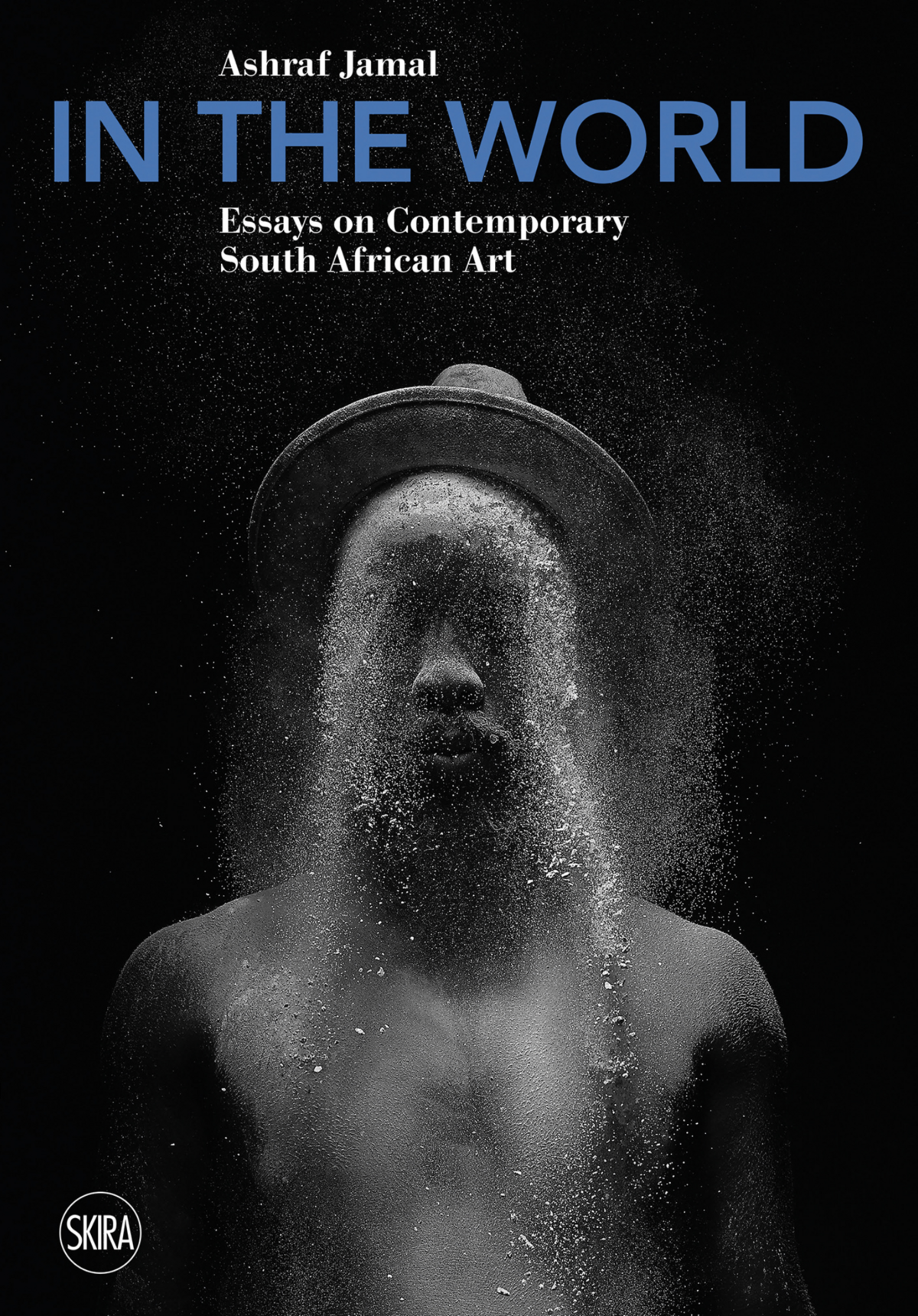

‘There are three rules for writing biography’, Somerset Maugham once quipped, ‘but fortunately no one knows what they are’.1 It is precisely this sort of indeterminacy and irreverence that makes Ashraf Jamal’s writing so compelling. This collection of essays on twenty-four contemporary South African artists is unlike any publication on the topic. Exploratory in tone and sprawling in scope, it considers visual arts in light of the culture wars over identity politics today, and theorises the recent boom of ‘African art’ in terms of a global fetish for a universal language. This provocative analysis stands in stark contrast to the prescriptive and authoritative catalogues and surveys that comprise the majority of literature on the subject. Jamal’s choice of artists is not a canonical one. He mingles revered figures with outliers and students; he considers work in every medium, across generational, social and racial lines. The texts are never generalist, neither stuffed with personal backstories nor flattened into surface overviews. The references are transcultural and omnivorous, from Dickens, Nietzsche and Achille Mbembe to self-help books, Taylor Swift and bathroom graffiti. Jamal’s detailed, passionate essays on art and exhibitions encountered in the last two years are, in verve and insight, a masterclass in art criticism. It may be no revelation that South Africa is a cultural powerhouse, but this uniquely thought-provoking contribution to its scholarship crowns Jamal as one of the country’s leading intellectual firebrands.

