Candice Lin: The Animal Husband

by Helena Vilalta

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 24.05.2024

Upon entering The Animal Husband by Candice Lin (b.1979) at Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh, the visitor is greeted by a totemic, cavernous, animal-hybrid creature made of glazed ceramic FIG.1. With cat’s paws and human ears, its long, conical head is riddled with ovoid openings in the shape of wolf skulls. As one moves closer, one becomes aware of a scent emanating from its body. The ammonia smell – wolf urine, the wall label states – is pungent but not entirely repellent. The viewer has to bend down in order to fully take it in. Perhaps this is exactly where Lin wants us: crouching down, sniffing around, our body language approximating that of the two cats whose narratives take centre stage in this exhibition.

Building on Lin’s long-standing interest in more-than-human worlds, The Animal Husband prods at normative constructions of animal-human intimacy. Suspended in the rectangular gallery is a large rotating screen, on which two short video animations alternate. Each is narrated from the perspective of a cat who has co-habited with Lin: The Blueness FIG.2 gives an account of the final days of White-n-Gray, a feral cat who frequented Lin’s porch in Los Angeles for many years; and The Animal Husband FIG.3, in which Lin’s pet cat Roger reflects on his own domestication. Although they strike slightly different tones, the two videos lure the viewer into a fantastical cat-world, which is inflected with dry humour and elements of science fiction. Combining hand-drawn and digital animation, The Blueness is akin to a film noir told from the point of view of a dead narrator. White-n-Gray is cast as a bon vivant, and our guide to a suburban underworld where felines must distinguish coyote predators from their robot look-alikes hunting for data instead of food. Before being eaten up by a Worm God, White-n-Gray introduces us to his nephew, a black-and-white cat – ‘always in a tuxedo, the gender-queer one’ – who likes to roam the porch despite having the whole house to himself: Roger.

This threshold between inside and outside – the house, but also the body – is central to The Animal Husband, in which Roger considers the negotiation of corporeal and domestic boundaries in his relationship with Lin. The cadence of the human call that lures Roger indoors acts as a refrain throughout the video: at once a reminder of the tacit contract that binds pets and humans, and an invitation to tease it apart. The video is told, in part, as a duet, interspersing Roger’s and Lin’s accounts of their domestic intimacy. Whereas Lin tends to couch their displays of affection in the script of sublimated love, Roger has trouble distinguishing all the petting, rubbing, touching and loving from the forms of sexual interaction with animals that are proscribed by human morality and law. ‘Flesh lumps’ – meaning humans – ‘are obsessed with genital nerves’, he tells us:

But flesh lumps want to take these bundles of nerves, these sensitive spots, and cut them off or control them. They want to say: you cannot rub this here or there, insert this here or there. There are so many rules about who can rub and how can rub and when to rub and for what end. And yet she rubs me every day and every night. Pleasure flowing through us, like a ribbon wrapping us in a Christmas bow.

Much like the ape narrator in Franz Kafka’s ‘A report to an academy’ (1917), Roger’s perspective as a learned animal throws the spotlight on the contradictory ways in which humans regulate social boundaries with other animals, particularly when it comes to sexuality. As told by Roger, the story of Thomas Granger, a young farmer who was hanged in seventeenth-century New England for having sexual intercourse with his farm animals, functions as an exemplary tale of what Amia Srinivasan has identified as ‘the overlap between bestiality and husbandry, and our uneven response to these practices’. In other words, it speaks to the ways in which the moral propriety of human–animal relations are shaped by profit. As she puts it: ‘it’s fine to violate an animal in order to produce milk or meat, but not OK it if turns you on’.1

Hanging near the projection screen, a small pewter pendant attached to a human collar FIG.4 extends Roger’s probe into this moral morass. While the collar recalls BDSM practices and various fetishes, the etching on the back of the pendant suggests that animals too can be made to play the role of submissive humans. A flesh-like skein made of lard and encaustic wax is incised with a drawing of a fluffy lamb; two hands attend to an actual perforation in the wax membrane, which doubles as an opening or wound in the animal’s skin. The word ‘GROOM’ testifies to the linguistic slippage that can occur between animals and children, as it has evolved from denoting the protective care of horses to the harmful manipulation of children for sexual abuse. According to Lin, this series of pendants was inspired in part by bawdy badges worn by pilgrims in the medieval period to scare off the devil, which navigated a fine line between the pious and the obscene. Although there was a humorous side to these medieval badges – or so it appears to our contemporary eyes – Lin’s pendant provocatively ventures into the darkest corners of human desire.

Roger’s report on his life as the titular ‘animal husband’ would be incomplete without an account of castration. Although ‘going into the house’ may have seemed a worthwhile trade-off in exchange for food, affection, comfort and pleasure, Roger tells us that it meant tubes and probes ‘going into his body’. The Animal Husband closes with the cat’s delirious account of his neutering, as he imagines his ‘ball juice’ being sucked from his body and travelling through tubes into the centre of the Earth, where it feeds a strange machine producing cute cat memes for the viewing pleasure of a chuckling rat. This finale is more serious than it might seem. ‘Cuteness’, Sianne Ngai has argued, ‘is a way of aestheticizing powerlessness. It hinges on a sentimental attitude toward the diminutive and/or weak [that is] deeply associated with the infantile, the feminine, and the unthreatening’.2 Sterilisation and the endless reproduction of cat memes turn out to be different sides of the complex process of domestication that Lin’s animation explores: a process, which, as the title suggests, is hard to disentangle from patriarchal constructions of domesticity.

