‘Sorprendente hallazgo’ (‘Chance find’): Alan Glass and contemporary Surrealism in Mexico

by Abigail Susik and Kristoffer Noheden • June 2021

The imposing assemblage Ziggurat polar stands 163 centimetres tall FIG. 1. Contained in a rectangular box, the work’s central feature is a found print of an ice castle with gun fire and fireworks erupting in arcs. At the bottom are two wooden plaques, one of which is painted red and says ‘VIVA’, the other one is painted green and says ‘MEXICO’. Ascending through the middle of the work are a series of affixed objects, including a small wooden box with two miniature croissants overlapping to form an X and two dice showing three and six; a sign announcing the Cirque d’Hiver at Boulevard du Temple in Paris; and two flat cardboard figures facing one another and holding hands at arm’s length. Finally, an enormous erect penis and two breasts made of clay are attached to the body of the woman who crowns the ice castle. Combining references to nineteenth-century Montreal, Mexico’s Independence Day and the city of Paris, Ziggurat polar resounds with transcultural exuberance. It is a poetic treatment of the sense of multiple belongings of its maker: Alan Glass.

Glass was born in Montreal in 1932. He studied painting with Alfred Pellan before moving to Paris in 1952 to study art and anthropology. There, his intricate ballpoint pen drawings were discovered by the Surrealists André Breton and Benjamin Péret, who organised his first solo exhibition at Galerie Terrain Vague in 1958. However, while he has continued to paint and draw, producing highly detailed works, assemblage has been Glass’s preferred medium since the early 1960s. Having moved to Mexico City in 1963, Glass has long been a naturalised Mexican citizen and has played a significant part in the Mexican Surrealist art scene, alongside artists such as Leonora Carrington, Pedro Friedeberg, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Bridget Tichenor. Now aged eighty-eight, Glass works almost daily in his combined home and sprawling studio in Roma Norte, Mexico City. In 2017 he received the prestigious Medalla de Bellas Artes from Mexico’s ministry of culture in recognition of his achievements, but in Europe and North America, Glass is still little-known.

In this essay the present authors analyse the history of Glass’s move to Mexico and his entrance into that artistic community, before proceeding to place his work in the context of Surrealist assemblage and explore the ways in which it speaks to questions of displacement and migration. Glass is entrenched in the history, ideas and networks of Surrealism, but his art is specifically shaped by Mexico and Mexican contemporary art. Although Surrealist notions of the object and assemblage occupy a prominent place in recent theory, the wider history of Surrealist assemblage is largely uncharted.1 Alongside Aube Breton-Elléouët in France, Jan Švankmajer in the Czech Republic and Friedeberg in Mexico, Glass is one of the most consistent and inventive contemporary makers of Surrealist assemblage. As indicated by Ziggurat polar, his is a transformative practice, in which memories and multiple places of belonging are reassembled and reinvented.

Embarkation for Mexico

Alan Glass had been in Paris for a decade when he undertook his first journey to Mexico in a year-long foray between 1961 and 1962.2 His desire to visit Mexico arose primarily as a result of a lifelong artistic and anthropological interest in culinary traditions from diverse cultures, in particular folk practices in which elaborately decorated candies, baked goods or special dishes were created during holidays, festivals or religious celebrations. As a child growing up in the Montreal area, he was deeply impacted by an experience he had at a rural French-Canadian wake for an infant, where he gazed at a child’s body decorated with flowers and white chicken wings and was overwhelmed by the smell of boiled milk that pervaded the room.3 This experience triggered a lasting fixation with themes of ritual adornment, spiritual and physical nourishment, celebratory mourning and the interconnectedness of birth and death, which have remained palpable concerns in the artist’s œuvre over the past seventy years FIG. 2 FIG. 3.

