Between species: animal-human collaboration in contemporary art

by Chad Elias • November 2019

In his description of ‘the struggle for existence’ – the competition for scarce resources that forms the basis of the evolutionary process of natural selection – Charles Darwin noted ‘how plants and animals, most remote in the scale of nature, are bound together by a web of complex relations’.1 More recently, the philosopher Timothy Morton has put forward the concept of ‘mesh’ to describe an expanded ecological system in which ‘all living and non-living things’ are understood as interconnected and interdependent.2 Such a model of relations suggests it no longer makes sense to draw any hard distinctions between biological, mineral and vegetal actors.

For his contribution for dOCUMENTA 13 (2012), Pierre Huyghe constructed an elaborate biotope in the compost facility of Karlsaue Park, Kassel.3 The protagonists of A Way in Untilled included bees whose hive replaced the head of a replica Max Weber sculpture FIG. 1; an albino dog with one of its forelegs dyed pink; piles of disused concrete slabs FIG. 2; and an uprooted oak tree. In this assemblage, the human-centred protocols of the contemporary art exhibition give way to fuzzy assemblages of various ‘existents’.4 Moreover, the boundaries between what might be perceived as ‘artistic’ and ‘non-artistic’ are difficult to distinguish. On the one hand, works of art (the statue that supports the beehive; Huyghe’s installation as a whole) have been removed from their cultural container and brought into the ‘wild’, or the already existing ecosystem of the composting facility. On the other, biological and meteorological actors (weather systems, local flowering plants pollinated by the bees) have been aligned within the ‘cultural’ or institutional framework of the exhibition.5 As the boundary between humans and nonhumans is destabilised, so too is the distinction between the anthropic gaze and its subject, or the museum and the work of art.

In Huyghe’s recent work with living organisms, as well as in projects by the British artists Olly and Suzi (Olly Williams and Suzi Winstanley), who make art in the wild with the involvement of endangered species, non-human animals are enlisted as collaborators in the joint production of works of art across species boundaries. Yet what distinguishes both bodies of work is that they pose a further challenge to the institutional frameworks within which this division has been naturalised. These frameworks cannot be reduced to a discussion of specific art institutions, nor to the material sites of the museum or white-cube gallery. Rather, they should also be seen to include the social networks and discourses that make up the contemporary art world and the discipline of art history.6 If the museum is a structure that traditionally serves to separate nature and culture, in Untilled Huyghe turns the exhibition into a stochastic platform in which human action or intention is only one component, and in which there is no predictable pattern of responses or set of relations between organisms. In both bodies of work the relation between humans and animals is staked on distinctions that are as much institutional and cultural as they are biological.

Animal studies and art history

Situated at the juncture of evolutionary biology, ethology, literary theory and philosophy, the field of animal studies has sought to re-evaluate the human-animal relation from a post-humanist perspective.7 This methodology has entailed not only developing a more nuanced picture of animal behaviour and cognition, but also interrogating the humanist image of the knowing subject who, in contrast to animals, has a special claim over language and reflexive consciousness.

For such writers as Erica Fudge, Kari Weil and Cary Wolfe, the question is not so much what we think of animals but how animals and our interactions with them have historically shaped our world.8 Accordingly, they have questioned a model of cultural production in which animals have been conceived as ‘mere blank pages onto which humans wrote meaning’.9 One of the key questions of the discipline, then, also taken up by this essay, is how to recognise the singularity and alterity of animals while also acknowledging that other species are deeply intertwined with human culture and society. Might contemporary art that engages with animals allow the differences and connections between species to be understood outside of an entrenched division between culture and nature or between the art institution and what it contains?

