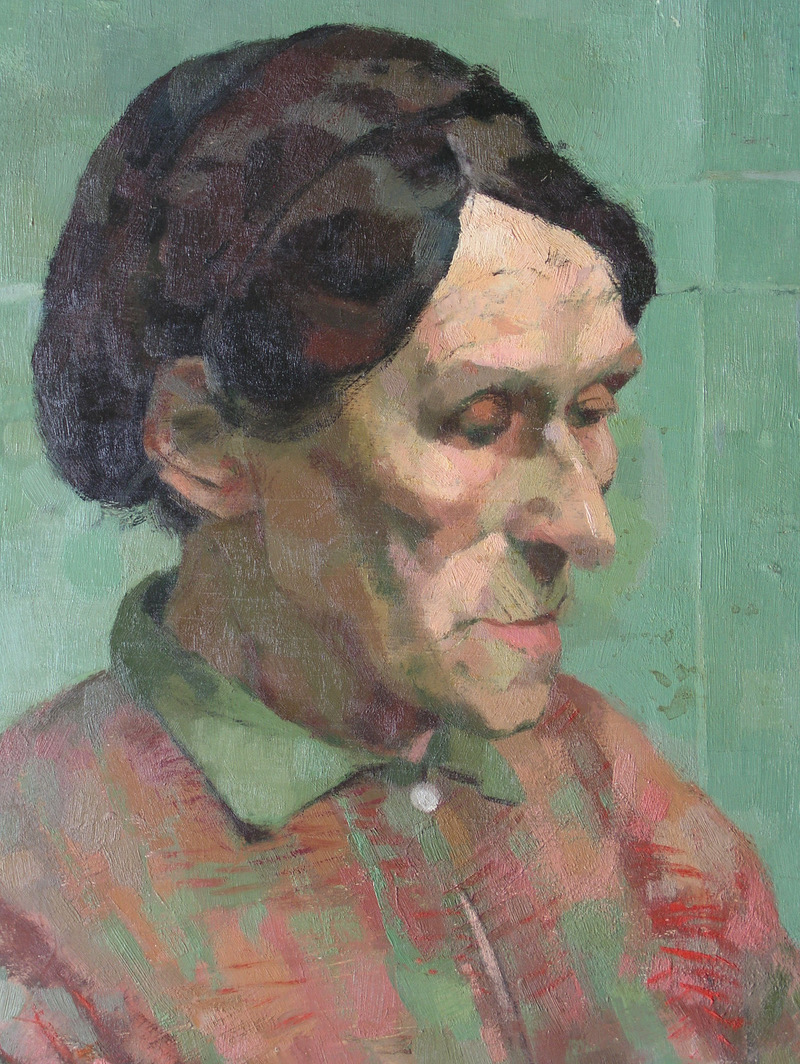

El-Salahi and Ntiro were classmates of the Portuguese-born artist Paula Rego (1935–2022). In 1954 they competed against each other in the Slade’s Summer Composition Competition. Rego’s painting Under Milk Wood FIG. 11 won joint first prize with works by Patricia Gerrard (1935–2000) and Margaret J. Rees. In 1954–55, Rego also shared the prize for a painting of a head with the Chinese artist Tseng Yu (b.1923). Like Rego, Gerrard FIG. 12 and Rees FIG. 13 depicted passages from Under Milk Wood by Dylan Thomas, which was first broadcast as a radio play in the same year as the competition. In addition to Under Milk Wood, students had the option of choosing from either the biblical scene of Jesus raising Jairus’s daughter or the myth of Apollo and Daphne from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. As a student of Trowell, Ntiro would have been familiar with the representation of biblical scenes, as his former teacher believed in spreading the gospel through visual arts.14 Ntiro often portrayed these Christian themes in an African setting. Only the winners of the Slade prize system were acquired by the UCL Art Museum, London, so it is only possible to speculate on the work submitted by other students.

