Patterns and Pictures: strategies of appropriation, 1975–85

by Jenni Sorkin • May 2019 • Journal article

In 1976 the critic and painter Jeff Perrone wrote that ‘Decoration becomes decontextualized by virtue of its being borrowed’.1 To decontexualise is to remove an image, an object or a pattern from its original context, rendering it a useable symbol through appropriation: the image is borrowed in order to be deconstructed. The resultant work of art undermines the social codes and assumptions of the original image as it was reproduced in its primary mass media and advertising context, or within the spaces of museums. Subsequently, this new, altered work challenges prejudicial collection practices that have habitually overlooked racial, gendered and non-Western histories.

Appropriation became a central strategy of artmaking in New York during the 1970s and 1980s, harnessed by two distinct groups of artists working in the city: the Pattern and Decoration movement (P&D) and what has come be known as the Pictures generation. The feminist-inflected Pattern and Decoration movement, whose core artists included Cynthia Carlson, Valerie Jaudon, Joyce Kozloff, Robert Kushner, Kim MacConnel, Dee Schapiro, Miriam Shapiro and Robert Zakanitch embraced intensive patterning and ornamentation in their paintings, collages and large-scale installations as a means of disrupting received histories of abstraction, high art and good taste. They engaged in an ongoing critique of what constituted the definition of ‘minor’ or ‘secondary’ in relation to the patterns, compositions and source materials they used in their work. The second, better-known group (here referred to as simply ‘Pictures’) takes its name from Douglas Crimp’s generative exhibition of the same title at Artists Space, New York, in 1977 (see catalogue below).2 Also known by the terms Appropriation movement or Image art, its artists include Gretchen Bender, Sarah Charlesworth, Silvia Kolbowski, Barbara Kruger, Sherrie Levine, Louise Lawler and Martha Rosler. These artists assimilated or copied mass-media text and imagery, producing works in text-based collage, serial photography and installations of found images or objects.

This essay will examine the points of intersection between the distinctive appropriative gestures of P&D and Pictures. Both movements were concerned with power structures. Reacting against the masculine imperative and phallocentricism of Abstract Expressionism, P&D sought to address the overt biases in the art world against decorative aesthetics – a critique of value – whereas Pictures was most interested in putting forward a critique of power, using lens- and graphic-based media. As sister movements, both harnessed cultural appropriation to make strong cases for the ways in which images and ideas are borrowed, culled and circulated. For both groups, this stemmed from a rejection of authorship.

Sister, we might say, also implies sisterhood – a community mainly of women that plays out in extremely complex ways. Although both movements involved committed feminists, P&D artists used feminism as a primary strategy, engaging in an active reclamation of women’s work, producing paintings and installations that directly referenced textile-based production, such as quilting, sewing and mending, whereas the Pictures group gestured towards gender politics through a dense repertory of media-inflected images, reprising and reworking problematic depictions of women. The assumption has been that P&D historicised, while Pictures theorised, presuming the latter to be somehow smarter, when, in fact, P&D was just as savvy.

A re-evaluation of P&D is especially timely, as it has resurfaced through a convergence of four exhibitions: Pattern and Decoration: Ornament as Promise, shown in 2018 at the Ludwig Forum in Aachen and currently at mumok in Vienna FIG. 1 FIG. 2, which will travel to the Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest in October 2019;3 Pattern, Decoration & Crime, on show at MAMCO, Geneva, earlier this year;4 Less is a Bore: Maximalist Art & Design, which will open at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, in June 2019; and, lastly, With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–85, which will open at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), in October 2019.5 These four shows exemplify the trend of museum-based curators mining the recent past as a means of seeking out overlooked or lesser-known historical precedents spearheaded by women and people of colour.

Before this flurry, the last major show devoted to P&D was held more than ten years ago at the Hudson River Museum, New York. Curated by Anne Swartz, Pattern and Decoration: An Ideal Vision in American Art, 1975–1985 cemented the movement as one linked to a sense of national American identity.6 In a review of the exhibition in The New York Times, Holland Cotter proclaimed P&D to be ‘the last genuine art movement of the 20th century, which was also the first and only movement of the postmodern era’.7

The feminist angle of the movement was borne in part of frustration with the dominance of macho-inflected Minimalism. For example, the spare installation works of Fred Sandback (1943–2003) use craft yarn to delineate sculptural space, while sidestepping the gendered cultural associations of fibre-based practices despite the material presence of a utilitarian textile. Historically, women artists have not been able to avoid the domestic or craft associations regarding their material concerns. Sandback’s floor-to-ceiling red yarn columns FIG. 3, one of seven installations commissioned for the New York alternative art space P.S. 1 in 1978, were highly formal works made during the last gasp of Minimalism, when new forms of content-rich practice were taking firm hold in New York’s alternative spaces.8 As the critic Carrie Rickey noted in 1980, ‘Minimalism was ready to tumble, and women were there to push’.9