In art history, the relatively recent turn towards questions of animal agency not only entails a reconsideration of what counts as a person in the legal and ethical sense, but also an extension of the conceptual boundaries or parameters that have come to define the label of artist. One recent example of this redefinition of the artist is the dispute over a selfie taken by Naruto, a macaque monkey in Indonesia, first published in 2011 FIG. 3. The camera’s owner, David J. Slater, was embroiled in a novel and protracted lawsuit over whether the monkey owned the rights to the widely circulated image, and in December 2014, the United States Copyright Office ruled that works created by a non-human are not copyrightable.10 Ron Broglio notes that in the long cultural and philosophical tradition to which contemporary art is heir, animals are said not to ‘practice the self-reflexive thought that provides humans with depth of being’.11 He argues, rather, that animals might be engaged precisely for their ability to live in a state of immediacy that is denied to humans, who remain trapped in the prison-house of language. Rather than discussing art that aims to assimilate ‘the animal’ and in doing so, to erase its difference or unintelligibility, Broglio foregrounds the work of artists who point to an animal phenomenology that remains, on some level, discontinuous with human modes of being in the world. In his essay ‘Sloughing the human’, Steve Baker similarly highlights a form of creative alliance that aims to ‘give full recognition to the part played by the animal’.12 Baker concedes that ‘it may not yet be entirely clear what is exchanged between the human and the animal’ in certain instances, but ‘the politics and poetics of that exchange call urgently for further exploration’.13

This essay takes up Baker’s call for further analysis of human-animal collaborations and analyses two bodies of work that occupy the no-man’s-land between species boundaries. This indeterminate space may not allow for mutual understanding, but it does offer a ‘contact zone’ wherein interspecies relations can be thought about differently. Moreover, in these works, this zone of indistinction not only concerns the boundaries between humans and non-human animals but also the cultural discourses and institutions through which speciesism is naturalised.

Olly and Suzi

Olly and Suzi have an unusual working method. They begin with figurative paintings of animals in traditional forms of art, such as oil painting, charcoal and watercolour. Then, wherever possible, they invite the depicted animals to engage with the paintings and mark them further themselves. These autographic inscriptions may take the form of footprints or other bodily traces that are registered on the surface of the paper.

The artists use materials designed to encourage animal interaction and response. In saline ecosystems, the artists use paper that responds well to sustained immersion in salt water, along with non-toxic paints, charcoal or crayon. In other aquatic works they have been known to employ lichen, kelp and underwater rocks and plants for pigment. Off the coast of South Africa, Olly and Suzi used water-based pigments, graphite and oil sticks to paint and draw underwater in close proximity to great white sharks. The artists then mounted the pictures (executed on paper) on large buoyant foam board with the underside covered in dark tones. This created a silhouette that encouraged the sharks to bite into the image-object FIG. 4. In another work, created in the Cayman Islands, stingrays brushed up against paintings, attracted by the squid ink and blood that the artists had used to mark the surfaces of the work. In each of these instances, art becomes one of the triggers that serves to elicit a response from the animal – but it is also not entirely foreign to the environment in which the interaction occurs. The artists are at once instigators and, one might argue, collaborators with these animal participants.

Crucially, this process involves a double remove from the physical confines of the gallery. The first might be perceived as a rejection of culture through a flight into nature. And yet this very notion plays into a Romantic fiction tied to a centuries-old lineage of artistic production. Furthermore, even in the natural environment inhabited by the non-human species, the artists might be seen to retain their anthropic gaze, since the animals are the subjects of the initial works rather than their agents. It is the second remove that is fundamental: a recognition of the creative potential of the nonhuman. The duo’s disruption of the predictable assignment of roles between artist and nature encourages a reconsideration of their own relation to the nonhuman. Here, the significant question is not so much the physical location of art – where the work is produced – but the distinction between subject and object. In other words, what kind of material and symbolic shift does an aesthetic artefact undergo when it serves as the medium for a reversal of the terms between work of art and artist?

In these projects, Olly and Suzi are less interested in understanding the boundary between humans and animals than they are in allowing for a fluidity within artistic creation, or what Matthew Calarco terms ‘zones of indeterminacy’. Such zones designate ‘a space in which supposedly insuperable distinctions between human beings and animals fall into a radical indistinction’.14 In Olly and Suzi’s work with endangered species, both humans and nonhuman animals play a role in producing the final project: an amalgam of physical brushstrokes and bodily gestures that undermines the pre-eminence of the human. Indeterminacy or indiscernibility opens up a productive space in which to rethink the status of the Anthropos that underpins the category of the aesthetic.