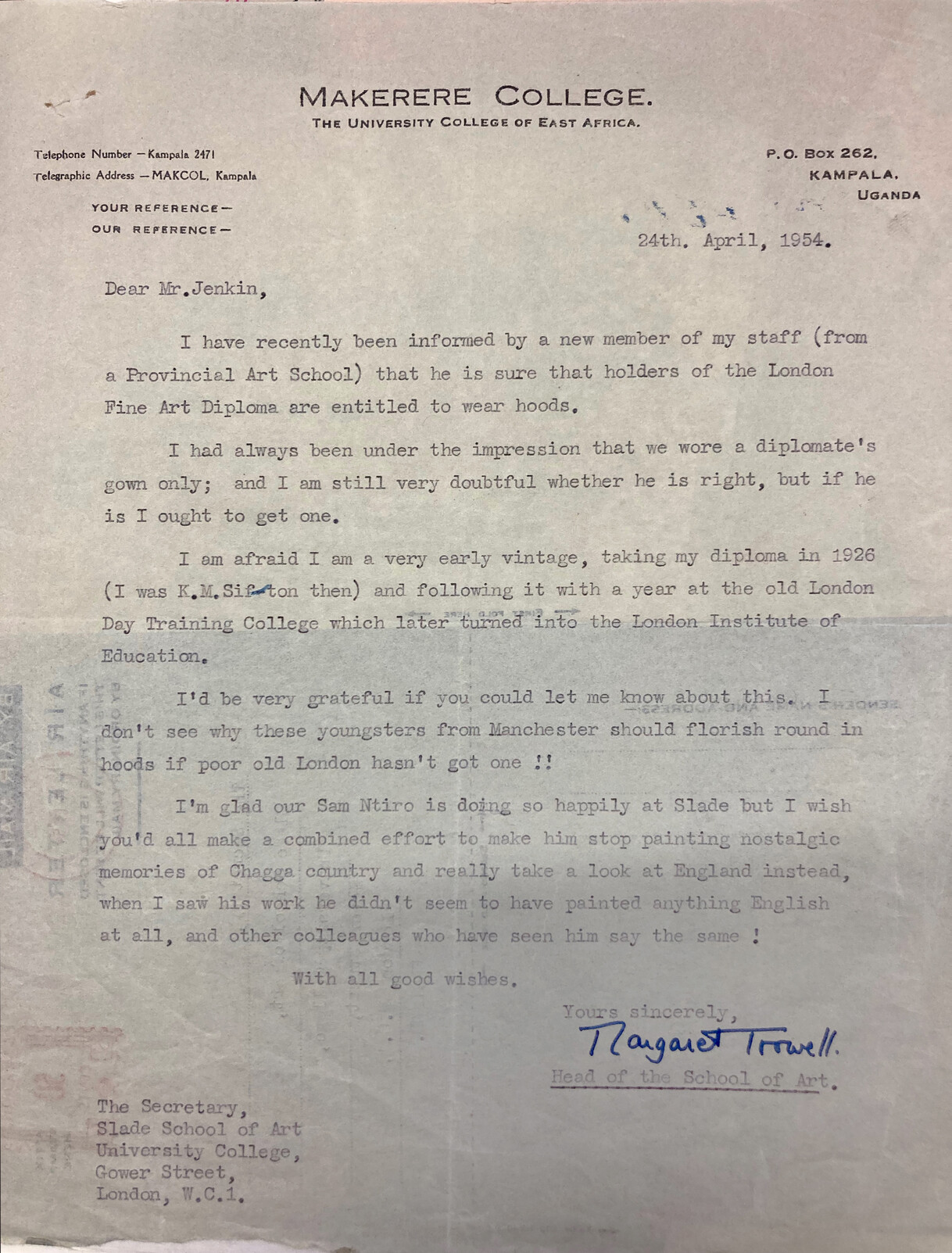

On 24th April 1954 Trowell wrote to Tregarthen Jenkin FIG. 14, commenting on Ntiro: ‘I’m glad our Sam Ntiro is doing so happily at Slade but I wish you’d make a combined effort to make him stop painting nostalgic memories of Chagga country and really take a look at England instead, when I saw his work he didn’t seem to have painted anything English at all, and other colleagues who have seen him say the same!’. Ntiro’s favoured subject matter was scenes of everyday life in Chagga country. Based on this choice, there was an assumption that the artist’s references were limited to this world. On the occasion of Ntiro’s debut show at Piccadilly Gallery, London, in 1955, the British press celebrated him for having been ‘untouched’ by his exposure to Western art education.15 The artist was praised for his ‘obstinate refusal to pick up painterly hints from Western civilisation. He could have easily done so and it would have destroyed him as an artist’.16 On the contrary, Ntiro only started to paint Chagga country in Kampala under the training of Trowell and subsequently in London at the Slade, collapsing the easy divide of ‘West’ and ‘non-West’ sought by critics. Moreover, in adopting painting to his own ends, Ntiro deliberately subverted the history and connotations of this long-standing ‘Western’ medium.

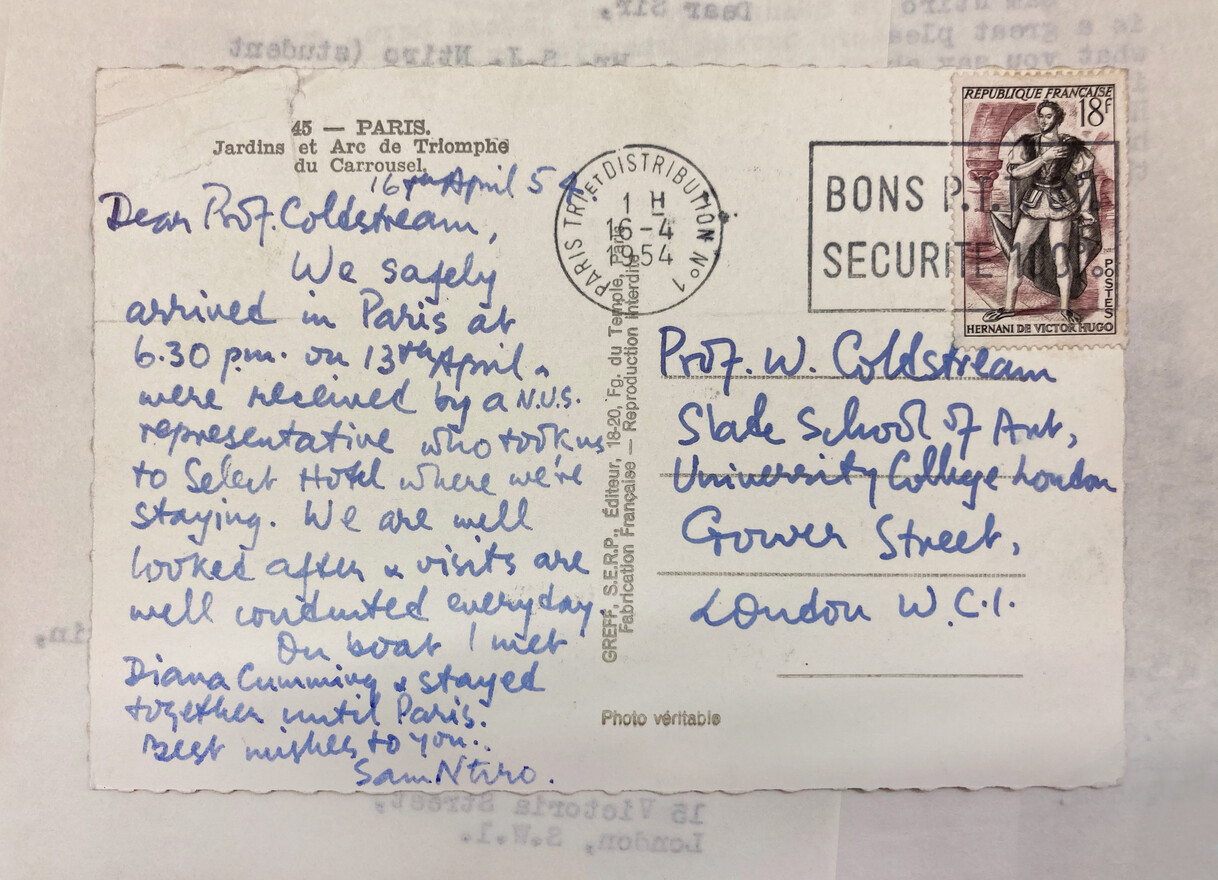

While at the Slade, Ntiro travelled to Italy and France, exposing himself to centuries of Western art history. In Paris, Ntiro sent a postcard to Coldstream FIG. 15, followed up by a letter on 26th April 1954, in which he stated: ‘On the whole I liked the pictures in the French Impressionist Gallery best, especially H. Rousseau, Renoir and Van Gogh’. Ntiro described being ‘completely captivated’ by two paintings: The martyrdom of St Sebastian by Piero del Pollaiuolo (after 1475; National Gallery, London) and Joseph the Carpenter by Georges de La Tour (1642; Musée du Louvre, Paris). Indeed, the illumination of the candle in the latter work brings to mind Ntiro’s later renderings of Chagga country by firelight.

