Elliott Hundley

by Jareh Das

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 21.06.2019

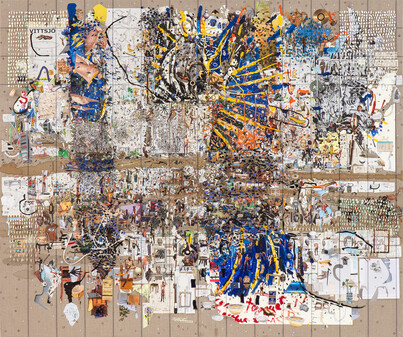

The Los Angeles-based artist Elliott Hundley has long embraced chance, accident and improvisation in his paintings and sculptures, bringing together techniques of collage, assemblage, and autobiographical photomontage, often incorporating images of friends and family. His large-scale works, particularly his paintings, are a visual assault on the eyes, as ‘cut up images, found objects, urban detritus, and other materials’ are pinned directly onto the canvas to create remarkable constellations of images that reveal new details each time they are encountered FIG.1. Hundley selects his material from a warehouse studio filled with a vast archive of magazine clippings, photographs, found objects and furniture. He continually finds ways of using and reinterpreting this personal archive to make new meanings.

Literature has grounded the narrative of many of his previous works, which have culled characters from texts including Euripides’ Hecuba and Antonin Artaud’s The Plague. In his current exhibition, Clearing,at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Hundley takes a slight departure from his usual approach. The body of work created during the past year comprises five new paintings – in which he incorporates automatic drawing – with accompanying sculptures mounted on benches and finished in bronze.

Meanwhile, at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, Hundley makes his curatorial debut with the display Open House: Elliott Hundley, the first in a new series of exhibitions curated by Los Angeles-based artists. Here, he brings together works of art by over thirty artists across a variety of media including film, sculpture, painting and installation to explore the diverse ways collage operates. ‘I have lived downtown and close to MOCA for fourteen years and its one of the few museums in town which serves as a library’, Hundley explains, ‘I got asked by the curator Bryan Barcena (MOCA Assistant Curator and co-curator of Open House) to take part in this and I loved the idea of using the museum’s collection as a resource to learn, similar to how I use literature in my work’. He is also clear that rather than a focus on methodologies of collage, his selection reflects the ways artists have introduced strategies employed by collage across different media including printmaking, photomontage, film, sculpture and painting.

The first work encountered upon entering the exhibition is One White Paint Brush and a Pony Tail (1989) by Noah Purifoy. Probably the most famous collage/assemblage artist in the region and famed for his lifelong project, the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum in Joshua Tree. Purifoy sets the tone for considering the historic importance of collage and assemblage and its development on the West Coast. This vivid large-scale work is characteristic of his charred wood and melted-metal assemblages. Nearby, Betye Saar’s The Destiny of Latitude & Longitude (2010), a birdcage filled with silver hairs and model slave ships, provides a deeply moving reflection on the Middle Passage. Sharing the space with Purifoy and Saar, Rachel Harrison’s I'm No Monkey (2005) FIG.2 probes notions of high art, kitsch and consumerist culture with her carefully crafted assemblage of everyday objects including wood, polystyrene, cement, acrylic, encaustic, plastic skulls, wig and a tiara, an assortment laden with pop-culture references.