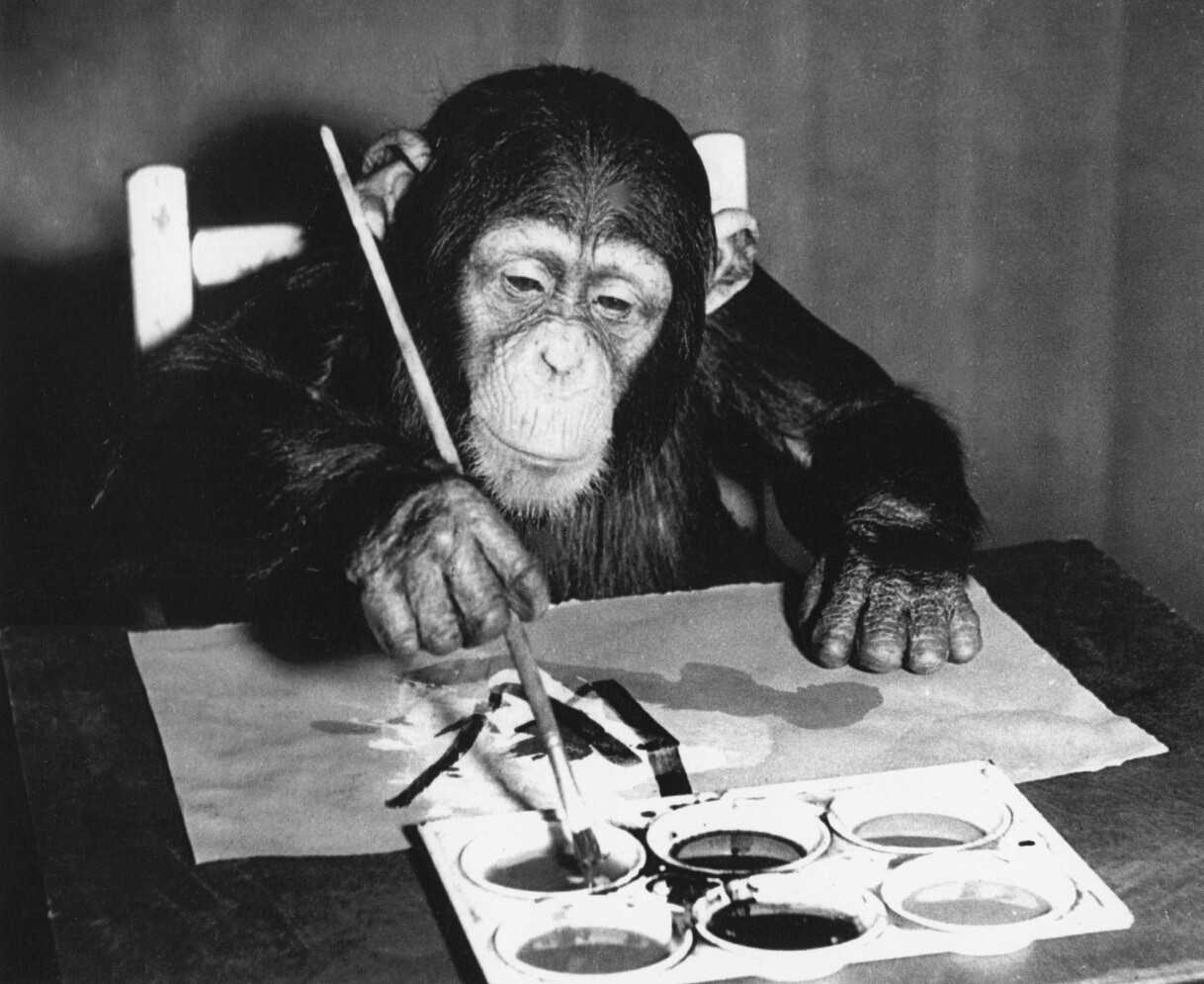

To the extent that it challenges the parameters of aesthetic experience as something confined to humans, Olly and Suzi’s work is in direct conversation with an art-historical lineage of primitivism and so-called ‘ape art’.15 In the framework of modernist primitivism, the self-conscious alignment of artists with animals or ‘animality’ expressed a desire for an art predicated on a return to the earliest conditions of creative production: that is, to a space free of the repressive effects of human culture or socialisation.16 (And indeed, to this point, A.A. Gill has compared Olly and Suzi’s paintings to ‘prehistorical rock art [. . .] images that are aesthetic as a by-product of their mystical purpose’.)17 In this schema, human consciousness is set against an animal instinct that is imagined to be operating on a purely biological level. The development of gestural abstraction in the twentieth century also gave rise to the parallel phenomenon of primate art: paintings and drawings made by chimpanzees with the assistance of human artists and ethologists.