Ntiro was commissioned to create three paintings for the 1962 opening of the new Commonwealth Institute building on Kensington High Street, London. The resultant works – Banana Harvest FIG. 16, Village Gathering FIG. 17 and Cattle Drinking FIG. 18 – create a subversive vision of the Commonwealth for British audiences, one premised on Tanzanian self-government. There is a sense that for colonial, and subsequently postcolonial artists, the Western construct of the nation state mattered up until its achievement, i.e. the attainment of an independent state free from foreign rule, and yet it endures as the interpretative frame of art history. Upon graduation in 1955, Ntiro returned to teach at Makerere University College, leading classes on perspective.17 Writing to Tregarthen Jenkin on 16th October 1958, Ntiro expressed his hopes for self-government. He also responded to an inquiry about the Capricorn Africa Society, stating: ‘You asked me about Capricorn Africa Society. It is regarded by Africans in East Africa as a means of pacifying Africans and keeping from attaining self-government’. The society was founded in Southern Rhodesia in 1948 by David Stirling, a Scottish officer in the British Army and the founder of the Special Air Service. Led by Europeans, the group believed that the countries of southern and eastern Africa could prosper if all races shared common loyalty to their countries, one based on belief in a shared future. Their proposals were rejected by white settler opposition and the rising tide of African nationalism to which they objected.18 After Tanzania gained independence in 1961, Ntiro returned to London to serve as the first East African High Commissioner to the Court of Saint James in London from 1961 to 1964.

Of note in the paintings made for the Commonwealth Institute is the attention to detail Ntiro paid to the flora and fauna of Chagga country. Calling to mind Ntiro’s reference to Rousseau in his 1954 letter to Coldstream, his plants are rendered with an intricate care for botany. He appears to use a variety of brushes and strokes to depict the leaves on the trees, varying from bulbous and round to loose and wispy. Contrary to the impression of Trowell and British critics, Ntiro adopted the techniques of Western painting to preserve his memories of Chagga country.19

