‘What the hell’: narrative and mystery in the work of Keren Cytter

by Tilde Fredholm • June 2024 • Journal article

Introduction

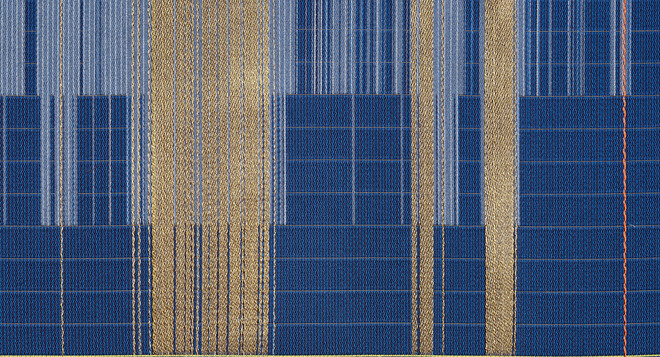

In Video Art Manual (2011), Keren Cytter (b.1977) introduces a scenario that is reminiscent of science fiction and disaster films. News reports detail an impending catastrophe, a ‘solar storm’ that threatens to eradicate electricity. The characters in the video – presented in the manner of the mockumentary genre – have various reactions to this announcement: some are paralysed by a fear of death; others busy themselves marketing a duck-shaped phone that does not rely on electricity; and a group of young people plan a rooftop dance for when the solar flares peak. Overlapping these situations, however, is a sort of parody of the infomercial format. In the opening scene, a confident, smiling man FIG. 1 declares: ‘In this informal presentation, I will try to unfold the great mysteries of these new media [languages]’.

At first, this infomercial seems to have little to do with the impending apocalypse. From this perspective, the news clips that follow FIG. 2 are examples of the ‘languages’ of popular media, of common techniques used in cinema and television. Throughout the fifteen-minute video, there is a continuing commentary on the images seen: how they are used to convey events and potentially skew meaning. Soon, however, the two narratives begin to merge: the man instructing viewers on ‘new media languages’, for example, is also marketing the new phone that will enable communication after the solar storm. Such twists and turns are fundamental to the dramaturgies constructed by Cytter; the comforts of familiar narrative structures slip away, filmic and televisual stories and tropes are disrupted and combined into something else.

Cytter is often cited as an artist who uses the medium of video to ‘break down’ or engage in ‘metacritical reflection’ on the processes of film-making and other kinds of media.1 Her work has been described as ‘non-narrative’ and, indeed, she has stated that, for her, ‘structures and the frames are much more interesting than the narrative, and the narrative is just for the audience’.2 Yet, Cytter weaves unlikely stories that lead her characters – and her viewers – down rabbit holes of perplexing plot lines and upturned expectations. She has written several Surrealist-inflected novels and finds inspiration in a broad range of literature, including the writings of Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortazár. While narrative might be a prop, joke or satire, in Cytter’s practice it also takes on a life of its own. During the 2000s she created two films based on short stories by Cortazár, an Argentinian writer often considered part of the literary genre of magical realism, alongside, for example, Borges, Alejo Carpentier and Gabriel García Marquez.3 This article will consider Cytter’s engagement with Cortazár’s writing as a way to broaden the understanding of narrative in her work. For the artist, narrative is a significant tool that, alongside her chosen means of image-making and editing, actively sustains spaces of mystery and storytelling.

‘Continuity’

Made using 16mm film as opposed to the digital formats that Cytter more commonly employs, Continuity (2005) is based on Cortazár’s short story ‘Continuidad de los parques’ (‘Continuity of parks’; 1964), in which two parallel realities – that of the story and that of its reader – are merged.4 ‘He had begun to read the novel a few days before’, Cytter’s protagonist reads aloud from a book, before he is disturbed by a phone call that angers him. He threatens and insults the person calling, inferring a love affair gone wrong or acrimonious divorce proceedings. After throwing the phone across the room, he settles back down, lights a cigarette and continues reading: ‘Word by word, licked up by the sordid dilemma of the hero and heroine, letting himself be absorbed to the point where the images settled down and took on colour and movement’.

The frame then cuts to a man and a woman outside, who are talking at odds with one another FIG. 3: he asks about the layout of a house, while she is wrapped up in a melodramatic monologue about their relationship. Having rebuked her kiss, he leaves her; there is a cut to a pair of gloved hands opening a door and the shadow of a large knife. The tension escalates until, finally, the man creeps up behind a person sitting in an armchair, in front of large windows, with a book. As he raises the knife, the seated person is revealed to be the initial protagonist FIG. 4, who reads aloud the final line from Cortazár’s story: ‘The door of the salon, and then the knife in his hand, the light from the great windows, the high back of an armchair covered in green velvet, the head of the man in the chair reading a novel’.

