Walking in 2018

by Jessica Santone

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 31.01.2019

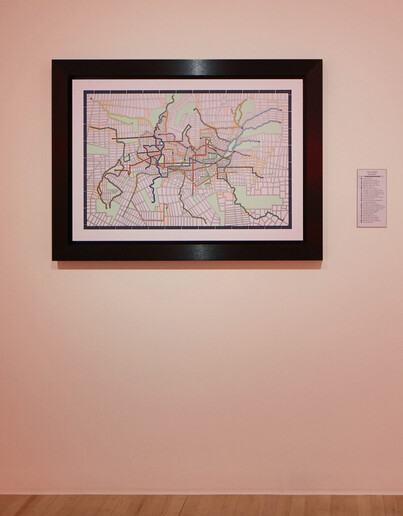

The exhibition Other Walks, Other Lines at the San José Museum of Art begins with a subtle yet powerful print by the Bay Area artist Lordy Rodriguez. Commissioned for the show, City of Marches FIG.1 sets the tone for an exhibition centred on the intersection of bodily movement, political power and the everyday. Rodriguez’s piece overlays routes of historical protest marches, pilgrimages, and death marches from various places onto the map of a single fictional city, using the vernacular of Google Maps navigation. The city is broken by these marches, its gridded streets realigned by their paths, but it is also stitched together. The image memorialises these marches, but grafted onto an imaginary city their paths also suggest future trajectories.

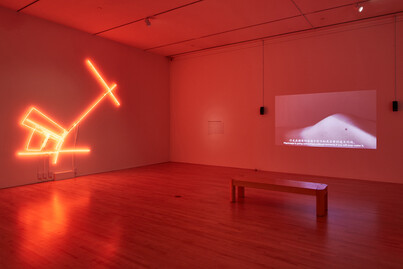

One key impetus for the show is the new era of civic participation in the streets in the United States – from numerous marches in support of Black lives, starting with the Million Hoodie March for Trayvon Martin in New York City in 2012, to the largest march in US history with the Women’s March in 2017, which was held in dozens of locations around the world. Movements today mobilise virtually on social media, but it is through walking together in real spaces that their discourse transforms into a forceful demand for recognition. The exhibition FIG.2 assembles works made since the 1990s that have made use of walking – whether as pilgrimage or ordinary practice, with others or in solitude. This arrangement – divided into four themed sections with an addendum on a separate floor, ‘Other Walks: Gabriel Orozco’ – encourages reflection on more recent politics of bodily participation in the streets. Yet two events concurrent with the opening of Other Walks, Other Lines added weight to the works on view and drew new lines between objects across its rooms.

