Petra Bauer and SCOT-PEP’s ‘Workers!’: renewing the aesthetics and politics of 1970s feminism

by Victoria Horne • November 2019 • Journal article

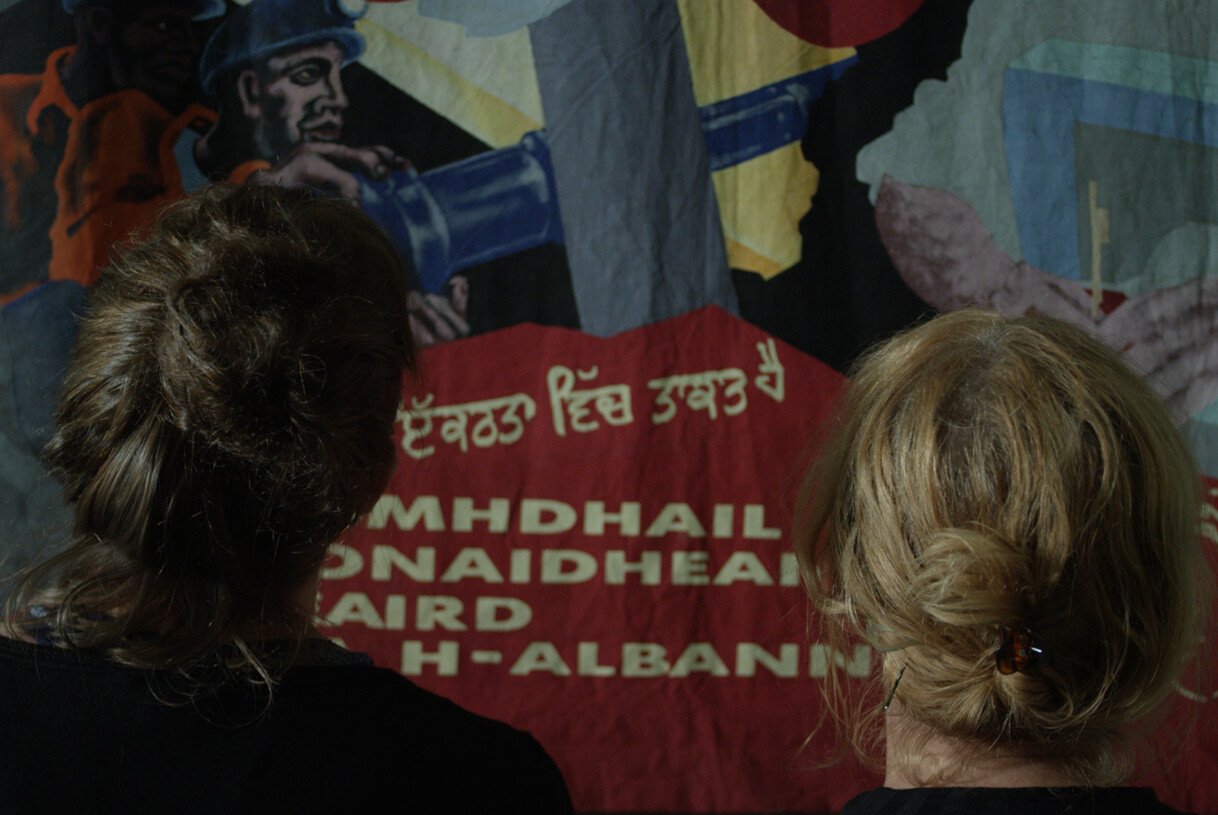

Workers! is a research project directed by Petra Bauer in collaboration with the sex worker-led charity SCOT-PEP and facilitated by Collective, an arts organisation in Edinburgh.1 SCOT-PEP was established in the late 1980s and the group continues to organise and campaign for the labour rights of sex workers, including the full decriminalisation of sex work in Scotland.2 Taking place between 2015 and 2019, the Workers! project resulted in a thirty-eight minute documentary film FIG. 1, a banner designed with the artist Fiona Jardine and an archive of resources including published articles, books and an hour of audio recordings with participants. The film insists on situating sex work within a general labour movement and in so doing endeavours to shift the discussion from a moral to a material ground. This emphasis on labour, as articulated by Molly Smith and Juno Mac, follows the approach of the International Campaign for Wages for Housework in the 1970s, which argued that ‘naming something as work is the crucial first step in refusing to do it – on your own terms’.3

The narrative structure of the film is straightforward: the camera follows a group of unnamed women as they appear to prepare a conference or corporate event over a single day in the Scottish Trade Union Congress building in Glasgow. The viewing experience is restrained yet intimate, as we listen to seemingly unscripted conversations about holidays, moving house, work, run-ins with the police or landlords, feminism and representation; all layered over protracted sequences of food preparation, cleaning and other household or organisational labours. Although this is a documentary about sex work, it quickly becomes apparent that the focus is on work rather than on sex.

The purpose of this article is not to dwell on the legal, ethical or philosophical entanglements of prostitution, but to explore the aesthetic and political strategies employed in the project. Workers! provides an intriguing example of visual-activist culture within contemporary art, in that the film-makers negotiate the challenge of documenting the politics of the sex-work labour struggle and producing an advocacy film, while retaining the anonymity of its socially stigmatised subjects. In order to achieve this, Bauer and SCOT-PEP returned to pivotal moments in the feminist archive, to the films, publications and debates that forged a cultural context for their work. This return reopens significant cultural inquiries associated with late twentieth-century feminism, including whether there are particular ways of making and distributing films as feminists, and if there is a feminist aesthetic.