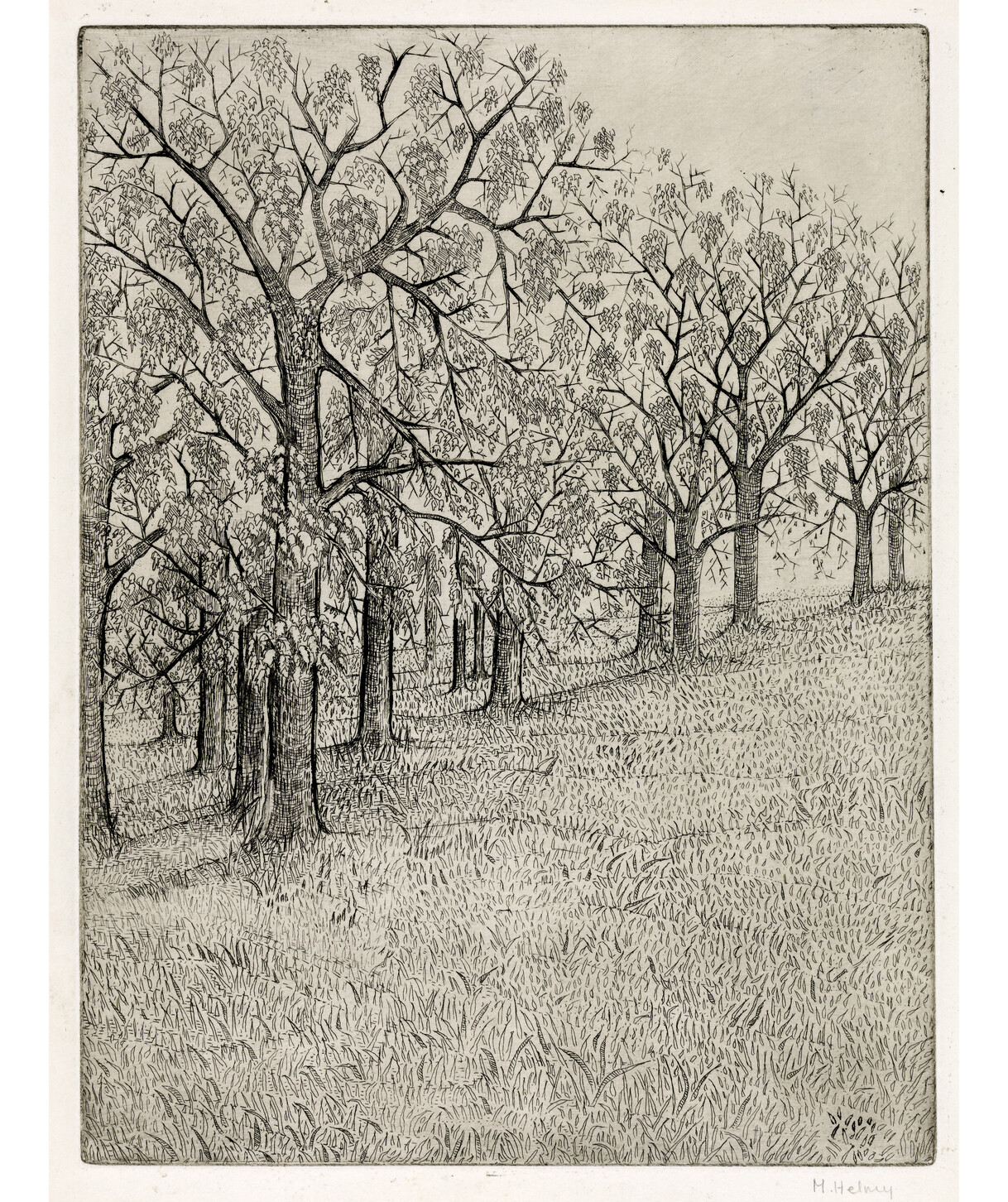

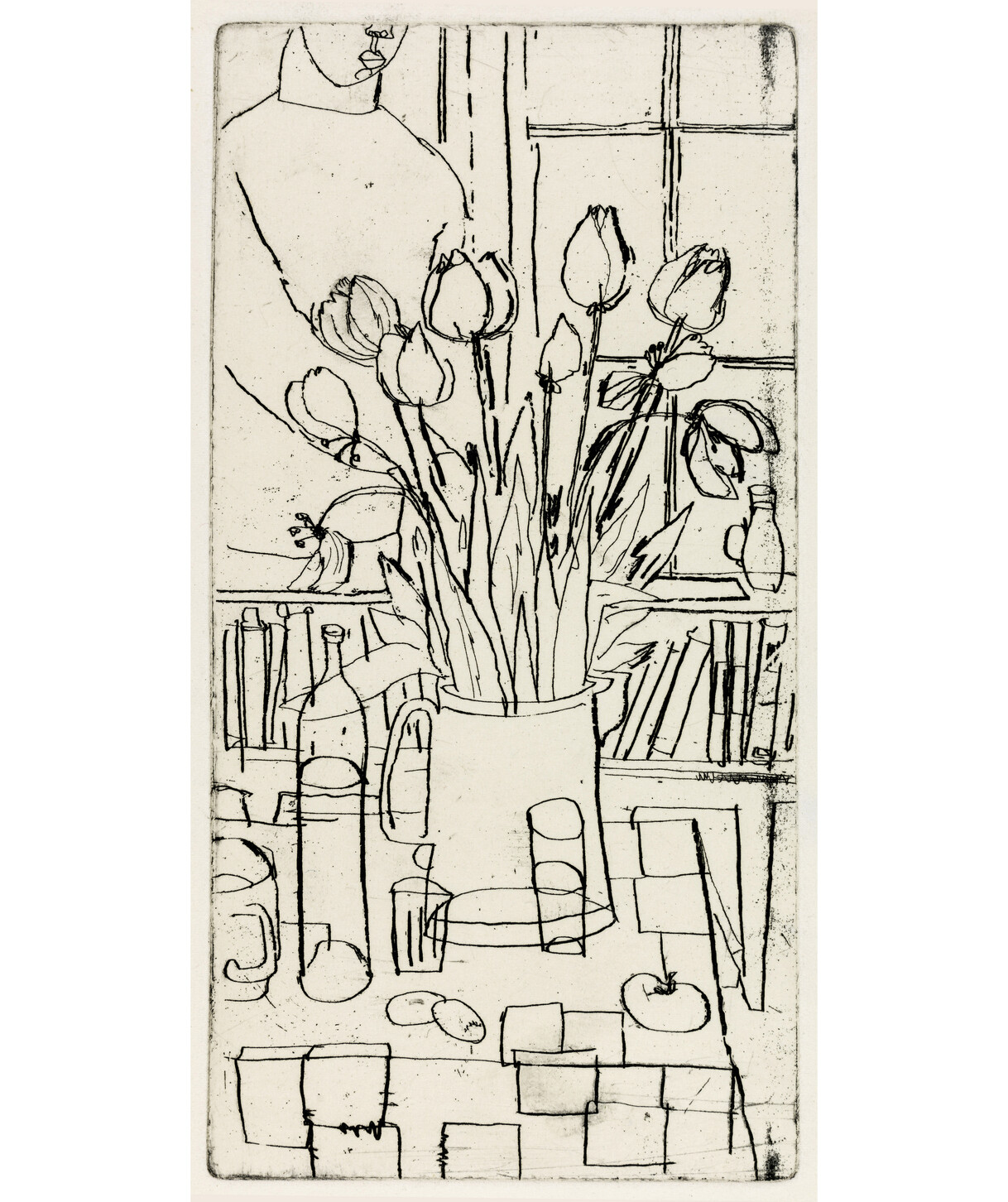

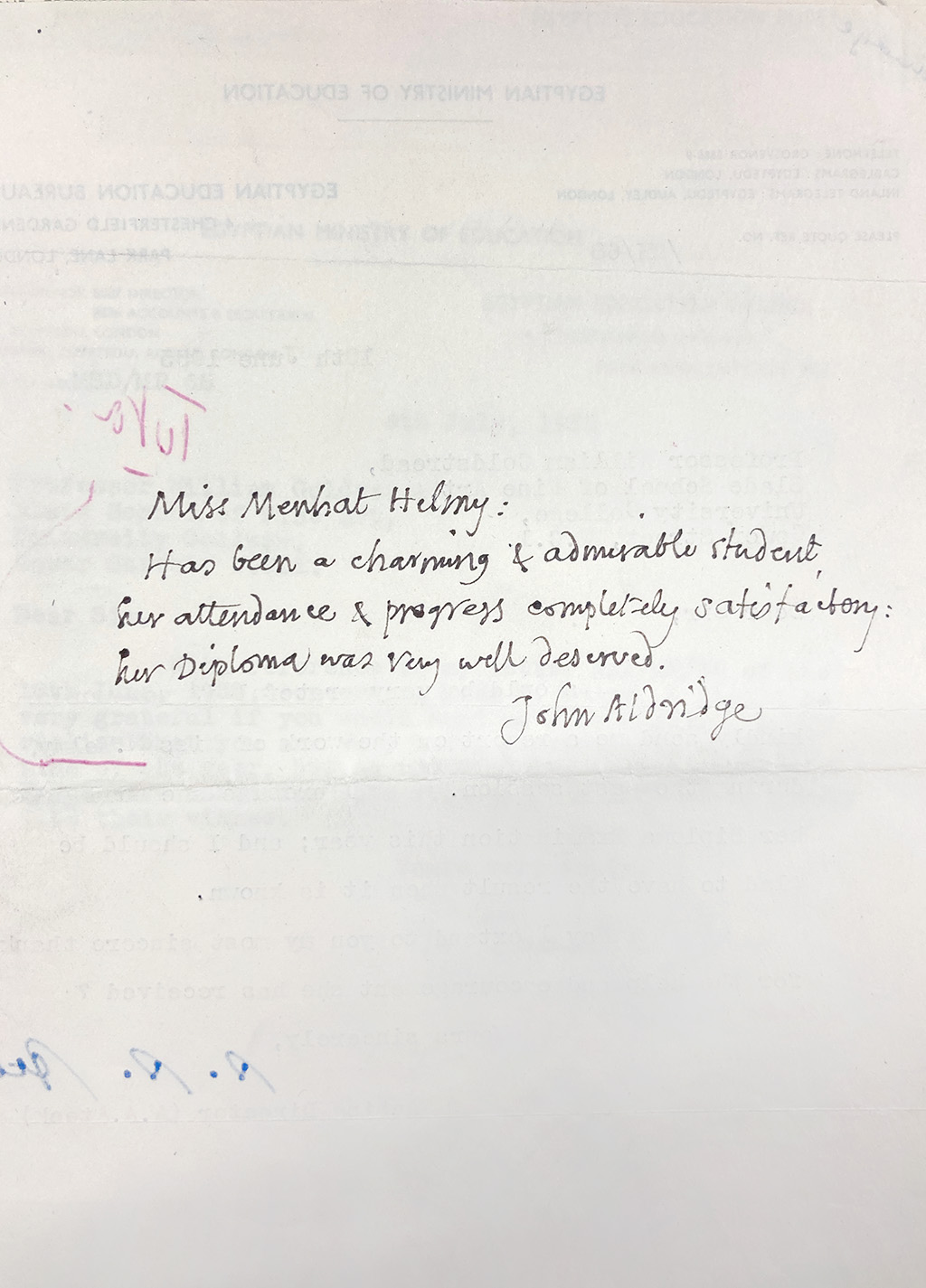

The Egyptian artist Menhat Helmy (1924–2005) studied at the Slade from 1952 to 1955. Her classmates included El-Salahi, Ntiro and Rego. Her work Landscape FIG. 19 was awarded the prize for etching and engraving in the 1954–55 session alongside a print by the British artist Michael Tyzack (1933–2007) FIG. 20. With Tyzack and Helmy’s similar treatment of plants, it is easy to imagine these works being completed in the same classroom.