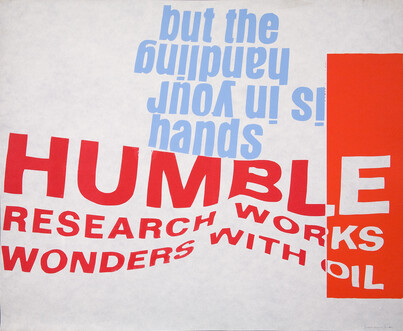

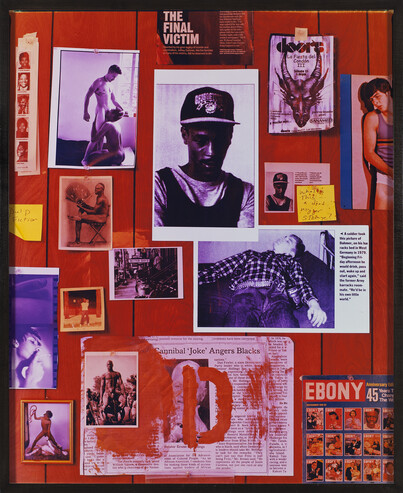

In the adjacent gallery space, three serigraphy works by the artist, educator, nun and social activist Corita Kent (also known as Sister Mary Corita) further explore the theme of collage in an expanded form FIG.3. Kent made these distorted typographic works by photographing advertisements and then wrinkling, ripping, cropping and re-photographing her photographic prints, a process she described as ‘a “finder”, a “looking tool” that “helps take things out of context”’.1This repetition is also explored in the layering of imagery employed by Lyle Ashton Harris for The Watering Hole II and The Watering Hole VIII FIG.4 (both 1996), which, according to the artist, draw on ‘the metaphor of the watering hole as a place of rejuvenation and as well as a site of violence’. These works are part of a series of nine red-hued photomontages, collaged and then re-flattened via the lens of the camera, that are based on the infamous killings of seventeen Black, Latinx and Asian men and boys killed by Jeffrey Dahmer. Harris’s material includes newspaper clippings related to the crimes, his own personal photographs, Post-it notes scribbled with text, including quotes from Pulp Fiction (1994), album covers, images of sex, printed film stills, a postcard reproduction of a Basquiat painting, the American flag and advertisements for all-male spas. Harris’s work comments on both Dahmer’s cannibalism and wider society’s unending need to consume information, and how, according to the artist ‘we all are implicated in that notion of the consumption of the other’.2

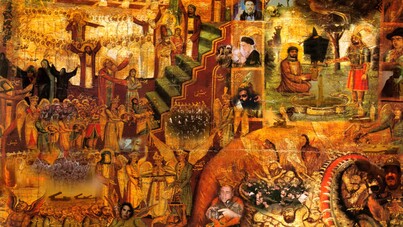

Conversely, Noah Davis’s painting All Those Lost to Oh Well (2010) FIG.5 and Brenna Youngblood’s 3 dollar bill (dirty money) are deft examples of how collage can be used in abstraction, through a process of adding, erasing and layering. Hundley includes an early work, Hyacinth (2006), a stunningly detailed painting based on representation of cycles of decay and renewal in Greek mythology that incorporates paper, photographs, plastic, corkboard, wood, string, found objects, feathers, silk, charcoal, pastel, oil stick, cardboard, fabric, wire and ribbon that seemingly spills out of its frame and onto the walls and floor of the gallery.A standout piece in the exhibition is Shoja Azari’s Coffee House Painting FIG.6, a film projected onto a mural-size printed reproduction of Iranian painter Mohammad Modabber’s well-known The Day of the Last Judgment (1897). Paintings of this style are commonplace as backdrops in Iranian tea and coffeehouses that depict tales by travelling storytellers based on traditional Shiite myths and legends. Azari animates the mural with video clips taken from the internet, making sections of the picture come alive with unsettling scenes including the Iraq war, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the Iranian Revolution.

With Open House, Hundley presents collage in an expanded field, charting its use across different generations of artists who explore a range of subjects through its wide processual possibilities. It is collage’s potential for experimentation and spontaneity across media that reinforces its importance to both historical and contemporary art.

Exhibition details

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA)

14th April–16th September 2019

Footnotes

- See collection record for Ha, by Sister Corita Kent (1966), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, available at https://whitney.org/collection/works/29776, accessed 14th June 2019. footnote 1

- M. Durón: ‘Out side in: In his arresting work, Lyle Ashton Harris looks to the recent past for new ways forward’, Artnews, available at http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/02/lyle-ashton-harris/, accessed 14th June 2019. footnote 2