Lakwena Maciver: A green and pleasant land (HA-HA)

by David Trigg

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 20.12.2022

At face value, the title of this exhibition reads as a sardonic response to William Blake’s famous evocation of England in his poem ‘And did those feet in ancient time’. Certainly, it could be considered a comment on the dire state of post-Brexit Britain, or perhaps it alludes to the racism that Lakwena Maciver (b.1986) experienced after returning to Britain from Ethiopia, where she lived for several years as a child. The specific reference is, in fact, to the ha-ha: a concealed walled ditch often found on country estates, which is designed to prevent livestock from entering certain areas while maintaining uninterrupted views of the landscape. Several are present at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield (YSP), which the British-Ugandan artist uses as a metaphor for contemporary power struggles between authoritarian gatekeepers and those upon whom restrictions of thought and expression are increasingly imposed.

Ha-has, which divide up land by creating discreet boundaries, were used by wealthy landowners during the English enclosure movement of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when common land was appropriated and fenced off for private farmland. Of course, the desire to control the land was not confined to these shores: the history of British colonialism is one of theft, expropriation and the subjugation of territory and people around the world. Maciver’s father, for instance, grew up in the Protectorate of Uganda, the modern history of which lies in the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, where the leaders of thirteen European countries and the United States discussed the partitioning of Africa and control of its resources. In her vivid paintings and textile works, Maciver traces a line from these historical events to contemporary society, where the interests of the few continue to be served at the expense of the many.

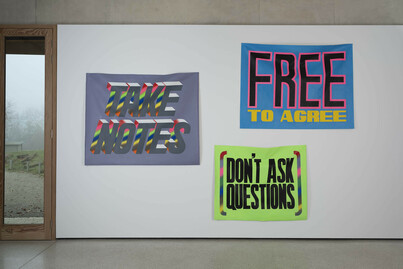

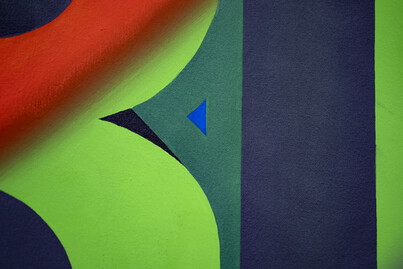

From a distance, the colourful protest banners FIG.1 pinned to the walls of the Weston Gallery at YSP appear to be commercially printed but, on closer inspection, it becomes apparent that they are painstakingly hand-painted FIG.2. Produced with the precision of a sign writer, each one carries a different slogan: ‘FREE TO AGREE’, ‘DON’T ASK QUESTIONS’ and ‘TAKE NOTES’. The statements are patronising and condescending, the kind used by those who want to stifle debate. Another banner, fitted with wooden poles and propped against the wall, bears the ominous multicoloured statement ‘DO BETTER’ FIG.3. Waiting to be picked up and carried on a protest march, its ambiguous message could apply to any number of contexts.

Suspended from the ceiling in the centre of the gallery is a huge COVID-19 face mask emblazoned with the phrase ‘HA-HA’ FIG.4; another billows in the wind in the park outside FIG.5. Titled Cover your mouth (HA-HA) and made from ripstop fabric, these works reframe the mask as a political statement worn on the face. Whereas to many, masks signalled safety during the pandemic, to others they represented a violation of civil liberties. Indeed, while masks became broadly accepted as a method of reducing the transmission of the virus, they were simultaneously criticised as a form of virtue signalling. Maciver’s sculpture capitalises on these tensions, presenting the mask both as a symbol of protection – ripstop fabric being commonly used for tents, sleeping bags and waterproof clothing – and of the muzzling of free speech. One of the work’s most disturbing elements, which is easily missed, is a noose tied from one of the ear cords – a reference perhaps to online ‘lynch mobs’ seeking to cancel dissenting voices.

The term ‘ha-ha’ was supposedly derived from the expression of mild surprise or amusement uttered by a person upon discovering the hidden landscape features. At YSP the emphasis is on laughter of the raucous variety, which fills the gallery by means of a recorded soundtrack of belly laughs, guffaws and howls. Initially raising a smile, it soon starts to grate. At times, the hilarity verges on the maniacal, creating an unsettling atmosphere where laughs sound more like screams of horror. Laughter, it is said, is good for the soul, but what if you are on the receiving end? By juxtaposing this destabilising soundscape with her authoritarian-inflected banners, Maciver challenges us to consider which side we are on.