The spectacle of feminist activism

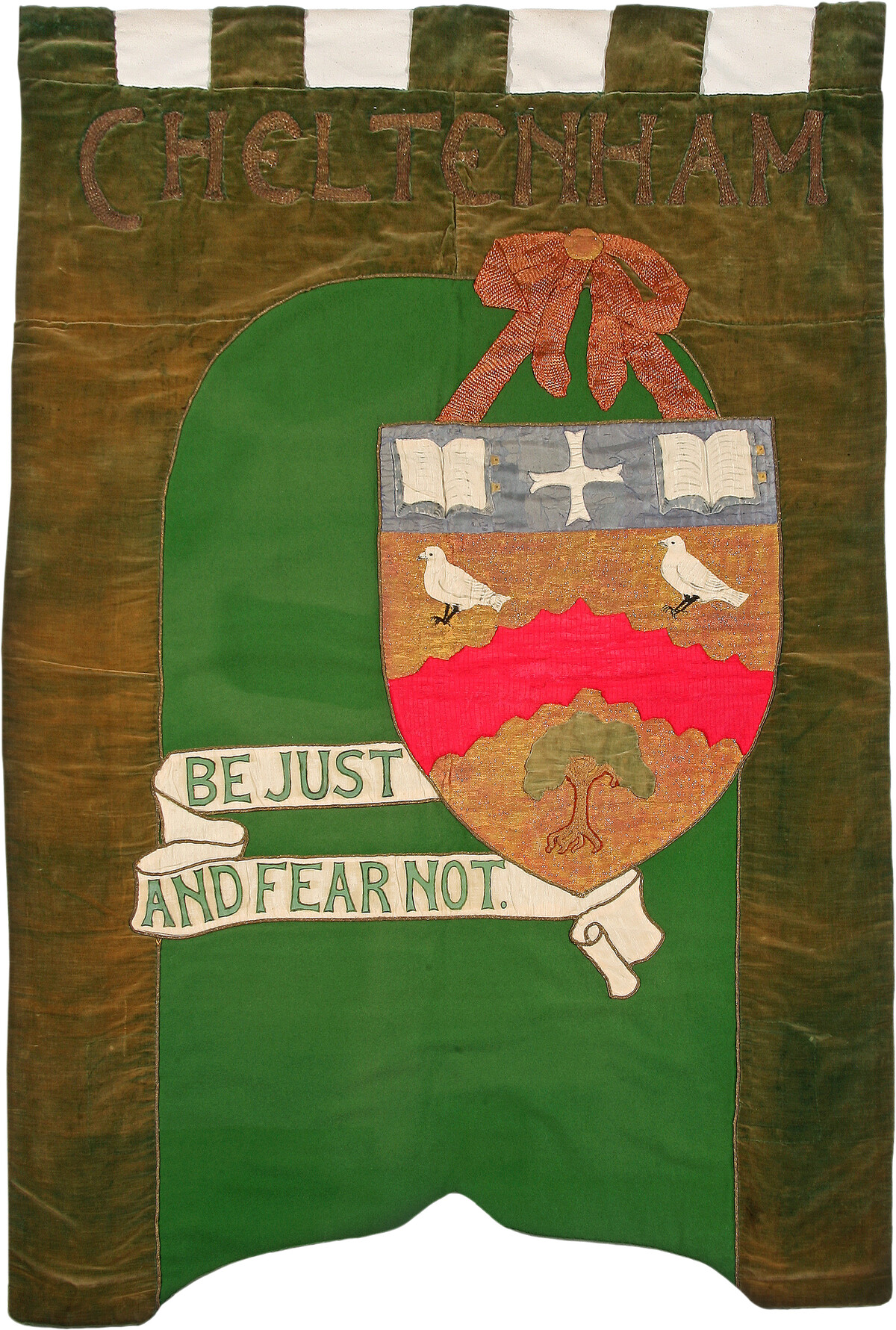

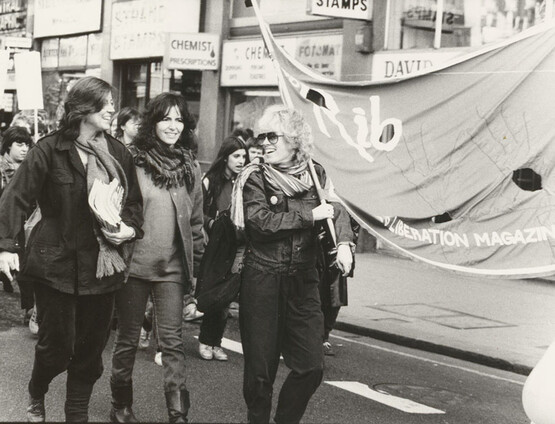

In her book The Spectacle of Woman: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign, 1907–14 (1987), Lisa Tickner characterises that activist moment in terms of spectacle and pageantry, describing how, for early twentieth-century feminists, visual strategies were crucial in their battle for political and social representation FIG. 2. Although they rarely engaged with the visual arts directly, suffragists strategically employed banners FIG. 3, postcards, fashion and large-scale public spectacle to stake a claim on what was a predominantly masculine political sphere.4 Across the intervening century spectacular mass protest has become an established means of expressing dissent. However, while some of the organising strategies endured, for some decades in the mid-twentieth century the women’s suffrage campaign faded in memory; it was considered ‘marginal to the interests of political historians’ and its visual history too ‘ephemeral’ or ‘political’ for the interests of art historians.5 This observation orientates us towards the ebbs and flows of activist history, indicating that the reason particular struggles move in and out of historical vision is always a question of power, as is the matter of which subjects are permitted to represent themselves.

