When We Were Monsters

by Maximiliane Leuschner

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 28.04.2022

Spanning the four floors of Haus Mödrath – Räume für Kunst Kerpen, a repurposed nineteenth-century mansion near Cologne, When We Were Monsters is not only the largest exhibition of work by James Richards (b.1983) to date, it has also been curated by the British artist himself. Richards’s tangled methodology transcends the distinct professions of artist, archivist, composer, curator, editor, film-maker and producer. He mines found content, drawing on a broad range of accessible sources, such as internet streams, television clips and artists’ footage, which he compiles, samples and edits, before arranging into digitally collaged slide shows, exquisite-corpse-inflected moving image and, more recently, sculptures and installations.

Applying the traditional artist-as-curator genre to a retrospective might result in a fretted megalomaniac ego-trip. However, Richards has sensitively arranged old and new work – from earlier films, such as the two-screen video projection Not Blacking Out, Just Turning The Lights Off (2011) and the Turner Prize-nominated Rosebud (2013) to more recent sculptures and mixed-media installations, including Tenant 2 FIG.1, Internal Litter FIG.2 and the site-specific Das Zimmer der toten Fliegen (The room of dead flies) (2021) – alongside complementary works by ‘kindred’ artists, such as Tolia Astakhishvili (b.1974), Albrecht Becker (1906–2002), Isa Genzken (b.1948), Margarethe Held (1894–1981), Anne McGuire (b.1963), Rachel Reupke (b.1971) and JX Williams, the pseudonym of Richards and the artist AA Bronson. Characteristic of his connective process, Richards has returned to many artists and works of art from his previous curatorial projects. His arrangement is careful, highly edited and relies on the remote setting of the privately owned stately home to create an intimate and honest display, which manifests as brutal, provocative and seductive.

Like the verbs ‘to demonstrate’ and ‘to reveal’, the word ‘monster’ derives etymologically from the Latin ‘monstrare’. Its inclusion in Richards’s exhibition title is indicative of two convergent themes: technology and its abstract and, at times, medical or scientific gaze; and technology’s sentient limits, the intimacies beyond the frayed edges of individual subjectivity. The exhibition begins with Adrian Hermanides’s Alms for the Birds FIG.3, one of the prominent non-digital works in the show. Scattered over the gallery floor are the many intimate belongings of an unknown man, including a cache of photographic test strips, a worn leather mattress, a cheap plastic poncho and a tube of lipstick. The arrangement is evocative of both a sacrificial offering and an authorless archive of desire. Haus Mödrath served as a maternity home in the 1920s, a home for refugees during the Second World War and an orphanage in the 1950s. Hermanides’s configuration recalls this complicated past, as well as the trope of the domestic tenant, which was the central theme of Lodgers, Haus Mödrath’s inaugural exhibition in 2017. The show explored the idea of the building as an embodiment of those living inside it and traced the history of the mansion and its occupants through contemporary works of art.1

Shown on the first floor, JX Williams’s Untitled (Bull Chain) FIG.4 comprises a circle of what Richards refers to as ‘festively gay paraphernalia’ (p.64). Inspired by the decorative chain above the Bull Bar, an all-hours space in Berlin for drinking, group sex and cruising, the work includes a police truncheon, handcuffs, cowbells and tambourines, and a builder’s yellow hard hat. The work was first shown in the group exhibition Ache at Cabinet, London, in 2018, also curated by Richards. At Haus Mödrath Untitled (Bull Chain) is shown next to a wooden pavilion that houses intimate and performative photographs by Becker, which document his acts of self-tattooing, masturbation and body modification. In 1935 Becker was jailed for three years by the Nazi regime for indulging in homosexual acts, thereby violating Paragraph 175. After his release, he began tattooing his body during military service on the Eastern Front and discovered the auto-erotic sensation of ink on skin.