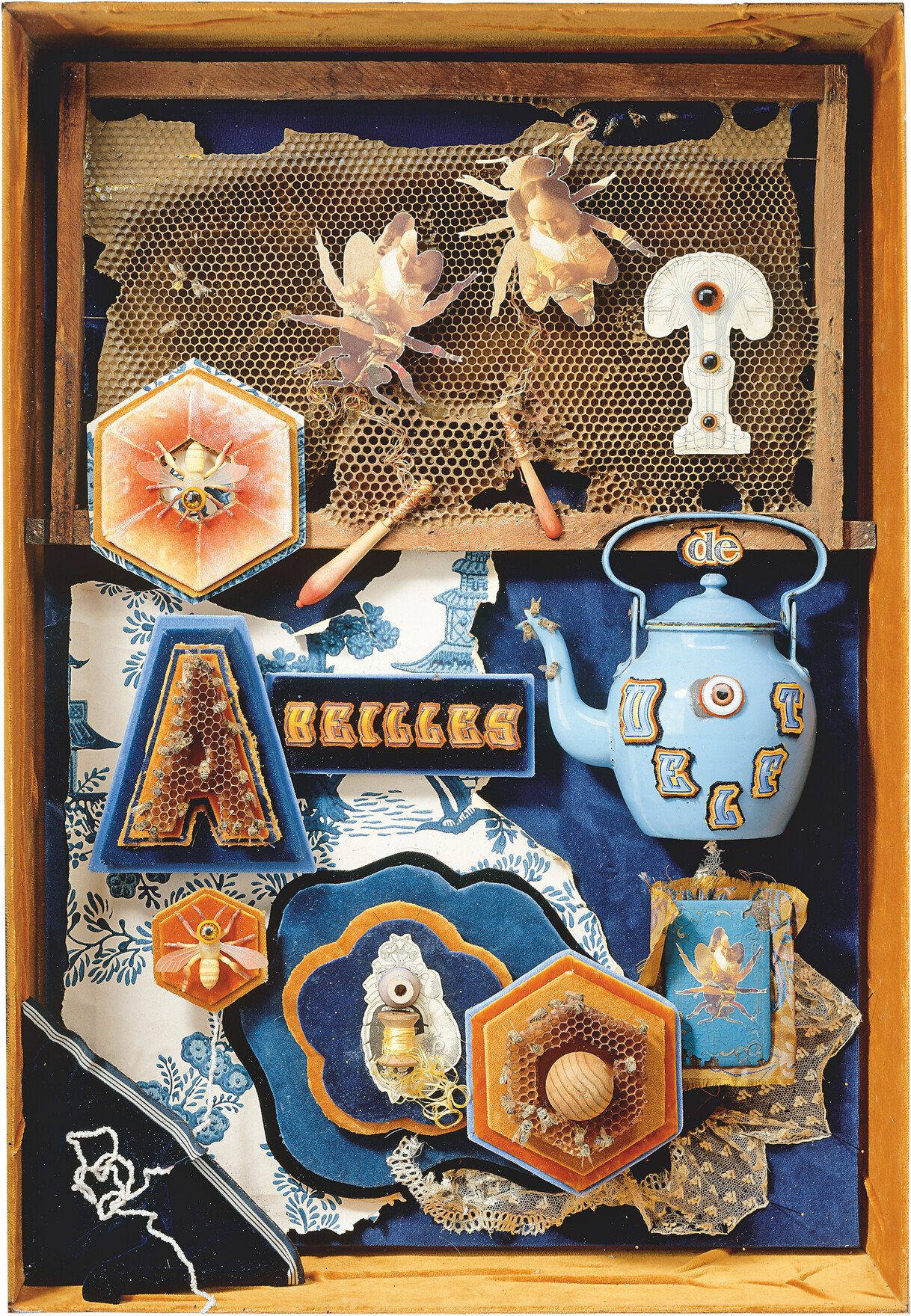

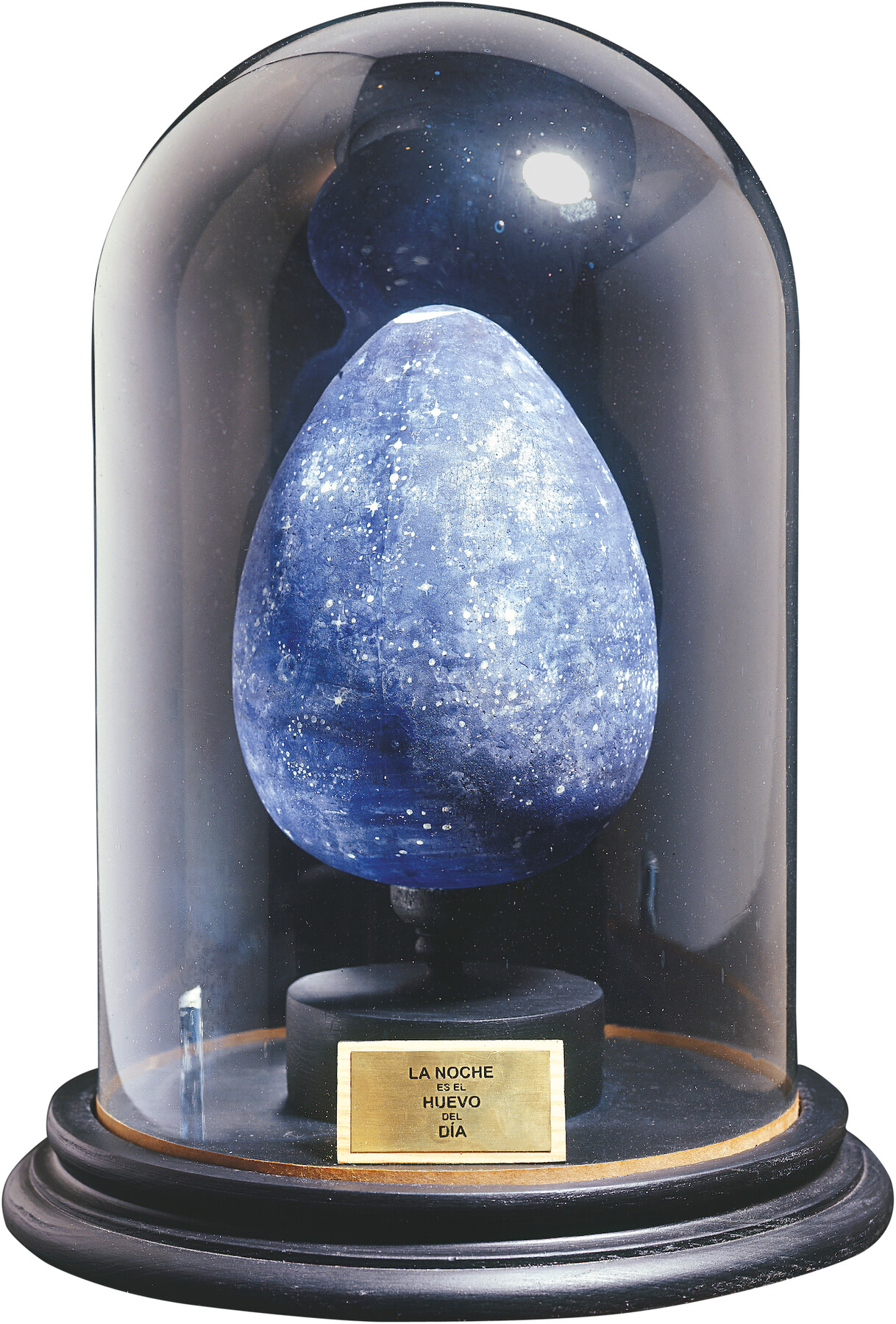

Glass’s attraction to folk food traditions was reignited through a series of trips to Eastern Europe, Greece and the Middle East. He developed a passion for collecting intricately painted Easter eggs called kraslice in Czechoslovakia or hímes tojás in Hungary, as well as the finely ornamented breads associated with wedding rites and saints’ days in the bohemian and Orthodox cultures of Eastern Europe.4 He also became interested in the popular arts of rural France, such as hand-carved wooden beehives found in Normandy, designed so that bees enter the hive through the mouth of a carved face or the breasts of a hewn female form.5 Glass featured a photograph of one of these Norman apiaries – festooned with three male busts modelled out of the wood of a massive tree trunk to which they were still attached – on the cover of the brochure for his first solo exhibition at Galerie Le Terrain Vague in Paris, 1958. The hexagonal structure of the honeycomb with its repetitive pattern, the unctuous viscosity of honey as evocative of life force and the all-powerful symbolism of the queen are all significant motifs that have recurred throughout Glass’s practice, just as the egg’s associations of rebirth and fertility are central to his aesthetic FIG. 4 FIG. 5.6

It was after returning from a sojourn in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1950s that Glass first became aware of Mexican food traditions, which thereafter exerted a profound effect upon his art and life.7 Visiting the studio of his good friends Yves Elléouët and Aube Breton-Elléouët, he held a Mexican sugar skull for the first time. The brightly embellished Día de los Muertos candy skull, with its ‘kitsch beauty’ and macabre vividness, fascinated Glass so intensely that he boarded a Barcelona cargo ship bound for the Gulf coast port of Veracruz, from where he travelled to Mexico City.8 Another reason that Glass may have felt compelled to undertake a journey to Mexico in 1961 was the fact that his friends – the Chilean performer, writer and director, Alejandro Jodorowsky and his wife, the French actress Denise Brosseau Jodorowsky – moved there on a part-time basis in 1960.9 Jodorowsky arrived in Paris from Chile a year after Glass and the two grew close enough that the artist later invited him to write the short text for his Galerie Le Terrain Vague exhibition.10 Working as a mime in Marcel Marceau’s travelling company, Jodorowsky first visited Mexico City in 1957, where he quickly became a devoted acolyte of the British Surrealist Leonora Carrington and established contacts in the experimental theatre scene. In these early days of their friendship and collaboration, Jodorowsky and the elder artist undertook a symbolic ceremony of spiritual union in which they simultaneously devoured sugar skulls embellished with each other’s names.11 When Jodorowsky returned to France in the late 1950s, just in time for Glass’s Surrealist-curated exhibition at Galerie Le Terrain Vague, Glass must have been apprised of his friend’s recent adventures and theatrical productions in Mexico, possibly impacting his own decision to forge a path across the Atlantic and heightening his fascination with sugar skulls.

When Glass arrived in the Mexican capital in early summer of 1961, he stayed at Jodorowsky’s apartment on the Calle de Berna in the Zona Rosa of the Juárez district. In time, he became acquainted with a number of artists including the American textile artist Sheila Hicks, the Japanese conceptual artist On Kawara and Surrealist expatriates Remedios Varo, Kati Horna and Carrington.12 Glass continued to produce a series of two-dimensional works of art during this period, most of which are now lost, although roughly comparable examples from 1963 survive, demonstrating the artist’s delicate palette and mysterious iconography FIG. 6 FIG. 7.