‘Continuity of parks’ has been described as a ‘metafiction’, and, in her work, Cytter heightens the implications of this register.5 The reader-protagonist does not read from a fictional novel, but from Cortazár’s story; there is also a suggested link between the reader and the ‘heroine’ – she might be the woman so violently insulted on the phone, an event that does not occur in Cortazár’s telling. Both story and film tamper with the boundaries that separate fictions from their consumers. In doing so, the initial mystery of an impending murder is displaced by the new mystery of the slippage between realities that has occurred. The story world is expanded, expectations are modified and the disruption in the fabric of continuity itself becomes a narrative element.

The metafiction of Continuity is different from other meta-gestures that have become signature aspects of Cytter’s work. Her films abound with wry nods to processes of acting and filming. Video Art Manual, for example, introduces subtitles that puncture the scenarios they accompany – ‘subtitles help to distract the viewer from bad acting and visual mistakes’ FIG. 5 – or inform certain effects – ‘split screen reduces the viewer’s emotional involvement’ FIG. 6. Elsewhere, Cytter’s actors and characters question their scripts and draw attention to their own performance. In writing about Cytter’s practice, references to Bertolt Brecht’s theories regularly make an appearance.6 The Brechtian term Verfremdungseffekt (distancing effects) describes techniques that prevent viewers from losing themselves in the narrative, such as drawing attention to the process of its making or having an actor address the audience directly.7 By contrast, Continuity introduces a shift that does not seem to interrupt the flow of narrative. While the conventional order of representation, or storytelling, has been undone, the ongoing narrative allows the viewer to embark on a new journey. An exploration of Cytter’s other meta-gestures often show similar – if more complex – reintegrations into a new and puzzling story-space.

‘Les Ruissellements du Diable’

Cortazár wrote stories in which reality, subjectivity or language do not offer stable categories from which to follow events. This is especially true for ‘Blow-up’ (1959), which opens with what appears to be a moment of linguistic crisis:

It’ll never be known how this has to be told, in the first person or in the second, using the third person plural or continually inventing modes that will serve for nothing. If one might say: I will see the moon rose, or: we hurt me at the back of my eyes, and especially: you the blond woman was the clouds that race before my your his our yours their faces. What the hell.8

In ‘Blow-up’, a man – referred to variously in the first person and as Roberto Michel – recounts how, when on a walk around Paris to take photographs, he witnesses an awkward encounter between a woman and an adolescent boy in a park. He takes their picture, which disturbs them and causes the boy to run away. As Roberto is arguing with the woman about photographing them, it becomes clear that another man, observing the situation from his car, is somehow linked to her. Arriving home, Roberto develops his film and is so pleased with the image of the boy and the woman that he enlarges it and pins it on his wall. What ensues is a mounting obsession with the truth of what occurred that day. Both aided and frustrated by the photograph’s inability to complete, or bear witness to, the moment of ‘reality’ that is captured, Roberto becomes trapped in a spiral of unresolved retellings, ending with a complete unmooring of his consciousness from the reality he so desperately seeks to grasp. At the end of ‘Blow-up’, as in the beginning, the narrator is described as literally floating in the air, and their ruminations concern the sheer impossibility of telling a story in any capacity.

Cytter used ‘Blow-up’ as the foundation for her film Les Ruissellements du Diable (The Devil’s Streams; 2008), which is the French title of Cortazár’s story.9 She changed some aspects of the narrative but retained its erotic fixation and disrupted agency, as well as the oscillation between two discursive focal points. These are integral elements of the story; Cortazár spent as much time ruminating on the intangibility of reality as seen (photographed) or told (narrated) as he did in developing the growing obsession of its protagonist.

Les Ruissellements du Diable opens with a character named Michèlle, who introduces herself to the audience. In the following scenes, Michèlle and an unnamed man alternatively perform the same actions in the same space. They do not share this space – apart from in one short clip, approximately five seconds long, during which the man’s arm reaches to unbutton Michèlle’s blouse FIG. 7 – rather, they are subjects of the same scenario. They both develop a photograph FIG. 8, pin it on the wall, smoke and masturbate. Voiceovers explain that they are back at a motel, looking at the photograph that they have enlarged.

There are three distinct voiceovers that only occasionally sync up with one of the characters. They hint at something observed or triggered, something that cannot quite be put out of mind – as Michèlle states ‘I think my body is resisting the image’. Match-cuts show them repeating or taking over each other’s gestures. For example, we see the man reach for a cup, followed by a close-up of his hand; the next cut reveals Michèlle picking it up.