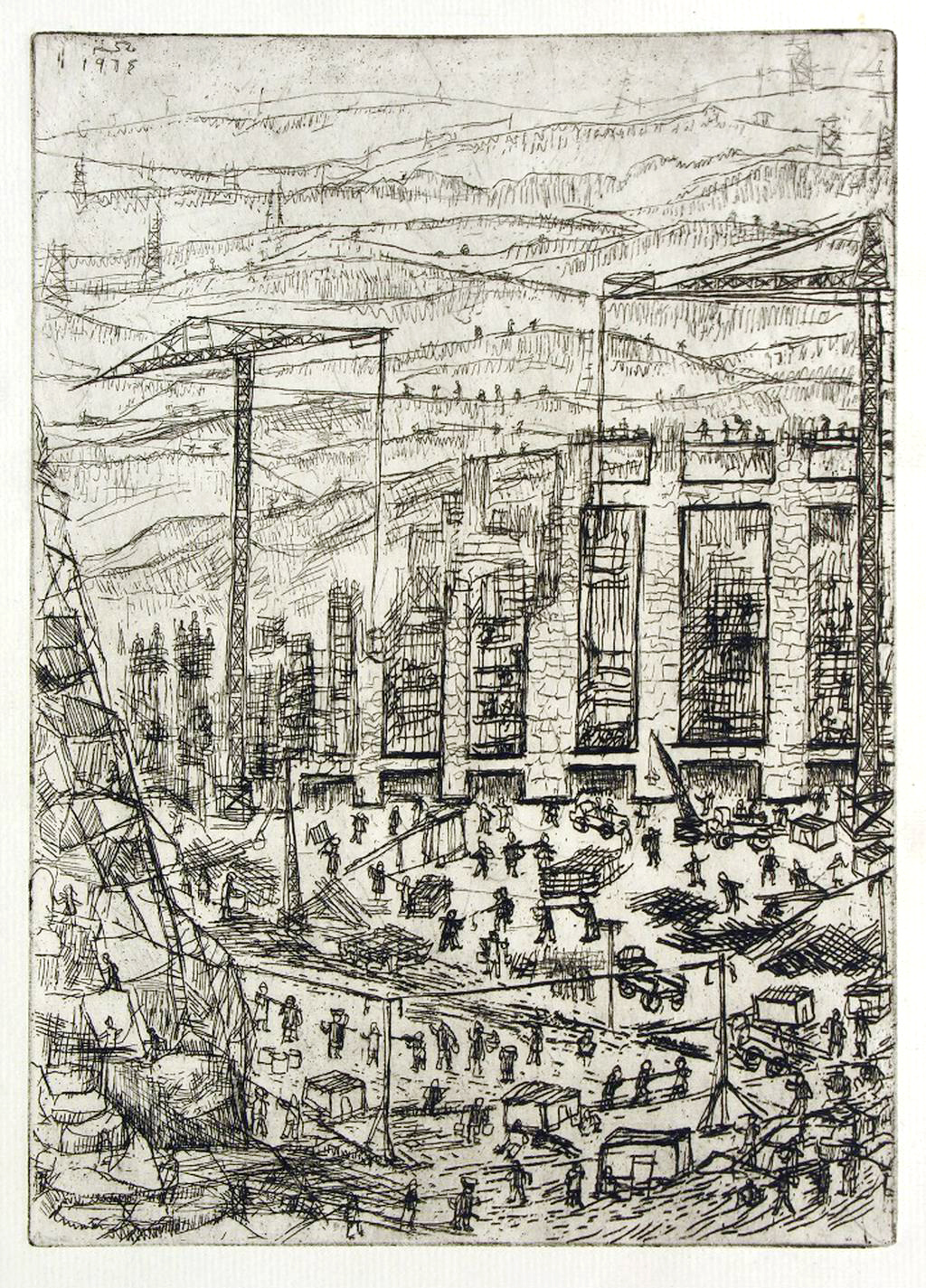

After receiving her diploma FIG. 21, Helmy returned to Egypt. Through her newly developed skills in etching honed at the Slade, she documented the changes in the country spurred by the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 and the ascent of the Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. One of Helmy’s etchings depicts the construction of the Aswan High Dam FIG. 22.