This is followed by the moving image work When We Were Monsters FIG.5, which stems from Richards’s ongoing collaboration with the Canadian artist Steve Reinke (b.1963). Working with each other remotely, across the Atlantic, the artists maintain a collective archive of found and self-shot footage, sound and text. During the first COVID-19 lockdown this coalesced in the film that lends the exhibition its title. The point of departure for the work was a bank of clinical footage of infections, deformities and morbid injuries, which was first given to the artist Gretchen Bender by a plastic surgeon in the early 1990s. Bender went on to use it in a video work for the choreographer Bill T. Jones in 1994. Richards and Reinke’s film juxtaposes Bender’s footage with cartoon images and animations of dancing clowns, passages from Aristotle’s writings and photographs of Ivan Pavlov’s dog experiments in the late nineteenth century.

Meanwhile, tender, drawn out lines from Judy Grahn’s poetry, recorded by the vocal trio Juice for Richards’s Radio at Night FIG.6, echo throughout the first floor rooms. Interspersed with melodious electronic music samples, it almost dominates the nearby works, including four spiritual Dämon portraits by Held and the quivering silhouette take on a candlelight dinner in Reupke’s video Deportment (2011). Radio at Night features sequences from an erotic film about an imagined Venetian costume party; news broadcasts; negative footage of seagulls flying over the ocean; and imagery of pigs and fish being processed at a food facility. Also included in the Lodgers exhibition, it was then installed in the lower-ground bedroom. Radio at Night summons desire, the dreamworld and the psyche as the emotional undercurrents of the bedroom – arguably the most intimate room in any home – through its haunted, sinister amalgamation of collaged images and sounds.

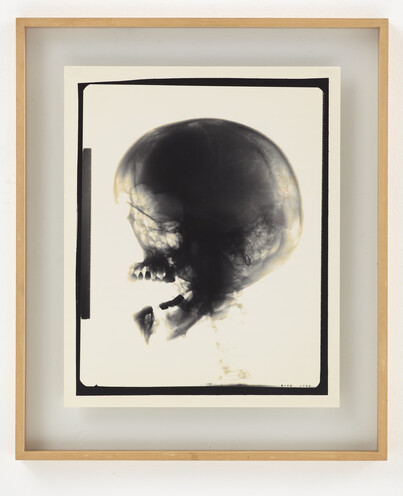

The exhibition also includes a number of site-specific works. Richards’s Room of dead flies derives from the accumulation of dead flies and other small insects on the windowsills of Haus Mödrath; they will not be cleaned for the duration of the exhibition. His lightbox installation Internal Litter features a selection of collaged and photographed scrapbook prints that have been inserted as negatives. They include X-radiographs, found imagery, smartphone snapshots and images from second-hand books that also served as material for SPEED at the Künstlerhaus Stuttgart in 2018 – a major commission with the film-maker Leslie Thornton that also characteristically included ‘a show-within-a-show’.

The medical references and clinical themes in the exhibition have been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic and successive lockdowns. For example, Genzken’s X-Ray FIG.7 reveals the decorative elements of her medical brain scans from a dire period of illness and hospitalisation. This is installed in dialogue with Richards’s Rosebud, which includes close-ups of art books in a Tokyo library, where the genitalia have been scratched out to comply with censorship laws. McGuire’s five-minute video When I Was a Monster (1996) is an exploration of the life-altering injuries she sustained after a severe accident. McGuire sits naked in front of the camera and moves her wounded body, her broken wrist cased in orthopaedic restraints. McGuire originally made the work as a record of her injuries, and it was only after months of healing that she considered the video a work she might share. Our reception of these works is further informed by the intrusion of witnessing such private examinations – albeit ones that are made public.

In When We Were Monsters the forensic gaze is omnipresent. It permeates the exhibition not only in the subject-matter of the selected works, but also in their modes of representation: X-radiographs, lightboxes, digital slides, photographs and films. And yet Richards’s considered curation augments a purely clinical perspective, drawing also on spiritual and personal intimacies. Compositely, it is both confessional and dispassionate, it merges the public and the private, juxtaposing the beautiful alongside the abject.

Exhibition details

Footnotes

- See: exh. cat. Aftermieter/Lodgers, Kerpen (Haus Mödrath–Räume für Kunst) 2017. footnote 1