At this time, Jodorowsky was collaborating with Carrington on the Mexican premiere of her ‘noir juvenilia’ play Pénélope, for which Carrington designed the sets and costumes with motifs including the tarot-derived image of a hanged man and the disembodied heads of hybrid creatures.13 This dramatisation of Carrington’s longtime interest in pastiched children’s genres and themes of monstrous hybridity may have appealed to Glass, who became an intimate of hers in the mid-1960s. Like the Mexican sugar skulls that Glass so prized and the pan de muertos that he had recently discovered, Carrington’s aesthetics evoked an explosively paradoxical ambiance of innocence and foreboding.14 Moreover, since Carrington’s relocation to Mexico from Europe and New York in 1943, her work had increasingly begun to contemplate and address the compelling resonances she found between her artistic practice and the Mexican culture that surrounded her.15 Although Glass and Carrington did not begin to spend extensive time together until after he moved to Mexico in 1963, Glass’s immediate captivation with the popular arts of this country laid the groundwork for their future friendship. In summer of 1962, he briefly returned to France with a large collection of Mexican folk art and a desire for an imminent return voyage. Soon thereafter, Glass would begin to develop his highly distinctive large-format assemblage practice, resulting in a now-lost object from 1965 made out of Mexican sugar skulls.16

Returning to and remaining in Mexico City

By March 1963 Alan Glass had settled into his own rooftop apartment near Chapultepec Park in Mexico City, just as the Mouvement Panique (Panic Movement) that Alejandro Jodorowsky had initiated with Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor in 1962 began expanding on an international basis.17 Glass’s explorations of Mexican culture and his new surroundings formed a dynamic dialogue with his own evolving practice as a young artist still in his early thirties. As the scholar Masayo Nonaka has pointed out, his voyages in Mexico over the course of the 1960s resulted in an abiding admiration for the unique combination of Baroque and folkloric traditions found in many post-conquest buildings and architectural features there.14 Influenced by the indigenous Baroque style of structures such as the church of Santa Maria Tonantzintla near Puebla, with its brightly painted exterior and densely encrusted interior, Glass rapidly developed a robust assemblage practice.19

