Wael Shawky’s double estrangement

by Nat Muller

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 20.07.2022

The Egyptian artist Wael Shawky (b.1971) is a master storyteller. In his multifaceted practice, which comprises video, drawing, painting, installation and performance, he seamlessly traverses histories, geographies and mythologies, always adding his personal take on the past and making it strange. Estrangement, whether enacted through visual, performative or linguistic means, might be Shawky’s most effective device in throwing the viewer slightly off kilter. For example, his use of black-and-white or negative film for his videos; the citation of historical and art-historical references in drawings and wood carvings that are twisted into the fantastical through the incorporation of fairy-tale animals; the introduction of child actors or puppets as performers; and perhaps most consistently, his use of Fusha, classical Arabic, which lends his work a formal and archaic quality. These tactics revaluate frames of reference and ask where factual narration ends and fiction begins.

The solo exhibition Dry Culture Wet Culture at M Leuven, brings together three main projects that have defined Shawky’s practice: The Cave (2004–05) in which he recites Qur’anic scripture in contemporary consumerist environments; the film trilogy Cabaret Crusades (2010–15), an interpretation of the Crusades from an Arab point of view; and The Gulf Project Camp (2019–ongoing), which considers the history of the Arabian Peninsula from the seventeenth century until the present. These bodies of work pivot around processes of transformation and transition, ideas that Shawky became fascinated with at an early age due to a childhood spent in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, at a time when oil was rapidly changing socio-economics in the Gulf.1 The friction between old and new ways of life lies at the heart of the work shown at M Leuven. The exhibition’s title is derived from Shawky’s understanding of ‘dry culture’ and ‘wet culture’ as a shift from nomadic desert dwellers living with the aridity of the desert to sedentary communities in which the ‘wet’ conditions of irrigation and agriculture take central stage.

Dry Culture Wet Culture opens with the vast architectural intervention The Gulf Project Camp: The Wall #2 FIG.1: a large graphite-covered wall snakes through the space, resembling a city or fortress wall, on which the artist has affixed textiles akin to those of Bedouin tents. Here the difference between a nomadic lifestyle vis-à-vis a sedentary one is materialised in a literal way. This work is further marked by the interplay between boundaries and oppositions: the black hue of the installation versus the pink walls enveloping the space; the soft fabric of the tents versus the hard surface of wall structure; and the pliability of textile versus the stasis of the built environment. Yet what is perhaps most striking is the barrier this installation puts between the viewer and work of art, frustrating not only visual but also interpretational accessibility. It is an odd entry point to an otherwise rich and multi-layered exhibition in which the spiritual, mystical and imaginary play an important role. The latter is a foundational aspect of Shawky’s practice but in curatorial framing often yields territory to more socio-political narratives.

Shawky’s most complex critiques of the perception of history and society lie precisely in his otherworldly magic and tactics of estrangement. A work highlighting this particular characteristic of his practice, such as Cabaret Crusades or the body of work Al Araba Al Madfuna (2012–19), which is not shown at M Leuven, might have made for a stronger opening. The installation Drama FIG.2, an additional iteration of The Gulf Project Camp presented on M Leuven’s top floor, is much more convincing at demonstrating Shawky’s ability to tell the past, as well as muse on the future. The installation, a room-size model of an abstracted urban landscape covered in asphalt, creates a mesmerising dialogue with the panoramic view offered by the museum’s large windows. Close inspection of the work reveals that some of its structures – could they be mosques, churches, clock towers, high-rises? – have collapsed. The installation incorporates the actual city of Leuven through the windows and reflects a speculative, and rather ominous, image back at us. Might this be the end point of techno-modernity for the urban landscape: a city suffocated under thick black bitumen where all colour and difference are blotted out? It is a disturbing proposal, but the work never fully takes the viewer to a dark place; it remains playful and poetic.

These two works, which bookend the exhibition, not only disrupt ways of seeing and confuse the inside with outside, they also scramble chronologies, blurring the past with the present and the future. This is echoed in the film Cabaret Crusades: The Secrets of Karbala FIG.3, which focuses on the Fourth Crusade (1202–04) and Pope Innocent III’s quest to recapture Jerusalem from Muslim hands. The Secrets of Karbala is the final film in Shawky’s epic trilogy and is preceded by The Horror Show Files (2010) and The Path to Cairo (2012), drawing respectively on the First Crusade (1096–99) and the Second Crusade (1147–49). Shawky based his film scripts on the writings of twelfth-century Arab chroniclers, such as Ibn al-Qalanisi, Ibn al-Athir, Usamah Ibn Munqidh and the more contemporary book The Crusades through Arab Eyes (1983) by the Lebanese author Amin Maalouf. Importantly, he adds his own fictional elements to these historical accounts, thereby confusing the distinction between written history and fictional imaginary and questioning the construction of myth.