In the 1950s scientists undertook a series of experiments that aimed to reveal evidence of ‘artistic behaviour’ in apes. The larger stakes of these studies were to determine how art emerged in the evolutionary process leading from pre-human to human life. The zoologist Desmond Morris was able to show that apes were indeed capable of producing drawings and paintings that followed a compositional logic. According to this line of research, primates demonstrate a capacity and taste for introducing formal variations that share an affinity with the pictorial concerns of Tachisme and Art informel FIG. 5.18

These experiments gave rise to a more difficult question: do apes ‘understand’ the compositional logic of painting, or is this display of aesthetic coherence a superficial or reflex response to external stimuli? As Thierry Levain has argued, apes may be able to generate complex compositions that demonstrate a ‘visual intelligence’, but their paintings constitute only passive responses to the tools and procedures that have been offered to them:

Even the chimpanzees who show the best mastery of the pictorial device as well as the strongest concentration during play and who introduce the most relevant formal variations, always follow extremely rigid rules when including a pattern in the field. And their combinatory capacity never goes beyond the one-level operation of marking a pre-existing shape (which itself can be complex) by another shape made out of a few brush-strokes [. . .] The variations may indisputably be relevant in terms of form, but they do not reveal any conscience of the form.19

In other words, apes can follow a set of formal procedures for producing a well-composed painting, FIG. 6 but they do not understand these marks as belonging to a pictorial field, a conceptual move that rests on the distinction between signifier and signified or between making marks on a surface and the implicit assertion that ‘this is a painting’. Yet such a conclusion ultimately relies on an anthropocentric notion of reflexivity that confines the aesthetic to the conscious production of signs.

Olly and Suzi’s art knowingly references a tradition of gestural abstraction often associated with primitivist art. The figurative representations of their animal subjects are executed in a gestural style that draws on the formal properties of expressionist painting, and the interventions of the animals can be seen to reinforce this aesthetic. In Suzi and Wild Dog, Mkomazi, Tanzania, for example FIG. 7, the earth-toned brushstrokes are spontaneous and almost abstract, evoking the emotional intensity of expressionism, even as they cohere into recognisable animal physiognomies. What seem to be paw prints and other marks made by the dogs might thus seem to reiterate the forms painted by the human hand. Once the initial image is created, however, the work develops to combine elements of performance and environmental advocacy in ways that directly confront questions of animal agency and intelligence, rather than presenting the animal paintings solely in relation to artistic standards set by humans.

This tension around the definition of the artist is made explicit in a project staged in the Venezuelan Llanos, in which the artists set out to produce paintings with the aid of the green anaconda FIG. 8. A species of non-venomous boa that inhabits swamps, marshes and slow-moving streams across much of South America, the green anaconda is the world’s heaviest snake and one of its longest, capable of reaching up to five metres. Assisted by a professional snake tracker, Olly and Suzi trapped an anaconda and carried it back to a ranch. There, the artists covered the underside of the snake with a natural paint mix, took relief prints of the animal and then left it to make its own marks on large sheets of paper FIG. 9. They describe the process as follows:

The anaconda slithered across two pieces of Japanese paper leaving beautiful and subtle marks, a trace of her scaly skin. After each painting, we washed the snake in the water. She was now calm, seemingly a willing partner in this collaboration. We outlined her coils and delineated her silhouette. After no more than an hour our work with the snake was complete.20

Certainly, however tempting it is to suggest that Olly and Suzi’s paintings offer an improvisatory surface for interspecies exchange, one where human and nonhuman animals ‘trade marks’ outside the normative structures of figurative painting, scientific naturalism and zoological display, their entry into already fragile ecosystems is problematic.21 In their initial preparatory actions, the artists were arguably baiting endangered species into a response or reaction.22 In this sense, the work marks an intrusion into nature. And yet both humans and animals can be seen as agents involved in an unpredictable exchange whose meaning and outcome are not always clear. The snake may be covered in green paint so that it leaves a mark, but the path it takes across the paper is its own. Moreover, although the artists set up the conditions for these cross-species encounters, they do so in ecosystems that are unfamiliar to them and, sometimes, dangerous. As they make clear, ‘tracking, painting and interacting with these animals emphasises the reality of being on the food chain’.23