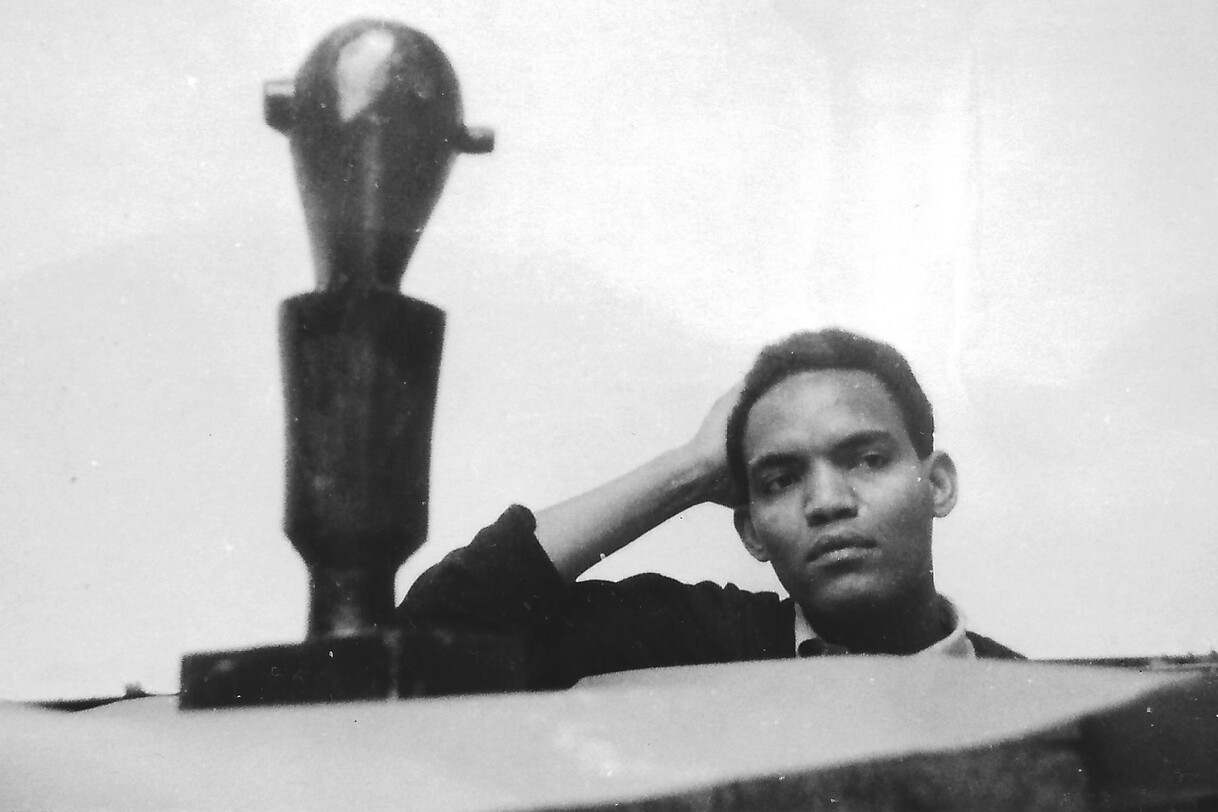

Supported by a grant from the Sudanese government, Amir Nour (b.1939) studied at the Slade for a Diploma in Fine Art between 1959 and 1962 FIG. 23. In his application, Nour states that he wished to see the wider world, ‘a world of Michael Angelo [sic], Rodin and Henry Moore’. One of the referees for his application was El-Salahi.

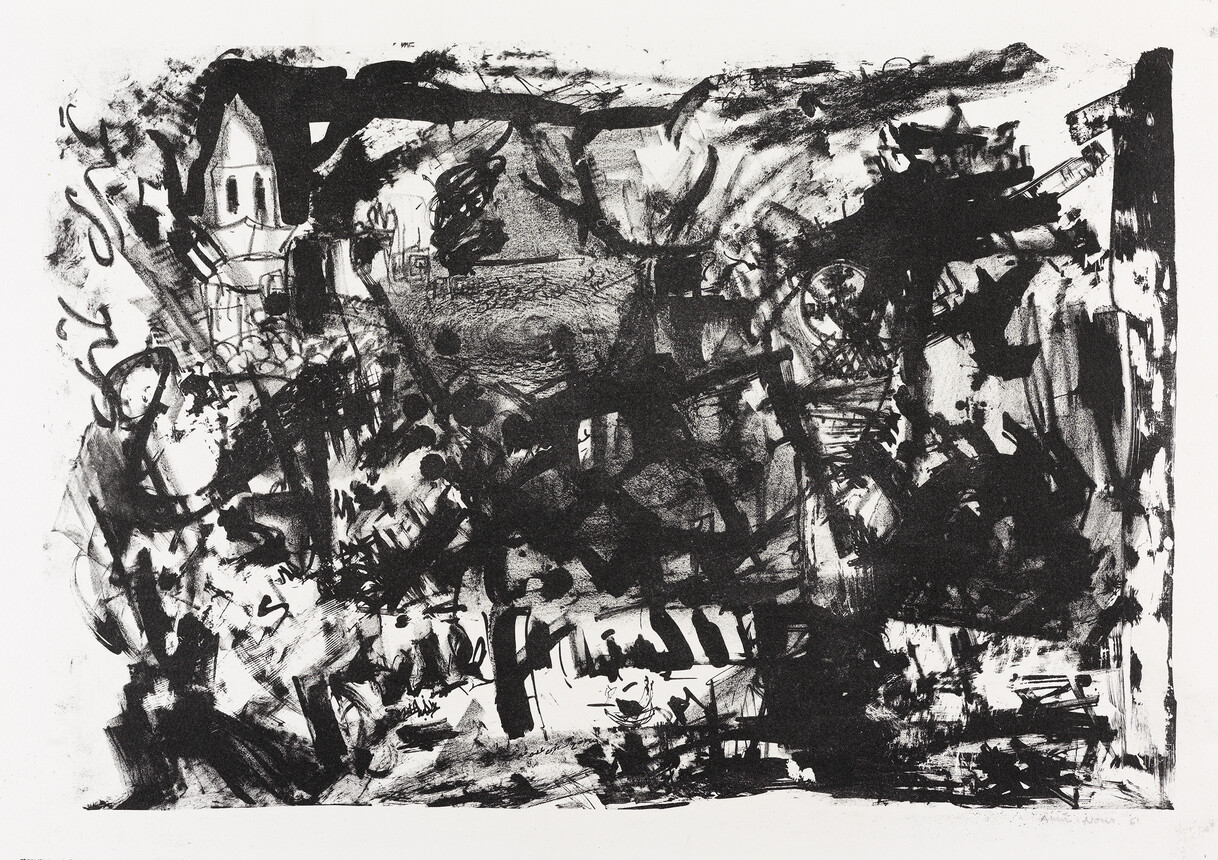

Although Nour specialised in sculpture under the Slade tutor Reg Butler (1913–81), he also excelled in printmaking FIG. 24, winning the prize for lithography in the session of 1961–62. He petitioned to remain at the Slade for a further year after taking his diploma, but his request was rejected by the Sudanese government.