1977–78: Pictures and Patterns

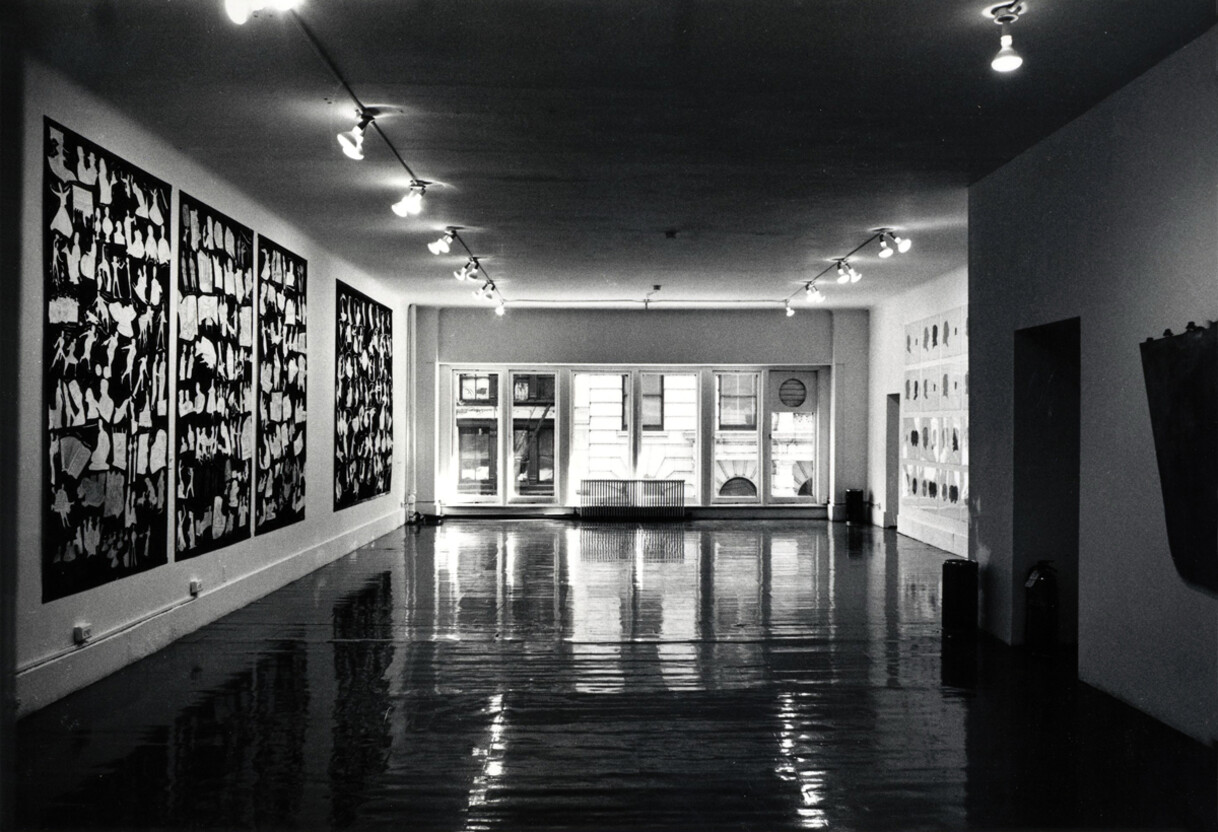

Within the space of a year, two exhibitions opened in quick succession that established the movements of Pictures and P&D. Crimp’s Pictures FIG. 4 opened in September 1977, bringing together the work of artists who engaged in appropriation tactics such as serial repetition in photography, video and print. Although only five artists were included – Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Levine, Robert Longo and Philip Smith – the term ‘Pictures’ is used generally, and in this essay, to define an expanded list that includes others such as Lawler, Charlesworth and Rosler.10 Moreover, recent scholarship has expanded the range of Pictures practitioners to include an even larger pool of lens-based feminist artists, adding those working primarily on the West Coast, such as Lynn Hershman.11

Opening just two months later, Pattern Painting, curated by the poet and critic John Perreault at P.S. 1, showcased P&D in the moment it was unfolding. With contributions from twenty-six artists, including Carlson, Kozloff, Kushner and MacConnel, Perreault was charting a tendency he called ‘The New Decorativeness’, which sought to eradicate what he regarded as the taboo practice of decoration. Simultaneously, he published a treatise titled ‘Issues in Pattern Painting’. His opening sentence affirms the artists’ commitment to feminism and historicism, declaring that ‘Pattern Painting is non-minimalist,non-sexist, historically conscious, sensuous, romantic, rational, decorative’.12

Perreault’s manifesto heralds a new form of painting that strikes at the heart of both Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. He overhauls Greenberg’s theory of ‘all-over painting’, according to which the work is equally balanced with no top nor bottom, by applying it to all-over patterning – lattices, arabesques, nets, geometric, florals – a populist embrace of all the cultures of the world at once, without introduction or specialised language. Intricate and repetitive geometric form was part of what Perreault described as a ‘universal decorative device’.13