The achievements of the women’s suffrage campaigns are now firmly lodged in the United Kingdom’s memory culture. Contemporary feminist scholarship is moreover markedly attentive to the means by which popular knowledge about the past is transmitted to the present. Red Chidgey has suggested that we are living through an era of ‘assemblage memory’, in which the political past is pieced together and mediated through works of art, blogs, festivals and protest imagery.6 Think, for instance, of protest participants wearing suffragette costumes and how these are employed to positively invoke traditions of disobedience and resistance. This affirmative cultural mode marks a clear (if sometimes limited) re-engagement with activist pasts, following years of what Angela McRobbie has described as a cultural politics of ‘postfeminist disarticulation’, in which previous feminist movements were repudiated as unfashionable and irrelevant to younger women’s lives.7 Resonating with this language of remediation or historicist assemblage, Bauer described her ambitions for Workers!:

We wanted to insert sex work into a historical labour movement, to rewrite that history. In a way, that is the political intention and the political potentiality of the film. It is something that has been done and cannot be undone. The labour movement has to consider it. And I feel proud that we did that.8

The film’s production was driven by the desire to register a marginalised form of labour publicly, to contextualise it historically and to situate it upon a broader landscape of feminised reproductive labour – that under-appreciated and under-compensated work of cooking, cleaning and caring that reproduces the labour force on a daily and generational basis. Workers! is therefore deliberately situated on a continuum with earlier moments of political organising, and its historical self-consciousness is very much a product of our current memorialising moment’s affirmative relationship to feminist-activist pasts.

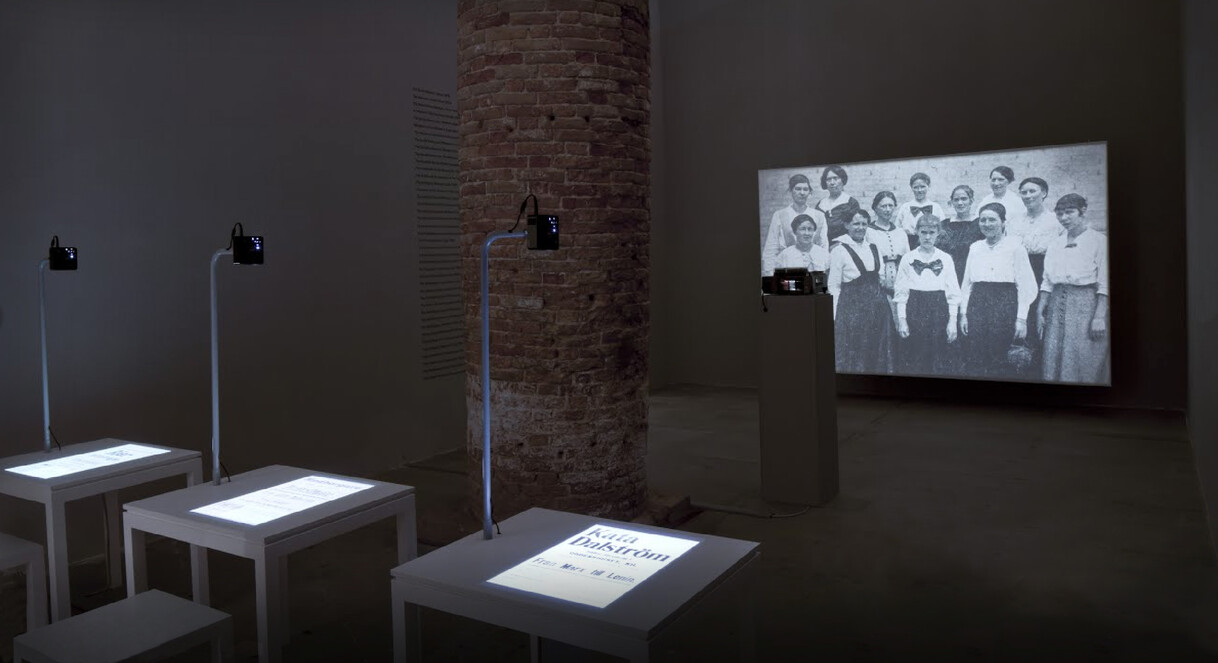

Bauer’s interest and engagement with early twentieth-century activisms can be observed across her career, although the historiographic impulse underpinning her contribution to the 2015 Venice Biennale is especially striking. A Morning Breeze FIG. 4 recovered documents and group photographs from the records of socialist women’s groups in Sweden between 1907 and 1920, exhibiting them within a pseudo-archival environment in which audiences inhabited the role of historian by interacting with digital slide projectors and archival materials. The cloth banner produced by SCOT-PEP, with its slogan ‘Rights. Safety. Justice’ FIG. 5, is a similarly evocative gesture towards the past. It recalls the industrious banner production of suffragists and trade unionists, although updated by its digital printing method and playful neon script announcing ‘Sex Workers’.