This question of artistic intention, or the capacity for creativity across species boundaries, is also central to the duo’s work with great white sharks. The shark that bites into a painting fits into long-standing preconceptions about the ‘primitive’ state of nature and about animals governed by the blind automatism of pre-programmed biological needs and urges. Yet the shark that is encouraged by Olly and Suzi is also responding to what might be called creative stimuli. Against an understanding of instinct as stimulus-response, operating strictly by reflex, much recent work on animal behaviour has called attention to its improvisational capacities. As Brian Massumi notes with reference to the fast-evolving study of animal personality, ‘instinct itself shows signs of elasticity, even a creativity one might be forgiven for labelling artistic’.24 Massumi’s emphasis on the creative dimensions of animal life finds its parallel in Olly and Suzi’s efforts to make animals active participants in the production of a painting.

In these interactions art is made to inhabit a space or environment beyond that of the traditional exhibition. This is not simply art that has been produced in the ‘wild’, as in the tradition of wildlife or landscape painting and photography, nor is it an art that holds nonhuman actors accountable to human standards, as in so-called ‘ape-art’. Although Olly and Suzi’s works are exhibited in institutional spaces, to human viewers, the collaborative processes in these works at least partially unsettle the conventional boundary between animal subject and human observer/artist. The animals involved in these paintings enter into the institutional space not only as objects of study but as participants. We cannot know what the snake thinks or feels about that process, but that uncertainty is central to the work: an admission of an affective or bodily response that is not ours, not human.

Pierre Huyghe

While Olly and Suzi work in relation to an art-historical lineage outside of the institutional frame, Pierre Huyghe considers interspecies relations within the space of the museum and the discourses of art history. In his animal-centred installations, Huyghe explores the mutual transformations of cultural and biological systems, and the place of the human within them. He links these transformations to art history through his engagement both with the legacy of land art and with the authority of modern masters such as Claude Monet and Constantin Brancusi. What emerges is not a clear distinction between species – as actors, participants or subjects – but a space of instability that undermines the art-historical canon and the place customarily assigned to animals within it.

In his retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 2013–14, which travelled later that year to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA),25 Huyghe set up what one critic described as a ‘crossbreeding of art by nature, of the human by the animal, of the image by the biological and geologic’.26 The exhibition space became a quasi-natural ecosystem: a constructed location that nonetheless had its own biotic and nonbiotic drives (including the instinctual behaviours of bees, processes of decay and climatic shifts). At the end of one room at LACMA, audiences encountered Reclining Nude, the beehive-headed Max Weber replica first included in Untilled FIG. 10. The sculpture’s form and function are altered by the harvest cycle of the bee colony, its position within the art-historical canon complicated by its place within the ecological ‘mesh’ of the exhibition. Although the bees and their hive were tended by a human keeper, the insects’ actions were mostly governed by swarm intelligence: the collective behaviour of a population that self-organises and carries out collective tasks independently of the will of any single agent.27 This group mechanism contrasts with the emphasis placed on individual cognisance in humanistic frameworks of knowledge – a tension embodied here in the single human figure, the nude, whose head has been replaced with a form of nonhuman consciousness.

Also on view at LACMA was A Way in Untilled (2012), a video which resituated viewers in the site created by Huyghe for dOCUMENTA 13. Here, the uprooted oak tree in Untilled FIG. 11 introduces a further art-historical framework of the nature/culture divide, that of land art practices of the 1960s and 1970s, which aim to situate artworks in remote and seemingly uncultivated environments, or conversely to bring elements of ‘the wild’ indoors. The tree, one of the seven thousand oaks that Joseph Beuys had planted in Kassel for dOCUMENTA 7 (1982), seems to invoke a lineage of contemporary art as urban renewal or environmentalism. Yet unlike in Beuys’s project, in which a basalt stone was removed from the lawn in front of the Museum Fridericianum every time a tree was planted – a move that replaces ‘art’ with nature – Huyghe’s work is a nature-society hybrid.