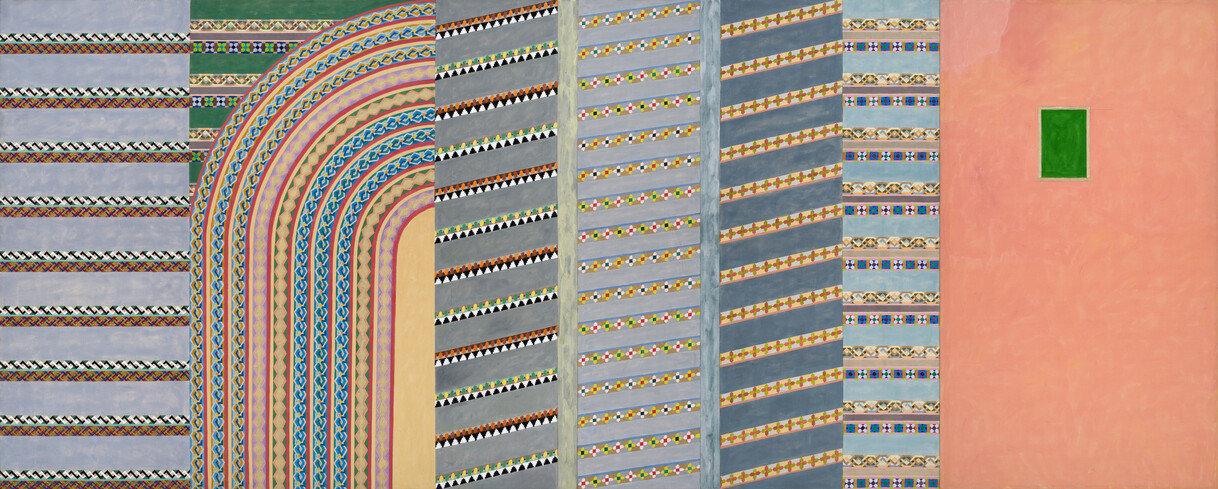

Not without complications, P&D’s collective appropriations constitute a purposeful ransacking of largely non-Western textiles, architecture, ceramics and beadwork. With ornament itself as the primary content, the decorative is redirected as simultaneously assertive, pleasurable and thoughtful, for example in Valerie Jaudon’s paintings of tight, interlocking shapes that derive from Islamic arabesque FIG. 5. Yet P&D was also a form of primitivism. It borrowed heavily from craft, folk and decorative arts traditions associated largely with Western women (quilting, piecework, salvage) and non-Western global textile practices (Japanese kimonos, Ottoman metal-ground silks and embellished beadwork).

P&D also coincided with the tail-end of the 1960s folk arts revival, a resurgence that had popularised vernacular traditions in a wide range of formats, from banjo music and quilts to the prevalence of teenagers in embroidered jeans and peasant blouses. In 1967, for example, Life magazine published an extended series of articles grouped under the cover title ‘Return of the Redman’, which tracked the burgeoning youth culture’s wholesale appropriation of Native American cultural traditions, entirely devoid of history: ‘In their reclaimed hunting grounds, hippies try earnestly to achieve authenticity. In Millbook NY, they live in teepees, in Sante Fe in hogans, and in Big Sur in tents [. . .] In cities, hippies have organized themselves into tribes’.14 Taken together, P&D’s intersections with the folk arts revival touched upon the zeitgeist of the era, or what Edward Said termed ‘imaginative geography’, the boundaries in the mind that make conscious and unconscious ethnic and racial distinctions, furthered by notions of distance, intrusion and the cultivation of the familiar as near and alterity as ‘far away’.15

