Richter's windows in Tholey Abbey

by Sarah Messerschmidt

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 10.06.2020

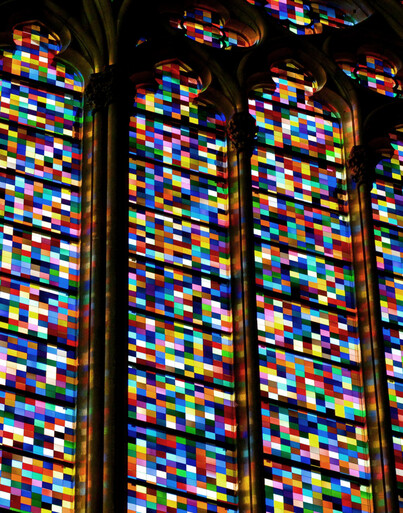

When Gerhard Richter was invited in 2009 by Bernhard Leonardy, a concert organist in Saarbrücken, to design three stained-glass windows for the choir of Tholey Abbey (the Benedictine Abbey of St. Maurice in Tholey, Saarland, which dates to the early seventh century and is considered to be the oldest monastery in Germany),1 he was hesitant to accept. He had taken on a similar commission for Cologne Cathedral in 2007, designing its large ‘pixelated’ south-facing Domfenster FIG.1,2 but believed himself to be too old now, the scale of the project too large. Leonardy, along with the community of thirteen monks who currently reside in the abbey, ultimately convinced him: the abbey church was to undergo extensive renovation, and Richter’s windows were to be among its crowning artworks. The windows are scheduled to be unveiled in September, and despite a global halt to most non-essential activity, the commission appears to be moving ahead at pace.

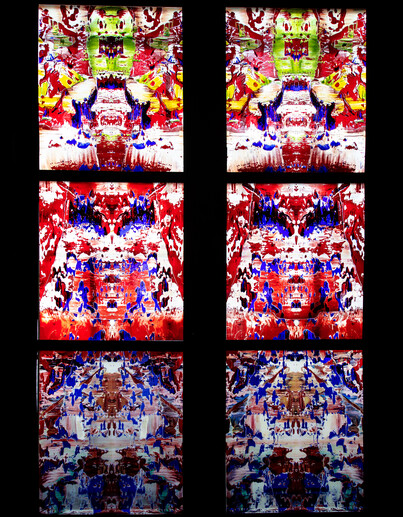

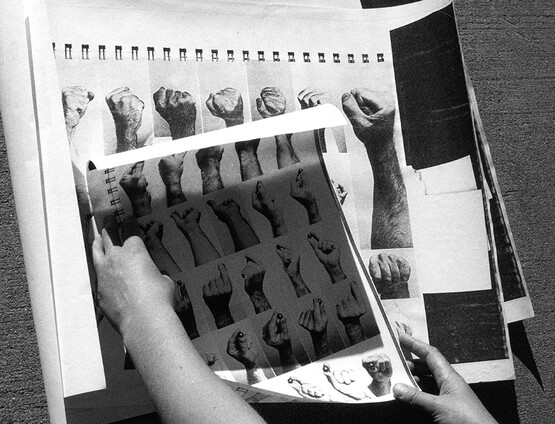

Richter’s designs for the Tholey windows can be traced to two earlier projects: Abstraktes Bild (CR 724-4), a painting from his series Abstract (1990–94), made using his ‘squeegee technique’ in which areas of wet paint are smeared horizontally across a canvas to blend in Rorschach-like markings; and his later artist book Patterns: Divided, Mirrored, Repeated (2011), a compendium of images developed from Abstraktes Bild (CR 724-4), which was divided and subdivided into thousands of smaller units to generate extraordinarily detailed patterning. Richter was reportedly working on the book when the call for the Tholey commission was made, and the windows are developed from this visual experiment, following the principle of ‘divide, mirror, and repeat’.

Whereas the artist book gradually subdivides each unit into impossibly tiny segments, shifting away from the earlier chance method by shrinking, condensing and multiplying layers of pattern until the final pages of the book have flattened each vertical strip into horizontal lines of smooth colour, the windows appear instead to have enlarged single vertical units, such that their intricate patterning fills entire panels of glass FIG.2. In vibrant arabesques that cascade the length of each window, the window designs are rendered in bold primary colours, with a kaleidoscopic effect that is vaguely suggestive of textile motifs or forms found in the natural world FIG.3. These effects are as much a byproduct of the earlier squeegee technique as the mirrored patterns found in the artist book, and the principle of chance is thus fused into glass, despite the process requiring incredible technical control. The windows have not yet been fully installed but the anticipated result, in a combination of painted and handblown glass, is a triptych of windows that will bathe the abbey’s altar in a glow of light and colour FIG.4.

Christian beliefs and practices have found expression through visual art for centuries. The use of stained glass, in particular, reached its apex in medieval Europe when it was produced to adorn church windows, often illustrating narratives from the Bible and the lives of saints, or to otherwise demonstrate the ‘performance of devotion’.3 As visual aides, medieval window designs were predominantly representational, although their interpretation would have required at least some comprehension of the intellectual material to which they gave form. Regardless, medieval art and the practice of medieval religion were indistinct, and the interpretation of stained glass would have already been contained within the ‘devotional framework’ of religious practice.4 Windows were not simply works of art for individual contemplation, but elements of a larger structure in the fulfilment of religious duty.