The activist L.A. Kauffmann has suggested that we can learn to ‘read’ protests through the signs people carry, and that both the production (professional or artisanal?) and message (individual or collectively driven?) reveal valuable information about the structural nature of the action.9 According to Tickner, suffrage banners were valued as ‘portable’, ‘decorative’ and ‘informative’, while women’s ‘collective banner-making’ evoked communal and creative ‘pleasures’ FIG. 6.10 Echoing these pleasures, Bauer’s film shows SCOT-PEP members comfortably chatting while cutting, pasting and experimenting with banner designs FIG. 7. The banner thus constitutes a reinvention of a historic form in both materials and meaning: it blends old and new media, communicates a radical message and affiliates Workers! with activist organising strategies so strongly associated with the previous century.11

The film is set at the Scottish Trade Union Congress (STUC) headquarters, a converted Victorian schoolhouse in Glasgow’s West End. SCOT-PEP’s one-day occupation of this imposing red-brick building is a powerfully symbolic gesture in the struggle to register prostitution as work.12 Tracking a figure as she enters the building, Bauer’s camera then roams the empty interior, scanning tattered campaign posters about 'performance management' or asking 'does your boss keep your tips?'. The beige walls are decorated with banners and photographs commemorating earlier battles and stencilled with poetry valorising collective organisation. Yet these established cultural celebrations of labour are off-limits to SCOT-PEP because its members are seen as ‘the wrong kind of worker’.13 According to the film’s discussions, members had been refused permission to use the building for an earlier event and – fuelling their exasperation – when arranging a rally to protest the STUC’s decision, the group’s posters were deemed ‘too contentious’ by most print shops in the area. As one voice observes, the message was clear: ‘You can’t meet here. You can’t have the venue. But you also can’t have the signs to protest that!’

The location, union imagery and narration hint at the complex political and representational field within which Workers! is attempting to intervene. Tickner has noted how, for the suffragists a century ago, the labour movement ‘offered an important example of an oppositional group engaged in the invention of its own symbolic tradition’.14 Workers! stages a similarly tactical engagement with these traditions, although the way that the power of contemporary unions is wavering is left curiously unexplored. In 2018, for instance, the STUC announced its decision to sell its impressive building to private developers, who plan to convert it to student accommodation.15 Against these shifting sands of urban politics, planning and capital, SCOT-PEP’s occupation of this site is especially meaningful. The film-makers’ optimistic engagement with certain traditions of the labour movement ensure that the movement remains a source of inspiration, even as its shortcomings are acknowledged. Thus in an extended segment of the film we watch three women methodically remove framed photographs from the walls and replace them with tacked photographs of sex-worker meetings, rallies, and protest signs FIG. 8; the act constituting a symbolic, if temporary, intervention into a history that has sought to exclude them.

Renewing aesthetic strategies

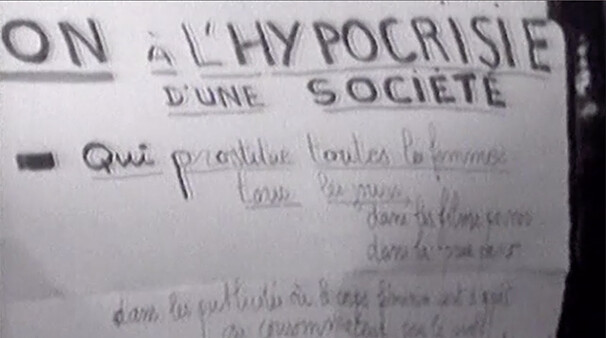

As well as situating Workers! in relation to the social history of trade union organising, and working in a way that is not dissimilar to the second-wave’s repossession of suffragist histories, the film’s formal strategies knowingly echo the conceptual and aesthetic tactics developed by the feminist movement of the 1970s. The wider research project included regular workshops on key films, articles and books about sex work, art work and housework. A selection of these materials is gathered in a research folio exhibited alongside the film which acts as a bibliography of references. Two films stand out as especially pivotal influences. Carole Roussopoulos’s documentary Les Prostituées De Lyon Parlent (The Prostitutes of Lyon Speak Out; 1975) is a short film made in the context of a sex workers’ occupation of a church in Lyon in protest against police brutality and lethal working conditions FIG. 9. Roussolpoulos’s trust in the engaging eloquence of her subjects is evident in the lightly edited, talking-head format of the film, through which its core arguments are unfolded. Its influence is decisively felt in the informal conversational style of Workers!, as well as its succinct length, its educational mission and the fact that the film was made with rather than about sex workers.

In Workers! faces are, for the most part, hidden from the viewer (something also true of many of the women in Roussopoulos’s film). Participant anonymity is secured through imaginative framing as we watch activities from unusual angles – from behind or above, reflected in mirrors and puddles – or are shown slices of bodies and torsos and legs as they walk past a low-level camera. Bauer’s lens most often focuses on hands busy at work. We watch hands decorated with pointed, peach-painted or sparkly nails, as they stack chairs, open blinds, wipe tables, wash fruit, clean dishes and sew banners. Bauer refers to these acts as ‘gestures of feminine reproductive labour’ and the close, compressed shots draw the viewer into these dully familiar actions.16 The conversational dialogue is layered over these sequences in what Lauren Houlton describes as ‘a form of collaging’, which persistently links ‘sex work to reproductive labour’.17 This collage technique formally embeds the conversations relating to prostitution in the material realities of care and maintenance that sustain both individuals and social movements over time.