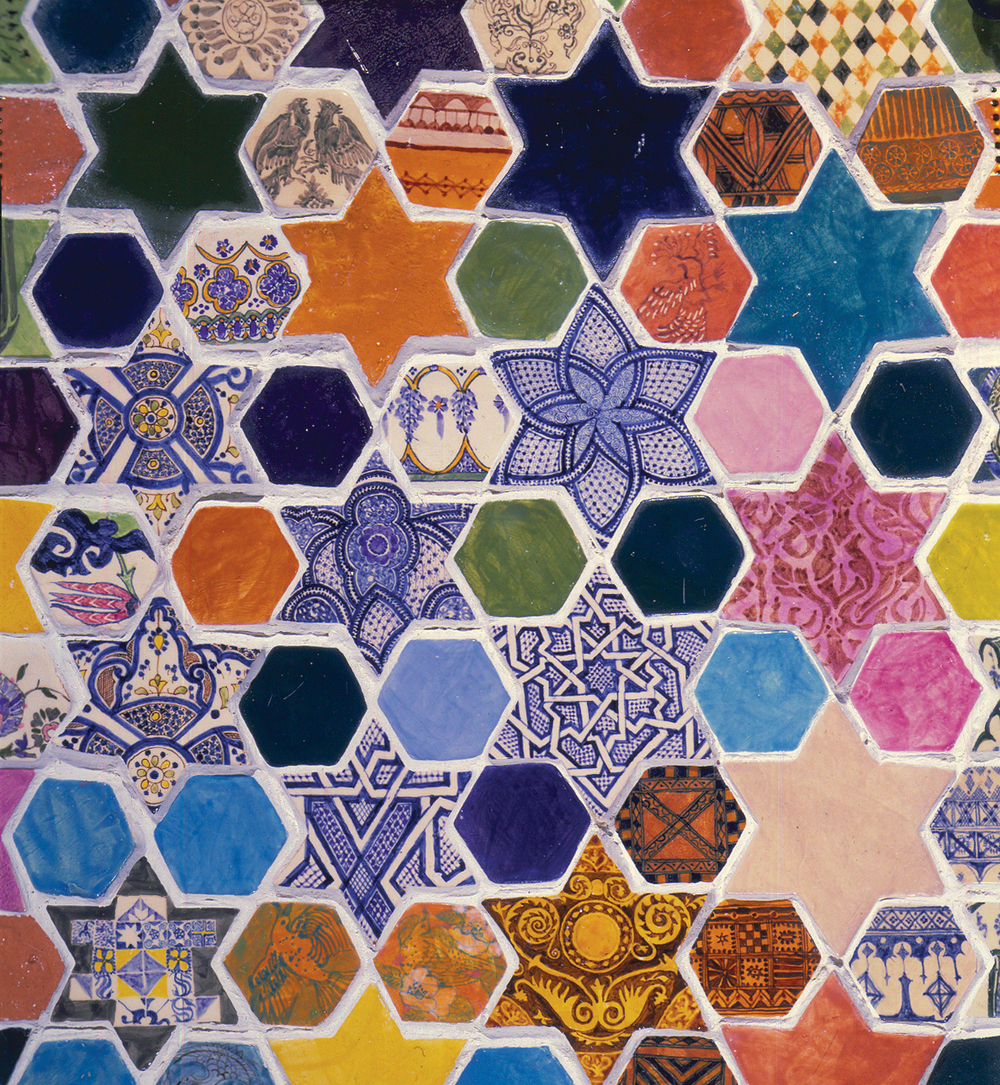

Made only a few years apart, Joyce Kozloff’s An Interior Decorated (1978–79) and Louise Lawler’s Pollock and Tureen (1984) exemplify the attitudes towards appropriation of P&D and Pictures respectively. Kozloff’s installation purposefully invokes a vast trove of non-Western textiles and ceramic traditions. Shown here installed at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, in 1980 FIG. 6 and at the Mint Museum, Charlotte NC, in 1980 FIG. 7it erupts as a lavish interior, adorned with fine silk hangings FIG. 8, tiled flooring FIG. 9 and paintings that generate a trompe l’œil effect, fostering an enlarged sense of space, for example in Striped Cathedral FIG. 10. Kozloff conjures the decorative splendour of the ancient non-Western palace complex, hand-painting thousands of tiles as a homage to anonymous artisan labour.

But this is not just an Orientalist fantasia. The appropriation is carefully systematised. Kozloff’s insistence on citation is a means of transparency, as she studied, managed and ultimately carefully attributes her sources for the silks, pilasters and the tile floor of the work itself within the essay she published in the exhibition catalogue:

I've painted motifs from many traditions onto these tiles: Native American pottery, Moroccan ceramics, Viennese Art Nouveau book ornaments, American quilts, Berber carpets, Caucasian kilims, Egyptian wall paintings, Iznik and Catalan tiles, Islamic calligraphy, Art Deco design, Sumerian and Romanesque carvings, Pennsylvania Dutch signs, Chinese painted porcelains, French lace patterns, Celtic illuminations, Turkish woven and brocaded silks, Seljuk brickwork, Persian miniatures and Coptic textiles. The motifs are clustered according to culture and when I made them, since I worked on the floor in sections. The entire piece is my personal anthology of the decorative arts.16

By combining decorative histories from multiple historic sources, Kozloff addresses the ‘anti-decoration bias’ that Perreault argued gave rise to the dominance of Minimalism and conceptualism during the 1960s and 1970s.17 In Fred Sandback’s yarn structures, for example, it is the ‘idea’ and ‘site’ of his work that is emphasised, rather than its (minor, secondary or feminine) materiality. As Sandback himself asserted, ‘The work is ‘about’ any number of things, but ‘being in a place’ would be right up there on the list’.18 Yet, as Kozloff’s installation so powerfully emphasises, cultural citation is a crucial link to site, and place and placemaking cannot be divorced from the sociocultural conventions, histories and traditions of making, highly dependent upon the specificity of cultural tradition as they evolved in a particular location. For instance, insofar as silk was a major economic commodity of fourteenth-century France, driving aesthetic innovation to its pinnacle, one hundred years from now we might also say that New York’s SoHo neighbourhood in the 1960s and 1970s was less about the art than about the architectonic: powerfully inscribed by a cultural milieu of studio construction, as artists across all artistic movements, regardless of individual artistic training, style or school, set about transforming commercial spaces into live/work artist lofts.19

Pattern and Decoration and Pictures, as well as their minimalist predecessors a decade prior, inhabited the same architectonic spaces. The self-renovated commercial loft, then, became the primary driver of post-1960s artistic production in New York, offering ideal space and lighting conditions in which to produce large-scale art, regardless of medium. That is, to the art historians of the future, it might be the neighbourhood, rather than the artists, that are the most important collective contribution.