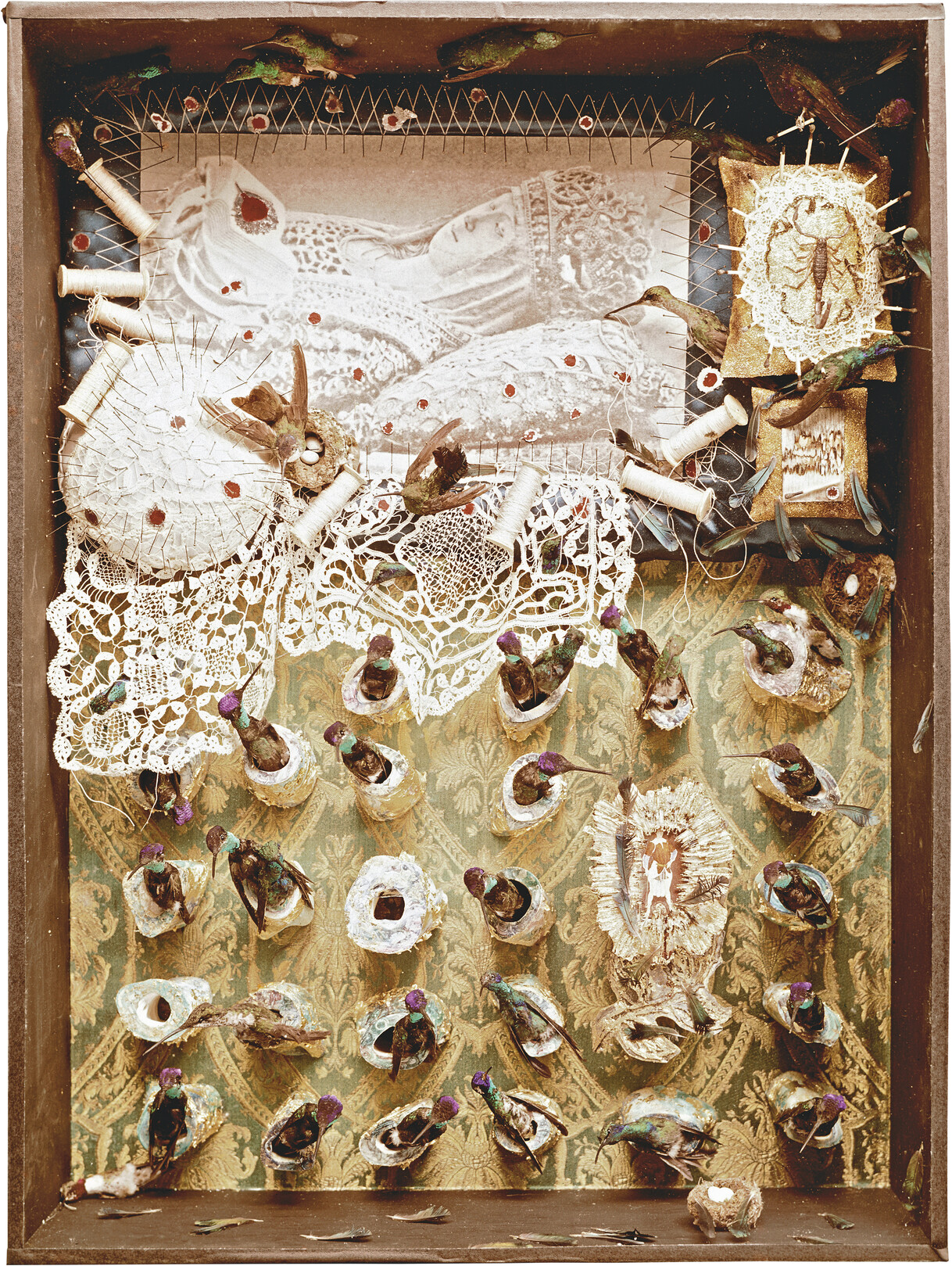

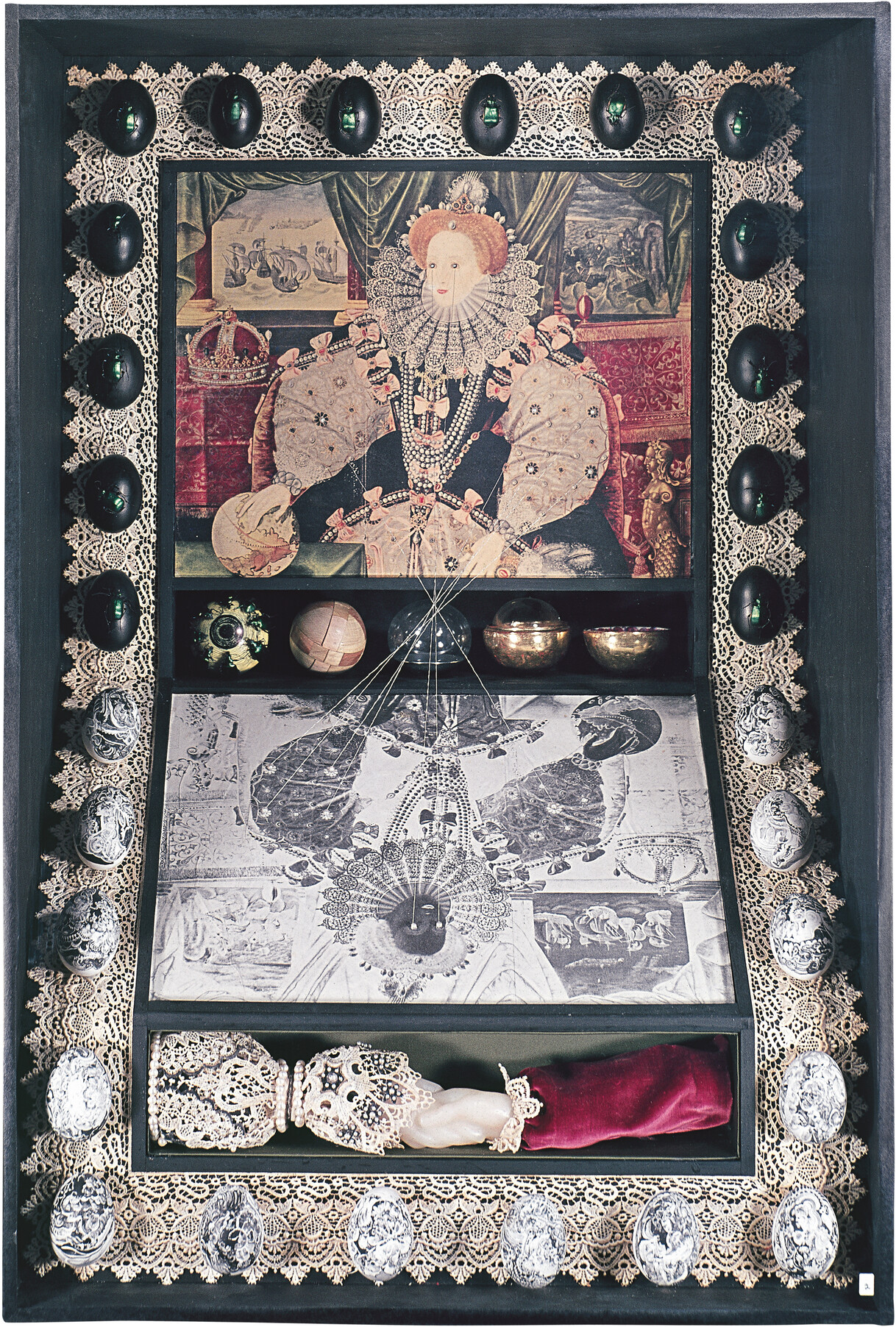

Glass scoured Mexican mercados and mercadillos in search of evocative materials, discovering locally distinctive items such as stuffed hummingbirds. For example, his 1964 assemblage Birds of Bones contains approximately forty taxidermic hummingbirds arranged in a delicate tableau vivant of nests, which has been further enlivened by a wallpaper background, a photograph of an enshrined female saint, lacework, bone sections, a scorpion on a pincushion, needles and unravelled spools of thread FIG. 8. Contemporary works from this period such as Nouvelle rosée, nouvelle miel, which was shipped to Byron Gallery in Manhattan for Glass’s first group show in 1964 (also featuring works by Joseph Cornell, Andy Warhol and others), incorporated a honeycomb with dead bees strewn across it, surmounted by a reproduction of the famous late sixteenth-century Ditchley Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I and rows of decorated eggs FIG. 9.

Both of these early assemblages, with their focus on historical women’s fashion, the associations between femininity and aspects of animal life and death, and their distinctive camp mortuary aesthetic, set the tone for the frequent exploration of gender signifiers and associations in Glass’s object-based œuvre. In general, Glass’s assemblages tend to approach gender identifications through found objects and materials that reference outmoded decor, pre-modern culture, memento mori, the brocaded trappings of monarchical pomp or the morbid death rites of sacred religiosity. Such an orientation sets Glass apart from many of his Surrealist predecessors and contemporaries. Unlike much Surrealist art, it is not necessarily erotic desire for the beloved’s idealised body that comes to the forefront as a dominant preoccupation in Glass’s assemblage practice, although certainly a Duchampian conceptual eroticism is also an important theme in the artist’s œuvre. Rather, assemblages by Glass such as Birds of Bones and Nouvelle rosée, nouvelle miel generate a modulated portrayal of the female gender as subject to a different type of object worship: that of sublime maternal devotion, the esotericism of ecstatic virgin cults or the saintly apotheosis of the carnal body in holy death.

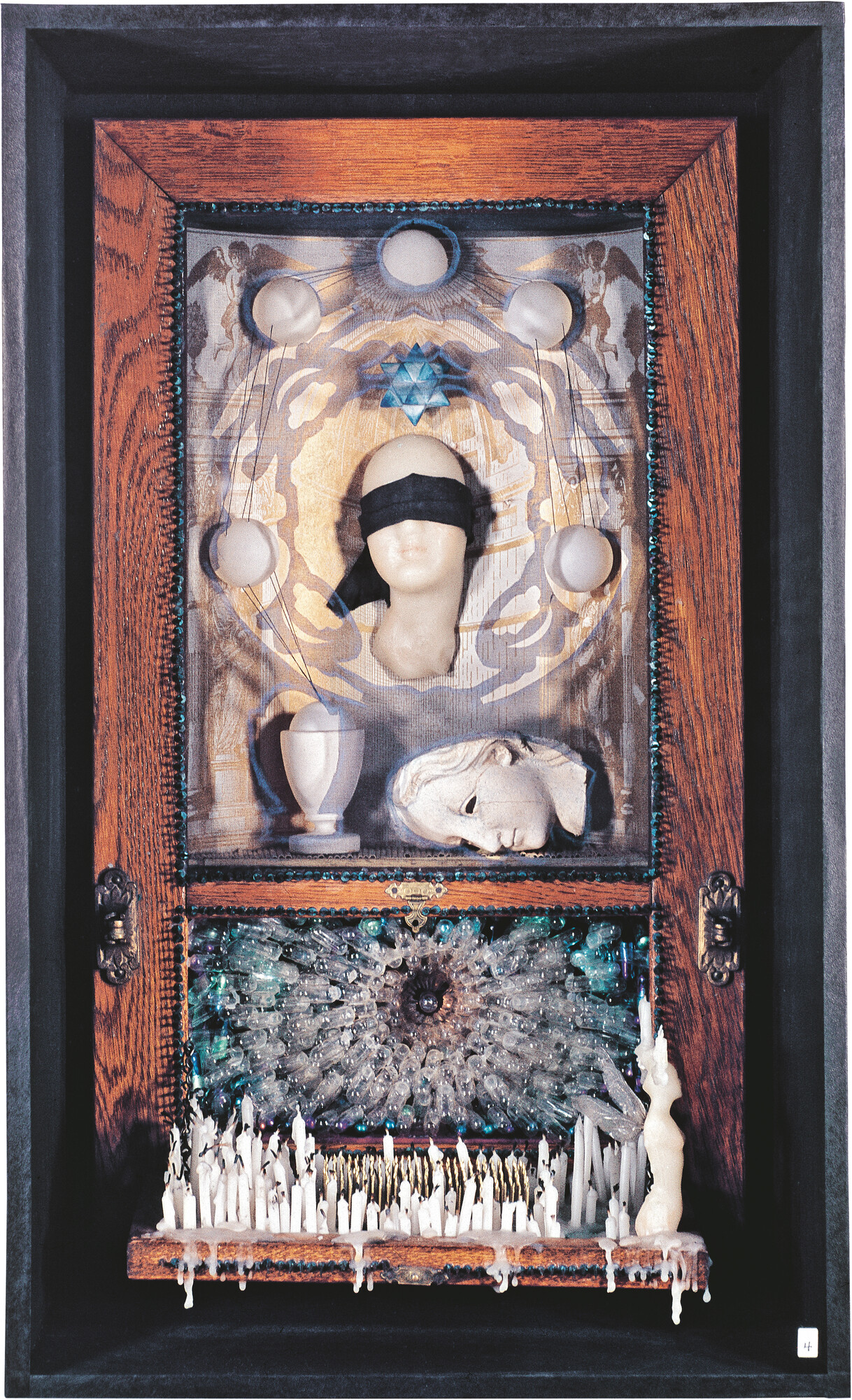

Glass began to systematically incorporate Mexican motifs, patterns and iconography into his assemblages by at least 1967, when his first solo exhibition in Mexico, Los Relicarios, opened at the Galería Antonio Souza in the Zona Rosa. As suggested by the title of this exhibition, which garnered substantial attention from the press, most of the assemblages on display were formal meditations on the many reliquaries, shrines and altars found in Mexican Baroque churches and cathedrals. Pieces such as Untitled (1966) accentuate the latent eroticism sometimes found in the melancholic atmosphere of sacred spaces FIG. 10. Here, a blindfolded wax mannequin head is encircled with a halo of interconnected white spheres and crowned with a suspended aquamarine dodecahedron.