The tree also bears visual similarities to Robert Smithson’s Dead Tree (1969), an uprooted tree that the artist brought into the Dusseldorf Kunstalle FIG. 12. As Philipp Kaiser and Miwon Kwon note, artists such as Smithson were ‘resistant to conventional beliefs regarding what counts as art, how it can be made and where one might find it’.28 Such artists also challenged the possibility of monumentalising nature as an autonomous sphere of existence, separate from our culturally acquired perceptions of it. Thus, in his models of Site/Non-Site, Robert Smithson theorises a dialectical, non-hierarchical relationship between here and there, inside and outside, between the geographical location of a work of art and its sculptural, photographic or text-based representations. Such an approach suggests that the anthropocentric frame, or the way in which we view nature, cannot be entirely dissolved, but it can be troubled or put into a more symbiotic relationship with the ‘natural’. Like Smithson, Huyghe troubles the art taxonomy but in Untilled does so in a multiplicative fashion: he takes what was once art, reclassifies it as nature, and assigns it to a contemporary art environment outside the walls of an art institution.

Other works within Huyghe’s 2013–14 exhibition more directly upend human systems of control, most especially those at play in the museum institution. (Untitled) Weather Score (2002), which was positioned opposite Reclining Nude, creates artificial rain, snow and fog with the aid of computer software. Here, natural and artificial systems were made to intersect with one another – so that, in an inversion of the tradition of land art, the institutional space takes on the features of the outside environment. This impulse was carried over into the Zoodrams, large aquariums containing different marine ecosystems. In Zoodram 5 (2011), a hermit crab turned a resin copy of Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse into its extemporaneous habitat FIG. 13. Like the prehistoric-looking crustaceans, the volcanic rock in the aquarium operated as a marker of ‘deep time’, the immense scale involved in measuring geological and evolutionary processes. The work alludes both to a period before humans and to an imagined post-extinction world, bringing nonhuman timescales into collision with the temporal rhythms of the art institution, such as opening and closing times, exhibition calendars and scales of human perception.

A subsequent version of the Zoodrams project, also included at LACMA, Nymphéas Transplant (4–18) FIG. 14 consists of aquariums housing the plants, fish, amphibians, crustaceans and insects that were found in Monet’s garden at Giverny. The tank was equipped with a lighting system that fluctuated in eight-hour intervals. While based on natural rhythms or cycles – Huyghe drew on the ‘climatic data’ of Giverny between 1914 and 1918 – the timing of these intervals functioned independently of the actual external conditions (the time of day or the season), adhering instead to a set of algorithms. If this disjuncture serves to trouble a ‘cultural climatology’ carried out through the analysis of works of art – a move that contrasts evidence found in paintings by John Constable, Monet and others with data-driven climate models29 – it also points to one of the problems of climate science. Unlike the weather, climate – the aggregation of atmospheric conditions over time and space – is an abstraction that can never be experienced first-hand. This takes on acute significance in an era marked by both the heightened effects of global warming and a ‘post-truth’ information environment that serves to invalidate ‘hard-won evidence that could save our lives’.30 In line with Huyghe’s longstanding disruption of exhibition protocols, these aquariums should be seen as ‘living systems’ that are not governed by human notions of time or (most especially) the temporal logic imposed by the modern museum. As the artist points out, each work constitutes ‘an evolving organism, generating itself in a continuous ever-changing transformation, whether biological (with instinctive behaviour) or mechanistic (driven by algorithms with encoded living presence and process)’.31

This rejection of human-centered perception, especially within the art-historical context, is made most explicit in Huyghe’s ironic incorporation of Human, a white Ibizan hound with one of its legs painted fluorescent pink FIG. 15.32 The dog wanders the galleries, seeming at once largely indifferent to the presence of people (much like the bees) and somehow performative (like the ice skaters within the same retrospective, who took to the frozen stage on a set schedule).33 Museum visitors are instructed to ‘refrain from touching, petting or otherwise disturbing her’.34 In this way, the work frustrates the human desire for certain forms of interspecies interaction. Without a clearly defined relationship established between Human and the visitors, her presence within the space is unsettling. A series of questions arise: who has agency in this situation?; what are the relative positions of the animal and the human in the gallery?; what are the institutional and cultural protocols that determine their interactions?; how do those interactions challenge the boundaries of the institution?