While Pictures artists were strongly influenced by the preceding decades of Minimalism and conceptualism, their art was predicated on the deconstruction of signs and signifiers. Louise Lawler’s Pollock and Tureen FIG. 11 reframed the art object by presenting it within the domestic sphere of the American elite. Whereas Kozloff engaged the historical memory of pre-modern sources, Lawler chose a contemporary target at which to aim her critique of power. Lawler’s photograph shows Jackson Pollock’s Number 6 (1949) as it is displayed in the home of the Connecticut collectors Burton and Emily Hall Tremaine, where it functions as an instant signifier of wealth, taste, discretion and class.20 The composition, however, centres on an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century ceramic soup tureen, with only the bottom edge of Pollock’s painting visible, its slashing red and yellow a colour match to the tureen’s more delicate floral pattern.

Through her careful configuration, Lawler convincingly suggests that a high art object, even an abstract painting could indeed, in its domestic surroundings, be demoted to the realm of the decorative, despite any protest by Clement Greenberg to the contrary.21Lawler wins the argument: her forceful assertion discredits the critic’s masculinist legacy by countering it with a distinctly feminist (and lens-based) composition that pays homage to the decorative, and most particularly to the nineteenth-century history of women china painters, which was the subject of feminist reclamation at the time.22 Knowingly or not, Lawler makes good use of this proto-feminist history, the same sort of feat that Kozloff performs through her careful elucidation of decorative arts sources.

In Lawler’s photograph, painting is demoted to the decorative through its display: it serves as an ornamental flourish, adorning the blank wall space above a couch or a fireplace. Both Kozloff and Lawler, therefore, call upon the category of the decorative to signify a kind of otherness that is often interchangeable with a secondary or minor status. In this sense, the soup tureen is the foil: an object that brings clarity and finality to the consistent argument about the functionalism of all artistic objects, high art or not, as decorative baubles of the rich.

P&D artists, such as Kozloff, often engaged in a form of installation work that treated interior decoration as gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art. For instance, in his mixed media installation Furnishings at the Holly Solomon Gallery in 1977 FIG. 12, Kim MacConnel designed an entire living room, with chairs, sofa, window dressings, lamps and his own art, all painted in his signature cacophonous patterning, comprised of stripes, waves, polka dots and the like. P&D artists’ chosen investment in décor as a category to expand upon supersedes the single encounter that Lawler photographs. Yet Lawler’s celebrated work is still in danger of becoming what Perreault would have called ‘the photo-joke [that] still ends up over someone’s sofa’.23 Hers is a shorthand, meant to point out and then disrupt hierarchies of display in a single image. Conversely, MacConnel and his peers, such as Kushner and Tina Girouard, laid out a fresh vision for artist-inspired interior design, free from the convention of hiring design professionals who source particular furnishings as a means of highlighting luxury and taste. MacConnel’s installation, then, functions as a self-consciously elaborate room aware of its own artifice, as a means of critiquing not the interior design professional, per se, but rather, the designer’s wealthy clientele, who pay for the service of someone else’s good taste: electing to live with tastefully chosen objects while supressing their own desire for kitsch or comfort.

During the same winter of 1977–78, the New York-based collective Heresies, a group of women artists, critics and writers, published a thematic issue of their eponymous magazine subtitled ‘Women’s Traditional Arts: The Politics of Aesthetics’, which included numerous examples of texts written the previous year that formally, even eagerly, engage in what might be termed ‘educated primitivism’, that is, a well-intentioned, if problematic, attempt to integrate primary non-Western source materials into contemporary Western art production.

The article ‘Political fabrications: women’s textiles in 5 cultures’, written by a group of five women artists, each of whom contributed a short text about the weaving practices of five distinctive historic and indigenous communities: pre-Inca Andean (Peru), Maori (New Zealand), Chilkat (Oregon), Navajo (New Mexico) and early modern lacemakers (Western Europe). As they stated at the outset:

We came to our project curious, confused, angry, that even within the already denigrated category of ‘traditional art’, women’s objects had often been overlooked or misrepresented. We were ready to be sympathetic to the women whose objects had attracted us to this research in the first place. But we wanted to avoid merely replacing one set of distorted biases for another.24