These durational passages of household and organisational labour resonate with another of the film’s major influences, Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman: 23 quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). This almost four-hour film scrupulously tracks a widowed mother over three days in her apartment as she follows a measured regime of cooking, cleaning, childcare and sex work. Akerman, as Patricia Sequeira Brás writes, ‘deploy[s] cinematic time to allude to the constant and ongoing process of reproductive labour itself’.18 Duration is therefore experienced in not only the real-time depiction of reproductive activities, but in the film’s poetic registering of prolonged, repetitious actions that smudge together in an almost indistinguishable haze FIG. 10. Although far shorter in length, Workers! echoes the cinematic temporality of Akerman’s film in its sequences of unrelenting reproductive and organisational labour. This is work that never ends, yet leaves nothing permanent in its wake, as clean dishes become dirty and sated mouths become hungry again FIG. 11.

Both Workers! and Jeanne Dielman almost entirely avoid the direct representation of sex (except in the latter’s dramatic ending, which shows Dielman with one of her clients). This may be a logical response to prostitution’s burdened representation to the challenge of representing sexuality beyond spectacle but it also acknowledges the extent to which women’s housework and sex work are interwoven under capitalist social conditions. This is not to say they are equivalent, but Brás argues that domestic work and sex work in Jeanne Dielman ‘are different only in form, because housework and prostitution are the two sides of the same reproductive labour’.19 Similarly, the narrative and aesthetic composition of Workers! invites its audience to at least consider how the conditions od sex work connect with broader feminist and workers’ struggles. In its careful ‘collaging’ of sex work, domestic work and art work, Workers! implies that the social, economic and psychic structures shaping these modes of work are the same, even as the labour practices and effects are distinctive.

As Federici writes, sexuality under capitalism is work, although ‘we know that this [sex] is a parenthesis which the rest of the day or the week will deny’.20 Thus she contends it is not a natural experience, joyfully distinct from all other socialised conditions of existence, but is woven into the fabric of our working lives. Reflecting this parenthetical structure, in Akerman’s drama sex occurs mainly in filmic ellipses, while Workers! withholds its direct representation altogether. This is somewhat contradictory: by refusing to represent this labour it is underlined as distinctive or singular and the tactic perversely fuels interest by frustrating the viewer’s prurient desire for more information. One ambivalent reviewer even suggested that sex (work) is ‘the elephant in the room’.21

This discomfort or friction is essential to understanding the film’s position, the representational gap pointing to sex work’s entangled nexus of waged and unwaged, formal and informal labour, and economic and sexual autonomy. The film-makers do not locate the immediate problems faced by sex workers in the labour itself, but in the social conditions that criminalise and drive it underground. Consequently this is not the site that needs to be represented. Moreover, in Workers! the absent time of this unrepresented labour (sex work) is thrown sharply into relief against the banal drudgery of care work and organisational labour. This reminds viewers that the issue of time is one frequently raised by sex workers as a motivating factor, given the low-paid and time-intensive nature of other jobs often available. Understanding and improving the realities of sex work consequently requires not moral reasoning, but comprehending its connection to wider, often dismal and coercive, economic conditions.

Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman is notable for its total absence of reverse shots, a framing technique that Bauer borrows to avoid showing the film’s subjects directly and to interrupt the documentary camera’s naturalised window onto its subjects. One scene in particular expresses the film’s ambivalent attitude towards direct visual representation FIG. 12. It is strikingly composed: two women huddle under a red umbrella with another resting between their legs, the intimate tableau reflected in a glassy puddle on the tarmac. The red umbrella has been the international symbol of sex workers since the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001, where sex workers paraded through the city’s narrow streets, the bright red canopies at once making visible and shielding their occupants.22 It is apposite that this iconography emerged at an art fair, given the historic entanglements of visual art, sexuality and spectacle. For while the realities of sex work may be under-represented in trade union-led labour struggles, prostitution is profoundly overdetermined in cultural representation as the ultimate ‘fallen woman’. Lynda Nead has written at length about the aestheticisation and popularisation of this figure in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, suggesting that:

the prostitute was a cipher for a certain version of modernity, which emphasised the transitory nature of modern life, the loss of permanent values and the transformation of emotional relationships into economic exchange. It was romantic and melancholy, and it was a fantasy.23

That she was writing critically about a 2015 exhibition on the theme of prostitution evidences that such fantasies are not confined to history.

The two women sheltered beneath the red umbrella reproach feminists for taking a paternalistic position and not listening to sex workers or treating them as experts in their own lives; and they touch upon ideology, stating that ‘emotion shouldn’t have a place in policy’. Most pertinently, they argue that female prostitutes serve a ‘symbolic function’ and the conversation too often gets stuck in a representational space. ‘What does it mean’, one voice asks, ‘that women sell sex? What do sex workers symbolise?’ Their conversation implies that focusing on these ideologically driven questions diverts feminist energy from addressing immediate material concerns, including how to improve safety and ensure economic stability for sex workers. This critical position, alongside the refusal to depict or discuss sex work directly, generates an uncertainty. Workers! is not a campaign film with a straightforward message; rather, it is a discussion- and research-led film exploring sex work and its cultural representation. Is this not, therefore, precisely the space to reflect on those ideological and symbolic questions? To think critically, for example, of the power dynamics that persistently allow (predominantly) men to sexually exploit women.

