Kaye Donachie: Song for the Last Act

by Beth Williamson

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 15.09.2023

It has been almost sixty years since the critic John Berger (1926–2017) wrote his essay ‘No more portraits’ (1967), in which he argued that portrait painting was no longer viable.1 This was, as his biographer Tom Overton has written, ‘a kind of autopsy for the tradition exemplified by the National Portrait Gallery’.2 However, when Portraits: John Berger on Artists was published in 2015, the critic Jackie Wullschläger described it as a volte-face on Berger’s clarion call issued decades earlier.3 The work of the Glasgow-born painter Kaye Donachie (b.1970) charts a line between these two positions. Rather than exact depictions, she creates composite portraits, the subjects of which appear to be seen through a blurred or distorted vision of reality. She reimagines historical women – often marginalised figures, including avant-garde poets, performers and artists – in images that are simultaneously contemporary and evocative of another time and place. Her cast of modernist muses includes Claude Cahun (1894–1954), Emily Dickinson (1830–86), Nina Hamnett (1890–1956), Emmy Hennings (1885–1948), Mina Loy (1882–1966), Edna St Vincent Millay (1892–1950), Lee Miller (1907–77) and Corinne Michael West (1908–91). As the artist has explained:

I am drawn to the charisma and intensity of these individuals. Their portraits serve to evoke an appeal to a time, place or movement. My preoccupation with the figures I choose to paint is with the assumption that they have a clear sense of their identity. And, as artists and muses, they were able to direct how they chose to represent themselves through art and literature.4

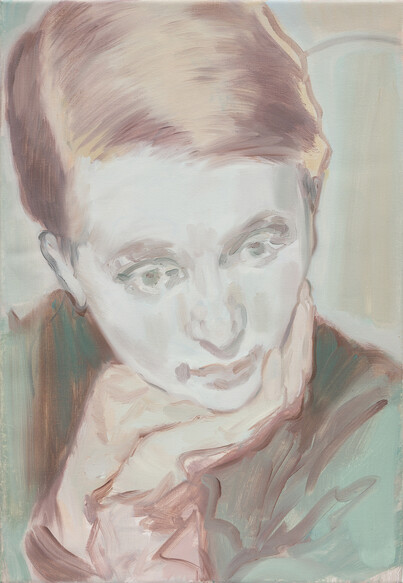

Donachie’s atmospheric portraits are based on black-and-white archival photographs, as well as her own research into each subject’s life and work. Using a distinct colour palette of blue, grey, mulberry and green tones, Donachie’s protagonists emerge out of loose, gestural brushstrokes. Described by the artist as ‘vehicles for painting’, her portraits employ the face as an ‘armature’: a familiar structure on which figural and abstract gestures can be projected and read simultaneously.5 In On Photography (1977) Susan Sontag defined photography as a ‘way of imprisoning reality […] of making it stand still’.6 Donachie, however, ‘redeem[s] images from the past and morph[s] them into a single moment of time’ (p.17).7 Through the translation of specific photographic source material to abstracted, composite portraits, she rescues her ‘characters’ from their static, imprisoned reality.

In 2020 Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, purchased Donachie’s painting Monotonous Remorse (2019), which acts as a starting point for the present exhibition as well as an accompanying display of works selected by Donachie from the gallery’s collection. Here, the artist has juxtaposed paintings, drawings and prints by well-known and overlooked artists: two etchings by Édouard Manet – one of which (1867) is based on his painting Olympia (1863; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) – sit alongside drawings by Eileen Agar (1899–1991) and a collage by Pauline Boty (1938–66). Despite spanning over one hundred years, the works share a fleeting, ethereal quality: of subjects committed to canvas or paper by the barest of means. Manifesting as a sort of ‘chorus’, the display poses narratives that dissolve into one another ‘in [the] manner of an elliptical poem or conversation through time’.8 Donachie’s selection evidences her interest in the interface between the real and the imaginary and figuration and abstraction. The display is set against a wallpaper designed by the artist, which further frames the gallery as a theatrical set for her cast of players.