Always in erudite conversation with Western critical theory, Jamal discusses art in South Africa in relation to what he perceives as the capital woes of our time: the ‘spectre of absolutism’, nihilism and a ‘dangerously exclusionary identity politics’ (p.13). In line with Pankaj Mishra’s diagnosis of a global pandemic of anger,2 Jamal spins his own dystopian view. Ours is a ‘catastrophically appalling time’ (p.12), he claims. The betrayed promises of racial justice, compounded by an unprecedented socio-economic crisis, have fuelled a political climate in South Africa that is described as the ‘killing fields of Right and Wrong, Good and Evil, the blood-soaked hell of Absolutism – the fascist dawn of the Alt-Black’ (p.23) and a form of ‘“neo-black” colonialism’ (p.53). The mass student protests that have broken out across university campuses, with their demands to decolonise the culture, are summarily dismissed as ‘a devolution, a bloodying of mind, an excremental auto-da-fé, an inconsolable mounting of pain upon pain, an Everest of Suffering’ (p.22). Such heavy-handed condemnations smack of apocalyptic alarmism. Yet this hyperbolically bleak view is counterbalanced by an equally atypical belief in the restorative powers of art. The essays are then driven by compassion and empathy, as critical tasks facing a nation that ‘must find the way to reconcile its abiding suffering through a redemptive future’ (p. 215). Art, for Jamal, is part and parcel of Steve Biko’s prophecy that, in the wake of imperial domination, industrial revolution and military hostility, ‘the great gift still has to come from Africa – giving the world a more human face’.3 This forward-thinking, generative quality makes for fresh writing, especially in the context of a South African art discourse still firmly in the grip of the twin compulsions to document and protest.

Loathe to snap judgments and quick fixes, Jamal takes his time with the works, and is drawn to their quirks and nuances as well as their resistance to overarching interpretations. This way of engaging with art aims not to stave off or think away, but to embrace the contradictions and complexities of inhabiting the world. The tiniest detail – a green hue in a painting by Kate Gottgens FIG.1, the eyes in one of Santu Mofokeng’s photographs FIG.2, a hand in an installation by Simphiwe Ndzube FIG.3 – sparks unexpected existential illuminations and unlikely intellectual associations, although unfortunately without footnotes. This evocative method pulls the viewer into an intimate relationship with these works, a form of affective immersion that is ultimately about interdependency and connectedness.

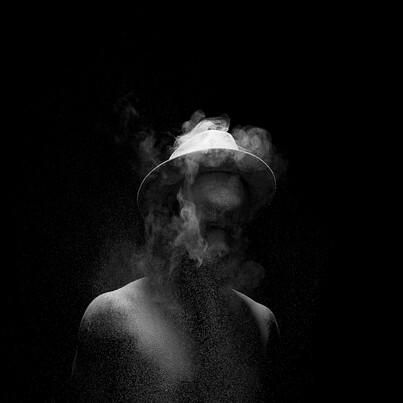

That so few arts and humanities scholars are cited stems partly, one suspects, from a certain animus towards how universities handle gender and race. Jamal repeatedly blasts the ‘essentialist and divisive circuitry of identity politics’, the ‘obsessive-compulsive desire to fix blackness’ (p.188) and ‘identitarian tyranny’ (p.389). They all replicate, Jamal argues, a polarised view of humanity that explains art away by racial affiliation. His essays on Pieter Hugo FIG.4, Zanele Muholi or Mohau Modisakeng FIG.5 excel at the opposite. These are prolonged and empathetic engagements with the works, reframing conventional readings by refusing rigidified categories of whiteness and blackness, and authorising new ways of thinking about them. This echoes Paul Gilroy’s overlooked plea for a planetary humanism, an ethics that is wary of using race to undo race.4 Jamal places aesthetics at the heart of that project. At one point, he cites J.M. Coetzee who, in turn, took the line from Kafka: ‘A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us’. It sets the tone for this rousing account of twenty-first century art. Jamal’s entreaty is simple but urgent: ‘we need thinkers and artists who can help us temper hate and engender a greater humanity’ (p.176).

Footnotes

- Cited in P. France: Mapping Lives: The Uses of Biography, Oxford 2002, p.7. footnote 1

- P. Mishra: The Age of Anger: A History of the Present, London 2017. footnote 2

- S. Biko: I Write What I Like: A Selection of His Writings, New York 1987, p.41. footnote 3

- P. Gilroy: Against Race: Imagining Political Culture Beyond the Color Line, Cambridge 2000. footnote 4