Next, the characters are transported to the park where the photograph was taken, where they are seen having a furtive interaction FIG. 9. The film then unfolds in repetitious circuits around their meeting, creating a self-contained world that repeats itself with only minor alterations. After the first encounter, the protagonists are again in their room, smoking, masturbating, drinking cups of coffee and looking bored. As before, their actions are presented as co-continuous, unfolding in the same space that they do not share. They see each other in a bar at night, then return, alone again, to their room; once more they meet in the park, after which the video concludes in the motel, where the lights are being turned off one by one.

Les Ruissellements du Diable is bookended by appearances of Michèlle on a television screen. In the opening scene she makes a statement about the man who is watching her, who, she says, ‘is in love with me’ and ‘imagines my words’ FIG. 10. In the final scene she talks about the version of herself in the film: ‘Michèlle discovers that she doesn’t exist, any more than the man who loves her’. The statement suggests a fantasy, but one that has become unmoored from a singular subject or perspective. In the end, the scenario of the fantasy is more concrete than its participants: ‘While taking her eyes off the picture she took, while touching her body or picking up the phone, Michèlle understands that she is endlessly reading this moment, eternally translating and presenting this non-particular story’. Rather than being agents driving a scenario to its conclusion, the characters are at the mercy of a scenario that is never quite fulfilled.

Cytter has explained a similar logic in relation to her work Killing Time Machine (2018): ‘plot creates the illusion that it is operating the shots, although the shots are operating the story’.10 Narrative is rarely a prioritised framework for the artist, who mostly begins a new work by considering visual ideas, formal conceits or possibilities offered by the camera and processes of video editing. She has elsewhere emphasised that, more often than not, one comes before the other: ‘I cannot continue [an idea] if it doesn’t have enough rules. I need to have more rules and more framing [...] [Narrative] is a way for the images to come together – my excuse for it’.11

Narrative and video

‘Generally’, Cytter has said, ‘I’ve never cared much for creating a narrative that endears me to the viewer – traditional character development, for instance, or communicating some idea of an authentic experience’.12 Born in 1977 in Tel Aviv and today based in New York, Cytter began her career as an artist in the late 1990s. She is best known for her video works, to which she refers interchangeably as movies, films and videos. She typically uses video or digital cameras (with exceptions) but has nonetheless referred to herself as a ‘language artist’.13 Almost all of the artist’s videos, currently numbering over sixty, can be seen in full on her Vimeo account.

Cytter exemplifies the generation of video artists who came of age during the transition from video to digital technologies. Writing in 2006, Michael Rush considered how for some time artists using video had been moving away from the medium specificity highlighted by earlier generations.14 His idea of the umbrella term ‘filmic art’ has since been used to describe the many recategorisations of artists using moving images and a variety of technologies to produce them. Yet video has always been the central technology of Cytter’s practice, and many aspects of her ‘reflexive’ techniques find their roots in the medium’s history. When video emerged as an offshoot of television technology in the mid- to late 1960s, many of its practitioners saw it as uniquely positioned to critique and deconstruct how images and text were seen in broadcast media.

The immediacy of video also proved to be a counterforce to film, which relies on a chemical process to be realised. Chris Meigh-Andrews (b.1952) has described the emergence of an ‘oppositional practice’ in the 1960s and 1970s focused on ‘deconstruction’ and ‘demystification’.15 Contemporary critical theorists – from Guy Debord to Stuart Hall and Laura Mulvey, to name a few – developed ideas about how mainstream cinema and television presented deeply ideological or culturally specific ideas as natural, universal and inevitable. These included an easily replicable narrative mode, the structure of which viewers could recognise across different types of images and themes, often stringing events together in cause–effect relationships that unfold in a unified time and space.

Cytter’s approach to the clichés of cinema, however, is not straightforwardly one of unmasking: ‘A cliché for me is an absolute truth’.16 Although her early works invoked comparisons with the Dogme 95 movement, her practice does not align with the ‘vows’ that Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg set out for themselves in 1995 to move away from the hypnotic sheen of Hollywood.17 Cytter’s works do little to glorify naturalness; they are extravagant and additive, full of poetic voiceovers, music, ‘superficial actions’, genre references and many other elements that go against the Dogme ethos of ‘chastity’.18 Rather, she ‘samples’ scenarios, tropes and dialogues from a broad range of media sources, especially mainstream cinema and television, adapting their generic plot points and exaggerated emotional displays for her own settings.19 By extracting such clichés from their contexts, Cytter draws attention to the extreme dramatisation of actions and emotions in popular media, and the absurdity of such reactions in everyday life. But she also establishes a shared space with the viewer. As Naomi Beckwith states:

Cytter’s work depends on the fact that art audiences are mass-media consumers. Taking on ubiquitous, grand themes – love, family life, career, jealousy, war, death and alienation – Cytter’s videos are legible to her audiences because filmmaking techniques are a shared language.20

Mystery for mystery’s sake

In the essay ‘El arte narrativo y la magia’ (‘Narrative art and magic’), published in 1932, Borges – one of the creators of what would become known as the genre of magical realism – presented his own analysis of narrative approaches. He considered a ‘psychological variety’, framing ‘an intricate chain of motives similar to those of real life’. More popular varieties, he continued, such as belonging to the ‘adventure novel [...], short story, and those endless spectacles composed by Hollywood’ are ‘governed by a very different order, both lucid and primitive: the primaeval clarity of magic’.21 For Borges, these kinds of narratives do not offer realistic continuity, but rather sequences of premonitions that have to be fulfilled as the story is woven: ‘a rigorous scheme of attentions, echoes and affinities’.22

Studying magical realist literature as it developed over the twentieth century, Wendy B. Faris has shown how writers of the genre use narrative not simply to dictate cause and effect, but also as a means of cumulation – of pulling together images and ideas, beliefs and phenomena of all varieties. As such, narrative offers a neutral space that ‘abolishes the antinomy between the natural and the supernatural on the level of textual representation’, while retaining their essential difference.23 Magic, mysterious happenings or changes in time, space and identity can thus be incorporated into the flow of a story, without necessarily losing the sense of something that is, in Faris’s words, ‘irreducible’ to pre-existing logics and expectations.24

As a result, the narrative voice in magical realism is flexible. Neither omnipresent nor subjective, it wanders between different elements of the text.25 In Cortazár’s ‘Blow-up’, for example, who is telling the story of Roberto’s travails? The story presents two points of view, which, even though using the same voice, stand in an inexplicable relation to one another. The disorientation initiated here is replicated in Roberto’s predicament of not understanding – or understanding too much – what he has seen. Chronological narrative is deprioritised in favour of other kinds of intimations and cumulative conveyances.

Cytter’s Les Ruissellements du Diable also follows a formal structure that disinvests in a conventional depiction of events. Nonetheless, connections are still provided and narrated, engaging the viewer to infer meaning and context – recalling Borges’s ‘attentions, echoes, and affinities’. Like ‘Blow-up’, Les Ruissellements du Diable presents time, space and perspective as fractured. The two protagonists are synonymous: they exist in the same space, where they perform the same actions. Mainstream cinema has, in its own way, familiarised us with this type of montage, which often connects people before they have even met. However, each time Cytter’s characters meet, their love, or reason for their relationship, is deferred. Actions are spoken but not performed, or they are reversed from one scene to the next. For example, a bottle that the man knocks over in an early scene is picked up by Michèlle in a later one FIG. 11.

We follow them as if on a Möbius strip.26 The story unfolds until a structural turn brings us back to an earlier moment, now observed from a new angle. Within this, certain inescapable background facts – like that of the solar storm in Video Art Manual – remain and evolve. The photograph is enlarged; it relates somehow to an experience or memory; there is mounting frustration around this experience, which might be a fantasy or might be real. Strengthened by the looping and folding narrative, a scheme is built up, consisting largely of premonitions. The photograph leads to the scene in the park, as the autoerotic activity preludes the lovers’ meeting. Cytter narrates a parable of sexual frustration and social alienation, in which the continuation of an act takes precedence over physical limitations and epistemic logic.

In a 2010 essay, the curator Magnus af Petersens described Cytter’s narratives as ‘formal devices’ that ‘generate meanings and say something about the human condition in our time’.27 Her films are carefully scripted, and although it may appear that performers or images step outside the bounds of a devised world, they very rarely do: ‘what we see in Cytter’s films is language, the script, controlling the world, reality’.28 To suggest that her work deconstructs cinematic illusions, alerting the viewer to the reality to which images are secondary, assumes that, for her, and, perhaps, for our media-saturated world at large, such a world still exists. Indeed, Video Art Manual demonstrates the horror of returning to such a world; the ‘new media languages’ that are under threat also include Cytter’s art practice. Without them, there is only the menacing duck phone, which will not stop ringing FIG. 12. Who might it be? In a similar way, Cytter’s adaptations of Cortazár fold reality and representation into each other, but without fretting about either’s ‘true’ identity. What seems to matter to Cytter is the ‘irreducible’ sense of mystery derived from such stories, updated in her work to appeal to the indiscriminate media consumer.