Bauer has reflected on the complexities of working with this stigmatised group, suggesting that its members are ‘about surviving economically and socially, and so there’s a lot of vulnerability and precariousness and problems in being visible’.24 Elsewhere she elaborated:

As a film-maker, this challenged me. How can you show bodies at work, and bodies organising, without showing faces? But, more importantly, how do you address the politics of SCOT-PEP without making anyone visible? How can you even make politics without being visible? 25

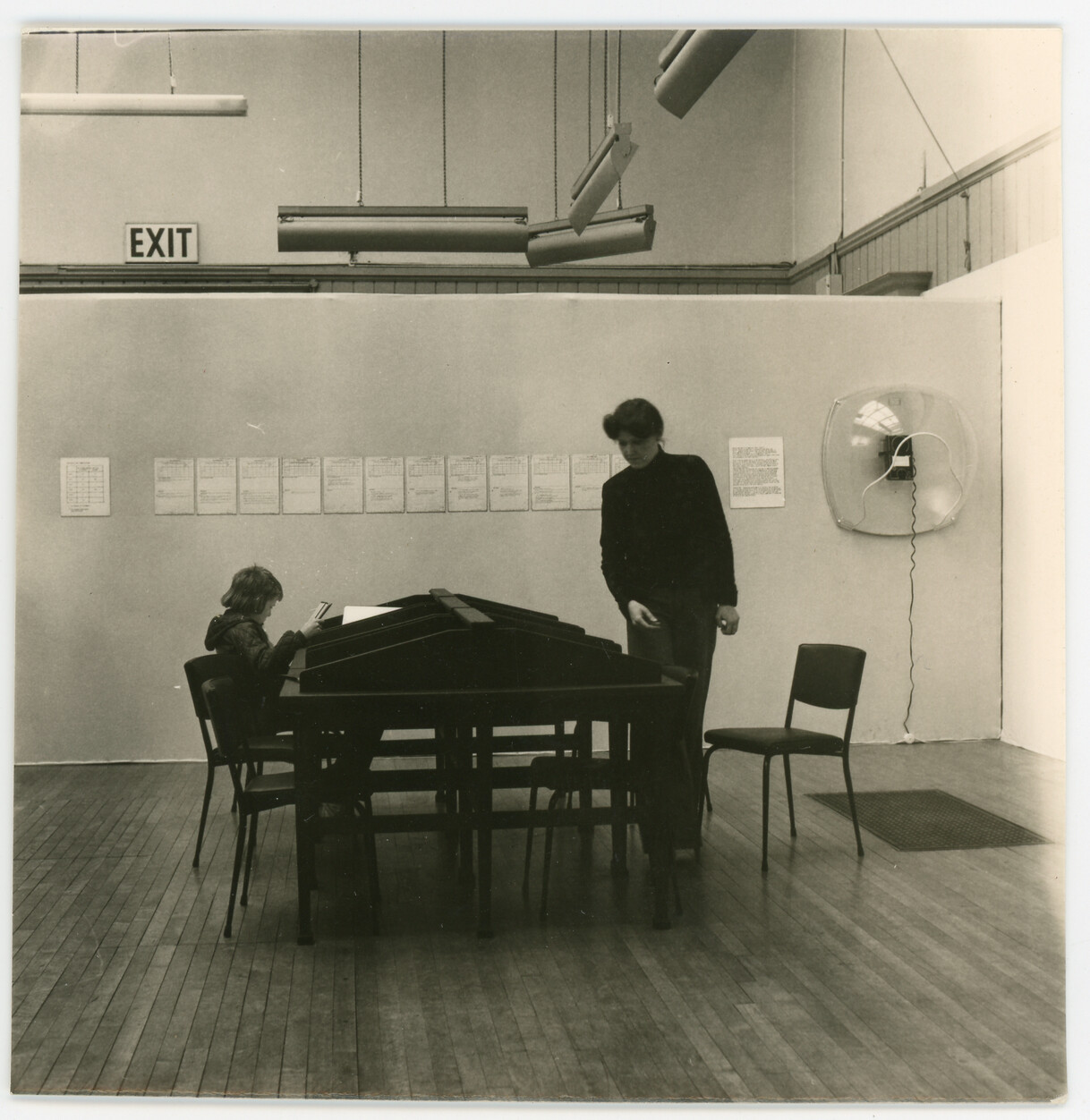

In seeking to answer these questions Bauer looked towards feminist aesthetic debates of the 1970s and 1980s, at which time theorists and artists developed alternative, conceptual systems of representation in resistance to the compromised traditions of the visual. For instance, Women and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry (1975) FIG. 13, an exhibition led by Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt and Mary Kelly, abstained from direct representation in favour of quasi-sociological, diaristic and tape-recorded traces of its subjects, box-factory labourers in London.26 The documentation draws attention to the disparate pay and promotional opportunities between men and women at the factory, and how these were affected by the 1970 Equal Pay Act. Women and Work introduced second-wave feminist politics to conceptualism’s cool iconophobia and, although its formal aesthetics are now fairly ubiquitous across contemporary art, the thematic correspondences with Workers! lend weight to this resemblance FIG. 14. The gallery-library display of Workers!, featuring headsets, box files and documents FIG. 15, formally echoes Women and Work’s archival installation environment, while the focus on how women’s labour struggles are inseparable from the broader realm of non-paid work extends the political and conceptual focus.