Soon after resettling in Mexico City, Glass began to befriend a circle of contemporary Mexican artists, writers, gallerists, performers and musicians: Manuel Felguérez, Lilia Carrillo, Pedro Friedeberg, Luis Urías, Pita Amor and Tere Pecanins, among others. These figures are often associated with the Generación de la Ruptura (Breakaway Generation) of the 1960s, who reacted critically to the cultural dominance of the Mexican muralist movement.20 In 1967 the sculptor and painter Manuel Felguérez hired Glass to spend a year researching and travelling in Mexico in preparation for an exhibition of the popular arts of the Americas to be held in Spain. Glass voyaged throughout Mexico, visiting Mayan ruins for the first time – a pivotal experience for the artist – and collecting folk art objects such as huge papier-mâché Judas sculptures, rustic carvings and ex-votos of different kinds.21

In 1967 Glass was also featured as a ‘minaturesco y obsesivo’ (‘miniaturesque and obsessive’) artist in Ida Rodríguez Prampolini’s important El Surrealismo y el arte fantástico de México exhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City.22 Five assemblages, including Reina Isabel con escarabajos FIG. 11, were hung alongside contemporary selections by Mexican artists such as Alberto Gironella and Friedeberg, both of whom possessed their own concrete connections to French Surrealism.23 In a section of the exhibition catalogue entitled ‘The desire for internationalization’, Prampolini wrote:

Alan Glass does not dare to mock like Friedeberg, nor to utter aesthetic insults like Gironella [. . .] Glass prays quietly and, when the words are missing, he resorts to the magical exorcism of a material whose beauty is not only exterior, but is hidden behind the evocative mystery of the fear of the unknown, that great question.24

A painting of fantastic creatures entitled Será cierto? (1964–65), by the British Surrealist Bridget Bate Tichenor, who soon became one of Glass’s dearest friends, was published in the same section of the catalogue. Works by Varo, Carrington, Horna and other Surrealists living in Mexico were also featured in the exhibition, providing a crucial context for Glass’s identity as an expatriate artist who deeply valued his explicit and implicit connections to both local and international Surrealist predecessors.

Despite a two-year journey to India, Nepal and Sri Lanka, Glass’s work garnered increasing acclaim in Mexico and abroad during the early 1970s, with solo exhibitions in Mexico City and Montreal in 1972, four group shows in Mexico between between 1970 and 1976 and a major solo exhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1976. Throughout this era, Glass was an integral part of the contemporary art scene in Mexico City, undertaking projects and collaborations with longtime contacts. These included Jodorowsky, who featured a montage of his assemblages in the opening credit sequence of his 1973 cult film, The Holy Mountain, and Carrington, who published a text in honour of Glass for his 1972 Galería Pecanins show in Mexico City.25

Late Surrealist assemblage: from Paris to Mexico City

Glass’s 2001 assemblage Feast of the Great Transparents is constructed from three light bulbs placed on a white porcelain plate; the sockets of the two smaller light bulbs are tied together and equipped with paper frills, while the plate is decorated with two twigs with green leaves FIG. 12. Although the work is a quintissential Alan Glass object – with its delicate construction, combination of immediacy and mystery, marked sense of humour, and quiet yet radiant eroticism – its authorship is destabilised in a way that is characteristic for Surrealist assemblage in general and Glass’s works in particular. Visually, Feast of the Great Transparents alludes to Meret Oppenheim’s 1936 object Ma Gouvernante, in which a pair of high-heeled shoes are tied up to resemble a turkey on a silver platter. The title of Glass’s assemblage is a reference to André Breton’s ‘new myth’ that centred around the ‘Great Transparents’: huge translucent creatures surrounding us that are intended to dethrone humans from their position as self-imposed rulers of the world.26 Colliding intertextual references to Oppenheim’s object with Breton’s myth, Glass self-consciously indicates his own position in a Surrealist lineage of poetics and thought, desire and humour. He also offers a striking visual paradox that bewilders the senses: a meal that is fragile yet ripe with the promise of illumination, hinting at the spectral beings who would feast upon these shards of glass, pieces of glowing wire and green leaves.

Feast of the Great Transparents is indicative of the way in which Glass partakes in and renews a Surrealist tradition of object-making. When he made Feast of the Great Transparents in 2001, Glass had been constructing assemblages for four decades. Arranged in custom-made boxes, found wooden boxes, vitrines or bell jars, his intricate works are often compared with that of Joseph Cornell, an artist he considers to be like a ‘brother’.27 The two artists certainly share a similar sensibility, including a tendency to conjure up the spectres of magical childhood worlds, as well as a fine-tuned sense of the interplay of colours and shapes. However, Glass’s technical as well as thematic range is broader than that of his American predecessor. His erotic and playful sense of humour recalls the enigmas of Marcel Duchamp, who Glass often references – either openly or obliquely. He is an artist well-versed in the history of the Surrealist object and his assemblages can be readily placed into a genealogy that includes Man Ray’s Dada works, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró’s Object (1936) and André Breton’s poem-objects.28

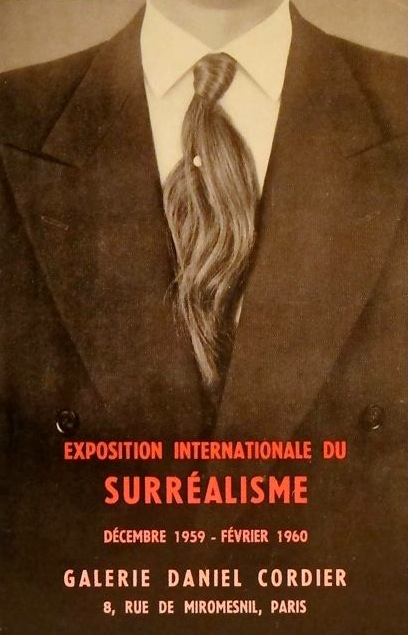

However, Glass’s initial turn to assemblage was likely prompted by lesser-known tendencies in the making of Surrealist objects during the 1950s. In particular, works by his friend Mimi Parent exerted a strong influence. Parent’s Masculin Feminin (1959) was reproduced on the poster for the erotically themed 1959–60 Exposition inteRnatiOnale du Surréalisme (EROS) in Paris FIG. 13 and its use of human hair is echoed in several of Glass’s objects, including Chinatown: Homenaje a Vincent Price (2011), which includes a braid as its central feature. Glass visited the EROS exhibition, where he would have seen an installation by Parent described as ‘a reliquary to fetishism’, which comprised a wall of works of art including Parent’s own Masculin Feminin, Oppenheim’s assisted ready-made The Couple (1959) and Adrien Dax’s Reliquary (1959).29 Dax’s bust, which is embellished with jewellery, polished stones, a bejewelled photograph of a woman’s bare breasts, dripping candles and a dragonfly brooch, resonates in particular with Glass’s 1960s assemblages, many of which take the form of reliquaries.30 Much like Dax’s work, the aforementioned 1966 assemblage makes prominent use of candles and melted wax alongside an eerie mannequin’s head.