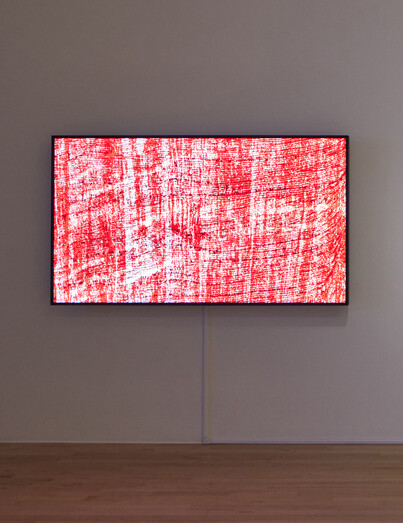

First, one of the dominant stories in the American media towards the end of 2018 was the pilgrimage of Central American refugees to the United States-Mexico border to seek asylum. Decried by white supremacist politicians as an emergency threatening national sovereignty, it prompted the unwarranted deployment of the US military to the border ahead of the midterm elections of 6th November. That same week, as the exhibition opened, news was broadcast of families walking slowly through Mexico, still thousands of miles from the border, moving as a group for their own protection. It would be impossible not to think of their march when looking at the works in the show – particularly the Iraqi-Kurdish artist Hiwa K’s Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) FIG.3, an eighteen-minute video of a migrant balancing a tower of mirrors on his nose and using it to navigate a foreign land, or Untitled 12 (Panorama) (2015) by the Israeli artist Michal Rovner, a looped animation of tiny black bodies moving like blood cells along paths through a red and white landscape FIG.4. Other works meanwhile resonated with probable causes for or effects of emigration, such as Clarissa Tossin’s subtle Ladrão de Tênis / Sneaker Thief (2009), a sculpture of thirty-six plaster casts of worn shoes made in response to murders of people for their sneakers in Tossin’s native Brazil, or the video documentation of the Guatemalan artist Regina José Galindo’s performance ¿Quién puede borrar las huellas? (Who can erase the traces?) Guatemala City (2003), in which Galindo made footprints from a large bowl of human blood that she carried along a route from the National Palace to the Constitutional Court as a protest against the presidential candidacy of the former military dictator Efraín Ríos Montt, or finally the performance documentation of San Francisco artist Ana Teresa Fernández’s Ice Queen (2011), in which the artist calls attention to the bodies of women in marginalised spaces such as sex workers as she stands in a gutter in a melting pair of stilettos made of ice. One of the strengths of this exhibition is its international scope, and each of these works speaks to the urgent intersection of migration and global political violence in the twenty-first century.

The other event related to walking in 2018 was more local, and seemingly more temporary, but had a dramatic physical effect on the inhabitants of the Bay Area. Visiting the museum mid-November was an occasion to duck out of poisonous air and briefly remove one’s respirator mask. A few hundred miles away, the Camp Fire burned over 150,000 acres in what would be the deadliest wildfire in Californian history, one likely accelerated by the effects of climate change. Toxic smoke drifted into the Bay Area and lingered for ten days while the state waited for the late start of the rainy season. Eyes burned after spending a few minutes outside. Walking in and around San José was a different prospect in November 2018 than the exhibition’s curators, Lauren Schell Dickens, Rory Padeken, and Kathryn Wade, could have imagined when planning the show. A week of masked pedestrians seemed to portend future California autumns. In this atmosphere, the playful conceptual project of the Cuban artist Wilfredo Prieto takes on new meaning. His Walk (2000), a houseplant taken for a walk in a wheelbarrow, reads less like an absurdist gesture and more like a rescue mission FIG.5. Upstairs, in the room devoted to Gabriel Orozco’s photographs and video works FIG.6 FIG.7, compositions of everyday things that humorously reconfigure spatial depth or object relations function as reminders of our excessive consumption: a pile of shoes hung on an outdoor wall (Shoe Shop; 1995/2016), an overturned umbrella (Darth Vader; 2014), and the nightmarish montage of commercial products in a supermarket shot from the low perspective of a dog’s back (Before the Waiting Dog; 1993). Ours is an era of stuff, things made and laid and waiting – stuff that, in its abundance, serves to highlight our vulnerability.

As critics from Michel de Certeau to Rebecca Solnit have reminded us, the everydayness of a walk is always political.1 From the perspective of November 2018, walking is often a matter of life or death. Other Walks, Other Lines makes this apparent with a host of global contemporary examples of performance art and performative art – works that inspire some stillness from the visitor to consume their movements. For those motivated to walk instead, the exhibition includes two take-away cards by Lordy Rodriguez that invite the visitor to step outside and follow the routes of two local protests from earlier in 2018, the anti-gun violence March for Our Lives and the Women’s March, to commemorate and to recontextualise these events. On 21st and 23rd February, the Kenyan-born Canadian choreographer Brendan Fernandes will present Inaction (2018), a site-specific dance performance by the New Ballet Studio Company, which promises to briefly reconfigure how visitors walk through the museum’s galleries and prompt reflection on how architectures, institutions, and norms control bodily movement.

Exhibition details

Footnotes

- M. de Certeau: The Practice of Everyday Life, transl. S. Rendall, Berkeley 1984; R. Solnit: Wanderlust: A History of Walking, New York 2000. footnote 1