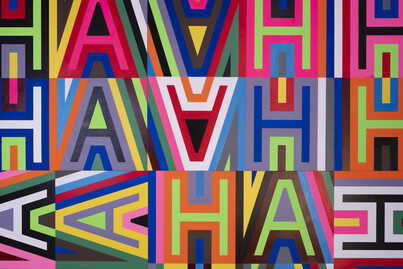

Allusions to laughter continue with a wall of multicoloured paintings, in which the phrase ‘HA-HA’ is repeated fifty-four times FIG.6. Rendered in a graphic style with bold, vivid colours, the capitalised letterforms deliver an optical buzz that recalls Frank Stella’s geometric abstractions and Barbara Kruger’s striking text-based works. Some panels are hung upside down or on their side FIG.7, which serves to emphasise their rigorous divisions of line and colour. Scanning one’s eye over the wall, the phrase slips in and out of focus, hovering between legibility and abstraction, an experience that is similar to semantic satiation, the phenomenon in which a word seems to lose its meaning after prolonged repetition. The piece also recalls Brian Fell’s Ha-Ha Bridge (2006), a permanent outdoor commission at YSP: a steel walkway that straddles a walled ditch and incorporates the same word repeated along its sides. However, whereas Fell’s bridge conveys a light-heartedness, Maciver’s wall is almost uncomfortable in its intensity.

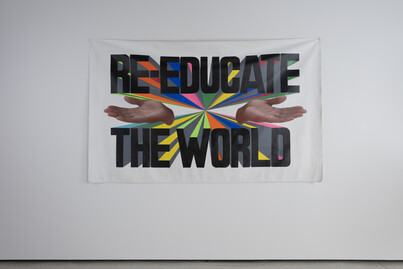

For an artist known for delivering uplifting doses of positivity and optimism, there is a surprisingly dark thread running through this exhibition. The banner Re-Educate the World (HA-HA) FIG.8 is particularly sinister – the titular phrase, spelled out in black capital letters against a rainbow starburst, is accompanied by a pair of open hands suggesting altruism and kindness. However, the notion of re-education conjures up ideas of authoritarian regimes and the colonial impulse to expose indigenous people to a ‘superior’ culture, using education as a guise to mould values and gain social control.1 ‘My father understood very well the ability of those in power to use language to reframe oppression as care [...] to elevate their own beliefs and values and to subjugate and erase those of others’, writes Maciver in the gallery handout. She finds a parallel between such mental enslavement and our contemporary sociopolitical climate, in which political narratives are carefully controlled and the challenging of cultural orthodoxies is increasingly costly.

In what is the artist’s most critical show to date, these works speak pointedly to a polarised culture, in which an increasingly narrow set of ‘politically correct’ values are promoted and the mere articulation of a different point of view is, to some, considered a threat. At the heart of this exhibition is an uncomfortable question: to what extent are opinions and the free expression of ideas becoming colonised in our society? As Maciver writes, ‘are we in danger of simply swapping one orthodoxy for another?’. The 500 acres of fields, hills, woodland, lakes and gardens that form the magnificent backdrop to this exhibition were once a private country estate. Today, this former aristocratic residence is open and accessible to a broad and diverse audience. For Maciver, the fact that those who were once excluded are now welcomed in is an important subcurrent, alluding to the notion of a utopian, paradisiacal place, which is an important leitmotif in her practice. As the artist has said, ‘at its heart, my work is about a longing for paradise’.2 For all its tensions and dissonance, A green and pleasant land (HA-HA) suggests that a place where all voices are heard is not only desirable but essential to human flourishing.

Exhibition details

Lakwena Maciver: A green and pleasant land (HA-HA)

Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield

12th November 2022–19th March 2023

Footnotes

- See Ç.T. Mart: ‘British colonial education policy in Africa’, International Journal of English and Literature 2 (2011), pp.190–94, available at www.academicjournals.org/journal/IJEL/article-full-text-pdf/1E168731407, accessed 15th December 2022. footnote 1

- Lakwena Maciver quoted from D. Trigg: ‘Lakwena Maciver– interview: “I like to think my work will bring hope to people”’, Studio International (28th January 2022), available at www.studiointernational.com/index.php/lakwena-maciver-interview-i-like-to-think-my-work-will-bring-hope-to-people, accessed 28th November 2022. footnote 2