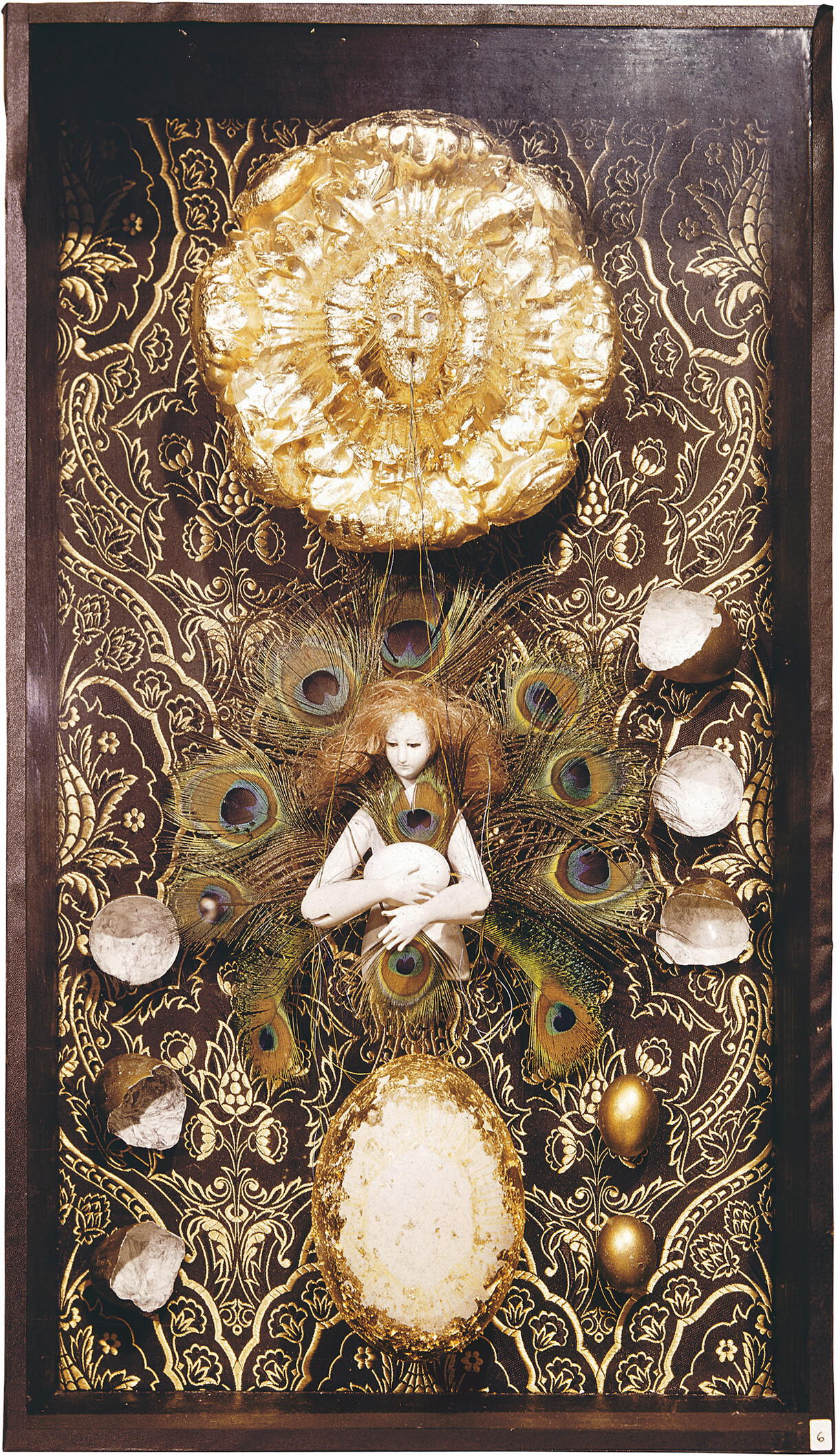

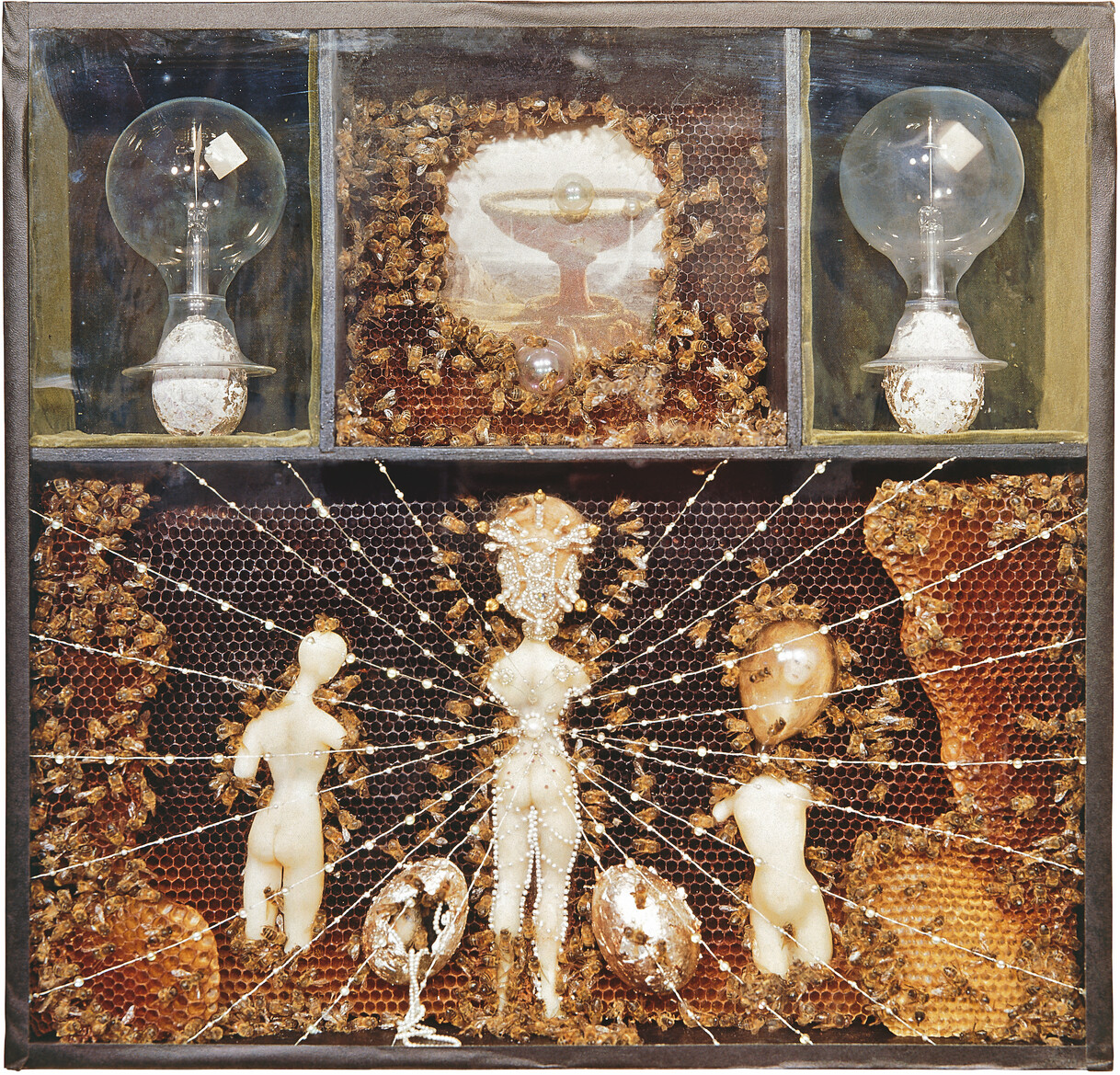

Two untitled boxes are centred around hieratic female figures FIG. 14 FIG. 15. In the earliest of these, a legless woman hugs an egg and is surrounded by peacock feathers and eggshells; in the work from the following year, three female dolls are partly submerged in honeycomb, dead bees littered around them, while three compartments above hold light bulbs and a small reproduction of Thomas Cole’s 1833 painting The Titan’s Goblet.31 The bodies of these women are seemingly undergoing a process of merging with peacocks and bees. Their corporeal form on the verge of disintegration, they approach a new state of unity with the surrounding eggs, honeycomb, opulent feathers and myriads of wings. The women on display in these works recall earlier Surrealist works such as the mannequins on parade in the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris. There, each artist altered a mannequin’s appearance in a different way – for example, Wolfgang Paalen affixed a veil, mushrooms and a bat to his; Sonia Mossé favoured a scorpion, a beetle and moss; while André Masson adhered a flower-decorated gag across the mouth and a birdcage over the head of his. But Glass also evokes a later, more sacralising Surrealist tradition of figuring women to be a locus of utopian transformation and the promise of spiritual upheaval, which draws on ancient Goddess worship and mythical female figures, such as Mélusine and Hecate, to dream of alternatives to the patriarchal order.32 The combination in these works of sacred and sexual, spiritual and corporeal, death and rebirth, is marked by Mexican material culture, but also aligns Glass with the expanding Surrealist assemblage practice of the 1950s and 1960s in Europe, the United States and Mexico.