The exhibition title, Song for the Last Act, is taken from a poem of the same name by Louise Bogan (1897–1970), which begins ‘Now that I have your face by heart, I look / Less as its features than its darkening frame’. The poem’s theatrical allusions and its references to reflection and recollection, in particular the notion of ‘having’ one’s face ‘by heart’, are pertinent to Donachie’s creative process, in which she operates on a form of representation that is far from exact. The exhibition comprises a small selection of new and recent paintings, including four created specifically for the exhibition. A sense of distance ensues from the non-specificity of Donachie’s subjects and the blurring of features. Frequently, women are presented with downcast eyes, as in Young moon (2018), or shown gazing into the distance, as in Descending into the midst (2022). By combining a muted palette with extremes of light and dark, Donachie drains these faces of colour, while emphasising features and lending a melancholic air to their countenance. This is especially evident in Be lost forever FIG.1 or Silence into weary ears (2018), in which the women’s pallid complexions are in stark contrast to their heavy hollowed out eyes and the dark shadows shown around their nose and lips.

Donachie’s paintings occupy an ambivalent space between figuration and abstraction. In some, such as In the depths FIG.2, faces are rendered with distinct characteristics, for example the crisp curve of a chin, which rests heavily on a more nebulously defined hand. In other instances, such as Dark renewing FIG.3, bodily boundaries dissolve and features blur into one other, extending the artist’s mode of abstraction and setting the figure at a further remove from the viewer. In three recent works – Notes shift (2023), To echo FIG.4 and Like walls the mirrors stand (2023) – the relationship between figure and surroundings changes again, as the distinction between architecture, foliage, clothing and body is eroded even further. In To echo a face fills the entire canvas, both emerging from and dwarfing a veil of vegetation. The layering of two seemingly unconnected image registers recalls the fade or transition between scenes in cinema, which lends the work a narrative quality, eluding to what cannot be seen beyond the frame.

Two works in the exhibition depict not a figure, but a single slender hand. In Come now, be content (2016) it stretches out, seemingly to hold a drooping flower head, whereas in the cyanotype Untitled VIII FIG.5 it reaches across an artist’s palette, which is superimposed over a landscape so that the thumb hole stands in as a celestial body. These paintings come to exist as manifestations of Donachie’s process: the many different realities that she has researched and distilled into single images. The layering in Untitled VIII presents two distinct realities that coexist, whereas the hand in Come now, be content appears to materialise out of thin air. In both images the viewer is reminded of Donachie’s departure from direct, concrete representation: ‘there is no point in creating a reality because there is none’.9 The fluid and mutable qualities of Donachie’s paintings parallel the ambiguous, shifting nature of identity and the external world. Unsettling, perhaps, but equally reassuring in the myriad possibilities they open up. Set apart from the tradition of portrait painting, these works speak to Berger’s understanding of the genre, in which ‘every mode of individuality now relates to the whole world’.10

Exhibition details

Footnotes

- J. Berger: ‘No more portraits’ [1967], in idem: Landscapes: John Berger on Art, London 2016, pp.164–70. footnote 1

- T. Overton: ‘Introduction: The company of the past’, in J. Berger: Portraits: John Berger on Artists, London 2015, p.xviii. footnote 2

- J. Wullschläger: review of John Berger: Portraits: John Berger on Artists, London and New York 2015, in The Financial Times (25th September 2015), available at www.ft.com/content/76a0f4f8-6068-11e5-9846-de406ccb37f2, accessed 15th September 2023. footnote 3

- Kaye Donachie, quoted from ‘Artist interviewed’, Pallant House Gallery Magazine 57 (summer 2023), pp.36–39, at p.37. footnote 4

- Kaye Donachie, quoted from J. Sofronijevic: ‘Kaye Donachie’s ‘nuanced personal choreography’, gowithYamo.com (5th June 2023), available at www.gowithyamo.com/blog/artist-interview-kaye-donachies-nuanced-personal-choreography, accessed 15th September 2023. footnote 5

- S. Sontag: On Photography, London 2008, p.163. footnote 6

- Catalogue: Kaye Donachie: Song for the Last Act. By Simon Martin and Kaye Donachie. 86 pp. incl. 40 col. ills. (Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, 2023), £14.95. ISBN 978–1–869827–72–4. footnote 7

- Donachie, op. cit. (note 4), p.39. footnote 8

- Donachie, op. cit. (note 5), p.30. footnote 9

- Berger, op. cit. (note 1), p.170. footnote 10