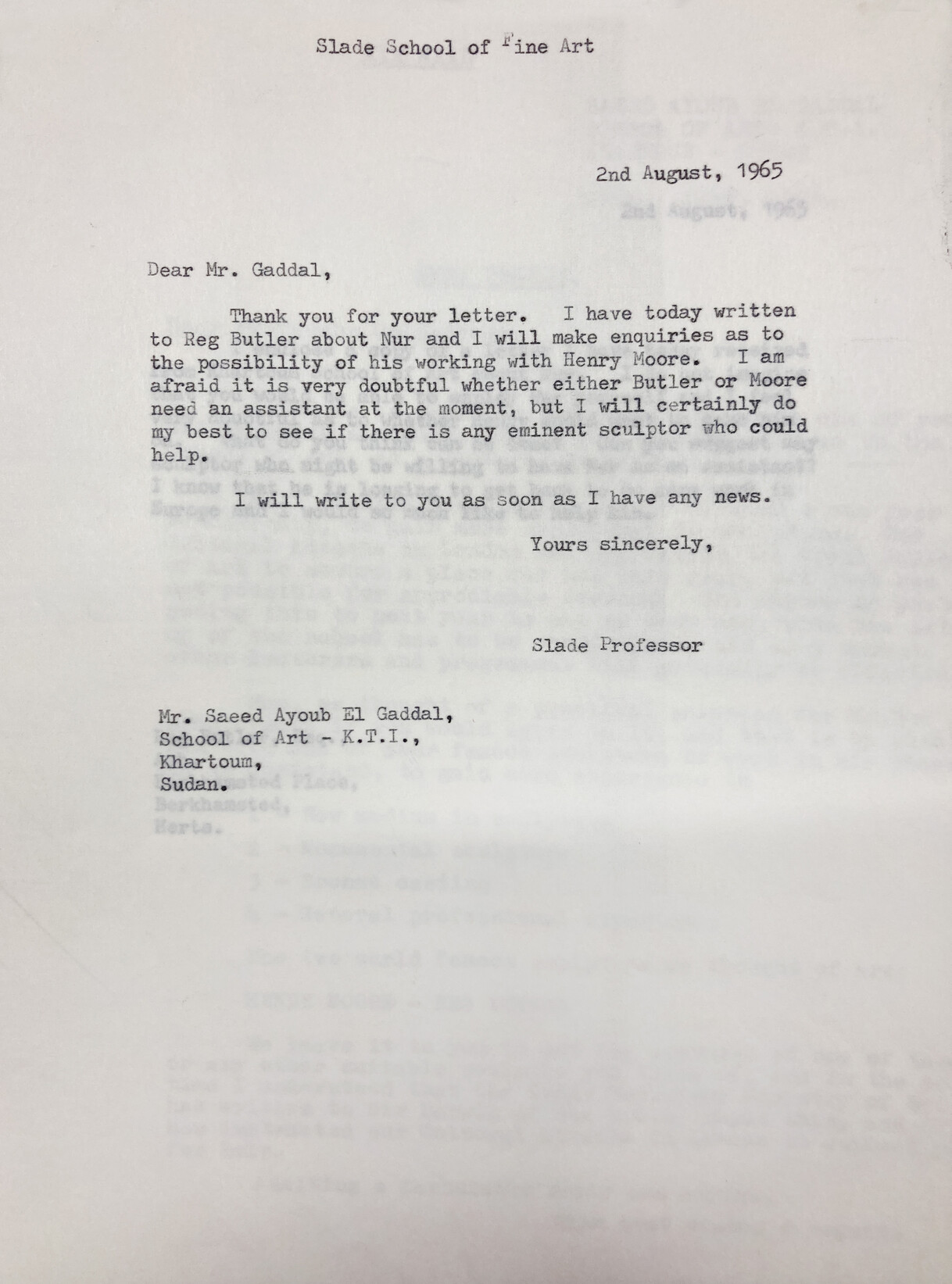

After graduation, Nour returned to Khartoum to teach for three years before he was awarded a one-year scholarship by the Sudanese government for postgraduate work. Nour wanted to study at the Slade, but the school did not yet offer a postgraduate course in sculpture and bronze casting. An alternative was proposed for Nour to seek out professional experience with either Butler or Moore FIG. 25. Instead, he completed a postgraduate course in sculpture at the Royal College of Art from 1965 to 1966.

In 1967 Nour was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship to study at Yale University where he completed a two-year BFA course before moving onto the one-year MFA degree. At Yale, Nour continued to take classes in Western art theories and philosophies while expanding his studies in African and Islamic art.20 African and Islamic art had been absent from the curricula at the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Sudan as well as at the Slade. As Nour recalled:

The first time I heard any formal lectures on African art, particularly Yoruba art, was at Yale University in 1967. To learn about African art in a context other than ‘primitive art’ had a significant impact on me […] It was inspirational to hear Professor Robert F. Thompson lecturing on Yoruba art.21

This telling account of a Sudanese artist exposed to the study of African art only in the United States speaks to the complexities of lives lived and subsequently reduced by the categories of art history, which supposes innate knowledge on behalf of the artists. Nour was also exposed to Minimalism and its debates as part of a larger discussion emerging at the time around the work of such artists as Carl Andre (b.1935), Dan Flavin (1933–96), Donald Judd (1928–94), Sol LeWitt (1928–2007) and Robert Morris (1931–2018).22

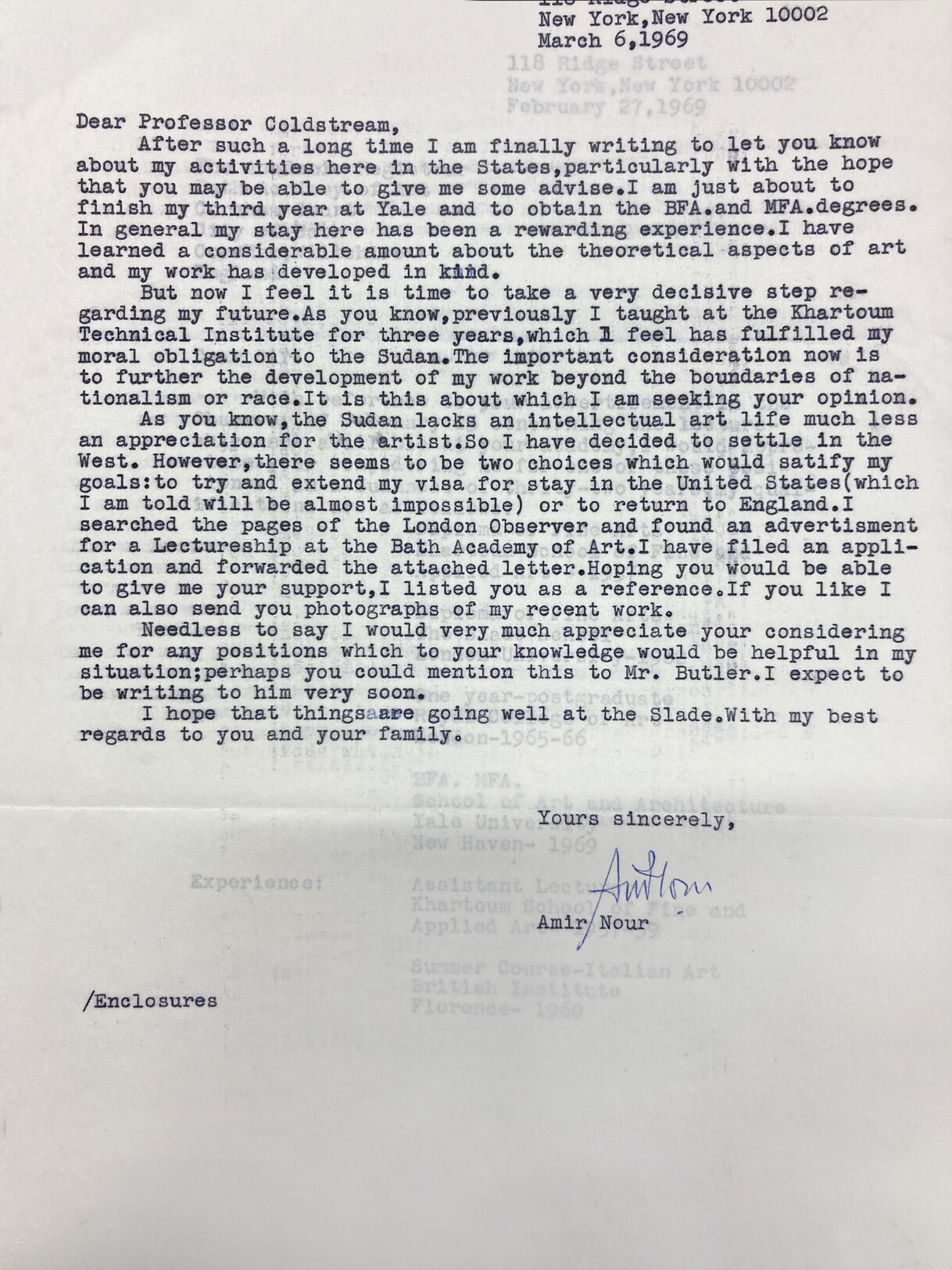

During his third year at Yale, Nour wrote to Coldstream on 6th March 1969 FIG. 26, expressing a sense of frustration with identity-based understandings of his work. He stated: ‘the important consideration now is to further the development of my work beyond the boundaries of nationalism or race’. He described his plans to stay in the West, declaring that ‘Sudan lacks an intellectual art life’. Over the course of the following years, Nour would request several references from Coldstream as he applied for teaching posts at various institutions in the United Kingdom and the United States.