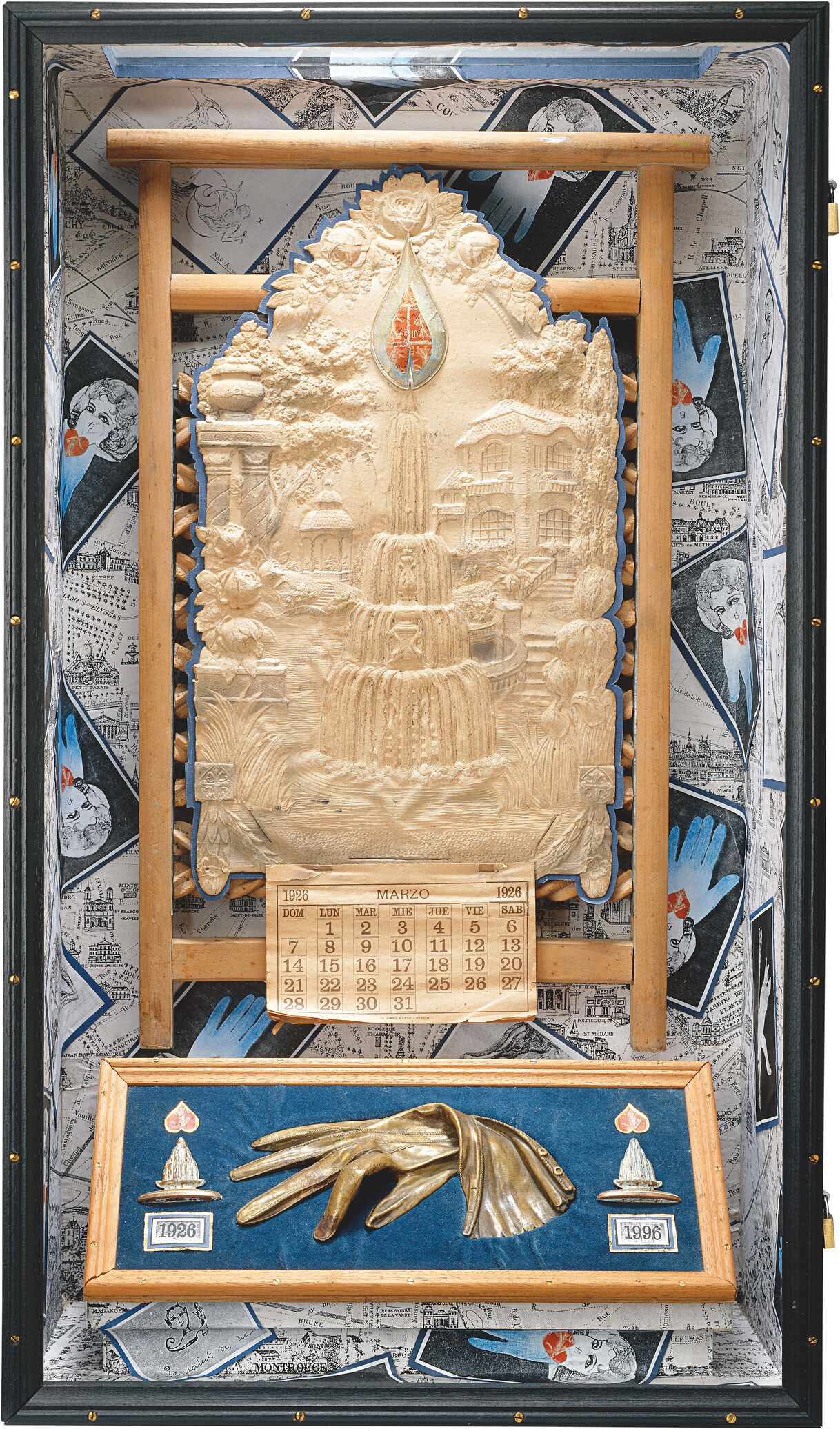

Glass’s assemblages are constructed from a vast repository of materials acquired over several decades. His approach to locating these are derived from the Surrealist found object, the chance find that is ostensibly capable of revealing desire and long sought after poetic truths.33 Discovering these sometimes allow Glass to complete a work that has lain dormant for decades; at other times, unearthed treasures instantly communicate with one another and suggest a new assemblage.34 The convergence of chance finds and Surrealism’s history is prominent in Sorprendente hallazgo (Chance find) FIG. 16, which was triggered by his flea market purchase of a bronze glove similar to the one Breton writes about in his autobiographical essay Nadja (1928). Glass soon came across further objects that spoke to dates and events in Nadja.35 Combining these trouvailles, he created an altar to one of Surrealism’s foundational texts and the woman, in reality named Léona Camille Ghislaine Delacourt, whose spirit infuses it. As such, Sorprendente hallazgo is a result of Glass’s transnational practice and his constant attention to the manifestations of chance finds and connections.

Arriving is departing

Glass’s long life of travel and migration resonates in his assemblages. His art frequently evokes journeying and navigation, laden with the poetic thrill of new experiences, but also tinged with the melancholy of displacement.36 As much is apparent in a suite of four boxes he made in 2016 on the theme of arriving in Paris FIG. 17 FIG. 18. When Glass moved from Canada to Paris in 1952, he arrived by boat and took up residence at the Le Sphinx hotel in Montparnasse. The building, once a famous brothel, housed students and artists and was located on the Boulevard Edgar Quinet, next to Gare Montparnasse. The view of the train station was familiar to Glass from Giorgio de Chirico’s 1916 painting The Melancholy of Departure (Tate, London).37 In these two assemblages he incorporates elements taken from reproductions of de Chirico’s painting, as well as its predecessor Gare Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure) (1914; Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1914; private collection) in order to sound out and crystallise his memories of migration, where excitement and expectation, melancholy and displacement, appear to have been equally strong. Alternately shrinking and magnifying details of de Chirico’s paintings, Glass places them in contact with each other as well as with found objects in an enigmatic treatment of the double feeling of departing at arrival.