As the camera follows SCOT-PEP cleaning and preparing the building’s familiar internal spaces, the film recalls another documentary, also set within featureless, bureaucratic office buildings and following the movements of rarely seen female workers. Nightcleaners, produced by the Berwick Street Film Collective, charted efforts to unionise the women who cleaned London’s office blocks at night FIG. 16.27 In 1971–72 the collective spent eighteen months with union organisers and activists, filming the cleaners at work, before a protracted period of editing the film, which was not completed until 1975. Although not included in the Workers! research folio, the film is a vital touchstone for Bauer.28 Most obviously these are both documentaries about the organisation of a feminised workforce. Nightcleaners’ themes of femininity, labour, urban experience and migration resonate with that of Workers! and, as Sheila Rowbotham writes of the former, in a comment equally applicable to the latter, it ‘offers a rare insight into the experiences of a group of women who even within the working class have little visibility as historical subjects’.29

Both films strive to generate thinking on the critical potential of the medium to contribute to activism, and to interrupt the conventions of representing work and working-class women in that medium. Nightcleaners, however, drew vociferous criticism for what was understood as the incommensurability of its activist subject and avant-garde medium, and as Siona Wilson describes it, ‘many feminist activists harshly rejected it because it failed to deliver a straightforward campaign message: the intersections of race, class and gender remained intractably dissonant’.30 A similar charge could be levelled at Workers!, and one might ask whether Bauer’s practice of working with activist groups (her previous film Sisters! was made in collaboration with the Southall Black Sisters, who organise against domestic and gender-related violence in South London)31 serves to appropriate their energies for a rapacious art world. What does it mean that this document of SCOT-PEP’s struggle has been produced for a gallery environment, rather than – as with Roussopoulos’s film, for example – for the streets and spaces in which those struggles materialised?32 The producer Frances Stacey points out, however, that the partnership is ‘mutually appropriative’ as SCOT-PEP continues to work with these materials and to distribute the film in contexts beyond its artistic origins.33

Nightcleaners epitomises the avant-garde engagement in the 1970s with deconstructive film theory, which was loosely derived from Bertolt Brecht via the journal Screen. Its experimental strategies included disruptive techniques such as the insertion of black leader tape,34 inconsistent voiceovers and sudden shifts in perspective. Brechtian influenced cinema of the period sought to merge pedagogy with activism via distancing aesthetic tactics that interrupted the representational and narrative realism of film, thus emotionally and intellectually provoking its audiences into action (at least in theory). Although the framing and sound editing of Workers! is far less aggressive than Nightcleaners, its unusual framing and refusal to clearly display its subjects generates a discomfiting sense of peering in; one is always aware of watching a film. The scenes are smoothly edited, inviting identification with its subjects as we watch the women complete their quotidian organisational tasks in the compressed spaces of the screen. Workers! does not therefore seek to suspend visual and narrative pleasure but embraces a Brechtian definition of activist film that involves ‘both entertainment and the pleasure of making new sense of the world’.35

Disseminating Workers!

The contexts and infrastructures for encountering feminist-activist films have changed considerably since 1975, when the works of Roussopoulos, Akerman and Berwick Street Film Collective were first circulated. Workers! is, however, inconceivable without the theoretical and aesthetic strategies established by feminist documentary and conceptual practices of that period. The film self-consciously enacts these associations for reasons practical (in order to avoid the direct representation of stigmatised subjects), political (to advocate for workers’ rights) and aesthetic (to assert the renewed necessity of political film-making in face of a perceived crisis in the organisation of paid and unpaid labour).36