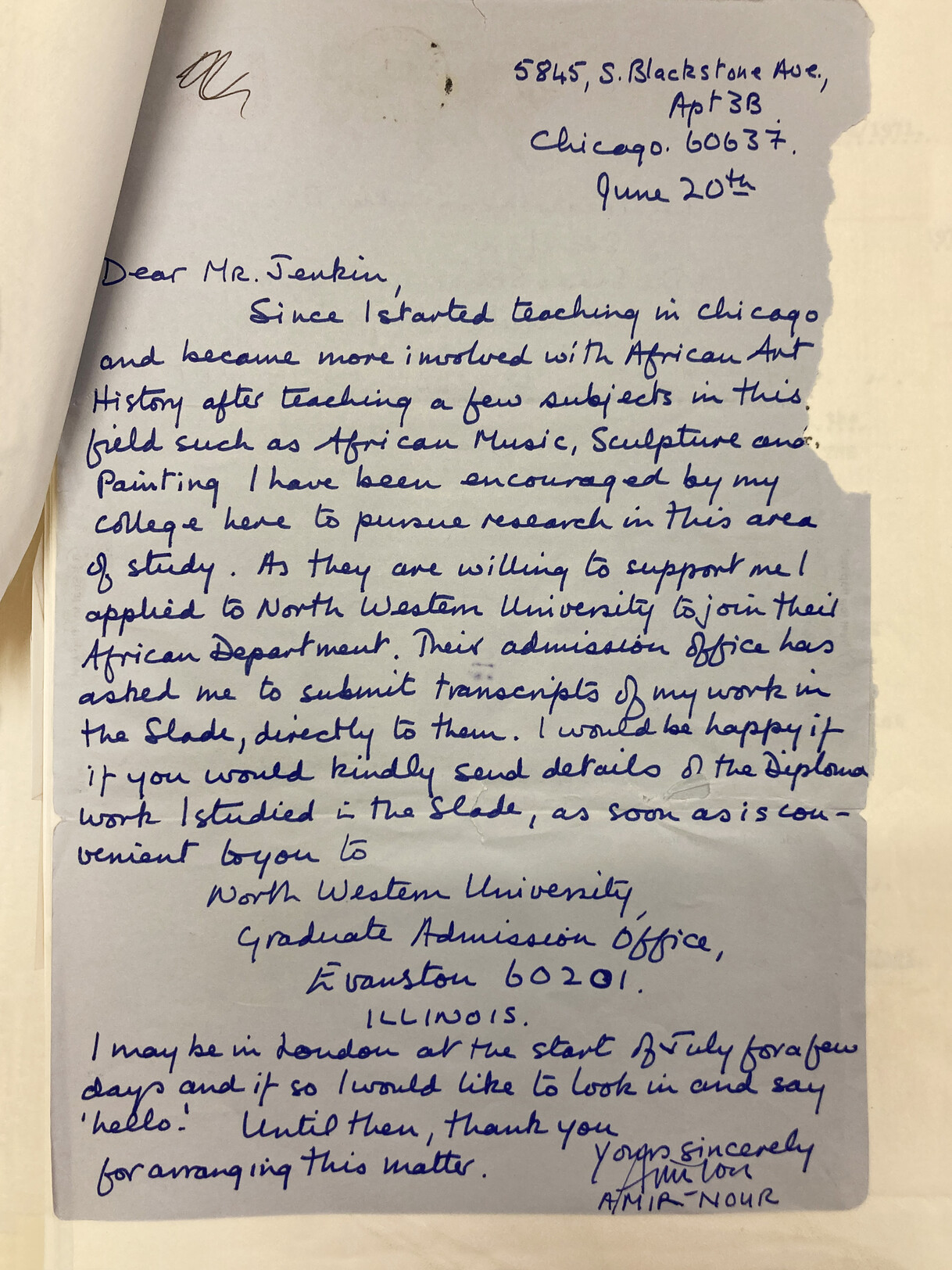

Nour eventually found success teaching ‘African Art History’ at the City Colleges of Chicago FIG. 27. He was encouraged to pursue this area of research by the College of Fine and Applied Arts and applied to join the African Department at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. In Chicago, Nour benefited from artistic exchange with the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA), a collective made up of artists who had found a new resonance in their African ancestral heritage following the global decolonisation movement, as well as with other sculptors, such as Richard Hunt (b.1935) and Melvin Edwards (b.1937).23

In the 1969 letter addressed to Coldstream, Nour expressed a desire for his work to escape the confines of nationalism and race. An artist who straddled multiple worlds, Nour appears to have been met with a limited capacity for understanding the transnationalism of his work at the time – a limitation that arguably still affects the contextualisation of his work. In 1974 Nour was interviewed by Africa Report and photographed alongside his stainless-steel sculpture Grazing at Shendi FIG. 28, which comprises 202 semicircles of varying sizes. The work is based on the artist’s childhood memories of watching sheep graze on the hillside near his hometown of Shendi, an ancient city on the bank of the Nile River. In the interview, the reporter immediately attempts to situate Nour’s work in an African context to which the artist responds: ‘That’s a difficult question; I really can’t answer that’. Conversely, when Grazing at Shendi was first exhibited the critical reaction deemed it ‘too Western’ for an artist of African descent.24

Nour lamented being labelled as ‘Western’, noting that Western artists who borrowed from African art were never labelled as ‘African’.25 In reality, Grazing at Shendi is a work that transcends these cultural distinctions: it is based on the domes and arches, cattle horns, calabashes and sand hills of Nour’s homeland and combined with the visual vocabulary and materials of Minimalism. To adopt the headline from Africa Report, the case of Nour demonstrates the entangled ‘place of the African artist’ and the ways in which these labels derived from national and continental frameworks obfuscate more than they reveal about artmaking and identity formation – both then and now.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, London, for funding this research.