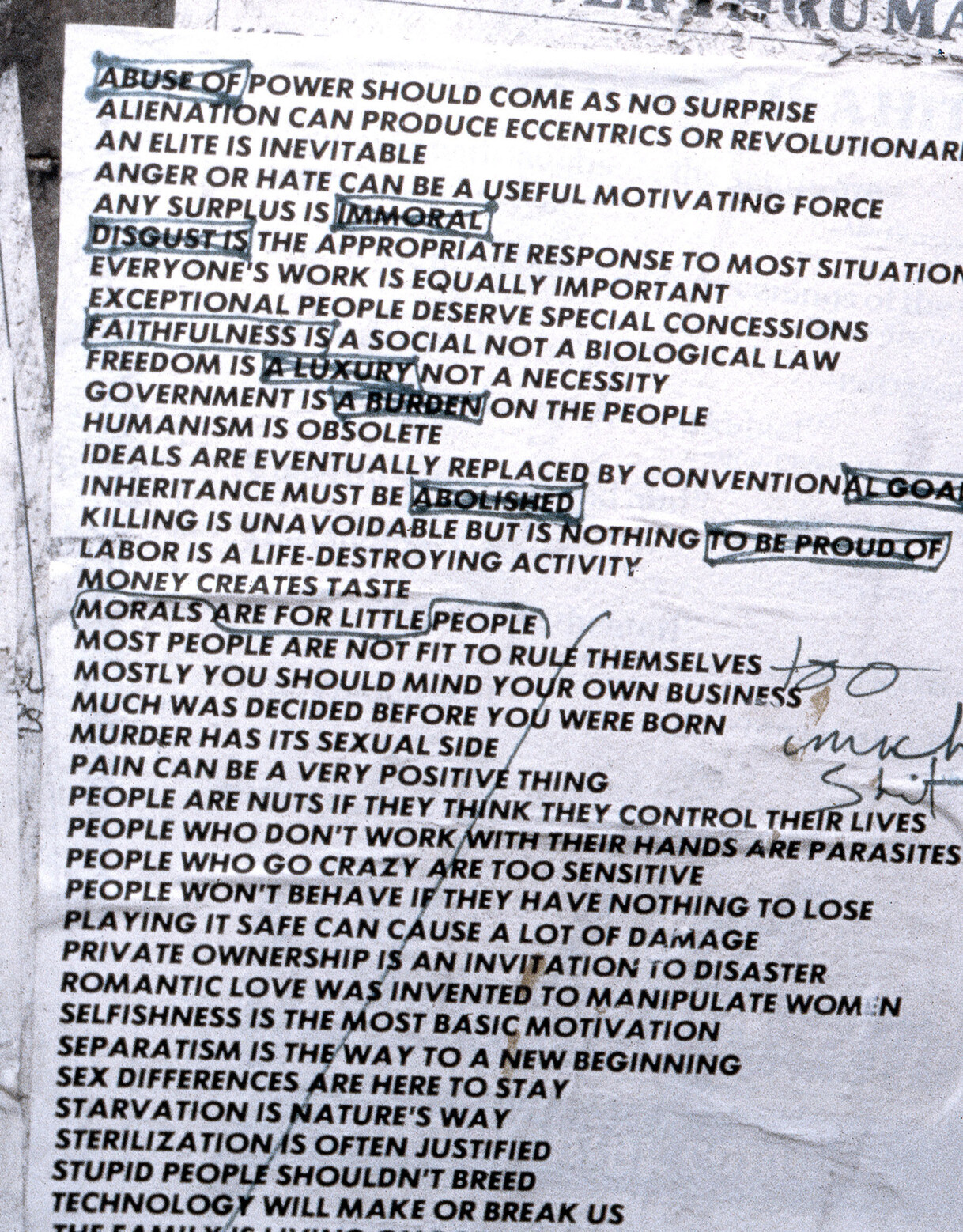

In approaching so-called traditional arts from the perspective of contemporary makers, the authors of the piece become mired in personalisation and empathy instead of attempting to fully comprehend the social contexts of the work as it was made, used and received. Rather than the intended ethnographic recovery, the artists end up hindered by their personal responses, which they recognised as untenable. But their tone – directly addressing their audience with honesty and self-awareness – is one of the attributes in common with the Pictures artists. The curator Johanna Burton describes this as ‘direct address’, which has long typified the works of artists associated with Pictures, such as Kruger, Rosler and Jenny Holzer.25 All three artists confront the viewer directly, using a variety of linguistic tactics that deliver a dose of humour or irony alongside an often caustic social observation, such as Holzer’s Truisms series (1978–87) FIG. 13.

Although their texts did not appear on the walls of galleries or museums, P&D artists were equally engaged in the use of irony and a textual-critical framework. In the aforementioned issue of Heresies, Jaudon and Kozloff published a now widely circulated article critiquing the masculinist language and biases against the decorative found in artists’ and art historians’ writings and manifestos. The article with its tongue-in-cheek title ‘Art hysterical notions of progress and culture’ assembles a wide-ranging list of quotations and groups them into categories, such as ‘Racism and Sexism’ and ‘Fear of Racial Contamination, Impotence and Decadence’, which directly showcase the ways in which the decorative arts have been historically denigrated.26 Categories such as ‘purity’, ‘humanism’ and ‘decorative’ contain running lists of quotations and statements of bias culled from artists, art historians and curators. Theirs was the first Anglophone artist community to excerpt Austrian architect Adolf Loos’s attack on the decorative in Ornament and Crime (1908).