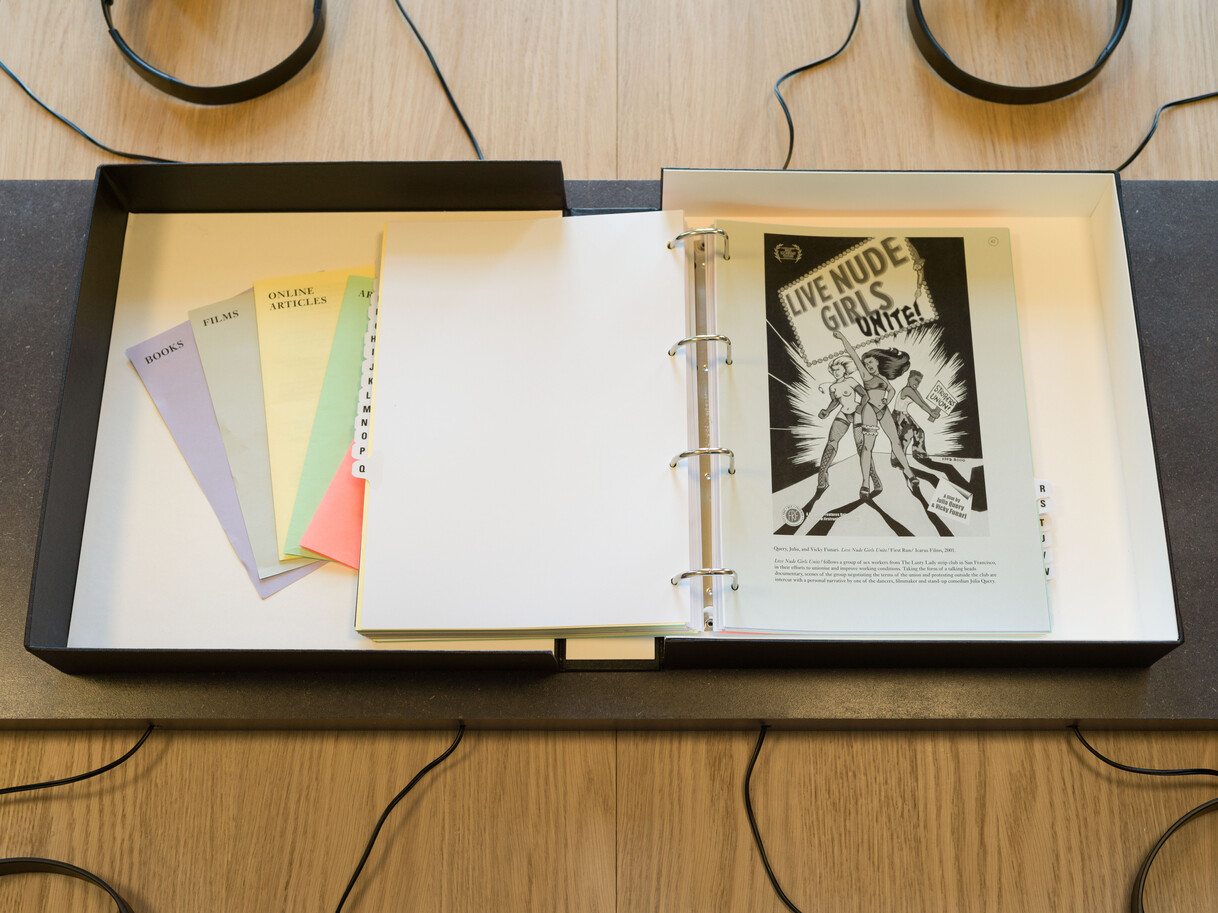

In addition to the gallery exhibition at Collective and public screenings of the film, the University of Edinburgh has acquired the film, banner and research folio for its Contemporary Art Research Collection.37 This acquisition – despite its relatively privileged and limited audience – fulfils the film’s pedagogical ambitions and satisfies the Brechtian belief that political film must comprise a learning situation.38 The project’s research folio FIG. 17, meanwhile, is designed ‘with the intention to be used by researchers as a starting point for future research on feminist practices and sex work politics’. Thus the project is intended as a dynamic activation of ideas rather than an artefact to be archived and consumed.

Nightcleaners, as Wilson puts it, continuously reminds viewers of the ‘labour on both sides of the camera’.39 By refusing to conceal the filmic labour and foregrounding the editorial cuts with black-tape interruptions, it generates critical reflection on the film’s representation of labour, union organising and processes of signification. Workers! adapts such tactics but does something conceptually distinctive by exhibiting the research processes that went into producing the film; documenting the workshops, readings and taped conversations between participants. In line with contemporary socially engaged art practices and the ‘artist-as-researcher’ model,40 the library installation and research folio highlight the intellectual labour underpinning the project, as well as generating multiple points of entry for viewers. Workers!, as the title suggests, is thus ultimately a project about many different forms of work and the value each is accorded – sex work, the reproductive work of labour organising, art work, research and educational work. It is also about the ideological work that culture does in obscuring the realities of sex work and misdirecting the conversation.

The suite of referenced films – Les Prostituées De Lyon Parlent, Jeanne Dielman and Nightcleaners – were all shown in 1975 as part of a wider social and cultural context that included deindustrialisation, widespread strikes, economic uncertainty and a thriving women’s liberation movement. Today we are witnessing a further reorganisation of work, as the characteristics of feminised care labour – precarity, vulnerability, poor wages, long and inconsistent hours – creep into all areas of the workforce. Consequently, the Workers! project suggests that the activist orientation of 1970s socialist-feminist art is strikingly, if depressingly, germane.

Returning to Tickner’s recovery of suffragist pageantry, spectacle and activism in the context of second-wave feminism; as one reviewer suggested, ‘the book could not have been written until now [when] quite self-consciously, contemporary feminism “entered the battlefield of representations”’.41 This led to ‘the production of tools appropriate to re-read the suffrage campaigns, so that they cease to be a purely historical, nostalgically irrelevant past and become a vivid and complex moment of our present’. Given the recursive nature of contemporary feminism, with its memorialising and affirmative logics, Workers! is clearly an attempt to forge a relationship to earlier activist moments that goes beyond nostalgia. Workers! (to mirror those observations on Tickner) could not have been made until this period of renewed labour and sexual politics, and the project endeavours to equip its audience with tools to re-examine the labour politics of 1970s feminism and to instructively make use of its knowledge in face of present challenges.

Workers! lays bare the reasons for SCOT-PEP’s collective struggle and invites solidarity by offering an unremarkable yet humane portrait of its subjects in their everyday lives. The film concludes memorably with a shift, which dramatically stages the displacement of individual identity in favour of an anonymised, collective one. Demonstrating a standard privacy tactic among sex workers and sex-worker allies, Workers! ends with the camera’s silent scan of women’s bodies and – for the first time – recognisable faces, although in this crowd there is continued anonymity, and strength, in collective visibility.42

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Vered Maimon and Siona Wilson for inviting me to present an early version of this article at the conference ‘Activist Images and the Dissemination of Dissent’ at Tel Aviv University, 11th–13th June 2019.