Carol Rhodes was born in Edinburgh, spent her childhood in India, and has lived and worked in Glasgow since the late 1970s. Her paintings are representational. They are exclusively landscapes and modest in scale, her handling of the medium controlled but not without its flourishes. So, we might think of her as a Scottish painter, of the same family tree as, say, S.J. Peploe, a tree which has its roots in France. That, however, is about as far as any historic Scottish connection goes, for Glasgow has become, in recent decades, one of the centres of art in Europe, and in this Rhodes has played a part as both artist and activist.

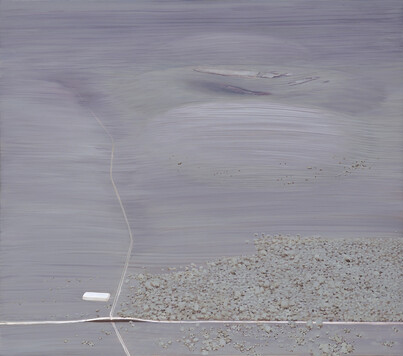

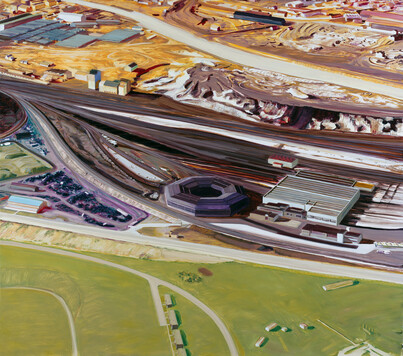

A characteristic of Rhodes’s paintings over the past twenty-five years is their aerial perspective, which air travel has made familiar but it is unusual in landscape painting (although one thinks of Peter Lanyon in his glider), where the effect is to eliminate the recessive view, with everything ending up on the picture plane. More specifically there is a distance between ground and viewpoint that Rhodes works with, between the detail of the close-up and the abstraction of distance. This might be the point at which detail begins to blur, where the precision of photography can be replaced by the ‘smear’ of the paintbrush. This zone has considerable range and allows degrees of abstraction, between paintings of distance and synthesis such as Hill and Trees [fig.1] and the bold detail of Industrial Belt [fig.2]. At the abstract end of the register especially there are marvellous invented or constructed compositions.

The subjects are recognisably of our time: airports, seaside towns, industrial zones and places where the edges of cities meet the land, none of which has been depicted quite like this before, although the high perspective and even the handling reminds me of William Nicholson’s paintings, his aerial view of the Malaga bull ring, for example. (An echo of the bull ring can be found in Rhodes’s anonymous hexagonal buildings, although here they are closed in, institutional). This landscape, as Moira Jeffrey points out in her introduction to this attractive and welcome monograph, is the periphery of the globalised world, periphery as the edge of capitalism. Much is made in both essays (the other is by the art historian, curator and champion of artists Lynda Morris) of the associations that these landscapes might evoke, the history and the grim future that is embedded in them.

This is surely valid but does not prevent us relishing their painterly qualities. Morris quotes Rhodes as saying that the surface quality of the paint is ‘almost pathologically important to her’. And the paintings are full of light, that special light of her country, Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘gray country, with its rainy, sea-beat archipelago’. Drawings (a number are reproduced in the book) allow some insights into the way the paintings are made. In the interview between the artist and Andrew Mummery in the book, Rhodes explains that the drawings ‘are cartoons for paintings [. . .] I work out through them how to put together things from different photographic sources [. . .] The lines of the finished drawing are then traced onto the primed board’. Those photographic sources come from books of aerial photography, geography and geology, although some may have been taken by the artist – the chronology includes a riveting photograph of Rhodes, with helmet and camera in hand, in front of an orange helicopter.

Rhodes has found time and energy to curate the works of other painters. In 2012 she and her painter partner Merlin James arranged and installed an exhibition of the work of Clive Hodgson. The exhibition was held in their home, an early nineteenth-century terraced building, which also houses their studios. Hodgson’s paintings had never looked as good, never been as well installed, never been as well lit. The building is splendid, of a period and style one associates with Edinburgh rather than Glasgow, and very centrally located, on the banks of the Clyde opposite St Enoch Station. Rhodes is indeed a Glasgow artist. And she has made a signal contribution to the culture of that city (in which this reviewer grew up and left at the first opportunity).

Carol Rhodes is painting after conceptualism. The book’s two authors reveal meanings as layered as the paintings themselves, referencing, for example, the metaphor of the caravan in Patrick Keiller's films with an early Rhodes painting, and associating Rhodes's interest in the edges of landscape with her holding hands around the perimeter fence at Greenham Common. But they are also full of the visceral pleasures of painting: the sweep of the brush across a broad area, the way the paint turns around a building or a road, describing and creating the image. Whether by intention or manipulation the details are a delight – look for example at those tight curves in Airport [fig.3] – what a delicate tracery of roads and open spaces, like the windows of a Gothic cathedral; or the circles and half-circles of the formal gardens in Seafront [fig.4], which sit so oddly beside that strange purple-red colour Rhodes has used for the land.

There have not been many opportunities for us Sassenachs to see Carol Rhodes’s work in recent years (since her dealer Andrew Mummery closed his London gallery in 2014). The present volume, with its handsome illustrations, excellent details (close enough to see both incident and ‘facture’) and appropriately landscape format, is some compensation.