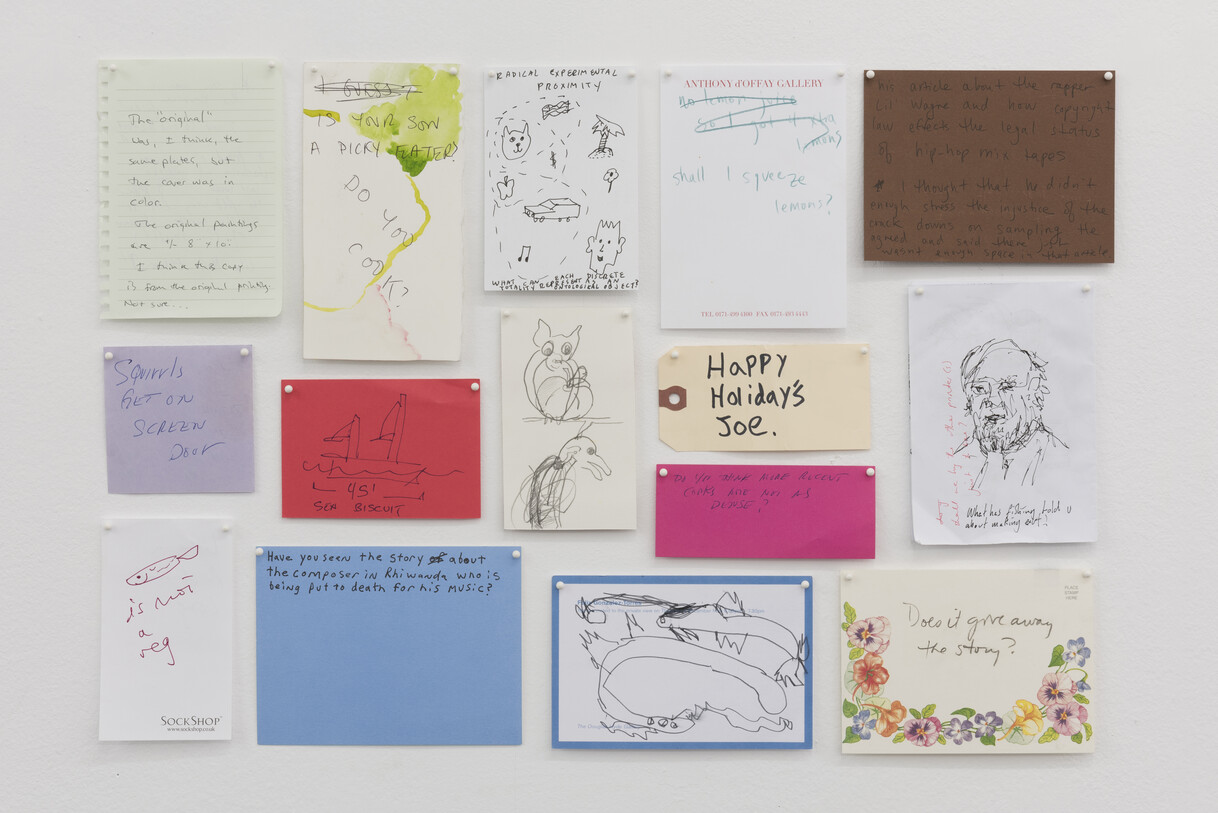

Such a provocative catalogue of quotations can be seen as a feminist predecessor to the intensive text-based collage works of artists such as Joseph Grigely and Sean Landers, who have made masculine failure a touchstone of their respective works. In a collage from 2017 FIG. 14, for example, Grigely creates a grid of coloured paper, scrawled handwriting, quick sketches and found images. Such a brightly coloured bricolage becomes a decorative compendium documenting the inner life of the artist.

Feminism and the critical apparatus

Feminism was at the epicentre of the Pattern and Decoration movement; associated artists were propelled forward by an engagement with the critical and art-historical works published at the same time as their artistic production. The artists – both women and men – of P&D were politically and theoretically engaged in feminist art-historical critique. That is, they were actively reading and reacting to the politics of display, gendered histories of representation and the flagrant absence of women artists in the traditional narrative of Western art, as highlighted by the art historians Carol Duncan and Linda Nochlin.27

Pattern and Decoration’s artists were propelled by the warm reception of critics such as Perreault, Amy Goldin, Jeff Perrone and Carrie Rickey.28 Goldin, in particular, served as an incisive force. She had been a student of Oleg Grabar, the leading Islamic scholar in the United States, and, in turn, Kushner and MacConnel were students of hers at University of California, San Diego between 1969 and 1971. In the spring of 1974, Goldin and Kushner embarked upon a three-month trip to Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey to explore Islamic visual culture.29 As Kushner wrote, in tribute:

She became an intellectual guide for both Kim and me, and later for the Decorative group at large. Kim and I would come up with an idea, and Amy would add to its scope and depth. She often directed us to arcane decorative subjects to investigate: New Guinea body decoration, Bed ruggs, court masques. Decoration expanded from the confines of kilims and flea market bad taste to embrace the world at large [. . .] She proposed criteria for ways to evaluate a decorative intention via formal elements.30

But one of the key differences in the content of the criticism was the level of rigour aimed at deciphering and analysing each movement. While P&D found champions within the ranks of the New York art press, Pictures garnered a particularly incisive art-historical elite, spearheaded by Crimp, which included Benjamin Buchloh, Rosalind Krauss and Craig Owens. Pictures created a substantial theoretical rhetoric that eschewed feminism in favour of a body of work on photography and its historical antecedents.31 Both movements lost a crucial interlocutor to untimely, early deaths: Goldin to cancer in 1978 and Owens to AIDS in 1990.