Given the historical function of medieval stained glass, it might seem surprising that the patrons and Richter would choose abstract subjects for the Tholey windows. Yet, stained glass has a significance that goes beyond the subject-matter it depicts: it is the medium through which divine light materialises. Famously, Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis remarked that the new east wing of his abbey church would shine ‘with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows’. He commented that the effect of light passing through coloured glass was ‘urging us onward from the material to the immaterial’, thus representing the link between matter and spirit, or earth and Heaven, instigating spiritual contemplation that is stimulated by the senses, rather than the intellect.5 If profound spiritual enlightenment can be aroused by these abstract and atmospheric qualities (the cohesion of windows with the surrounding architecture, the lively effects of natural light through glass) the possibility for abstract expression in religious art is broadened, making room for a spirituality that is not always fostered by images or narratives. It seems likely that this is the sentiment upon which the Richter commission was built.

Richter was a strategic choice for Tholey Abbey, owing to his notoriety in art circles, rather than one driven by the artist’s commitment to expressing religious doctrine. Dismissing possible interpretations of a devotional intention in his work, Richter claims that he designed the the windows ‘not to the glory of God, but to comfort the viewer’.6 He cites the laws of chance ‘as an overwhelming [universal] power, not divine providence’.7 Nevertheless, the Benedictines of Tholey hope that via the transcendent quality of light streaming through coloured glass, the windows will both convey and inspire religious faith to a modern, secular, art-consuming public (as Julian Barnes writes, ‘I don’t believe in God, but I miss Him’)8.

There is a notion that in order for the church to maintain relevance in the modern world, it must detach itself from rigid customs, striking a balance between conservation of tradition and adaptation to societal change. In total, thirty-four new stained-glass windows have been commissioned for the abbey’s renovation. Thirty-one of these are pictorial renderings of biblical scenes by the Munich-based artist Mahbuba Maqsoodi, who won the opportunity to work with the abbey in a competition FIG.5 FIG.6.9 By including three by Richter, the abbey reconfigures the site of ‘pilgrimage’ to accommodate the modern art enthusiast, drawing visitors to Tholey beyond its typical demographic. The model for this follows from the Cologne Cathedral, as well as the Cathédrale Saint Étienne de Metz, the latter of which houses stained glass windows by artists Jean Cocteau and Marc Chagall.

The place of religion in contemporary art is an unstable one – most often it is held up as an object of satire or scrutiny, even considered categorically distinct. It is rare that contemporary art lends itself to religion, to occupy a place of worship, for instance, and indeed to bolster that very activity. James Elkins – who opens his book decrying ‘the self-satisfied Leftist clap-trap about “art as substitute religion”’ – writes that when modern, and later contemporary, art made a formal break from conservative and traditional values, it no longer interpreted religious subjects in earnest.10 Although Richter’s window designs can’t be said to do the serious work of Biblical interpretation – that work has been left to Maqsoodi, a Muslim artist with a refreshingly open perspective on world religions – his participation in the project has a clear directive: the church continues to decline, and its own salvation comes with reengaging and re-inspiring a general public in the Christian faith. Whether this means that contemporary art is the ideal bridge between the church and contemporary society remains to be seen in the responses of visitors to the abbey in the coming months and years.

Footnotes

- The earliest documents that mention the abbey’s existence date to 634 AD. See K. Brown: ‘The inexhaustible Gerhard Richter will design new stained glass windows for Germany’s oldest monastery’, Artnet (21st August 2019), available at https://news.artnet.com/art-world/gerhard-richter-church-windows-1631488, accessed 29th May 2020. footnote 1

- The central window in the Cologne Cathedral, which measures twenty-three by nine metres, is made up of approximately 11,500 square panes of coloured glass. Many people opposed the non-figurative design of the window, believing it to be unsuitable for a cathedral. See M. Solley: ‘New stained glass is coming to Germany’s oldest monastery.’ Smithsonian Magazine (23rd August 2019), available at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/gerhard-richter-set-design-stained-glass-germanys-oldest-monastery-180972986/, accessed 4th June 2020. footnote 2

- E. Carson Pastan: ‘Glazing medieval buildings’ in C. Rudolph: A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe, Hoboken NJ 2019, p.641. footnote 3

- P. Hardwick: ‘Making light of devotion: The Pilgrimage Window in York Minster’ in idem. and S. Hordis, eds: Medieval English Comedy, Turnhout 2007. footnote 4

- E. Panofsky and G. Panofsky-Soergel, eds: Abbot Sugar: On the Abbey Church of S.-Denis and its Art Treasures, transl. E. Panofsky, Princeton NJ 1976, pp.75 and 101. footnote 5

- ‘Gerhard Richter im Interview: Kirchenfenster zum “Trost der Betrachter”’, RP Online, (27th August 2019) available at https://rp-online.de/kultur/kunst/interview-mit-gerhard-richter-kirchenfenster-zum-trost-der-betrachter_aid-45374545, accessed 4th June 2020. footnote 6

- Ibid. footnote 7

- J. Barnes: Nothing to Be Frightened Of, New York 2008, p.1. footnote 8

- ‘Eine Künstlerin aus Afghanistan gestaltet Kirchenfenster.’ MK Online (12th March 2020), available at https://mk-online.de/meldung/eine-kuenstlerin-aus-afghanistan-gestaltet-kirchenfenster.html, accessed 4th June 2020. footnote 9

- J. Elkins: On the Strange Place of Religion in Contemporary Art, Abingdon 2004, p.v. footnote 10