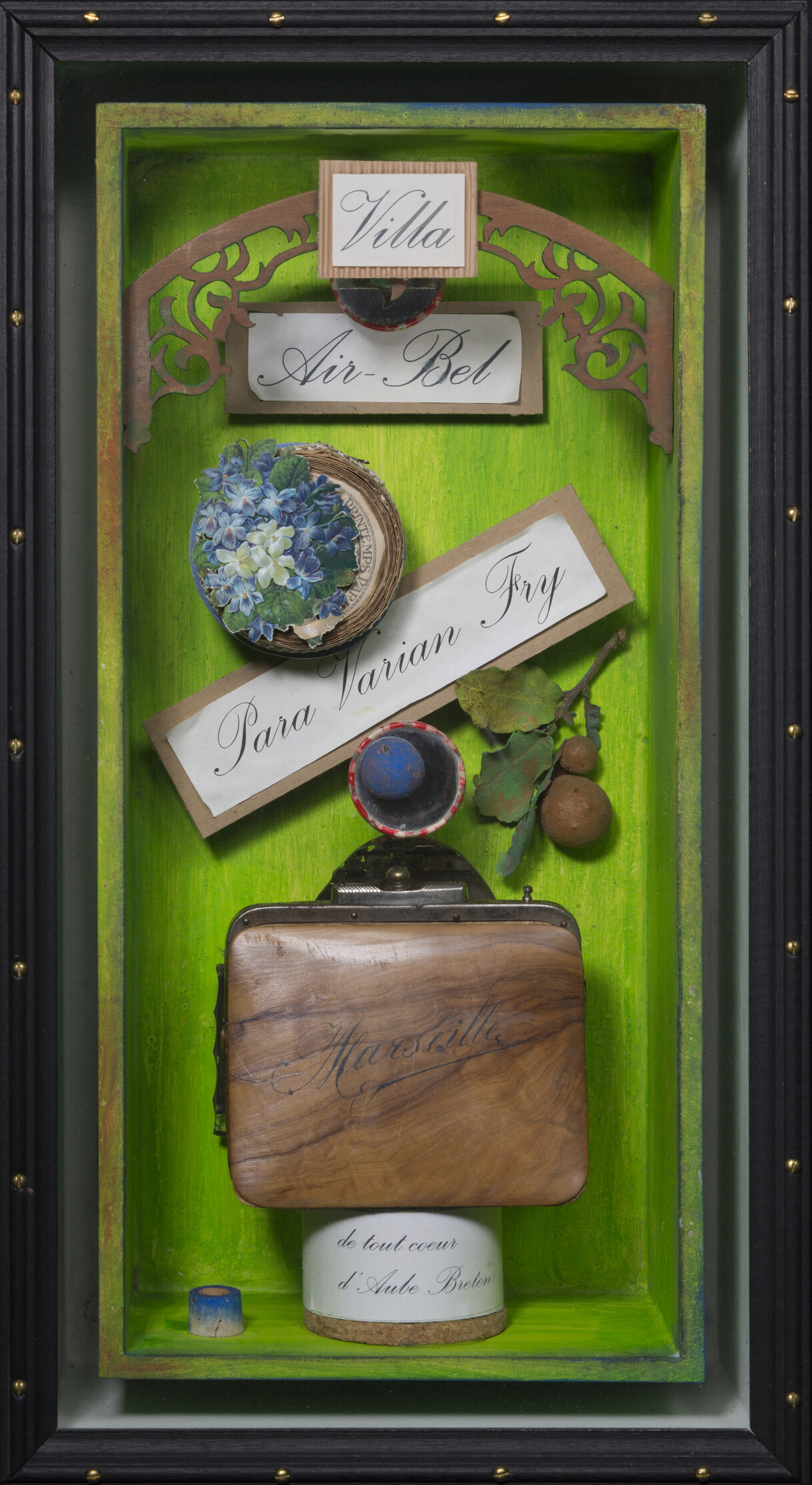

In a series of five boxes completed in late 2019, Glass turns his attention to an earlier, liminal historical moment when the spectre of forced migration loomed large over Europe. The series centres on the Villa Air-Bel in Marseille, where the young American Varian Fry spearheaded the Emergency Rescue Committee in helping German refugees and Jewish and leftist intellectuals escape Nazi-occupied France.38 Among those who awaited safe passage were several Surrealists, including Breton, his wife, Jacqueline Lamba, and their daughter, Aube. Since the 1950s Aube Breton-Elléouët has been one of Glass’s closest friends. The impetus for his Marseille-themed boxes was Breton-Elléouët’s gift of a miniature handbag made of wood with Marseille written on it, which she found in a flea market when visiting Marseille for an exhibition about Fry.39 In one work, the handbag rests upon a piece of cork wrapped in white paper with ‘de tout coeur d’Aube Breton’ written on it FIG. 19. A tilted sign reading ‘Para Varian Fry’ hovers over two further signs that proclaim ‘Villa’ and ‘Air-Bel’. The Spanish-language dedication to Fry is further echoed in details that play on Mexico in a double-sided box – the most prominent feature of which is a green parrot FIG. 20. A piece of paper advertises a new restaurant, ‘El perroquet’, in Mexico City; on top lie two yellow knobs bearing the initials AB and BP: André Breton and Benjamin Péret. Breton and his family travelled to the United States from Marseille, while Péret and his wife, the painter Remedios Varo, moved on to Mexico. In this series Glass conjures up a historical moment of dispersal and exile, while also quietly alluding to his own voluntary displacement from France to Mexico and the threads that kept him connected to Paris.

The direness of the disaster that was unfolding in 1941 is also potently conjured up in a box in which a disembodied green hand and a loop of barbed wire speak to the moment’s looming threat of imprisonment and its atmosphere of confinement FIG. 21. Underneath, a miniature radio evokes the impatient wait for news. Created during a moment of vast refugee streams, when the United States keeps immigrants in detention camps and children are separated from their parents, Glass’s Marseille suite digs tunnels through time. The boxes connect past and present in charged constellations, in which remnants of earlier moments speak to our current era in oblique yet immediate ways.

When the Second World War ended, many Surrealists returned to Europe from exile. As they sought to grapple with the disaster the world had undergone, the movement’s penchant for destruction now appeared obsolete. Breton proposed a new ascendant poetics of renewal and healing.40 Arguably, most of Glass’s assemblages are constructed according to a similar poetic logic, where darkness and despair are transmuted into new spirited arrangements. One of his Marseille boxes exudes a particularly strong atmosphere of renewal and the possibility of transformation FIG. 22. Its most prominent feature is a small ladder painted in the colours of the rainbow, next to which is mounted a rainbow-coloured pencil. Shavings from the pencil are attached to the ladder, as though to emphasise the healing potential of writing and drawing. Beneath the ladder is a light bulb that has been painted to look like a bird cage holding a pink bird. The words REGNE and BEAU bookend the work: regne beau, meaning beautiful reign, is a near-homophone for rainbow. The box suggests that possibilities of a transformative, ascendant escape from the present and the promise of a new era are poised to emerge from the dire time of refuge, migration and exile.

The poetics of displacement in the de Chirico and Marseille suites speak to Glass’s errant life. Although settled in Mexico for the better part of the past six decades, his memories of earlier places, friends and cultures are vibrantly present in his art. The German Romantic poet Novalis, one of Glass’s sources of visionary inspiration, has described a creative and spiritual dynamic of a similar kind as that which underlies much of Glass’s work.41 Novalis comments on the relation between inner turmoil and Witz (wit): ‘In peaceful souls there is no wit. Wit is the sign of a disturbed equilibrium: it is the result of this disturbance and the means of restoring it [. . .] The state of dissolution of all relations, despair or spiritual death, is terrifyingly witty’.42 In stark contrast to vernacular notions of wittiness, Witz is that which dissolves the world as we habitually experience it, but also that which reconstructs and reinvents it.43 The philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy comments that there was an ‘age [or] era of Witz’.44 In line with its folding of time, it is perhaps only appropriate that Glass’s art prompts us to recover the evasive concept of Witz. Glass’s Romantic Witz takes expression in assemblages that at one and the same time dissolve the world, reassemble it and transmute it. It renders his poetics of displacement into an ascendant assemblage practice.

Conclusion

The delight resulting from Glass’s Sorpendente hallazgo and chance discovery of a Mexican sugar skull in the early 1960s was the main impetus for his travel and eventual emigration to Mexico nearly sixty years ago. Yet this initial sensitivity to aspects of Mexican culture also developed into a key aspect of his assemblage process with the found object over the course of his life in Mexico City, where the artist’s daily openness to surprising finds has never ceased to be his fundamental mode of creation.

Traces of the material and visual culture of Mexico proliferate in Glass’s extensive œuvre and are in some cases woven into a transnational amalgam of French, Canadian and American sources and references. At other times these traces are poised in a splendid, solitary tribute to the land of his naturalised citizenship. Works such as Espuma de luna. Bautizo del nuevo día, with its looming scale at 140 centimetres high, pay homage to Mexican religious and handicraft traditions, even as they simultaneously evoke the history and legacy of Romanticism in a transcultural visual poem FIG. 23. A pristine cotton baptismal dress hovers over a painted landscape, communing with the stars and the night sky and symbolising the glistening halo and ‘foam’ of the moon as a new day rises. In the work of Alan Glass the found object paradoxically offers a path for potential discovery beyond the confines of identity, wherein the mundane or familiar finds new resonance in an intuitive encounter with the previously unknown. Glass’s emigration to Mexico over half a century ago has resulted in a lifetime of dynamically transnational assemblages, which at once pay homage to the cultural heritage of this nation and underscore the artist’s expatriate orientation.45