Ultimately, however, it was Pictures that spawned an entire œuvre of what today might be called the literature of postmodernism, beginning with Crimp’s ‘Pictures’ essay.32 This was followed in 1980 by Owens’s ‘The allegorical impulse: toward a theory of Postmodernism’, published in the spring and summer issues of October.33 In this two-part work, Owens links appropriation to allegory, and its strong roots in literature, in which appropriation enacts a kind of excess, or what he calls ‘a rhetorical ornament or flourish’.34 This is a fascinating conceit, especially in the light of P&D’s own tendencies towards the ornamental. For Owens, however, the relevant artists are those who produce art using extant or fully-formed images, for example, Brauntuch, Levine, Longo and Richard Prince. The reproduction itself becomes an allegorical supplement, or an extraneous construction that must be deciphered, digested and re-construed. Although Owens does not directly cite the allegorical as a Derridian supplement (that which is extraneous, extra, or beyond as a means of compensating for something lacking), this is assumed, as his articles essentially continue the conversation with a group of readers already in the know. In the previous year, Owens had published in October a translation of Derrida’s The Parergon (1979).35 ‘The allegorical impulse’ embodies Owens’s admirable ease in a trajectory of mainly French literary criticism, dependent upon a long parade of structural linguists (Louis Althusser, Etienne Balibar, Roman Jakobson), semioticians (Ferdinand de Saussure, Roland Barthes) and Continental philosophers (Benedetto Croce, Walter Benjamin), who are cited throughout the article’s dense text and accompanying footnotes.

The art historian Peter Muir writes of the inextricable link between Pictures and the rise of the journal October that, ‘The Pictures exhibition was successful in characterizing this new attitude in representation by the deployment of appropriated images, a deployment that further helped to ensure an artistic milieu that valorized the social significance of signs (semiotics)’.36 However, both movements were addressing entrenched media hierarchies: P&D was working through issues of high and low, while Pictures was an affront targeted at the dominance of painting, in particular, the rise of neo-Expressionist painting’s casual misogyny and commercial dominance.

In 1979 the New York critic Donald Kuspit published a vehement diatribe against Pattern and Decoration. He not only railed against the movement’s ‘superficial vitality’ and its ‘self-righteous heroism’, but framed his takedown in anti-feminist terms:

Feminist decorative art, more particularly but not exclusively pattern painting, is an example of feminist thought which has willingly emerged from its critical element, and as such signals the dawn of an era of authoritarian feminism, i.e. a feminism which means to entrench itself, to become as ‘corporate’ and establishment as the masculine ideology it presumably means to overthrow.37

Kuspit’s gleeful attack is a repudiation of the popularity and initial commercial success of P&D, as sold and marketed by Brooke Alexander, Holly Solomon and Willard Galleries. Over time, however, it was the Pictures artists who became the most critically and commercially acclaimed, beginning with the establishment in 1981 of Metro Pictures in New York, the dominant blue-chip gallery representing this generation of artists. Among others of the group, Holzer, Kruger, Prince and Sherman became museum mainstays in a permanently escalating art market.

Why was it that P&D faded while Pictures rose? Arguably, it was its clear feminist agenda that fell into disrepute, resulting in universalist essentialism as the 1980s wore on. Amelia Jones has reasoned along similar lines in her important re-examination of the politics surrounding Judy Chicago’s iconic sculpture The Dinner Party (1975–79), which also reworked decorative art histories through the use of china painting and needlepoint. Amelia Jones argues that the work itself ‘gave way to an examination of femininity as constructed through representation and a critique of the ‘male gaze’.38

In his attack Kuspit targets particular P&D artists (Miriam Schapiro and Kozloff) while fundamentally distorting the goals of the feminist art movement, insisting that the values of ‘transcendental femininity’ and ‘feminine sensibility’ (never, actually, the goals of either the radical or cultural feminist movements in the United States) had been replaced by a hard ‘authoritarian’ strain of feminism that he misconstrues as ‘an exaggeration of formalism [. . .] the pattern, uncritically used’.39 Cycling through various philosophical pronouncements (Adorno, Greenberg), he accuses the work of being ‘derivative’ and a version of Greenbergian ‘luxury painting’, a phrase which was originally a compliment to Matisse.40 Kuspit concludes this portion of his diatribe with a rather misogynist aside, squarely aimed at female biology: ‘It may be that feminist decorative art is also part of a decadent but fertile aftermath’.41

Kuspit’s critique fails to recognise that among P&D artists, pattern was not only critically employed, it was done so with intellectual verve and a communal sensibility that rejected the singularity of artistic genius as much as it sought to reinstate the historic importance of anonymously produced ornament to art and architectural history.

Rejection of authorship was a key impetus for both groups of artists. For Pictures this meant the embrace of the Duchampian readymade, as applied to a found image already out in the world, then slyly reworked to reconfigure or hijack the original meaning. P&D, on the other hand, explored the complex relationship between found ornamentation, world culture and the residual biases attached to the history of post-war painting. P&D asserted abstract painting’s decorative effects and feminine attributes, which had long been suppressed. It is a mistake to reduce the Pattern and Decoration movement to being simply playful and sensuous: it has never received due credit or critical acknowledgment for its rigour, the most consistently employed word used to describe Pictures. Time to borrow it back.

Acknowledgments

With deep appreciation to Lynne Cooke for her incisive remarks on this essay. Thank you also to Elissa Auther, Kayleigh Perkov and Gloria Sutton for being part of the cheering section at early moments in the drafts.