As though to offset the powerlessness of pets in conventional representations of human–animal companionship, a handful of kites suspended at the back of the gallery appear to be plotting a feline counterattack. Compositely titled Feline Messages to the Human World FIG.5, the kites feature drawings of Roger and other cats alongside slogans such as ‘castration is still possible’.3 Rather than a violation of bodily boundaries or a form of emasculation, here castration is imagined as a liberatory possibility: the ‘third sex of cats’ created by domestication is framed as a harbinger of a queer future.4 At the centre of each kite is a circular incision, a form that is mirrored in a diagram painted on the back wall of the gallery. The pattern resembles the visual traces of a rotating propeller, but it is in fact a historical trace: Cicatrix FIG.6 repurposes a nineteenth-century medical drawing of the site of castration, which was published in a missionary treatise on eunuchs in Chinese imperial courts. As well as the representation of a bodily scar, then, it offers different understandings of castration: colonial narratives of the practice as ‘a lack’, on the one hand, and as a cultural tradition endowing eunuchs with greater political agency, on the other. In a recent conversation with the artist P. Staff, Lin noted:

I was really interested in [Howard] Chiang’s description of the nuances of how the eunuch had value and wielded power, sometimes running entire palace courts behind the scenes, where the emperor or empress was just a puppet. So similarly I was thinking about how, like the eunuch who traded in their potential reproductive threat to the royal gene pool, Roger traded in his reproductive threat to the human species, and gave in to the human desire to show dominance through controlling the populations of other species (not to say other races within our own species!). What, if anything, did he gain through this trade? But I don’t know… maybe all this theorising is a way to feel less bad for what I did to him – like trying to believe that maybe Roger deliberately chose to come in and barter his balls.5

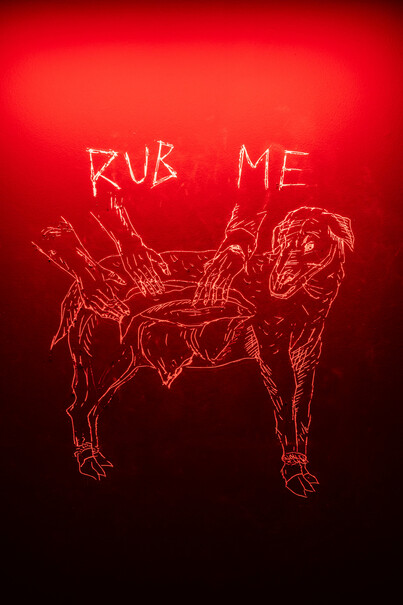

The circular shape of Cicatrix is echoed again in Time Clock (Temple) FIG.7. Inscribed on the object’s round face are detailed drawings of animals historically exploited for profit, such as cochineal and silkworms, which Lin has also incorporated in previous projects. While the works on display in this exhibition continue her long-standing interest in interspecies relations, they also explore a territory that is physically and emotionally closer to home. This vulnerability is particularly evident in the upper balcony, where Lin has etched a series of drawings directly into the black-painted walls. Steeped in red light, they strike a sombre, melancholic chord, their emotions as raw as their material support. With its paws tied up, a lamb cocks its head to look at the open wound on its side. The encroaching human hands could be responding to the animal’s call: ‘RUB ME’ FIG.8. Or are they yanking the lamb’s insides out?

Another etching depicts two prostrate figures embracing. As their faces merge into one, human and animal features also meld into each other. The word ‘BELOVED’ infuses this tender embrace with the anticipation of tragedy. By way of Toni Morrison, it evokes a form of love that is haunted by violence, where kinship is threatened – or indeed shaped – by relations of mastery and property. Life and death, loving and mourning, caring and wounding, are painfully close in these drawings. Read in sequence, they compose an elegiac poem where desire is laced with loss: ‘OH MY FLESH LUMP / RUB ME / MY NERVES / MY DATA / BELOVED / I’M YOURS / SUCK MY / BALL JUICE / LIFE / BECOMING / A ROCK STONE / AGAIN’.

Exhibition details

Candice Lin: The Animal Husband

Talbot Rice Gallery, University of Edinburgh

16th March–1st June 2024

Footnotes

- A. Srinivasan: ‘What does fluffy think?’, The London Review of Books 43, no.19 (7th October 2021), available at www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n19/amia-srinivasan/what-does-fluffy-think, accessed 20th May 2024. The Animal Husband is informed by scholarship in this area, especially G. Rosenberg: ‘How meat changed sex: the law of interspecies intimacy after industrial reproduction’, GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 23, no.4 (2017), pp.473–507. footnote 1

- Sianne Ngai, quoted from A. Jasper: ‘Our aesthetic categories: an interview with Sianne Ngai’, Cabinet 43 (autumn 2011), available at www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/43/jasper_ngai.php, accessed 20th May 2024. footnote 2

- The kites are made in collaboration with artist and kite maker Yaeun Stevie Choi. footnote 3

- Candice Lin, quoted from ‘Candice Lin and P. Staff on their Cats and Castration’, Frieze (10th October 2023), available at www.frieze.com/article/candice-lin-getty-london-2023, accessed 20th May 2024. footnote 4

- Ibid; see also H. Chiang: After Eunuchs: Science, Medicine, and the Transformation of Sex in Modern China, New York 2020. footnote 5

', 2023 installation view courtesy talbot rice gallery university of edinburgh photo sally jubb.jpg)