As in the two previous films, the cast of historical characters consists of marionettes, this time beautifully crafted puppets fashioned out of Murano glass, their features based on the collection of African sculptures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The artist’s use of Murano glass is not a coincidence; as the film and visual culture scholar Laura U. Marks points out, Venetian glassmakers learned techniques from Arab artisans and from trade with the Muslim world.2 In addition, the Fourth Crusade set out from Venice, which adds an additional historical reference to Shawky’s narrative. What follows is an intricate entanglement of political intrigue and murder in which not only historical characters but also glass dragons, murderous dogs and wailing camels propel the narrative with estranging, translucent and magnificent theatrics. The display of the puppets FIG.4 alongside the film is one of the highlights of the exhibition – their alien appearance and string mechanism waiting to be activated. Shawky plays on this tension between stasis and action and centres his attention on the moment of transformation when possibility is up for grabs.

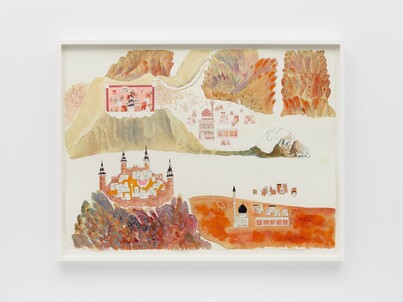

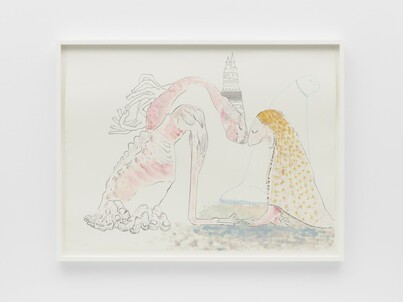

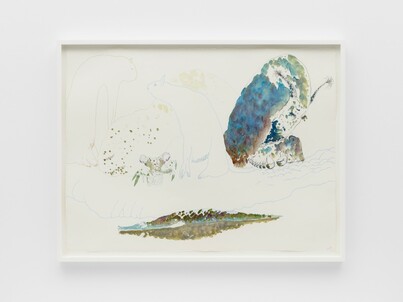

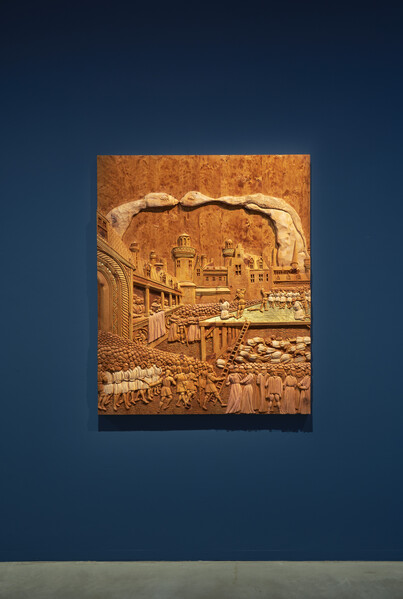

This notion of potential, in which the inanimate turns animate, is best articulated in the series of delicate drawings FIG.5 that accompany Cabaret Crusades. Whereas the film is a thoroughly scripted and meticulously produced result of a close collaboration with puppeteers, set designers, musicians, camera operators, light technician and editors, these drawings demonstrate Shawky’s artistic whimsy at its freest and most imaginary. Here beautifully strange and magical creatures morph into the landscapes of Jerusalem, Damascus, Antioch, Tripoli and other sites FIG.6: camels blend into mountains, a giant crab forms the base of a palm tree, giants wearing cityscapes as headdress conduct a dance of courtship FIG.7 and feline behemoths grow from the earth FIG.8. Shawky’s hand is loose here, staining some parts of the drawing with vivid colour, while leaving other parts blank. It is in these gaps of speculative becoming that Shawky’s transformative gesture is strongest and the critique on how – and from whose eyes – history is told resonates most forcefully. So too in Shawky’s Cabaret Crusades carved wood reliefs, inspired by existing paintings on the Crusades by European artists, such as Claude Jacquand’s The Capture of Jerusalem by Jacques de Molay in 1299 (1846), Jean Colombe’s After the capture of Acre by Bourges 1189 (1475) FIG.9 and Tintoretto’s Capture of Constantinople (1580). Shawky stays close to the original works but introduces his wondrous beasts and as a result radically shifts the narrative into something far stranger and more ambiguous.