Emma Hart: Banger

by Susannah Thompson

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 26.11.2018

As a visitor to the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, there is sometimes a sense that you know what you’re going to get – not least, as a lecturer in a Scottish art school, a hundred undergraduate essays on the latest show. Over the last decade or so, the Fruitmarket’s offerings have tended towards a combination of one or more of: Scottish artists who were big in the 1990s; an art-historical thesis-as-exhibition; scaled-up neo-formalist sculpture; or the latest curatorial trend, slightly after the fact. While this perception is perhaps unfair (take, for example, the recent outstanding exhibitions of work by Lee Lozano, William Kentridge and Vivienne Koorland) it is nevertheless true to say that visitors are rarely surprised by what they encounter.

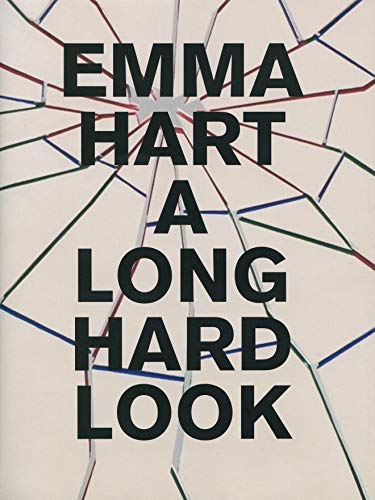

It may well be that it is the gallery’s dated corporate branding that gives off the whiff of an inflexible house-style, or something to do with the standard café-bookshop-education room configuration of the place. The latest show, however, is a hard one to call. It fits with what we might expect of the gallery’s taste – bold, colourful, installation work that (from a distance) veers towards what Alex Coles and others have deemed ‘Design Art’ in its aesthetic,1 but the themes and ideas explored are more expansive, less easy to categorise. Here, the London-based artist Emma Hart presents two discrete exhibitions: Mamma Mia! (2017) on the ground floor and a group of new sculptures collectively titled Banger (2018) directly above, on the first floor. Mamma Mia!, shown at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, last year, is the result of Hart’s residency in Italy in 2016, awarded as part of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women for which Fiona Bradley, the Director of Fruitmarket, was one of the judges.

Ceramics take centre-stage across both bodies of work. In Mamma Mia! they take the form of a group of eleven large sculptural ‘lamps’ FIG.1. These objects could also be read as heads or helmets, with noses and rounded skulls. The ‘heads’ are illuminated from inside and cast shadows in the shape of speech bubbles on the gallery floor, adding to the personification these glamorous, absurdist objects. Equally, they could be upended measuring jugs, with spouts and fill lines. Whatever they are, ten are suspended from the ceiling, one lies on the gallery floor and all are connected by red electrical cables, which zigzag like the lines on a heart monitor as they snake across the wall. Interspersed among the lamps are ceiling fans in the shape of oversized cutlery, whirring ominously just above head height. Standing directly beneath the ‘heads’ we can look up to see their hollow interiors FIG.2. From this vantage point, the glossy monochrome exteriors give way to saturated colour (bright red, yellow, blue, green) and pattern (abstracted tears, fingers, eyelids).

As a whole, the works allude to conversation, to domestic disputes and family dinners. And while tonally there is something of the witty Italian postmodern design of Ettore Sottsass and his Memphis peers, the finish is resolutely less slick, more obviously handmade, beautiful but a little clunky. During Hart’s residency in Italy, her research for what would become this body of work included time spent at a psychotherapy school in Milan specialising in family therapy, a period in Rome looking at funerary sculpture and a further period studying ceramic techniques in Faenza, during which Hart focused specifically on learning the technical skills required to make faience, the tin-glazed earthenware pottery historically produced in the city. Mamma Mia! gathers together these experiences and themes in the manner of expanded object theatre. What at first glance around the gallery entrance looks like yet another heart-sinking sculptural nod to Modernist design or one more brash, neo-formal installation, has, on closer inspection, far more substance, a welcome sense of humour and much more heart.

In the companion show, Banger, Hart extends her interest in producing large-scale, sculptural ceramics, a material with serious currency in contemporary art – take, for example, Phaidon’s book Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art (2017), Phil Root’s and Giles Round’s Grantchester Pottery, Aaron Angell’s Troy Town Art Pottery and countless other examples including Hart’s recent work with Jonathan Baldock in the Love Life (2016–17) exhibitions.2 While ceramics departments continue to close and kilns are in short supply in UK art schools, interest among artists in these materials has seen a huge resurgence over the last decade or so. Hart has worked across sculpture, photography, film and installation, but she has said that she turned to ceramics as a way to find ‘the real’ in art, seeing clay as ‘an exciting way to talk about chaos’. Both exhibitions force the audience to physically negotiate and navigate the works. As in Mamma Mia!, visual puns abound in Banger and the effect can be both playful and disorientating. Headlights in a rear-view mirror face you as you ascend the stairs, two of the four double-sided car windscreen sculptures flank the entrance and exit of the space, forcing you to walk around them, while a crash barrier titled Gatecrasher similarly seems to block the way FIG.3.

Many of the titles here – Slippery Sloped FIG.4, Wipe Out, Dark Past, Totalled – imply violence, danger and loss of control. But up close, the pattern and decoration of the tiles (windscreens) is exquisite FIG.5, offering real visual pleasure through a gorgeous, decorative fusion of colour and form comparable to geometric Art Deco or Suprematist textiles FIG.6. While the beauty of these objects may seem at odds with their ostensible, low-fi subject-matter, it is worth remembering that car culture, too, is obsessed with surface and pattern, with modification and ‘pimping rides’. Bangers, after all, have hand-painted exteriors, sports steering wheels, reupholstered seats, vinyl decoration. At the same time, they are perilously close to threadbare tyres and tied-on exhausts, to danger, obsolescence and being ‘clapped out’. In this, Banger could be seen as an extension or development of Hart’s earlier show Car Crash at Gallery Lejeune, London, in 2016. While less overtly about collision, in both Banger and Mamma Mia! situations are reversed, bodies are part-machine and insides become outsides. The works could be giant props, waiting to be moved, reconfigured or activated.

Exhibition details

Footnotes

- A. Coles: DesignArt, London 2005. footnote 1

- Love Life: Jonathan Balddock and Emma Hart was on view in three parts: PEER, London (9th November 2016 – 28 January 2017); Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool (17th June – 12th August 2017); and De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-On-Sea (21st October – December 2017). footnote 2