The name Human, of course, suggests either a proclamation of ownership or an anthropomorphic projection. Some of the discomfort felt by viewers arose from an uncertainty about whether or not to perceive the dog as yet another actor playing a part. It seemed impossible to tell how much, if at all, her actions were scripted by instinct or training. In this regard, the artist’s decision to include this particular breed in the exhibition was telling: considered to be one of the oldest dog species, the Ibizan hound was most likely transported from Egypt (where tombs dating from 3,000 BC show identical morphology to the hounds of today) to the island of Eivissa by the Phoenicians.35 As Huyghe has written, through this breed ‘you can follow and trace Homo Sapiens’ routes of navigation, trade and exchange’.36 The hound is already coded as deeply entangled in human history. That history underscores a central point of the display: that dogs are thoroughly domesticated and have been profoundly shaped by their human ‘masters’. Yet if Human’s actions are scripted, or shaped by humans, then so too are the actions of the two-legged participants in the exhibition. Indeed, the coupling of Human with Player (2010) FIG. 16 – a man in an LED mask that trails the hound – seemed to suggest that the power dynamics of human-animal entanglements could go in both directions. With Player’s face obscured by a digital screen FIG. 17, it is unclear what kind of posthuman subject was being imagined and what role it might have to play within the exhibition.

To date, much of the discussion of this work has revolved around the ethics of using a live animal in a work of art. When Human was exhibited in Los Angeles, LACMA took pains to communicate to visitors that the animal was a rescue dog and that its protruding breastbone and ribs were not signs of malnutrition but typical of the breed’s general appearance. Moreover, on its blog the museum publicised the fact that the animal had a private resting area and went home each night with her handler.37 This pre-emptive move is indicative of a wider preoccupation with animal rights that extends across the fields of behavioural science, biology, ethics, law and the humanities. Recent efforts to grant legal rights to animals are premised on the argument that certain species possess capabilities that are fundamental to all persons: self-consciousness, rational agency, emotional complexity and the capacity to learn and transmit language. Thus, for the founders of the Great Ape Project, a worldwide effort to extend the rights commonly afforded to humans to chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans, the aim is to establish human and nonhuman animals as a ‘community of equals’ who share basic rights.38 Yet this model of animal rights remains at odds with a strand of animal studies that questions a perspective that perpetuates the centrality of the human as a measure of the respect due to another species.39

Such frameworks based on animal rights do not address some of the more intractable problems posed by Huyghe’s work – conundrums that get much more to the fraught definitions and uneasy boundaries of the ‘animal’ actor in relation to the ‘human’ artist and audience within the exhibition. The coupling of Human and Player calls to mind what Donna Haraway terms a ‘becoming-with’ other species or an acknowledgment of ‘the flourishing of significant otherness’.40 If Human is a product of millennia of human breeding, then so too are the human participants. Moreover, if we are to admit the cognisance and agency of the human participants, then we must also recognise the alterity of the animal species. As in the works by Olly and Suzi, the animals here are brought into the art-historical tradition in such a way as to destabilise the rules and species relations of the anthropological gaze.

Contemporary art beyond the anthropological machine

Drawing a link between humanism and the institution of speciesism, the curator Anselm Franke has argued that ‘apes and monkeys have been held prisoners of the mirror that they represent for us’.41 That is to say, our understanding of them is based on our perception of ourselves, what we see in the mirror. This mirror is also what prevents human access to an ‘unobstructed primate nature’ underwriting ‘the illusion of culture’.42 Caught in our own reflections, we cannot see what sits on the other side of the glass.

Franke does not directly extend his analysis to the boundaries of the art establishment, but through the work of Huyghe and Olly and Suzi, it is possible to address what it might mean for animals to emerge from behind this web of signification. The interspecies works of art discussed here create an uncertain and indeterminate space within what Giorgio Agamben describes as the ‘anthropological machine’, the various cultural, scientific and philosophical discourses used to distinguish humans and animals through a dual process of inclusion and exclusion.43

Although there is no way to completely step outside of the human gaze, Huyghe and Olly and Suzi begin to open up art-institutional spaces wherein some of the boundaries between nature and culture can be disrupted. They engage directly with art-historical lineage to unsettle the terms through which it has been conceptualised: the humanist sculptural tradition is subsumed into animal swarm intelligence; abstract expressionism is redefined to include the pawprints of wild dogs; and land art is explored as a nature-culture hybrid. In works marked by animals that hang on gallery walls, or in the unscripted roaming of Human within an exhibition space, the artists confront the defining limits of the art museum: its gaze (implied to be human); its subject (implied to be other, either human or nonhuman); and the hierarchies on which those categories rely. To give the animal a position in the art institution, a role that is not that of the observed, is to contemplate the unstable and indeterminate relations that sit beyond entrenched distinctions of nature/culture and artwork/museum.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Christie Harner and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.